European Others

Against the background of an anxiety-ridden debate around threats to a European identity, Fatima El-Tayeb looks at how exclusionary spatio-temporal structures are being remixed throughout Europe to create a trans-local and trans-ethnic counter-discourse.

Being European without being white and Christian does not only put one in a strange place, but also in a strange temporality: Europeans who lack one or both of these qualities tend to be read as having just arrived or even as still being elsewhere – if not physically, then at least culturally. In European discourse (legally, culturally, socially, economically, academically…) the term “migrant” describes someone who moves across borders, but also includes all racialized European communities, which are reframed as non-European through their ascribed permanent status as migrating (from somewhere that is not Europe). This status is transmitted across generations and thus increasingly decoupled from the actual event of migration, shifting the meaning of “migrant” from a term indicating movement to one indicating a static, hereditary state. In other words, movement into Europeanness is impossible as long as racialised difference is still visible.

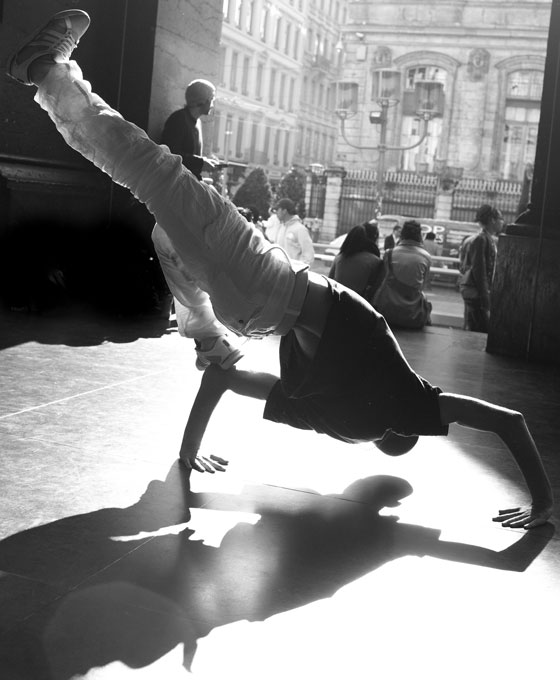

Photo: Simon. Source: Flickr

Racialized populations are thus positioned within a spatial and temporal paradox: they are permanently frozen in the moment of arrival – and the further away the actual moment/movement of migration, the stronger the paradox, i.e. the “queerness” of their presence in space and time. The current so-called third generation of post-war labour and post-colonial migrants is perceived to be more alien and out of place and time in Europe than their grandparents, the first generation of actual migrants, exactly because they are (made) impossible as an internal presence within (and by) the ideology of normalized colourblindness that places “race” and thus racialised populations necessarily outside of Europe.

While the European Union has been firmly established as a key political and economic player in the post-Cold War world, often appearing as the more humane, balanced alternative to militarized US domination (and as successfully having shed its imperialist past), the question of what exactly Europe is appears more unresolved than ever. Instead, there is an anxiety-ridden debate around threats to a European identity alternately defined as Christian, secular and Judeo-Christian and, at least implicitly, as white – as if uncertainty about Europe’s economic and political future could be ended by expelling those embodying “non-Europeanness”, that is, communities of colour – in particular black, Roma and Muslim.

At the same time, when working on racism and Europe, one is often faced with the assumption that such prejudice is non-existent on the continent – many white Europeans go as far as to claim that they “do not understand race”, usually when referencing a supposed US American obsession with it. Europeans tend to see the relevance given to race as one of the differences, if not the central difference, between Europe and the United States, and attempts to point to the important role of race (and racism) in European identity formations are frequently framed as enforcing an Americanised “political correctness” without meaningful European context.

Instead they are framed as an attempt at silencing necessary critiques of migrant communities and their supposed innate sexism, anti-Semitism, and homophobia (the prominence of discourses around “migrant extremism” notwithstanding, there is an equally prominent assumption that it is taboo to criticise these communities). And indeed, at first glance it might seem as if Europe exists outside of the US American (post)racial temporality. While the latter is built on a narrative of having successfully overcome intolerance and discrimination, the myth of European colourblindness claims that Europe never was “racial” (anti-Semitism is still often analysed as both an exception to this and as clearly separable from racism). That is, despite the origin of the concept of race in Europe and the explicitly race-based policies of both its fascist regimes and its colonial empires, the dominant assumption is that this history had no impact on the continent and its internal structures.

The repression of the long history of race and racism in Europe in turn produces the continent’s contemporary “multicultural” state (associated with visual markers of non-Europeanness, be it dark skin or a headscarf) as a novelty, which requires adjustment in the best case and resistance in the worst, and which, most importantly, can simply be declared to have “failed”. Multiculturalism in this sense does not merely describe a reality (which cannot be undone at will), but represents a particular discursive means to manage and control this reality through a narrative of linear global advancement that places Europe/the West as the inevitable hub of progress and human rights. This narrative produces the need and requires the ability to constantly rewrite history in order to re-centre Europe, resulting in the repression of colonial and (state) socialist legacies in the production of hegemonic discourses of history and memory in the contemporary moment.

This spatio-temporal regime of knowledge management configures racialized populations as displaced and anachronistic: they are perceived as being in transit, coming from elsewhere, momentarily here but without any roots in their “host nation”. Centring on the Enlightenment and the French Revolution but reaching back to the ancient Greek and Roman Empires, and forward to include the less celebratory realities of World War II, fascism and Stalinism, a linear narrative of Europeanness has been constructed and is used as foundation for an identity that transcends national divisions but remains firmly within internal limits.

Such a narrative requires a clear separation between what is European and what is not – an impossible task that invariably produces tensions that threaten the coherence of the construct. Historically, these tensions have centred on race and religion as markers of non-Europeanness. The temporal suspension of racialised communities, as here but not really belonging, also produces an out-of-placeness: due to their precarious position within Europe, communities of colour are defined through an excess of movement while simultaneously experiencing an extreme lack of it. Their discursive framing as eternal migrants, permanently stuck in a temporary condition, justifies and produces the material conditions of their exclusion, while preventing the acquisition of rights associated with long term presence, since it does not place them within the larger space/time of the nation. The embodiment of seemingly incompatible spaces and identities is the source of their erasure, but also the source of resistance.

In response to the specific forms of exclusion and marginalisation they face, second and third generations of migrants frequently draw on and transform modes of resistance and analysis originating outside of Europe and circulated in transnational discourses of diaspora, ranging from hip-hop culture to women of colour feminism. Exclusionary spatio-temporal structures are remixed into alternative models that allow us to think the unthinkable: an identity that is both European and non-white/Christian.

This remixing takes place in the art and activism produced by racialized Europeans, beginning in the early 1980s with the experimental work of the Black Audio Film Collective – maybe best expressed in John Akomfrah’s The Last Angel of History (1996), which brilliantly links Afrofuturism, a vision of the contemporaneity of past and future borne of the fundamental displacement of transatlantic slavery, the hybrid origins of hip-hop and Walter Benjamin’s claim that the tradition of the oppressed teaches us that the state of exception is the rule. This activistic remixing is continued by collectives like Kanak Attak, rejecting the logic that erases racialized Europeans between the binaries structuring progressive time and space – Orient/Occident, archaic/modern, rural/urban, fundamentalism/enlightenment, Islam/Europe, past/ future – by offensively embodying the unstable relationship between these supposed opposites; and of course remixing is everywhere in Euro hip-hop, negating the spatial logic of the state through a trans-local and trans-ethnic counter-discourse.

In Europe, the particular histories of colonialism, racism and migration create intersections and overlaps between, in particular, black, Muslim and Roma communities, which result in shared spaces (including the outer city, prisons and detention centres, inner city), cultures (such as hip-hop), histories, and positionalities (as not properly European). These connections are suppressed in dominant (policy-producing) discourses that assign each group a distinct representational function: Muslims appear as the internal threat posed by migration, the “other” that is already here but remains eternally foreign; whereas “Africans” (including black Europeans) represent the masses not yet there, pushing at the borders, the demographic (and racial) Goliath threatening to run over the European David (the prevalence of metaphors along these lines helps to normalize the extremely high death toll the EU migration regime produces on its external borders, complemented by a rapidly growing and increasingly privatised regime of mass incarceration of undocumented migrants). The Roma, finally, the quintessential European minority of colour, with a 500-year-old continental history that includes slavery and genocide, continue to face extreme violence, poverty and exclusion, while being completely absent as a recognized presence in contemporary Europe. Instead, they are framed as not only coming from another, non-European, space, but also from another time, an idealized European past, as reflected in the centrality of “gypsies” in continental folklore.

The discursive separation of these groups is symptomatic for the ways in which de facto intersections of communities of colour – with each other and with white Europe – are negated within the ideology of colourblindness, which cannot allow for porous boundaries and instead has to continuously produce distinct and homogenous communities. The particular forms of exclusion produced by this system require methods of resistance that cannot always be direct, and instead have to use detours, disidentifications, and diversions in order to produce positionalities from which to break the silence around Europe’s deeply racialized sense of self. This strategy of “queering” ethnicity, practised across the continent by multi-ethnic hip-hop crews, black and Muslim feminists, queer performers, urban guerrilla video artists and many others, is grounded in the shared, peculiar experience of embodying an identity that is declared impossible, even though it is lived by millions, the experience of constantly being defined as foreign to everything one is most familiar with.

This article was first published in the book Remixing Europe: Unveiling the Imagery of Migrants in European Media (2014), a Doc Next Network publication produced in the framework of Remapping Europe, A Remix Project Highlighting the Migrant’s Perspective. This investigative and artistic project explores the tools and concepts of remixing media as a method to re-view, re-investigate and re-consider prevailing imageries of migrants in European societies.

Published 22 February 2017

Original in English

First published by Thomas Roueché / Doc Next Network, eds., Remixing Europe (ECF / Doc Next Network, 2014)

© Fatima El-Tayeb / Doc Next Network / ECF / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTIn collaboration with

In focal points

Newsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Related Articles

A European elephant in the room

On public space, ecology and the lands of Europe: a conversation with Tim Flannery

Europe has never been a place for racial or environmental purity. Situated at a crossroads of the world, it has always been characterized by change and hybridisation. Palaeontologist Tim Flannery calls for reinventing the commons and bringing elephants back to Europe.

Once referring to natural resources and collectively managed land, the notion of the ‘commons’ has expanded across cultural, scientific and digital realms. Can commonality dodge the threat of capitalist exploitation and develop into an organizational principle for complex societies?