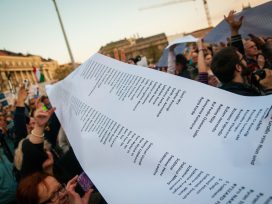

Myths of shock therapy

Philipp Ther talks neoliberalism’s toll on the peripheries

After ’89, the ideology of ‘free’ markets prevailed not just in eastern Europe, but also in the West. The consequences were particularly evident in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis and the 2010 euro crisis. What effect did the economic restructuring have on the European project and what are the key issues facing Europe today?