Osteuropa: Your daughter was one of the thousands of people detained by the Lukashenka regime in the past ten days. How did you find out? Do you know the reason for her arrest and where she is being held?

Artur Klinaŭ: It was on the day before the elections, 8 August, that I learned of my daughter’s arrest four days previously. She had been acting as an observer at one of the polling stations and was keeping count of the number of voters who turned up to vote during the early voting period preceding the day of the election proper. It is the regular practice of the official electoral commissions to inflate this number, so the presence of independent observers was highly undesired.

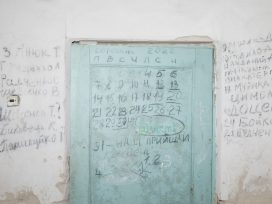

Marta was arrested on a trumped-up charge of using foul language, hindering the work of the polling station, and resisting officers of the militia – all standard accusations brought against any unwelcome opponent of the regime. For three days we had no idea about where she was being held. Then there was a trial, at which she was sentenced to fourteen days imprisonment, then two more days of being kept in the dark about where she was being taken. But we know now for certain that she is in prison in the town of Zhodino, to the east of Minsk. The number of people arrested has been so large, that the courts and prison service are unable to cope; they frequently cannot say who is being held and where.

Who are those who have now come out to protest on to the streets?

Previously it was only an active minority who protested, but now it is the nation as a whole. The mood of protest has spread quite literally to all sectors of the population. Of course, the slogan ‘Sasha 3%’ was thought up for the election. Independent surveys put Lukashenka’s rating at about 30% but, following the brutal suppression of the peaceful protests, it has undoubtedly fallen further – quite conceivably to 3%. We can now say with absolute certainty that the overwhelming majority of the population opposes Lukashenka. Support for him now comes from groups that have something to lose: the state officials and businesspeople whose social status and wealth have grown during his regime, the law enforcement agencies, the judges and other officials who have connived with him in repressions and falsifications.

Who are the OMON (Special Purpose Police Brigades)?

The OMON consists mainly of lads from the provinces. The regime provides them with the opportunity to get on in the world. Ideology has nothing to do with it. In all the years of his rule, Lukashenka never got around to formulating a clear set of principles. Loyalty is more likely to be for material gain: high salaries, privileges, flats in Minsk, early pensions. And of course, there is the fact that many of them have been heavily involved in the repressions. For them there is no way back.

Protest rally, Minsk, 16 August 2020. Photo by Homoatrox / CC BY-SA from Wikimedia Commons

Are there any obvious leaders of the protest movement? Or is it self-organising?

The protest movement does not as yet have a clear leader. Tsikhanouskaya was afraid to take upon herself the responsibility for people protesting on the street. At a purely human level this is understandable. Whoever heads a revolution takes upon themselves the responsibility for the consequences. However, for her as a politician this was a weak move.

But she was obviously threatened and forced to leave the country.

Of course, massive pressure was exerted on her, and it broke her. However, the fact that her absence from the scene – and that of the campaign teams of all three opposition candidates – in no way affected the growth of the protest movement proves that the votes in the election were cast in the election not so much for Tsikhanouskaya, as against Lukashenko. She is now trying to get back into the game, but the ‘Joan of Arc’ image she had prior to the election has been dealt a serious blow. That may all be forgiven; people love a populist. If the revolution is indeed victorious, I think that the most likely outcome will be new elections run in a properly democratic fashion. It is now legally impossible to declare Tsikhanouskaya the winner of the election on 9 August, as all the original documents have probably been destroyed.

You belong to the middle generation. That means that you took part in the protests of 2010. How does the situation now differ from the situation back then?

There is one radical difference and one radical similarity. The similarity is that the key player on both occasions has been the Kremlin. In 2010 it arranged things so well that for many years Lukashenka found himself cornered: the EU introduced sanctions, the gradual process of democratisation was stopped, and so on. The next step was supposed to have been the surrender of sovereignty. But then war began in Ukraine, the geopolitical situation changed, and Lukashenka had a chance to extricate himself from the Kremlin’s stranglehold.

This time, the Kremlin put as much pressure on Lukashenka as possible. There are indications that the Kremlin – or rather structures connected to the Kremlin – was the ultimate sponsor of the opposition campaign. No election campaign in the history of independent Belarus has been conducted in such a professional, smooth manner. It gave the impression of having solid backing and of being run by experienced campaign managers. The West distanced itself from the opposition and offered no support, either financially or otherwise.

These and other factors make it highly likely that the secret beneficiary of the campaign was indeed intended to have been the Kremlin. However, the aim was not to replace Lukashenka, but to repeat 2010: to provoke repressions, so that the West would break off dialogue and reintroduce sanctions. In other words, to again drive Lukashenko into a corner. What Putin needs is a weakened and tractable Lukashenko who is be prepared to hand over his country to the Kremlin in some form of hybrid annexation.

In principle, the plan worked well. The blockheads in Minsk played their parts, and even tried too hard. But right then a third player appeared on the stage – the Belarusian people – and events begin to depart from the script. This is the point where the situation today differs radically. Society has been angered by what has been happening over the previous six months: Lukashenka’s attitude to the coronavirus pandemic and the economic decline. Then came the disastrous mistakes the authorities made in the elections. Their claim that 41% of the electorate had voted early and that Lukashenko had won 80% led people to realise that they were being duped. Protests were then met with the previously unseen levels of violence in the days that followed. Society exploded with a desire for change. Everything now depends on the courage and strength of the Belarusian people to stand firm for their own interests, rather than the interests of scriptwriters in Minsk and Moscow.

How has the situation changed for writers, artists and musicians over the past five years?

From the political point of view there is greater freedom. Economically, however, independent Belarusian culture has been fighting for survival. Belarus has been overlooked internationally, and consequently many grant-giving foundations have withdrawn from the country. Finding funds for independent cultural activities has become increasingly difficult. It continues to be pointless to hope for support from the state, and so Belarusian culture has had to learn how to earn money for itself. This has not always been successful, and a significant number of important cultural projects have been forced to close.

However, the idea of private patronage of the arts has begun to emerge. The strongest developments have been in areas of culture that attract private capital. In recent years, the most interesting patron of Belarusian culture has been Viktor Babaryko, who had been planning to run as an opposition candidate until his arrest and imprisonment. Belgazprombank, the bank of which he was chairman, sponsored several major projects, for example the festival of theatre ‘The-art’, the gallery OK-16, and the ‘Paris School’ collection. The financial for writers using Belarusian has not improved. Print runs for books in Belarusian have grown, without this having an impact on the material position of their authors.

What role do Lithuania and Poland play as places of permanent emigration or temporary residence for members of the intelligentsia and individuals active in various areas of culture?

The support of our neighbours and, of course, Germany has been very important for us in recent years; they have been the first to show their solidarity with the democratic struggle of the Belarusian people. It is of vital importance that Europe stands with Belarus at the present time, in order to avert the hybrid annexation of the country.

Is there a chance that Lukashenko will lose the support of the law enforcement agencies?

This is already happening. Cracks are beginning to appear in the regime. Even if the revolution does not succeed, society will not be able to return its previous state. Change will come in the very near future!

Interview with Volker Weichsel, originally published in German on 14 August 2020