Ukraine faces its greatest diplomatic challenge yet, as the Trump administration succumbs to disinformation and blames them for the Russian aggression. How can they navigate the storm?

Of course radical nationalists do not share the original goal of the Euromaiden protests: bringing Ukraine closer to the EU. But neither do their slogans and attacks invalidate the protests’ value as a manifestation of the democratic aspirations of the Ukrainian people, writes Volodymyr Kulyk.

In his article published in Eurozine on 10 January, leftist Ukrainian sociologist Volodymyr Ishchenko harshly criticizes the open letter by prominent European academics in support of the Ukrainian anti-government protests known as Euromaidan. He rightly argues that “the letter shows an unacceptable level of simplification and misrepresentation of the very contradictory nature of the Ukrainian protests”. Unfortunately, his own text is no less of a misrepresentation.

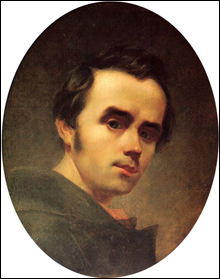

Taras Shevchenko, Self-portrait, oil 1840. Source:Wikipedia

That the western academics presented a less than nuanced picture of the Euromaidan protests is regrettable but understandable. After all, this is how events in Ukraine and other non-western countries are usually perceived and represented in the West, even among academics not specializing in these particular countries. Moreover, given that the letter was written with the intention of reaching a wide, non-academic audience, one could hardly expect the authors to make fine distinctions between the different ingredients that have gone into the making of the current Ukrainian protests. However, writing about his own country for the mostly intellectual audience of Eurozine, Ishchenko could have presented a balanced and nuanced picture of the protests, rather than bluntly discrediting certain elements that do not fit his ideological preferences.

In his blinding opposition to both nationalism and capitalism, Ishchenko lumps together two very different matters: the role of rightwing radicals in Euromaidan and the role of these protests in Ukraine’s choice of future. He is right that the radical nationalists do not share the protests’ original goal of bringing Ukraine closer to the European Union and harm the democratic movement with their divisive slogans and their attacks on ideological opponents within the movement. However, he is wrong in arguing that such slogans and attacks invalidate the protests’ value as a manifestation of the democratic and European aspirations of the Ukrainian people.

Although radical nationalists such as the Svoboda (Freedom) party and the less well-known organization called Rightwing Sector do not by any means constitute the majority of protesters, they are indeed rather prominent due to their vocal and visually striking behaviour. Many prominent figures in Euromaidan criticized these elements’ partisan actions, particularly the torch-lit march in Kyiv that Svoboda organized on 1 January to celebrate the anniversary of the nationalist leader Stepan Bandera. Another obviously divisive initiative of Svoboda, the posting of Bandera’s portrait at the main entrance to the building of the Kyiv city administration, which the protesters had seized in early December, was met with such indignation that within hours, Bandera gave way to the unifying figure of the national bard Taras Shevchenko. Unfortunately, several attacks by Svoboda activists on their ideological opponents, although denounced by the groups that were targeted, remained little known and thus unopposed among the larger masses of protesters; all the more so because of the prevailing spirit of maintaining the unity of the movement in its confrontation with the repressive regime.

This spirit also accounts for a lack of resolute opposition against Svoboda’s attempts to impose on the democratic pro-European movement some slogans of the underground Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN) that waged the terrorist war against the Polish, German and Soviet occupiers in the 1930s and 1940s. However, the reception of these slogans and their underlying values has been far from enthusiastic. Although few speakers denounced the inappropriateness of these slogans from the podium on the Maidan, only a minority of protesters has actually responded to them. The only exception is the nearly universal appropriation of the most famous pair of slogans, “Glory to Ukraine! Glory to heroes!” This, however, should not imply the acceptance of its old, exclusively nationalist pathos, since most people responding to the slogan certainly mean not the heroes of the OUN terrorist activities but rather all the heroes of the centuries-long Ukrainian struggle for independence and a dignified life, up to and including the current struggle on the Maidan. It is hardly surprising that in times of ordeal, people seek inspiration in heroic forerunners. Although such expansion of the pantheon may be unacceptable for many Ukrainian citizens, particularly in the east and south, it is by no means appropriate to continue limiting the pantheon to those figures approved by Soviet propaganda.

Most importantly, the harm done by radical nationalists’ partisan activities to the broad protest movement by no means devaluates the movement as a whole. In his attempt to discredit it, Ishchenko grossly misrepresents the protests’ social base and ideological orientation. It is simply not true that Euromaidan is a protest of western and central Ukraine and overwhelmingly opposed by residents of the east and south who are afraid of the economic and social consequences of the Association Agreement with the EU, were it to be signed. While the initial wave of protests was indeed evoked by the Ukrainian government’s unexpected refusal to sign the agreement, it was only after the brutal dispersion of this meagre protest that a large-scale, geographically and socially inclusive movement emerged whose main concern is not the Association Agreement or Ukraine’s European integration more generally but radical democratic changes in the country.

To be sure, the movement primarily consists of and is supported by residents of the west and centre but, as the leading Ukrainian sociologist Iryna Bekeshkina recently argued, even in the east and south at least as many people participate in the Maidan as in the pro-government anti-Maidan. Moreover, while anti-government protesters participate willingly and with great sacrifice, those demonstrating in support of the government are mostly paid and/or forced to do so. Last but not least, slogans prevalent at the anti-Maidan refute Ishchenko’s thesis that the easterners’ opposition to the Euromaidan protests is primarily driven by concern for the economic consequences of the Association Agreement. Rather than protesting about loss of jobs in the event of the agreement being signed, they denounced the so-called Euro-Sodom and distance themselves from any actions and wishes of the “Banderites”, which in their parlance pertains to all westerners. In other words, their opposition to the Maidan has to do not with economic considerations but with an identity dilemma: for them, European integration means a betrayal of the East Slavic unity, all the more so because the former is advanced by champions of a Ukraine clearly distinct and distant from Russia. Perhaps the most important lesson of the current protest is that this dilemma, while still important for many Ukrainians, cannot prevail over unified opposition to a repressive regime that treats people like dirt.

As I write the above paragraphs (which took me four days due to my preoccupations with activities on the Maidan), the escalation of protests brought more evidence of my arguments. Since the beginning of violent clashes between radical protesters and the riot police (to which the former resorted in a desperate response to the recent flagrant curtailment of democratic liberties), the leadership of Svoboda has been greatly discredited among protesters owing to its perceived cowardice in the face of an emerging war. Understandably, many protesters considered this a much graver sin than the inadequate nationalist slogans or torch-lit marches. At the same time, as the weak Euromaidans in the eastern and southern cities came under attack of thugs instigated by the authorities, groups of ultras of the local football clubs started defending the protesters – incidentally, under the same slogans: “Glory to Ukraine! Glory to heroes!” While some foreign commentators raise the spectre of a civil war, every day I read my Facebook friends’ objections that this is a war not between various elements among the people but rather between the fearless people and a degenerate regime.

Whatever the outcome of this war, Ukraine will never be the same.

Published 24 January 2014

Original in English

First published by Eurozine

© Volodymyr Kulyk / Krytyka / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTSubscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Ukraine faces its greatest diplomatic challenge yet, as the Trump administration succumbs to disinformation and blames them for the Russian aggression. How can they navigate the storm?

Why does peace in Ukraine hang on a ‘mineral deal’ whose handling is more reminiscent of trade than negotiations? Perhaps because the global race for critical raw material mining is well and truly underway, digging for today’s equivalent of gold: raw earth elements and lithium critical for renewables and digital technology but also modern weaponry.