Divided in the Anthropocene

Unlike the political challenges and wars of the past, the climate and environmental crisis we now face is universal. Yet green movements remain on the political periphery and continue to be viewed in narrow, reductionist terms. What kind of solidarity can unite the emerging ecological class?

In 2022, the French philosopher Bruno Latour and the Danish sociologist Nikolaj Schultz wrote a small book together, a ‘memo’ entitled On the Emergence of an Ecological Class. There, they pose questions that will be relevant, crucial even, for years and decades to come: ‘Under what conditions can ecology organize politics around itself rather than being one group of movements among others?’ Can ecology (and, within that, the climate crisis) become the basis for a new framework of politics and define the whole political field, rather than being just another struggle that seems to multiply infinitely?

The gravity of the climatic and environmental predicament we face suggests that our immediate answer should be yes – climate change and the environmental crisis are such all-encompassing existential threats that there is no way they will not reframe our politics anew. So why is contemporary realpolitik still so far from arriving at such a place?

Part of the reason is the absence of a proper ‘green’ political subjectivity. Latour and Schultz argue that a distinctive ecological class – one with its own specific solidarity, which could serve as a social bond linking all the various peoples around the globe in a common interest and struggle – is still in the process of forming. At the level of parliamentary politics, electoral support for green parties – which should, in theory, serve as a representative body of such a class – is unstable or has made only minor gains. Instead of reframing the whole political field, green concerns are being assimilated into the standard political agenda as just another issue among many.

Yet it is already clear that such an ecological class cannot be a class in any traditional sense: it has no specific socio-economic base. While environmental concerns are sometimes associated with the ‘post-material’ values embraced by the wealthy middle classes from the Global North, nothing could be further from the truth than the assumption that environmental and climate struggles are something post-material. If anything, they belong to the sphere of materiality that precedes any of our ‘material’, economic interests: they represent the very conditions of prosperity, as there is no economy on a dead planet.

Environmentalism as a new universalism

The climate and environmental crisis is universal: neither local nor global, it exists on all scales as omnipresent. There is no safe space, no haven that could protect anyone from its impacts. Contrary to what some voices express vis-à-vis climate justice, I think it is rather counterproductive and ultimately false to add to the delusion that rich and privileged people can somehow shield themselves from the impacts of climate disaster and the subsequent collapse of ecosystems.

The luxurious underground bunkers in Hawaii or New Zealand that are being advertised by their owners as protection from societal collapse are nothing more than an emerging market of doomsday insurance companies exploiting and capitalizing on the existential fears of the super-rich. In an atmosphere of ‘generalized climate anxiety disorder’, the insurance business may be flourishing, but its offers, say, nothing about the potential impacts of the eco-climate crisis. It only shows that some people are desperately willing to believe that they can survive and thrive deep underground on some isolated island.

The various intensity of the current effects of this crisis in different parts of the world – especially in the Global South – should not blind us to its universality. Its scale is planetary and in the long run, no one can hide from it. The good news is that within this universality lies a chance for truly inclusive solidarity within the emerging ecological class. Although this class is – in theory – a vast majority, in practice it is still rather marginal and weak, as it lacks a shared class consciousness and identity. This vacuum makes it vulnerable to appropriation by various other struggles.

Within wider climate-related discourse and activism, we often see how various emancipatory identities try to subsume the eco-climate crisis within their own particular conceptual framework. Thus, for example, when seeking to understand the roots of our current predicament, the environmental and climate crisis is seen by some strands of feminism as caused by a patriarchal system, by colonialism (according to decolonization theory), or rooted in a metabolic rift between capitalism and nature by eco-Marxist thought.

However, rather than environmental and climate causes becoming assimilated in identity politics (although this seems to be happening already), the ecological class can potentially include all kinds of emancipatory struggles within its universal imperative to maintain the habitability of our shared planet. Any emancipatory struggle is ultimately futile without tackling the common ground — the web of life that serves as the condition for our continued existence. This is also an opportunity to break out of the unproductive deadlock of culture wars. But for that to happen, the ecological class needs to establish itself by identifying a specific social link between its members. To ask the old question anew: what kind of solidarity can unite the emerging ecological class?

What solidarity is (not)

But what is solidarity in the first place? The classical definition comes from the French sociologist Émile Durkheim, who differentiated between mechanical solidarity (based on kinship, similarity and identity) and organic solidarity, based on an understanding of mutual interdependence. Either way, solidarity is not random but an essential component of any political, collective subject – be it a nation, a citizen-based demos, a working-class proletariat, or any of the new emancipatory identities based on gender, ethnicity, culture or religion.

Solidarity supposes a certain sense of unity, a common ground, alongside an ability and willingness to empathize with the other, who is not just the other but an inhabitant of a shared (symbolic) space. It is an underlying social bond that is invisible in everyday life and can temporarily manifest itself more visibly during emergencies. ‘We’re all in this together’ especially applies when we are faced with a common threat – when our existence is in peril, we all of a sudden realize the unifying effect of danger.

In his three-part opus magnum Spheres, the German philosopher Peter Sloterdijk provides a topological definition of solidarity: a social bond between those who cohabit in a shared world. In this concept, solidarity is originally an intimate sphere of socio-psychological warmth that insulates its members from the coldness outside. While easy to maintain in small groups of hunters and gatherers, with social expansion and the creation of large clans, kingdoms, or modern nation-states and their supranational constructions, the social bond needs to be maintained through the ‘artificial intimacy’ provided by shared cosmologies, religions, ideologies or by ‘shared values’ – the creation of a common symbolical world-sphere.

In the case of climate change, this is not even metaphorical: today, our common planetary atmo-sphere, insulating us from the freezing void beyond, is crumbling. Due to human activity, it is undergoing a profound change that threatens the very conditions of planetary habitability. However, as with intimate relationships, maintaining long-distance planetary solidarity looks like an unsurmountable task. The larger the political body, the more alienation and potential for division arise. Raising a planetary awareness – the notion of Mother Earth (or spaceship Earth, according to the American architect Buckminster Fuller) as a shared home – may prove to be an immense challenge that cannot serve as common ground for any ecological class. Common planetarity is still rather an abstract and impersonal concept, one that is incapable of spurring large-scale, collective action.

(Eco)solidarity of the shaken

3D globe. Image by Thomas Amberg via Wikimedia Commons

But is it possible to create a universal solidarity that does not require being rooted in common ground? We find a perhaps surprising answer in the work of the Czech philosopher Jan Patočka. In his Heretical Essays in the Philosophy of History, he developed an alternative concept of solidarity: the ‘solidarity of the shaken’. At the heart of this concept lies a paradox: while the usual solidarity is based on common ground, according to Patočka, the solidarity of the shaken stems from the experience of the complete loss of ground, an existential groundlessness caused by frontline experience. Such ‘shaken-ness’ destroys old meaning in order to make a space for the creation of a new one. Patočka is convinced that only the destruction of all false, socially given meanings can lead to a new, authentic meaning.

The solidarity of the shaken thus does not arise from shared identity, ideology, or territory. Instead, it finds its origins in experience. Inspired by the writings of Ernst Jünger and Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, Patočka thought that the frontline experience from World War I could constitute a unique social bond among those affected, a solidarity between people who have been shaken by unspeakable things, a solidarity of survivors. Like others among his contemporaries, Patočka sought to create a concept of social bond that would evade any Identitarian, reactionary or nationalist form. From grounding themselves in groundlessness, human beings could create a community of those ‘who are capable of understanding what life and death are all about and what history is about’.

The frontline experience therefore had the potential to be an event that could change both the course of individual life and history itself. As such, it could become a breakthrough: an emancipation from a past that was about to destroy the future. Frontline experience is not a mere trauma but a radical, fundamental transformation through which one overcomes mere individual interest and opens up to greater meaning.

According to Jünger, who experienced World War I first-hand, the initial absurdity and unbearable horror of war gradually transformed into a new, overwhelming meaning for an individual. Patočka claims that this is also true on a large scale. In the fifth of his Heretical Essays, he says: ‘History is nothing other than the shaken certitude of pre-given meaning’. In the sixth essay, he makes the claim that ‘The First World War is the decisive event in the history of the twentieth century. It determined its entire character’. Out of absurdity and horror, a new era was forged.

However, I would argue, the experience of being shaken to the core is not exclusive to war. The most thorough description of an analogy between being shaken by war and being shaken by the climate crisis can be found in the American writer Roy Scranton’s book We’re Doomed. Now What? Essays on War and Climate Change. Scranton, who served as a soldier in Iraq, connects the dots between war and climate: the extreme experience of both, if allowed, can create a new meaning: ‘Accepting the fatality of our situation isn’t nihilism, but rather the necessary first step in forging a new way of life. … We owe it to the generations whose futures we have burned and wasted to build a bridge, to be a bridge, to connect the diverse human traditions of meaning-making in our past to those survivors, the children of the Anthropocene, who will build a new world among our ruins’.

Scientists, researchers, activists, environmental militants, farmers… An increasing number of people have been forced to feel the direct impact of climate change and environmental destruction on their lives. Being on the frontlines of the climate crisis, those in the Global South are especially vulnerable – though with climate change now having entered its universal stage, it is almost impossible to find a person on the planet who has not been affected by it in one way or another.

The environmental and climate crises have become personal and existential – when the very existence of humanity is at stake, the meaning of ‘existentialism’ undergoes a profound change. While the ‘classical’ humanistic (and human-centric) existentialism arises from confrontation with individual finitude – the fact of the mortality of the self – the potential for new, eco-centric existentialism arises from confrontation with the possibility of collective finitude – not just the death of individuals but the death of all their context. The very framework of individual lives is at stake. This environmental shaken-ness means an insight into the end of life itself, which can serve as an existential breakthrough, a revaluation of all values.

In our time, such environmental metanoia – a radical change in one’s life based on the experience of virtually losing the ground under our feet – stems from an awareness of life and death on a large scale. It becomes a shared experience of loss, after which we find ourselves unable to live our lives the same way as before. And that is an unmistakable sign: if no change has occurred in our lives after we have confronted the climatic and environmental predicament facing us, we still don’t understand the magnitude and gravity of what is really happening.

Therefore, to become a part of the ecological class is an invitation to a space shared by those whose perspective has radically changed. From there, the world looks different: what has hitherto been a guarantee of purpose in our everyday lives suddenly looks devoid of any meaning. For the ecological class to emerge, people need to allow themselves to be shaken, without any disavowal, while facing what is truly happening with nature, with life on this planet, with what is the most important.

Inevitably, the solidarity of the shaken is a rupture with the social order. All normality is suddenly seen as madness; what has been considered healthy is sickening. Rooted in collectively shared shaken-ness, it offers an opportunity to be unified by a common purpose that transcends mere individual interest.

The politics of the shaken

The environmental and climate crisis is a political truth of our time, around which a new political subjectivity can and must be formed. The emerging ecological class has the potential to bring with itself a new kind of politics, rooted in a new social bond from which a different political order can arise. None of this is a mere ethical or moral imperative – rather, it is practically understood as something that simply needs to happen, for the situation demands it. Nothing less lies ahead of the ecological class than to reinvent history and give it a new sense: to become nature defending itself.

In modern societies, it has become normalized to understand solidarity between people as an ethical imperative or moral duty. However, it is neither. The moralist concept of solidarity is rather the spontaneous ideology of a highly atomized society living under the delusion of individual self-reliance. All ethical imperatives and moral duties then feel like something extra – additions to lives driven by self-interest that from time to time feel like adding some warmth of moral sentiment to their otherwise cold-hearted mindset. In such a social arrangement, solidarity is something secondary at best.

Rather than the moralism of atomized individuals in a futile attempt to create an archipelago from isolated islands, a symbiotic interdependence is needed: a new social contract that will overcome the old idols of reckless profit-seeking and extractivism. The solidarity of the shaken is not a mere moral sentiment. Stemming from the radical experience of an uprooting groundlessness, it seeks to take root in the Earth again. For this to happen, the ecological class needs to develop and spread a new form of eco-rationality and eco-interest that will overcome the narrow interest of contemporary homo economicus.

In their memo, Latour and Schulz are not afraid to claim that for that to happen, the ecological class needs to occupy the state apparatus on all levels and in all its functions in order to repurpose it for its new role: to ensure the habitability of its territory and the planet as a whole. Whether the ecological class ultimately succeeds in such a historical task depends on how deeply people allow themselves and their old certainties to be shaken by the crisis. No real social change has ever been possible through moral sentiments and goodwill alone. Instead, a shift in the direction of history can arise from a shared, collective experience of threat and danger that forces us to act. The climate and environmental crisis is not a moral issue – it is an existential threat. Any denial or disavowal is therefore lethal for the future, as is social inertia – the worst enemy of any meaningful change.

Published 11 November 2024

Original in English

First published by Eurozine

Contributed by Institute for Human Sciences (IWM) © Martin Vrba / Institute for Human Sciences (IWM) / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTIn collaboration with

Newsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Related Articles

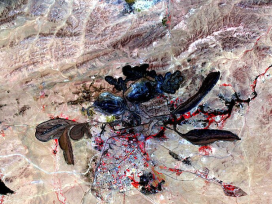

Excitement over ‘rare’ elements

Julie Klinger in conversation with Misha Glenny

The race for green transition supplies is on. But where’s the thrill in metals, discreet and hidden yet widespread? Mining, intensive due to low concentrations, throws up waste elements like arsenic. Space cowboys and deep-sea dredgers contest environmental stability more than China’s monopoly, based on 40-years of involved processing. Health and recycling regulations are a must.

Do the violence and oppression against Palestinians in Gaza and the discrimination and surveillance against migrants trying to cross European borders have more in common than meets the eye? A Belgian activist of the international Freedom Flotilla Coalition speaks out about the Israeli arms industry, institutionalized violence and human rights abuses.