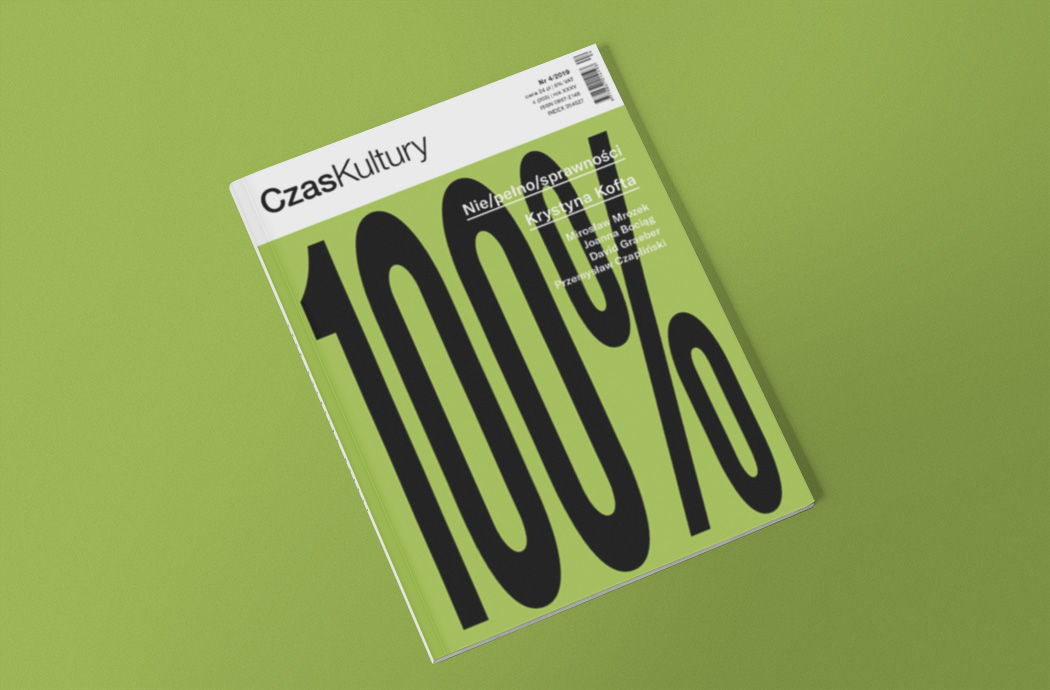

War veterans, discredited identities, pride and denial: Czas Kultury explores how the arts can help reframe the public perception of physical difference.

After World War Two, about ten million people returned to their homes in the Soviet Union with newly acquired disabilities. Of these, 90,000 had lost both arms and legs. Artist Gennady Dobrov’s haunting work ‘The Unknown Soldier’ – an image of an amputee with blazing eyes, wrapped in a sheet – appears in Czas Kultury, whose new issue explores how the arts can help reframe public perception of physical difference. Dobrov worked on his painting at a home for disabled war veterans on Valaam Island in Karelia, where – Piotr Krupiński writes – inmates were kept from the public eye in conditions comparable to those of the Gulag.

Identity

In English language discourse, feminism has helped activate disabled identity by drawing attention to the experience that shapes it, notes Monika Świerkosz. Just as, in Simone de Beauvoir’s words, ‘one is not born but rather becomes a woman’ so, for a disabled person, socialization implies growing consciousness of a ‘difference’ that must, where possible, be neutralized or corrected. The dominant social impulse is still to rescue people with disabilities from their ‘discredited identity’, the American disability studies scholar Rosemary Garland-Thomson has remarked.

In the Polish context, however, commentators have ignored the social pressures that shape disabled identity. People with direct knowledge of disability remain broadly silent and out of the public eye. Literature presents disabled protagonists mainly as symbols of innocence, suffering or exclusion. Little has been done in the Polish arts to creatively capture representations of self and body, or to question and invert them. It is a feature of laissez-faire capitalism in Poland, but more generally worldwide, that ‘denying disability, shaking it off and minimising it, is the most socially rewarded way of dealing with the disabled body.’

Difference

In an environment that ‘promotes and rewards self-help and selfhood’, a physically disabled male who has seemingly triumphed over his disability merges comfortably with heroic convention, Maciej Duda observes. ‘Growing into the community is associated with overcoming or denying one’s disabled condition, measuring up, and displaying characteristics that stereotypically awaken heterosexual admiration and desire … Marks of difference that have been overcome assume the significance of wounds or scars. They can be presented with pride – yet any sign of psychological difference, depression or failing mental health must be wholly erased.

Art

The late Rafał Urbacki’s dance show ‘Protected Species’ (Bytom, 2014) brought physically disabled performers to the Polish stage along with their personal stories of life in a society that delineates what is desirable, permissible or good. As Alicja Müller describes, the performers took control, introduced their own gaze, and unmasked ‘the discriminatory character of supposedly empathetic, ableist narratives’, exposing political correctness and normative thinking as ‘a coherent, closed and therefore non-negotiable, oppressive and exclusive vision of the world’.

More articles from Czas kultury in Eurozine; Czas kultury’s website

This article is part of the 2/2020 Eurozine review. Click here to subscribe to our reviews, and you also can subscribe to our newsletter and get the bi-weekly updates about the latest publications and news on partner journals.

Published 13 February 2020

Original in English

First published by Eurozine

© Eurozine

PDF/PRINTNewsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Related Articles

A leading Ukrainian-American writer on grace, justice, power and freedom.

'It’s important to be open'

A Knowledgeable Youth podcast

Remaining in a new country or returning home? The Knowledgeable Youth podcast delves into the complex decision-making refugees face when migrating, together with researcher Olena Yermakova.