Desertion is always an option

Clinging to his nukes, Putin will only lose power if his own turn on him. It’s hard to predict when, if ever, the leaders he has humiliated and threatened into submission will do the basic calculus and find that obeying the tyrant will inevitably cost way more than defiance.

Why should I be honourable? I’ll be laid out anyhow!

Why not then be honourable? I’ll be laid out anyhow.

Attila József, Two hexametres (1936)

The international community is now seeming to respond to public pressure following the invasion of Ukraine. The sudden display of willingness to provide active support in warfare – after an initial phase of tense waiting – is in sharp contrast to Russia’s annexation of Crimea and intervention in the Donbas and Luhansk.

On the frontlines and across the globe, people try to do their bit to defend Europe’s biggest post-Soviet democracy, which celebrated it’s 30th anniversary a few months ago. But how many individual decisions will it take to end a pointless war, the brainchild of one deranged autocrat?

This war has been ongoing for eight years, as many of our recurring authors have reminded, including Ukrainian public broadcaster Suspilne’s head of newsroom Angelina Kariakina and conflict reporter Nataliya Gumenyuk.

Yet, at the first signs of conventional warfare spreading beyond the Donbas and Luhansk, a suffocating feeling of powerlessness appeared in many concerned throats. Although the US had heavily publicized intelligence about the planned attacks, many doubted the possibility. Then, as the news came pouring in about Russian troops advancing toward Kharkiv and Kyiv, we waited for governments and international bodies to react and offer meaningful support to Ukraine.

What a pair of hands can do

What weight does one individual have in a fight with a military behemoth such as the Russian army? Very little, of course. But is that an excuse to stand by and save the effort? How many must break ranks to slow down evil? And how many must stand their ground to resist it?

This question has been asked by many, from Hannah Arendt to school bullying consultants. The odds are not encouraging. And yet, moral choices are heavily limited.

Painting by Ukrainian artist Vakulenko Y. Balance. 2021 Image by Paintgol, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

As more and more Ukrainians decided to take up arms and defend their country by any means possible, the international public started to search for ways to help them (see here for a selection by New Eastern Europe). The Baltic countries have spearheaded the effort, offering aid even before the violence started, and showing the same compassion as they have for the Belarusian opposition since 2020.

Public pressure has started exhorting responses, even from unlikely places. Indian president Narendra Modi, a dedicated trading partner of the Russian regime and no fan of democratic leadership himself, took to the phone to tell Putin of his disapproval. Even the Erdoğan administration gave in and announced it would close the crossing between the Bosporus and the Mediterranean to Russian ships and subs.

But the most stunning volte face has come from the German government, which brought itself to take decisive action – after much hesitation, having feared a potential economic recession, along with the Italian and the Hungarian governments. Germany’s energy policy has long been tied to Russia, and the North Stream projects may have even opened a window of opportunity for the Kremlin’s aggression, argues Andreas Umland.

As more and more announcements and offers come out supporting Ukraine, it has become much harder to choose comfort over courage. After a week of open combat and a heroic display of resistance, EU leaders have given in and pledged extraordinary support, including an unprecedented contribution of military-grade weapons. But one EU leader is still volunteering to throw a spanner in the works – the self-appointed champion of illiberalism, Viktor Orbán.

Forced to cut ties

In our latest conversation on the Gagarin podcast, Anton Shekhovtsov explains Putin’s big lie about the need for Ukraine’s de-Nazification. While Crimea has traditionally been part of Russian imperial mythology, the Donbas never has. To legitimize the incursions and eventual invasion, a tale has been fabricated about the oppression faced by Russian speakers in Ukraine, going as far as to falsely cry genocide.

Although the wider region has historically seen limitations on ethnic minorities’ use of their mother tongues, for Russian speakers in Ukraine it has never been the case, Shekhovtsov confirms. Indeed, as Timothy Snyder’ says: ‘“Russian speakers” in Ukraine are far more free … than in Russia. In Russia, there is no democracy for anyone.’

Shekhovtsov also points out that the war has rapidly forced most of Europe’s far right leaders to end their relationships with the Russian regime and take a stance against Putin’s aggression, regardless of how keen they had previously been to accept funding from them. It is also true that these friendships have not paid off politically for most of them.

One step forward, two steps back

There are a few notable exceptions though, the most prominent being Viktor Orbán. The Hungarian PM has allied so closely with the Russian autocracy that he now has a difficult time loosening those ties, above all in the energy sector. A replacement reactor for the Hungarian nuclear power plant in Paks has been contracted for with Rosatom under controversial conditions. Orbán is facing an election in a few weeks and his best card is the artificially low utility prices sustained by discounted Russian imports.

Orbán even visited Putin in February to appeal for an extra billion cubic metres in gas, the most important asset for the professed ‘fight against the utilities’. Characteristically for Fidesz, this social programme disproportionately benefits high volume consumers, but nevertheless throws a bone to a key issue of the Hungarian electorate: consumer volatility. In a captured state and under extreme media repression, what truly threatens the loyalty of isolated voters is a sudden drop in quality of life. Yet, with the Hungarian forint’s historical plummet in the past few days, no favour from Russia could hold the floodgates of wild inflation.

Orbán called his February visit a ‘peace mission’ and recommended the rest of the West employ the ‘Hungarian model’ to approach Russia – this he claims is a politics of mutual respect, even though Putin has made it clear he doesn’t think much of the illiberal PM.

Orbán has been trying his worst to hold back united efforts to support Ukraine ever since. Even his strongest ally in the EU, the Polish PIS government, is bewildered by this behaviour. PiS has at least remained consistent in their anti-Soviet stance, a position Orbán has long abandoned both domestically and internationally.

Bafflingly for a NATO member state and an EU leader, Orbán first tried to position Hungary as neutral in the conflict that has engulfed his biggest neighbouring nation. When forced to side with his official allies, he tried to avoid participating in performing the help expected – for instance, in refusing to let EU military aid cross the country on the shortest route to the border crossing of Záhony-Chop. Government apologist pundits are still propelling unfiltered Kremlin propaganda on TV; Ukraine-related Russian disinformation is rampant among Hungarian users on Facebook.

https://twitter.com/panyiszabolcs/status/1498978167478005761?s=20&t=PIBfs2_vZes1Yt1sWwDVLQ

While the government has exempted Ukrainians from its infamous ban on seeking asylum, it avoids admitting that refugees are entitled to help by shifting the focus to ‘our Hungarian brethren from Transcarpathia’ – that is, the sizeable Hungarian minority of Ukraine, many of whom have long acquired dual citizenship.

Love thy neighbour

In the meantime, civil society has risen to the occasion and rapidly started organizing direct aid to those seeking refuge in the country or travelling through. Drawing on the previous experience of the 2016 refugee crisis, NGOs, municipalities, huge numbers of volunteers and even the local joke party are building infrastructure to collect and allocate aid, and to provide lodging and services to those in need. The state railways have offered free travel for Ukrainain citizens; and people are offering to host refugees in their own homes.

This display of civil society strength and solidarity goes way beyond nationalist sentiment and recalls the humanity of those who rushed to help Syrians and others earlier. The main difference this time is that the organizers know how to go about it. Although the efforts are decentralized, there is a greater awareness of each other’s work, a readiness to cooperate, and skilled logistics to make the use of their full capacity. This is a token of the humanity that remains in Hungary and is a powerful force – even if it hasn’t overcome the threshold of an unfair election system in a captured state.

Truth be told, the Hungarian efforts are not extraordinary. Civilians all across the region and up to the Baltics are doing much the same. The main difference is that, in cases like Latvia or the Czech Republic, who have even allowed their citizens to go and fight alongside the Ukrainians, benevolence doesn’t have to swim against the stream. This allows them to realize their full humanitarian potential and provide more to Ukrainians who need it.

And importantly, lionizing the help of ordinary people implies that these efforts are beyond the spectator’s capacity. Donors, hosts and volunteers are doing something genuinely generous and altruistic, but hardly superhuman. Help is normal; kindness and compassion are part of everyday life. The only extraordinary thing is how a hostile political discourse has excluded vast groups of humanity from this normality.

What Russians can do

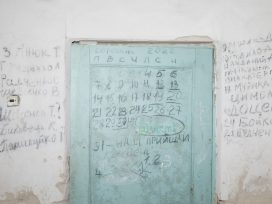

One hundred and five years ago, the unprecedented scale of desertion among Russian soldiers fed up with the pointless bloodshed, lead to the October Revolution and the eventual collapse of the Romanov empire. It wasn’t collective action though, but gradual demise, small groups of people deciding to take their fate into their own hands.

Volodymyr Zelensky is encouraging invading soldiers to do the same now: ‘Why do you need all this? … Leave your weaponry and leave. Don’t trust your commanders, don’t trust your propaganda. Just save your lives and leave.’

“Don’t trust your commanders, don’t trust your propaganda, just save your lives. Leave.”

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky calls on Russian soldiers to lay down their weapons and leave the country. pic.twitter.com/adN3G1Vmxl

— Channel 4 News (@Channel4News) February 28, 2022

Defence minister Oleksii Reznikov even offered a 5 million rouble reward and amnesty to Russian conscripts who capitulate. But while reports showing disoriented and undersupplied Russians, or wounded invaders apologizing may persuade those who are already predisposed to reject this aggression, Reznikov’s appeal will not win Ukraine this war.

Still, it makes a fair point: desertion is always an option.

The individual always retains at least a fraction of their freedom – even if it doesn’t save their lives, it could save them the humiliation of dying for something pointless and abhorrent.

It seems that Putin, more isolated than ever, has forgotten to motivate his own people. Evidenced by his discussions with high-ranking officials and advisors, he hasn’t sought anybody’s advice – or allegiance, for that matter. Least of all that of the Russian populus. For a long time, Putin’s policy has been all stick and no carrot; this invasion doesn’t hold a positive promise for Russians. As Igor Torbakov writes:

Driven by his imperial fantasies, historical nostalgia and resentment towards the West, Putin has decided to act without delay. Having cast his (and his minions’) interests as the national interests of Russia, he has plunged both Ukraine and his own country into the nightmare of fratricidal war.

Unlike Russians, Ukrainians know very well why they are in this war. Their pride is not enough to trump a military ten times their size, but it does win the hearts and support of many who have previously made a political career on refusing to help.

Clinging to his nukes, Putin will only lose power if his own turn on him. It’s hard to predict when, if ever, the leaders he has humiliated and threatened into submission will do the basic calculus and find that obeying the tyrant will inevitably cost way more than defiance.

Attila József, in his Two hexametres written in 1936, sums up the problem.

This editorial is part of our 4/2022 newsletter. Subscribe to get the weekly updates about our latest publications and reviews of our partner journals.

Published 2 March 2022

Original in English

First published by Eurozine

© Eurozine

PDF/PRINTIn collaboration with

In focal points

Newsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Related Articles

Despite the uncertainty of recovery from ongoing war, Ukrainians are confronting Russian destruction and de-construction with daily acts of reconstruction. Marginalized landscapes, histories and stories are being rediscovered through a grassroots resistance founded on loss, where language and naming reclaim cultural foundations.

The sharp drop in support for Ukraine in Italy has less to do with the traditionally Russia-friendly economic policy of the Italian right, and more with the anti-Americanism rooted in the political culture of the Italian left, which now articulates itself as pacifism.