Demodernization by missiles

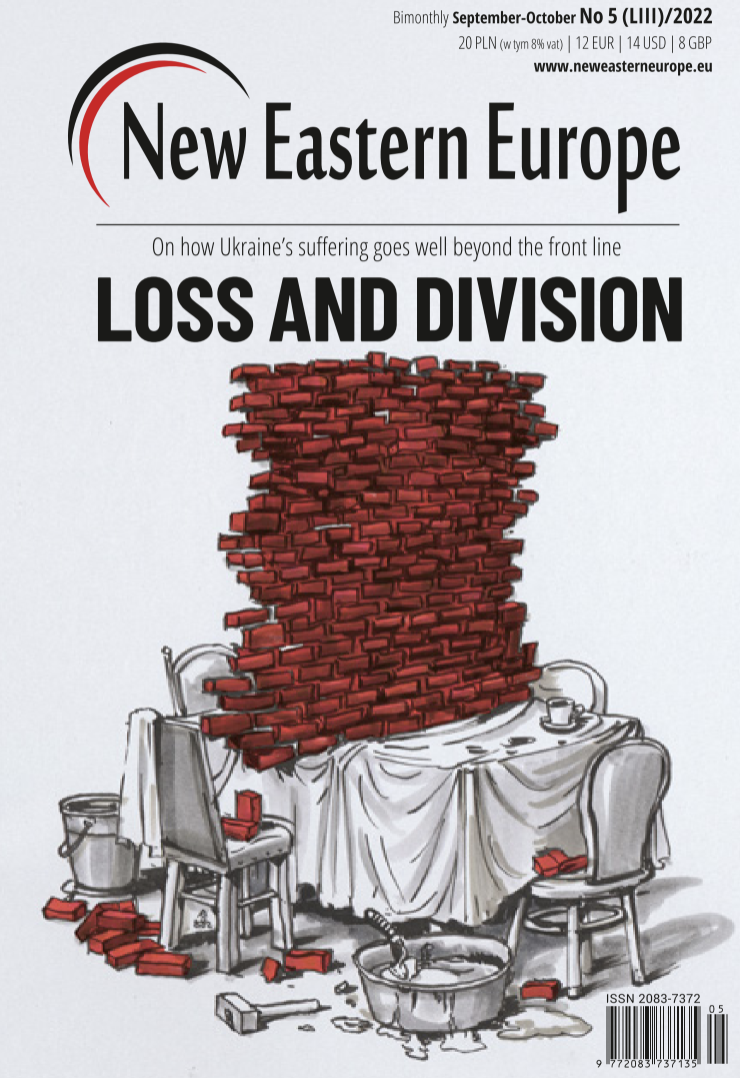

Infrastructure in eastern Ukraine has been decimated; business and manufacturing displaced; cultural artifacts destroyed; communities disrupted and families bereaved. In light of all this, the discussion about what Ukraine stands to gain from the war borders on cynicism.

Footprints, Ukraine. Image by Ilya via Flickr

More than 2,000 Ukrainian orphans from the occupied territories have been kidnapped and taken to Russia. There, they are to be ‘adopted’ by Russian families or brought up in military orphanages (‘cadet schools’). According to Ukrainian sources, 5,700 Ukrainian children in total have been deported to the Russian Federation. At the same time, Russia claims there are 450,000 displaced or deported children on its territory. It is hard to estimate the scale of the ‘re-traumatization’ caused by Russia’s policies of forceful deportations. They bring back not only painful collective memories of Stalin’s deportations to gulags but also thoughts of premodern slavery and human trafficking in the frontier territories.

Demographic spiral

This re-traumatization cannot be of little consequence to the social norms of bringing up children and the respective infrastructure. Ukraine was a post-genocidal nation before 2022 and it will be a ‘post-post-genocidal’ nation after the war. Jokes about overprotective Jewish moms may be funny, but those are ultimately the result of the traumas of the Holocaust and innumerable pogroms. Ukrainian moms may soon give a name to their helicopter parenting in their frontier country.

Similar to other Central European states, Ukraine was in the midst of a demographic crisis before Russia’s invasion. In fact, the Ukrainian population has been shrinking since 1990 – a year considered as ‘the maximum’ (when the population was more than 51 million). But that is not fully correct. If it was not for the cumulative effect of the series of genocides in the twentieth century (including the artificial famine of 1932-33 which claimed at least four million lives), the Ukrainian population could have potentially been at least 80 million in 1990, not 51.

Since 1990 the country has lost at least 20% of its population. Back in 2020 the birth rate in Ukraine was at 1.2% and the population was ageing. The current war has sped up this downward spiral. The current debate now focuses on how many Ukrainian refugees, mostly women with children, will come back home from Europe. It is obvious that at least some will stay, especially in the countries facing the same demographic challenges. In many places Ukrainians have started working and adapted to the new environment. At least some countries will encourage them to stay.

For Ukraine the demographic crisis is a menace and a long-term setback to economic development. The country is the biggest in Europe and so is its infrastructure. This means that in the future less people will be able to support the country’s transportation routes, electricity and water supply, heating, health care and education.

In economic terms a market of a small country, say 15 million people, is unable to provide a business the same opportunities to grow its output as a market of 40 million (many Ukrainian businesses do accomplish technological advancements that may surprise their European colleagues). Hence, the openness of other markets, first and foremost in the European Union, will be a matter of survival for Ukraine. And here is the big test both for the EU and Ukraine’s authorities and business communities. Will European countries use EU legislation mechanisms to favour and protect old members facing new competitors from the East, who are skilled and hungry? Will the Ukrainian authorities stick to their declaration of taking the European path? Will the Ukrainian business community be persistent enough to ensure the politicians keep their pro-European promises?

De-modernization of the East

No one currently knows how the general landscape of the country will change after the war (and who can even define ‘after’?) Even the most optimistic scenario – the fall of the authoritarian regime in Moscow – presumes that Russia will still be a cause of instability in the region for generations to come. This means that life on the frontier will constitute a risk. Ukraine will subsequently need a sort of military zone along its border. At the same time, some eastern Ukrainian cities are almost totally destroyed. In Rubizhne in the Luhansk region, for example, 90% of its pre-war infrastructure no longer exists.

Rubizhne as a town grew out of a settlement for those who built a railway station in the late nineteenth century. Later, it was a city for the workers of an established local factory. The name of the town itself can be translated as ‘frontier’. Before the railway, in the early modern history of Ukraine, Rubizhne was a paramilitary settlement of Ukrainian Cossacks. It was literally the frontier between Slobidska Ukraine and the Wild Fields – the steppes of modern-day Ukraine’s eastern and southern territories alongside southern Russia. But now, after so much has been destroyed, it may return to its previous status as a wild frontier. One could wonder if there is any sense in rebuilding this town, if there are no jobs, infrastructure or prospects for the people.

The ruined industrial east of the country is a palpable example of de-modernization. In this case, it is a de-modernization by missiles. Hence, it is very likely that the region may once again become what it was during the seventeenth century: a military belt and a frontier between European civilization and a menacing, backward despotism.

As Ukraine keeps losing infrastructure in the big eastern cities – one of the biggest and most important is Kharkiv, under regular attacks – some parts of them are now hardly liveable. In the case of Kharkiv, the border with Russia is just 50 kilometres away. Chernihiv is not as big but also badly damaged. Back in May the mayor said 70% of the city’s infrastructure was destroyed (other sources confirmed the damages of at least 20% of the residential buildings). Chernihiv is now rebuilding its local power plant. The city will hopefully have heating this winter. But will it have investments?

As of mid-July, more than 600 production facilities had already relocated to western Ukraine. Almost 500 others were looking for a place to relocate. These are the official statistics regarding businesses that applied for assistance to move operations. But not all businesses applied for aid. Many IT specialists essentially have their facilities in a backpack. As for these relatively well paid, young, and adaptive people, up to 57,000 (mostly women) of a total 285,000 left for other countries. According to research by the Lviv IT Cluster, 27.8% of the IT community was living in eastern Ukraine in December 2021. Now, only 10% remain there. In May 2022 the IT community in the western region grew from 16.5 to 24%. According to the same research, 57% of IT specialists would prefer to stay in Ukraine.

Avenue in Rubizhne, Luhansk oblast, Ukraine. Image via Wikimedia Commons

The destruction of Ukraine’s industry also means massive ecological problems and many of them are still unknown. For example, the Chornobaivka poultry farm in the occupied Kherson region, one of the biggest in Europe, was totally cut off from electricity due to the blockade. More than four million chickens died and there were no means for proper disposal. The chemical traces of the shelling, fires, abandoned productions and the erosion of the soil are hard to estimate at this point as most of the affected territories are still occupied. How much of it will be inhabitable after liberation? No one knows. However, it is certain that what is happening in Ukraine is giving a new twenty-first century meaning to the expression ‘scorched-earth policy’.

Inherited trauma

Ukrainian historian Yaroslav Hrytsak noted in his latest book on the history of Ukraine Overcoming the Past: The Global History of Ukraine (published a couple of months before the invasion) that the country has faced numerous traumas related to war and revolutionary violence. One of these traumas is related to material loss. ‘By 1991, when Ukraine became independent, it was hard to find a Ukrainian family where a property would be inherited through three generations – from a grandfather and a grandmother to a father and a mother, and from a father and a mother to a son or daughter. Few belongings were left: an old, yellowed photo, an embroidered shirt from a box, a musical instrument. There are almost no precedents of inheritance for three generations of major family assets: homes, jewellery, shares or savings. Every generation had to start from scratch.’

I am writing this text while sitting in the modernist quarters of Lviv. The very nice and comfortable residential buildings were built here around 1935-39, just before the first Soviet occupation of the city (followed by the Nazi occupation before returning to Soviet rule). Their residents were either deported (if Polish or Ukrainian) or killed (if Jewish). The luckiest fled to Poland or further on to Great Britain, France or the US. They had just a few years in these then brand new, fancy apartments before all hell broke loose.

This is the same story now facing those residents of Irpin or Bucha. These two Kyiv suburbs are the most well-known, but there are a lot of small towns and villages in the regions of Chernihiv, Kharkiv and Kyiv where the atrocities committed by Russian troops were as horrible as those in Bucha. One of the possible reasons for the attention placed on Bucha is that these suburbs were the places where the growing Ukrainian middle class had recently moved. There, they found new, comfortable apartments with good infrastructure for families with kids. Many of the residents were the first generation in their families who had bought their own property. Many of them remembered the misery of everyday Soviet and early post-Soviet life, and had finally found some comfort. Starting from scratch, they had inherited only trauma from their grandparents. And now they have their own.

Oleksandr Mykhed and Olena Mason are some of those who lost their home in Hostomel. In a Facebook post on 6 March 2022, Olena published a list of their art collection they had lost there. Oleksandr is a literary critic, and he lost his library full of rare and precious books he had been collecting. This is also a part of the catastrophe that should be respected as much as the loss of necessities. It is easy to say that ‘it’s just stuff’. Those who inherited paintings, photos, furniture, books, through three or four generations, just cannot understand how it is not to have all these pillars of memory, how much self-confidence they provide and that this self-confidence is indeed capital. Museums, libraries and art collections barbarically destroyed by Russians in Ukraine should also be counted as capital, not just ‘stuff’. The loss of stuff makes people poorer for some time. The loss of culture, including personal and collective memories, makes a society poor in the long term.

Looking at the bright side

All the above does not necessarily mean that the country is doomed. In fact, it is the exact opposite. At some point there is more hope than there was before. However, it is not a question of what will change for the better, but how to talk about it. Most Ukrainians who lost housing in big cities were living in ugly and uncomfortable Soviet buildings. The Ukrainian government has already declared that it will pursue a policy to ‘rebuild better than before’. Yet, how can one speak openly that it is better for a city to have a nice new residential area instead of a depressing old one in front of the people who lived there? The issue concerns not only those who lost their homes, but also their beloved neighbourhood, no matter how unattractive it may have looked to an outsider.

Some say that having lived for some time in Europe, Ukrainian citizens will come back with new demands, that they will expect more rules at home. Some may also imply that they will have become better citizens. Overall, the presumption is that the war makes those of us who survive better. The discussion as to what we gain in war inhabits a space between common sense and cynicism.

Yet, even if we allow ourselves to entertain the thought that the war makes people change, and that these changes are for the good, how much can we expect? For instance, it might appear that having experienced the Russian occupation, shelling, or just living next to a genocide in your own country, that any pro-Russian sentiment would be reduced to zero. Yet, 11% of Ukrainians as of July 2022 thought that Ukraine and Russia should be independent states with open borders and that the two countries should live on friendly terms. The good news is that back in February 2022 this figure stood at 48%. The bad news is that there is still this 11%. Who are these people?

You would think that this 79% figure of Ukrainians who prefer visas for Russians and closed borders would be higher in the current circumstances. However, the number is good enough for the country’s respective policies. When we investigate the dynamics of the numbers, these policies appear not only doable but also sustainable. The number of those who support the country’s western choice has been growing. Conversely, the number of those who support closer links with Russia has been shrinking. The thing is that these changes were not fast enough to follow the path taken by other Central European countries back in the 1990s. But now the war has sped it up.

Professor Hrytsak, the Ukrainian historian mentioned above, wrote at the beginning of the invasion that any war is a time accelerator, and that it makes previously impossible things possible. If so, it is safe to expect that the changes that started before the invasion will accelerate. Ukraine has already received EU candidate status, progress that was unthinkable even last autumn. But this does not mean that good news just appeared in Ukraine, it means that the country’s efforts and hard work are keeping it on a path that is paying dividends.

One last, critical change needs to be considered and it affects more countries than just Ukraine. Namely, if Ukraine does not win this war, all our political presumptions are just talk. If it does not win this war, the world will lose much more than a free country. It will lose everything that was considered progress during the last century: faith in freedom, justice and human rights. This potential change shouldn’t be a surprise. After all, the corruption of the West through Russian and Chinese money and the helplessness and complacency of international organizations didn’t appear yesterday. The accelerator of change works in both directions.

Published 12 October 2022

Original in English

First published by New Eastern Europe 5/2022

Contributed by New Eastern Europe © Oksana Forostyna / New Eastern Europe / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTPublished in

In collaboration with

In focal points

Newsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Related Articles

House keys recur in the stories of Crimean Tatars and Palestinians displaced from their respective homelands in the 1940s, and Ukrainian citizens fleeing Russian invasion since 2014. Ethnographic research and discourses on art and justice show how objects emblematic of home salvage the history of exiled peoples from oblivion.

As capital consolidates, culture recedes, funding vanishes, access narrows. The question persists: why fund culture at all? Cultural managers from Austria, Hungary and Serbia discuss.