In New Humanist, Isabella Kaminski explores the ‘burgeoning field of climate litigation’: activists across the globe are dragging countries and governments to court over their lack of meaningful action on environmental issues. Their demands rest on internationally recognized principles of intergenerational equity.

‘But while the young are increasingly advocating for themselves in our legal system, there is more work to be done to change attitudes in society.’ The self-interested homo oeconomicus treats the future as ‘a distant colonial outpost where we can freely dump ecological degradation and technological risks as if nobody was there,’ philosopher Roman Krznaric tells Kaminski. ‘When we see ourselves as more cooperative creatures we start designing institutions that way.’

In some countries, ‘long-term thinking is starting to be built into legislation’. Wales has a future generations commissioner, the Finnish Parliament a Committee for the Future. ‘But determining the needs of the unborn isn’t always easy,’ writes Kaminski.

What we need, then, is a shift of mindset. For Krznaric, being a good ancestor means ‘caring about the universal strangers of the future’.

Copernican trauma

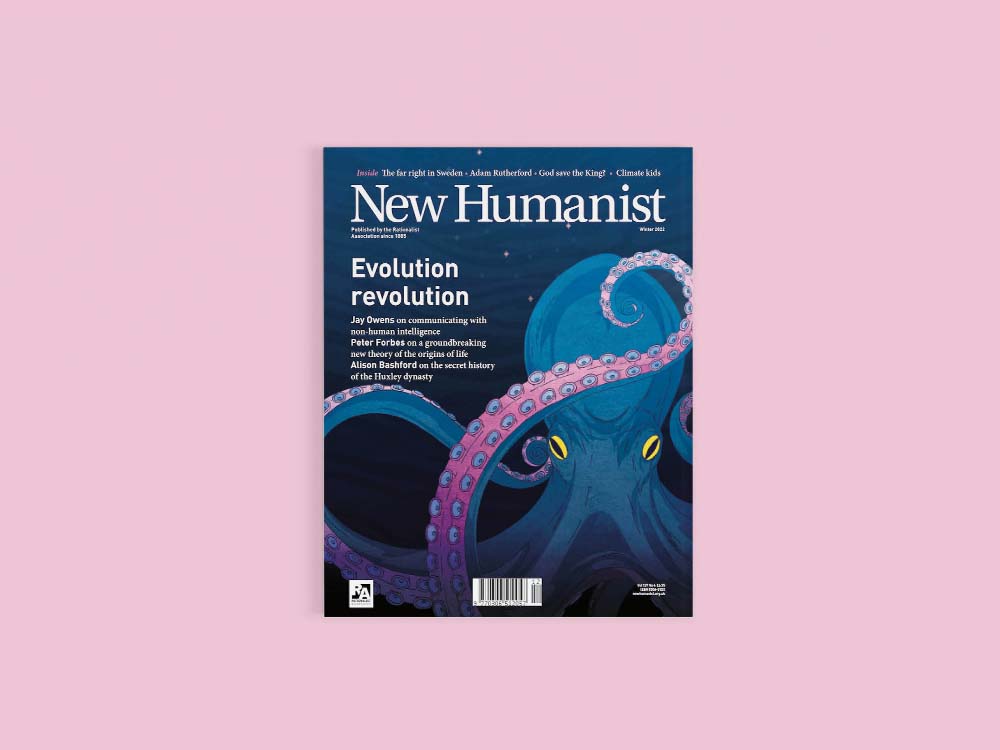

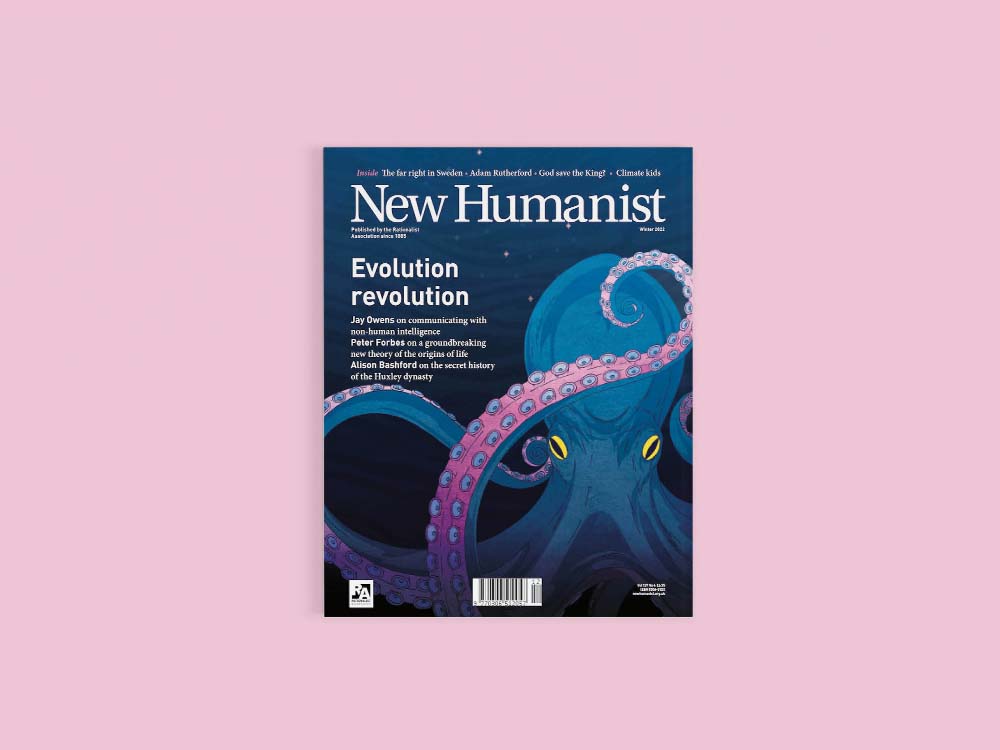

A more sustainable relationship with the planet may follow from an expanded definition of intelligence – be it human, vegetable or machine.

Jay Owens draws on two recently published books – Ways Of Being by James Bridle and The Mountain in the Sea by Ray Nayler – to explore the traits of more-than-human thinking: it isn’t ‘just about recognising the near-to-human cleverness of certain animals, but recognising agency and interdependent relations across every kingdom of life, from the single-celled extremophiles known as archaeans, to fungi, animals and plants.’

Artificial intelligence, too, is a crucial element of this new ‘technological ecology’. ‘Our recent creations might not distance us from nature, but instead help us better understand the collaboration and teeming complexity of the natural world.’

It is a new cosmology that once again removes man from the centre of the universe. Traumatic? Maybe. Yet ‘the ultimate gift of this more-than-human thinking might be to make us more humane’, Owens comments.

Read Jay Owens’s article in Eurozine.

Meet the Huxleys

Alison Bashford sketches an intellectual history of the Huxley family, from ‘Darwin’s bulldog’ Thomas Henry Huxley to his grandsons Julian, the biologist, and Aldous, novelist and philosopher.

‘Over the 19th and 20th centuries, this dynasty of philosophers and scientists profoundly shaped how we see ourselves: all humans are part of, not separate from, nature. Humans, like everything else living, are necessarily part of evolution by natural selection. Yet the Huxleys searched also for meaning and transcendental experience’.

Thomas Henry Huxley coined the term ‘agnostic’, but always intended it as a statement on epistemology rather than the divine. ‘For this particular agnostic, theologies and cosmologies were almost as fascinating as primate skulls and the cells of jellyfish.’

Julian Huxley was ‘as card-carrying a humanist as it was possible to be’. Yet the evolutionary humanism he embraced became ‘glossed by a neo-Romantic vision’. For both Julian and his brother Aldous, the author of Brave New World, Romantic nature and ‘her trustees’, the poets, represented a powerful pole of attraction.

Aldous sought ways to experience transcendence ‘through words, through meditation, and finally through his death-bed injection of mescaline, which his wife called “a sacrament”.’

Review by Alessio Giussani