It was about 20 minutes past midnight in the early hours of 25 April 1974, when ‘Grândola, Vila Morena’, the song that would become the anthem of Portugal’s Carnation Revolution, was broadcast by Rádio Renascença on its Limite programme, heard in every barracks across the country. It was the second signal (after Portugal’s 1974 Eurovision entry, ‘E Depois do Adeus’ by Paulo de Carvalho) issued to let the troops know that the coup that would topple the country’s authoritarian regime was really going ahead. The revolution was underway.

Initially, the radio station was unsure whether to ignore the event entirely or follow the coup closely and report on it in its news coverage. Station management ended up opting for the latter, and the revolution was reported step-by-step throughout the day on the Catholic radio station. This is described in the article ‘Radio Renascença during the transition: from 25 April to 25 November’ by Nelson Costa, published by the Centre for the Study of Religious History, part of the Universidade Católica Portuguesa, in 2000. ‘Reporters followed events that day, notably in Largo do Carmo and at the PIDE-DGS headquarters’, it reads, referring to the square in Lisbon where people began gathering in April to demand the resignation of Marcelo Caetano, who had led the regime since succeeding António de Oliveira Salazar in 1968.

Despite the undeniable historical importance of these recordings, they have largely been lost. Even the beacon signal of ‘Grândola’ itself and the programme that played it were not fully archived by Rádio Renascença (RR). In the station’s archives, there is a digital track which plays the presenter’s introduction and the beginning of Zeca Afonso’s song. According to Ana Isabel Almeida, coordinator of the Renascença Multimedia Group’s archive, which owns the RR, RFM and Mega Hits radio stations, there are also recordings of some reports of subsequent events in Largo do Carmo, but there are no organized archives that have preserved that day’s radio broadcast.

It is not currently possible to ascertain whether there were any efforts made to preserve the recordings collected that day for future generations. In the post-revolutionary period, RR, like many other Portuguese media organizations, experienced a great deal of upheaval and was subject to shutdowns, restructuring and occupations by striking workers and radical left-wing groups. A lot was destroyed. ‘The company underwent a lot of difficulties’, explains Almeida, who blames this for the loss of a lot of historically relevant material.

What’s more, many of the programmes were the responsibility of external producers and ‘Renascença didn’t keep anything’. ‘I assume they just didn’t think that it was necessary to keep it’, she says. In addition, analogue recording materials were expensive and were therefore taped over several times after each broadcast, a common practice at the time. The loss of these unique historical records can therefore be attributed to a number of factors.

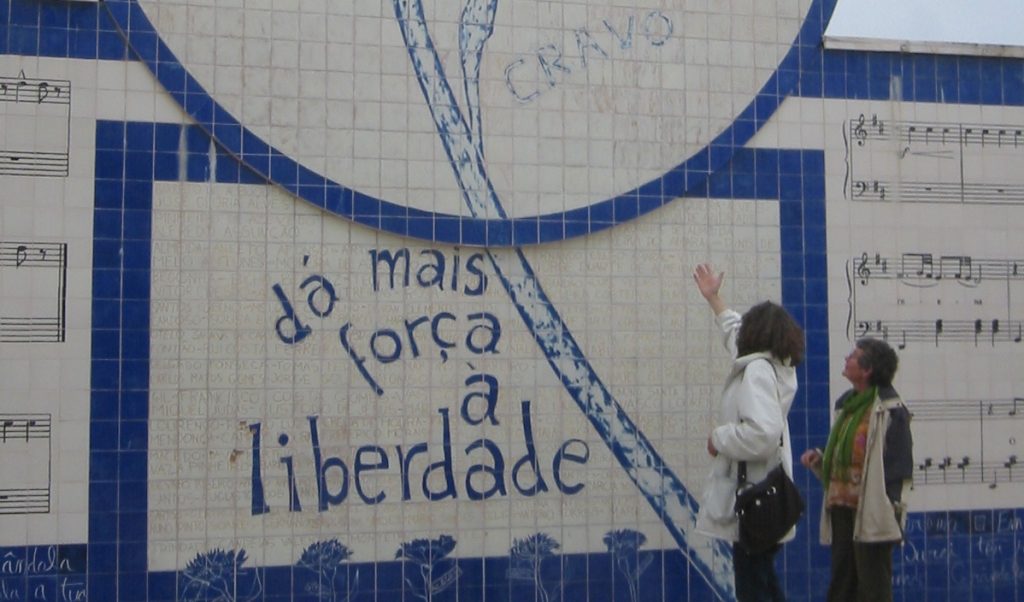

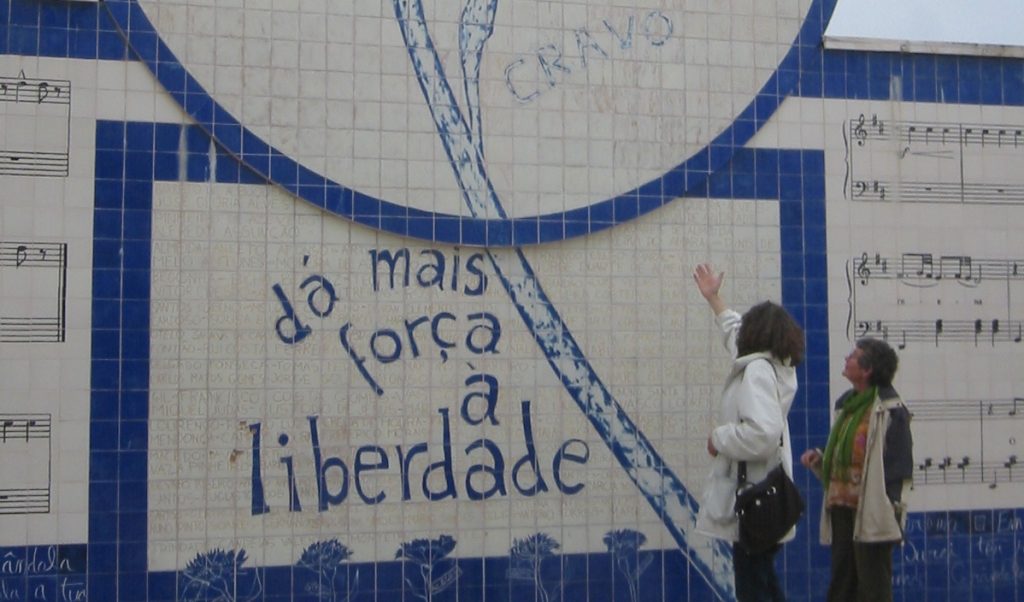

Monument to Portugal’s Carnation Revolution, Grandola, made by Bartolomeu dos Santos, Zeca Alfoso, 24 April 1974. Image by Claus Bunks via Wikimedia Commons

The case of RR is just one example of the historical lack of standardized practices in the Portuguese media archives. This is not a new phenomenon and there are various reasons for it: a lack of resources for maintenance and preservation, the cost of the analogue instruments that were used, the political instability in Portugal after the revolution – which led to the nationalization and temporary occupation of a number of media organizations, the priority given to delivering daily news, or even a simple decline in interest in record-keeping. This was particularly significant in radio, where there was a lack of legislation requiring archiving.

Cláudia Henriques is a researcher at the Centre for Communication and Societal Studies at the University of Minho, whose research focuses on radio journalism. Her doctoral thesis centred on radio archives in the Iberian Peninsula, and her discovery that there was a dearth of archived material ended up damaging her research. ‘I wasn’t able to write the dissertation I wanted, but rather the dissertation that was possible’, she says.

The lack of archives, she explains, ‘hinders our ability to understand the past and historical reality’, and this not just a problem of the past. The archiving of radio news content ‘is very haphazard, it’s very much at the whim of the client, and it’s very much up to those running institutions as to whether to safeguard the material’, says Henriques, who worked as a trainee at RR.

One of the problems is a lack of legislation guaranteeing the archival of radio content archives, with the result that material continues to be lost to posterity.

‘There is a legal vacuum. There is no national law around archiving in Portugal, which is a necessity and has been in demand for a while, but has not yet been forthcoming’, says Paula Meireles, archivist and vice-president of the Portuguese Association of Librarians, Archivists and Information and Documentation Workers, who believes that the existence of a wider law would also benefit media archives.

An analogue law in a digital world

Legal deposit, which ensures the archiving of all printed publications – both periodicals and monographs – via mandatory submission to the National Library, has no equivalent in radio or other media. There is no express obligation to archive radio, digital or multimedia news content. The law, last amended in 1982, only considers paper copies relevant in preserving collective memory, as far as journalism is concerned. Although the law governing legal deposit mentions ‘works printed or published anywhere in the country, whatever their nature or reproduction system’, the truth is that this rule is not applied.

Newspapers and magazines are therefore subject to legal deposit, but so are supermarket brochures, special interest or astrology magazines, atlases, teaching materials, statistical graphs, geographical or building plans, printed musical works, theatre and other cultural programmes, exhibition catalogues, illustrated postcards, stamps, prints, posters and engravings. Audio and video recordings, cinematographic works, microforms and other photographic reproductions are also covered by the law, but these are not collected by the National Library. ‘Given the specific nature of this library – essentially only printed works – legal deposit has never been implemented for non-print works’, says Miguel Mimoso Correia, director of general library services at the National Library.

In the case of film, the Cinemateca Portuguesa (Portuguese Film Institute) is responsible for its preservation and dissemination. As far as audio recordings are concerned, the proposed National Sound Archive, only now being set up, could fulfil this role.

Legal deposit was first regulated by Law 19/952 of 27 June 1931. The law was updated in 1982 to keep up with ‘the evolution of media reproduction’ and ‘social, political and economic changes in the country’, as well to make the process ‘more efficient and less cumbersome’. It was amended again in 2006 and 2013 to include postgraduate and doctoral theses. No changes were made to this law to include other news media, with the exception of PDF files, which usually feature paper editions of the same newspapers.

The Portuguese cultural journal Gerador has tried several times to contact the Ministry of Culture to clarify this and other issues but has received no reply: requests for information are merely referred to the relevant authority, the Directorate General for Books, Archives and Libraries.

According to Silvestre Lacerda , who was the head of this organization at the time of writing, responsibility for legal deposit belongs solely to the National Library, an autonomous body that complies with a law that can only be changed by Portugal’s Parliament, the Assembly of the Republic. Despite this, he agrees that there is a need to rethink existing legislation. ‘I think it’s worth a closer look’, he told Gerador, giving websites and their volatility as an example.

Silvestre Lacerda points out that digital and audiovisual content cannot be collected by the National Library in the same way as printed materials, as it is simply not feasible to collect all photographs taken in the present day. ‘We’ll have to find ways of evaluating and selecting documents that may be important to our national heritage in some way’, he says.

The National Library currently receives between ‘15,000 and 18,000 entries per month, via legal deposit’, figures that include both monographs and periodicals, according to Miguel Mimoso Correia.

Entering the library through its delivery doors gives you an idea of the logistical complexity involved in collecting this work. Piled-up boxes reveal the lack of resources needed to speed up the whole process, which involves individually checking the number of copies of each issue and notifying senders when something goes wrong.

In addition to the Portuguese National Library, there are 11 other legal deposit libraries located in Portugal (nine on the mainland, one in Madeira and one in the Azores), as well as two others in former Portuguese colonies that continue to function by special agreement: one in Macau and one in Brazil (the Real Gabinete de Leitura Portuguesa in Rio de Janeiro). The first delivery is made to the Portuguese National Library, which is then responsible for sending items or notifying the other recipients to come and collect them. ‘It means that the publishers always send us everything that is published, which is a big challenge, because then we have to keep checking to see if what has been published has been received or not, so we have to check the guides all the time’, he explains.

‘Then we have a lot to do and a lot of paperwork to deal with, then comes the document processing and then there are the library’s processing systems, which allow the reader to go to the catalogue and search for what they’re looking for’, says Correia. He adds that this leaves a gap between receiving the publications and making them available to all citizens over the age of 18.

‘In terms of legal deposit, the library is successful in achieving that’, he explains. ‘We are preserving information and enabling access to it for the general public. To that extent, it’s a model that works’. Despite this, Correia admits that, because the legal deposit law dates back to the previous century, there may be ‘a mismatch’, not least because it does not account for digital materials. However, he says that the National Library would not have the means to archive other formats, not least because that is not its purpose, since the organization’s focus leans more towards ‘dissemination and access’ rather than preservation (though it does end up doing this as well).

Correia explains that centralizing an archive containing newspapers, printed works and the output of every single media outlet would involve huge additional effort and would essentially change the purpose of the existing organization, from a library to an archive. ‘It would be logistically difficult, requiring space and resources. Centralizing isn’t necessarily a silver bullet. It has to account for human resources, a huge and diverse number of past historical events, and the unique nature of different institutions; I just don’t think it’s feasible to have a single institution do all that’, he says.

Gerador contacted all parties with parliamentary representation – Partido Socialista, Partido Social Democrata, Pessoas-Animais-Natureza, Chega, LIVRE, Iniciativa Liberal, Bloco Esquerda and Partido Comunista Português – to find out whether any of them had explored new policy concerning media archives and legal deposit, but almost all were either unavailable or unresponsive. Only LIVRE MP Rui Tavares provided a response, saying the following by email: ‘It’s an issue that concerns us and, in the future, we would like to bring forward proposals on this issue’.

Gerador also contacted the Portuguese Committee on Culture, Communication, Youth and Sport. A committee clerk replied that ‘I wish I could help you, but the truth is that there is not – and has never been – any movement on this matter’.

A lack of objective criteria

Returning to Rádio Renascença, the station is only mandated to keep recordings for 30 days, given that the law on legal deposit does not apply to digital audio. This is mostly in case the material is needed for right of reply or legal evidence, if applicable, and this timeframe can be extended by court order. The same law that mandates this, published in 2010, mentions an obligation to ‘maintain and update sound archives’, but does not lay out how this is supposed to be done.

‘I think it would be game-changing to have legal deposit [for radio], not least because the French experience shows that it works,’ says researcher Cláudia Henriques, referring to a law that, unlike the Portuguese one, considers legal deposit by content and not by medium.

Although the station was founded in 1937, systematic news reporting only began on Rádio Renascença in 1972. The department responsible for documentation only began in 1990, initially focused on researching daily briefings for journalists. It provided a summarization of the major issues of the day. ‘This department evolved and took on new media only when required,’ explains Ana Isabel Almeida, the co-ordinator of the company’s archives.

It wasn’t until four years later that in-house content began to be stored, and the current archiving policy is at the discretion of the person in charge, the department’s sole employee. There are no codified criteria for archiving, and sounds are stored on the basis of ‘relevance’.

The broadcaster’s historical collection is dominated by its discography, made up of 46,000 works that are ‘now catalogued’. Almeida estimates that there are around 50,000 vinyl discs in total.

In its sound archive, there are ‘61,000 sounds’ in digital format relating to past programmes, along with 500 cassettes and around 200 reel-to-reel audio tapes. A large part of this collection of news content is not catalogued.

Today, Almeida ‘rescues’ interviews and content that may be relevant in the future. Interview programmes are usually saved in their entirety, as they can be used in reports in the future. Yet the day-to-day running of the station also takes priority. ‘If I can find the time, I will archive as much as I can,’ she says.

The translation of this article, first published by Gerador, was commissioned as part of Come Together, a project leveraging existing wisdom from community media organization in six different countries to foster innovative approaches.