An event, a date. A brief moment of violence and deliverance: the world stumbles, loses its balance and recovers. Political conversations converge on that extraordinary moment. Soon enough, the particular event becomes infiltrated by new interpretations, expectations and disappointments. Inflated, it detaches from time and place like a balloon and, depending on conditions, changes course.

Upheavals like the one seen in 1989 are not new in European history; shattering departures from the past, with lasting aftershocks that disrupt the future. A missed heartbeat; sudden euphoria triggered by promises of rapid, fundamental change, which eventually turns to weariness. What do we want with our revolutions? Seen from just a short distance, they look different, both treacherous and betrayed. And the further we look into the past, the more thoroughly each generation seems to have set about dismantling its heritage.

The Russian revolution had been going on for seventy-three days, one day longer than the Paris Commune, when Lenin danced in celebration in front of the Winter Palace. Had the Commune not already been designated a failed revolution, then it would have been at that moment.

And yet, the Commune was neither ‘a revolution’ nor, despite its bloody suppression, ‘a failure’. Those who fought for or supported it often spent more seeking work than working. Many were artisans who took pride in their skills: they were bronze smiths, engravers, lace makers, woodcarvers. Opportunities for practising their trade were becoming scarcer as industrialisation took hold.

The struggle for the Paris Commune and the ideas that sustained it focused to a great extent on the right to own the fruits of one’s labour. The Commune was a mirror for the Russian revolutionaries. Much that had been desired back then coincided with the goals of the Russians; dancing must have been irresistible when the Bolsheviks saw how much more successful they had been.

At times of dramatic change, history provides important insights. However, the historical narrative must first be elaborated, sifted through and reshaped. Only then can insights raise awareness, encourage activists and onlookers, and offer hope for the future. Can we really have forgotten that a war came to an end in 1989? True, it was a Cold War – at least in Europe. It was the desire for peace that led to the fall of the Berlin Wall. But has deliverance and hope of reconciliation had the consequence of cooling down the memory of communism? Was there a reason why the memory needed to be hurriedly frozen and its intensity eliminated? Memory was an obstacle, not only to reunification, but also to the East’s aspiration to demonstrate how much more it had to offer than its immediate past. And it also enabled the West, guiltless and curious, to approach and invest its resources in the East.

*Our notions about the future depend entirely on our experience. Those who lived in the East were exposed to experiences that had no relevance in post-1989 Europe. As they confronted parallel, irreconcilable layers of phenomena, it became impossible for them not to be at odds with the new. The Swedish journalist Richard Swartz said that he wrote his book

Room Service: Reports from Eastern Europe in order to rescue the memory of ‘what it was really like’ during the thirty years he had worked as a foreign correspondent in Poland, Czechoslovakia and some of the Baltic States. However, his Ranke-like goal was tempered by self-mocking uncertainty – we are all prone to mixing memories, blanks and distortions in about equal proportions. But it was always the same phantom that spooked every chapter, haunted the bodies and minds of half the population of Europe. We now run the risk of forgetting or distorting the cause of Europe’s pathology: Communism.

The other day, someone told me (I have forgotten who) that Prague is a pleasant and lively city, full of houses in happy pastels and American students sitting in the cafés, working on The Great American Novel. But that’s not true; everyone knows that Prague is a colourless city, full of dogs and construction sites where, if you go out at night, the only person you will encounter is some solitary, bewildered soul who has lost the key to his apartment building. If anybody in Prague is writing anything, it is political slogans like Eternal Friendship with the Soviet Union.

Room Service was one of the most important books I read in the mid-1990s. I was 26 and had recently moved to Berlin. I read it many times in Swedish; when the German translation was published, I read that too. So that no one could trick me later. Things really had been different in the East. Soon they would become even more different. This was clear even at an early stage.

Swartz’s writing was imbued with the legacy of long delayed Enlightenment, with the moodiness of the Czech masters, with the voices of Bohumil Hrabal and Václav Havel. Of course, truth exists. And, of course, ordinary people can generate enough force to drive change. Only, it is exceptionally rare for truth to be reached and for society to really change. Swartz already felt defeated: no one will remember, he thought. He understood that the recent past would fade from the collective field of vision. Four decades of totalitarianism with disastrous economic and ecological effects would be reduced to little more than a transparent screen behind which people in the West could discover the true Europe.

*Europe is still divided by people’s experience of Communism. Worlds divide those who were part of the eastern past and know about it in their bones, and those who only studied it and visited the places they had read about. Such a swift transformation is unprecedented in history: a region, or almost half a continent, suddenly became a pleasing antique and subject of guesswork.

Photo by Tamás Urbán on Fortepan. 1990. Germany, Berlin, Adalbertstrasse 32.

During the 1990s, the true Europe could indeed come across as enticing. The landscapes flourished and property owners invested in the community. The citizen was at the centre. It was where the best developments before the First World War had fused and created a world of intimate urban settings, of economic and artistic freedom, while including all the contemporary gifts of the post-1989 world: communication, openness and democracy.

Suddenly, the borders opened. The streams of people crossing them did not only move from East to West. Many, driven by heart-breaking longing for Europe, travelled from the West to the East. Look! we called out to each other as we started wandering around the cities. What we pulled down is still standing here. Here they still have on show all the old features we have covered up. This is the Europe we all wanted to keep. The cracked future that would never happen.

Anachronism was a wonderful religion and it was everywhere. It prompted pilgrimages. It offered opportunities and liberation. Imagine! we said to each other – citing both Margaret Thatcher and Francis Fukuyama – that an alternative was actually so close at hand! And unlike the future, it isn’t even insecure.

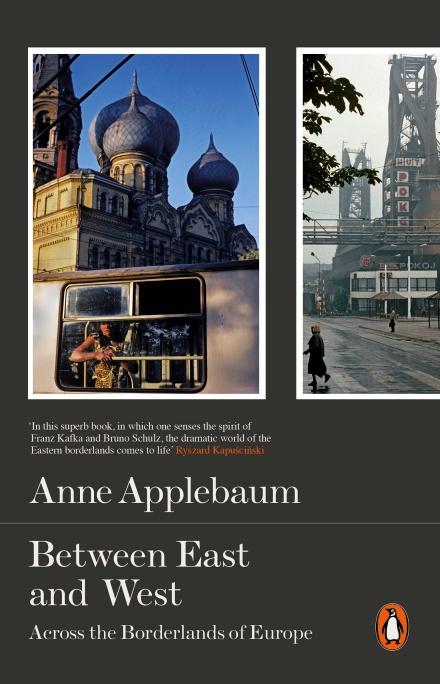

There were other books forming part of the heritage of 1989. When I pick them out from the bookshelves, the sight alone sends shivers down my spine. I ploughed through Between East and West by Anne Applebaum in one sitting. In it, she describes a journey that took her through border territories from Kaliningrad to Istanbul. Her travels mostly took place around 1990. Applebaum sometimes refers back to a period she spent as a researcher in the Soviet Union during the 1980s. She had become used to the checks on foreign students, including the required travel permits and predetermined routes. But, just once, the system of restraints broke down: the train from Leningrad had to make an unscheduled stop for repairs in L’viv, the formerly Polish city in western Ukraine. The passengers were allowed to leave their seats and look after themselves in the city for five hours. As she stepped off the train, Applebaum felt that she was doing something uncanny. She had entered into the borderland for the first time. ‘It was as if someone had told me that it was possible to walk into the picture frame.’

She wanders and finds herself in a cemetery. ‘All around me, laid haphazardly one beside the other, were a thousand monuments to L’viv’s confused history.’ She pulled away leaves and weeds from one tombstone and saw the inscription K & K, which stands for Kaiserlich und Königlich – ‘Imperial and Royal’ – the symbol of Austro-Hungary. There were Greek Catholic crosses, Orthodox crosses and more recent Soviet graves topped by red stars, as well as stones with text that the passage of time had made unreadable but with carved images of weeping poets in poses suggesting imminent death. All these dead have been stacked on top of each other in a place of burial that contained so much secret history but was concealed in ‘the dull Soviet landscape and behind boring regulations’.

This is one of the archetypal scenes in Europe after 1989. I have lost count of how many times I have done the same: wandered around Orthodox, Catholic and Lutheran cemeteries or Muslim and Jewish places of burial, experiencing the powerful subterranean force of diversity. To stand among the forgotten and the dead was like feeling the new shoots of spring pushing up against the soles of my feet.

*In July 1871, William Morris walked across Snaefellsnes on Iceland. He observed the scattered rocks at the edge of the field of lava and was reminded of the ‘partly torn down barricades in Paris’.

The Paris Commune had by then been brought to an end. Morris wrote to his wife Jane, saying that he felt the memory of it had become more important while he was in Iceland, while he had barely noticed the events as they had unfolded during the spring. He grew fascinated by Iceland during his stay and said that he found the country ‘lacking all visible aspects of commercialism’. He was delighted finally to see this ‘parallel world’ with his own eyes. Its relevance to the struggles of the communards seemed a natural conclusion.

Morris was aware of being a Romantic. Medieval Iceland was a vision of what might have been, just as the Paris Commune, whose executed activists had only just been dumped into mass-graves, was also a vision – another example of what might have been. Morris called his thought experiment ‘a parable’. A parable is not a story about the past but a way of opening it up, like the door of a tool shed – opening up in order to inspect realistic options for change, and to use the hopes of the past to structure the needs of the present.

The Paris Commune qualified as one of Morris’s parables. He saw it as an ‘exemplary suggestion’, which had turned out to be impossible to realise but nonetheless lived on as a memory, an example and a hope for the future.

*We managed to be late, or maybe we got there just in time. We travelled past towns and villages where slabs of concrete, timber, caved-in roofs, tumble-down fencing and iron railings merged into the grey dough of poverty and longing to see another world. We were in time to spot

The Commander of the Greys, as Andrzej Stasiuk poetically named Communism in his novel

Tales of Galicia, but saw only his back as he turned the corner. He never showed face but it was easy to stay on his trail.

What did we know about real Communism? Nothing. We were attracted to things like the sediment-clogged aquarium and the church without walls. The church without walls was packed with people. Crowded and nestling close together, the congregation’s voices rose in unison – a scene so unlike the empty, tired churches we remembered from where we grew up.

What we were discovering was not Communism but something else, something from long ago. Beneath all these layers, Europe had healed. Once the Wall came down in 1989, what we had been waiting for, either unconsciously or in secret, was returned to us: history itself.

Not the history we had learnt in school and received ticks in the margin for getting right but fractured, desperately sad but somehow enticing stories from a past that threatened us with death, that took human shapes and crawled into bed with the backpacking nineteen-year-old who for the first time was travelling east, via Sassnitz to Budapest.

It seemed in no way possible to travel normally in this revitalised Europe, because its historicity was like a special medium you had to get through. It was a struggle and slowed you down. You had to put up with smells that stuck to your clothes and something gummy underfoot.

Back then, in 1990, when we Swedes packed our bags to go to somewhere in Central Europe, we were wrong to think that our country was a community without history. It was a mistake, even though the sentence ‘We Swedes have no history’ was the national standard introduction. But it is true that we had no experience of historical events forcing us into a corner and retarding, stealing or distorting our lives. Well, that’s what we thought (of course we did have this experience, but in a different way and it took us time to discover this).

*The struggles driving the events of 1989 were constructive. Unlike previous European revolutions, the aim was not to destroy the old but to build something new. A civic community. Many of the leading personalities had in their past expressed a will to create: Václav Havel, Lech Wałęsa, Adam Michnik, Marianne Birthler. The post-socialist transformation turned out to have neither a clear-cut beginning nor a definitive end. Democratisation, privatisation, restoration and expansion of the European Union – we still couldn’t close the door on the past. The grand project of European integration was like a tent with torn canvas forever flapping in the wind.

As one global problem after another started up – financial crises, refugee crises – Europe did not grow more closely integrated. On the contrary, gaps seemed to open up. Towards the end of the 1990s, the future of European integration became the problem. Seen from an aesthetic perspective, the anachronistic realm of eastern and central Europe was worth protecting at any cost. When the Wall fell, a parable had been revealed – a weave of possibilities that ran the risk of being lost in the parallel world of reality. ‘We truly have no idea if [European liberty] entails real freedom,’ Andrzej Stasiuk said in 2002 in an interview with Gazeta Wyborcza. ‘I would not want the liberalism that prevails in Europe to become the next ideology to dominate us all. But for all our reservations, I fear it will come to pass. I would be inconsolable if Europe disappeared into a homogenous mixture in which East and West can no longer be differentiated.’

When what matters is to understand Europe, geography may well be less important than imagination, although they are as intimately linked as madness and common sense – or so Stasiuk wrote. Perhaps Europe is doomed to be an unfinished project? Would it be a fall from grace and a relief? Just an open borderland between real places; between expectations and miscalculations. Forces merging in subterranean waters before finally draining into the sea.

After 1989, the rift between West and East did not cease to be both geographical and moral, as it always was. Nor did East and West cease borrowing from each other and returning the loaned goods worn and dog-eared. In addition, new boundaries were carving deep divides between generations and, by extension, between different ambitions and world views.

*The first time I moved to Berlin was in 1994. For a while, the city was all I had. I lacked many things, including money and proper plans for the future. But then, the rent was next to nothing, I had no sorrows and found plenty to enjoy – and I had as much time as I needed. It was so totally rock-n-roll and so utterly different from my idly bookish and far too expensive years as a student in Stockholm that I shocked even myself.

It offered me a rabbit hole of my own. I had vanished. And I did it when I had hardly got round to realising my need to disappear. Quietly and on a grand scale. I couldn’t possibly have guessed that I’d grow dependent on that rabbit hole. I kept on dashing underground at odd times in order to feed on new impressions. These were years of complete self-fulfilment.

But the longer I stayed in this exemplary suggestion of parallel reality, the more other aspects caught up with me. The armour of anachronism oxidised badly. I acquired memories. And even though I never personally encountered the Commander of the Greys, I heard more about him from my friends. I got my bearings by learning about other people’s pasts. This was a new kind of geopolitics, landscapes different from those I had visited earlier. I had not lived with these things myself. But I could listen to what others told me.

It was during these years that Europe opened up, one vault after another. First Berlin, Prague and Budapest, then L’viv and Kiev, and, after a few war years, Zagreb, Belgrade and Sarajevo.

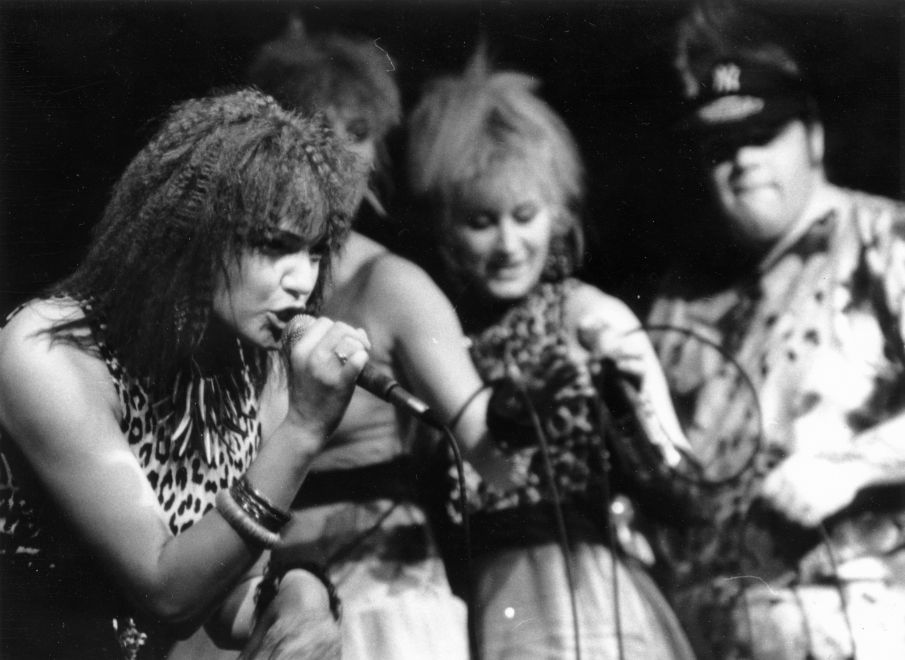

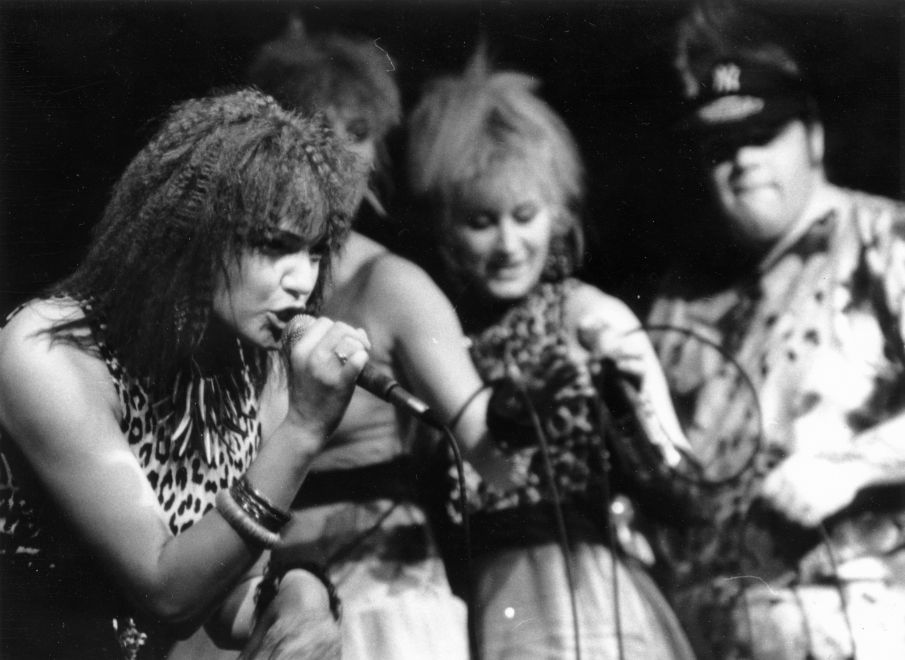

Hungarian punks on stage. Photo by Szigetváry Zsolt on Fortepan.

Once more, the Commander of the Greys managed to get away. By now, this previously elusive if banal character had acquired more distinct features and functions. He might be a teacher or a parent, but also a policeman or a murderer. It was clearer still that there was an explosive difference between having been there and become marked and perhaps ruined – and having arrived too late, in time only to collect a treasure of anachronisms, give indignant speeches and issue invitations to writers’ conferences.

As Dubravka Ugresic wrote in The Ministry of Pain, ‘It will only take a second or two and then, from the same post-Communist shrubbery, a new lot of people will emerge like a walking forest, all armed with their smartly titled doctoral theses’.

I would come across the people, too, in seminar rooms, at conferences, in my office going through their applications: Understanding the Past – Looking Ahead. As Ugresic says: ‘even accidents require management, without it an accident is nothing but a dead loss’.

* In a central scene in Ugresic’s novel, the protagonist, a Croatian literary critic exiled in Amsterdam, watches Philip Kaufman’s film based on Milan Kundera’s

The Unbearable Lightness of Being. In the beginning, she is deeply irritated by its poeticisation of life in Communist Prague. The ‘lives of ordinary Communists’ are cliché ridden and Daniel Day-Lewis looks more Czech than most Czechs. But the illusion abruptly cracks, and the aesthetics of anachronism are no longer able to negate her experience. During the Russian occupation of Prague, Juliette Binoche stares into the muzzle of a gun. Suddenly she is not Juliette Binoche anymore. Instead everything is

authentic. ‘It seemed to me that there, on the screen, they acted out my own intimate history as well’.

Just forget, thought Ugresic’s protagonist. That would allow us to build a new world using what is best of our dreams and our lies. Charity and compassion won’t do. Only forgetting can help. Humiliation and pain will only serve to make us keep remembering.

Forget! Be sure to forget. For the sake of the future and of life.

These are the words of someone who has never sensed the satisfactions of anachronism. Meanwhile, those of us who arrived a little too late, caught only glimpses from behind of the commander or the teacher or the executioner, and could withdraw to the audience seats at any time – for us, to forget sounds threatening. We feel that history is what makes Europe meaningful, that it is the stuff we are made up from and the medium through which we move, even though it slows us down and makes us hesitate.

*I’m spending today with a group of academics from faculties of arts and social sciences. Most of the members of the group grew up in East Germany, the Soviet Union and Poland. Most are about ten years younger than me, at least in number of years on this earth – for surely there are other ways of measuring the length of a life? When the Wall came down they were children. What they can remember seems to burn with a special intensity, their memories are fertile and full of mystique. The big questions when they were young focused on the meaning of freedom, in practical and realistic terms. Is freedom possible? How to become educated? How to train in a society when its values can change so rapidly?

‘You Swedes have never been caught in between, never been stuck on neutral ground’ I was told during one of our evening meals. ‘You have always been above it all. Like angels. Looking down.’

I have also learned that established periodisation may not consider the most important dates of change; that these are negotiable, under constant review. In terms of how people experienced the collapse of the Soviet Union, 1984 might actually be the more significant marker. That was the moment they became post-Soviets. For example, if you were born before 1984, you could join the Young Pioneers at the age of nine, or the pre-pioneers at the age of seven. But if you were born later, by the time you were old enough, that institution was no more. Nor was the state that had founded it and made it work.

Photo by Heather Zabriskie @heatherz on Unsplash.

One of my closest friends, a Russian architect born in 1980, recently recalled to me a scene from her childhood that had stayed in her mind: ‘I remember the day I stopped ironing my Young Pioneer neckerchief. I was 11 years old. Nobody had told me in so many words that something had changed. I must have felt it though. It was suddenly unthinkable to get the iron out, to smooth the folds… how meaningless. Mum scolded me for being lazy. But she called the headmaster a little later and told him that I wouldn’t come to today’s meeting, and that I probably wouldn’t come at all anymore. I recall overhearing her asking silently into the telephone: “What’s the point?”’