The new issue of the Flemish journal ‘rekto:verso’ informs us about historical monsters, monsters in the movies, and monsters at the circus. But it also discusses monsters that aren’t always recognizable as such: the embodiments of monstrousness experienced in multiple ‘Others’.

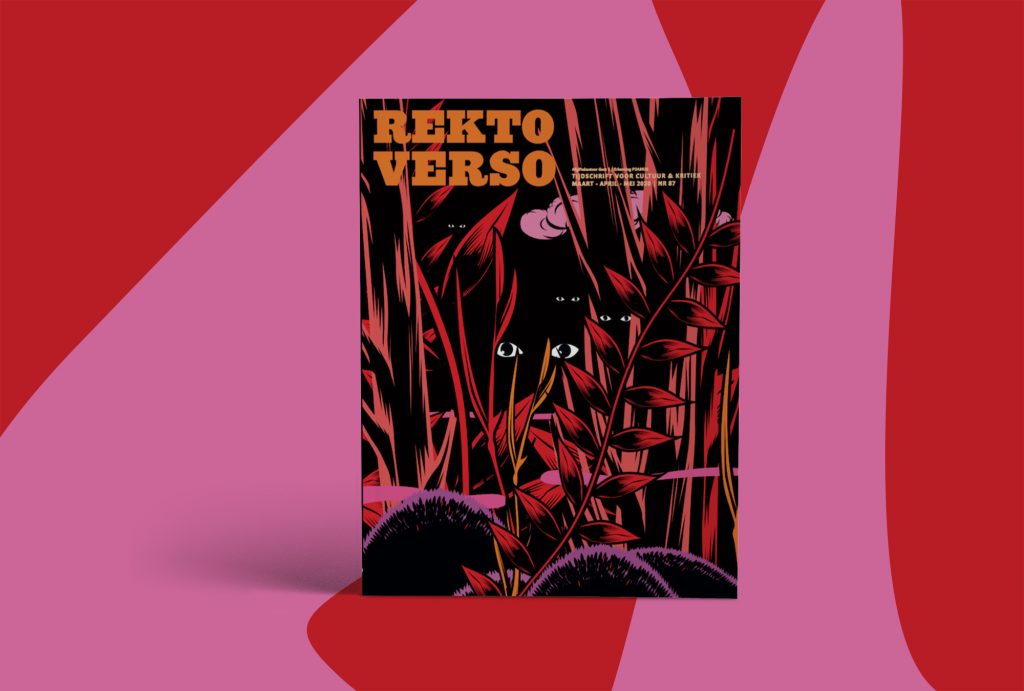

Featuring beautiful if disturbing artwork, the new issue of the Flemish journal rekto:verso informs us about historical monsters, monsters in the movies, and monsters at the circus. But it also discusses monsters that aren’t always recognizable as such: the contemporary embodiments of monstrousness experienced in multiple ‘Others’.

Featuring beautiful if disturbing artwork, the new issue of the Flemish journal rekto:verso informs us about historical monsters, monsters in the movies, and monsters at the circus. But it also discusses monsters that aren’t always recognizable as such: the contemporary embodiments of monstrousness experienced in multiple ‘Others’.

Myth: Ambitious and intelligent women from Hilary Clinton to Greta Thunberg, who ‘dare to transcend the norms and values of patriarchal societies’, are often perceived as monsters. Zeynep Kubat connects their fate to the myth of Medusa. We think of her as ugly and aggressive, but she tells a story about rape culture and how to claim one’s voice. If Medusa is a feminist symbol, then the monstrous might harbour positive energies in the battle for rights and emancipation.

Colonialism: Sibo Kanobana explores the figure of Black Pete in the Dutch-Belgian tradition. There are many similar figures in cultures worldwide, but the Dutch-Belgian ‘monster’ is unusual in being a product of colonial history. Slowly but surely, however, this is changing. ‘Although Black Pete and his significance as an object of hilarity will not disappear, his colonial and imperialistic connotations will’. Monstrous and magical characters are loved and wanted and perform an important cultural function.

AI: Gaea Schoeters sees artificial intelligence as a present-day Frankenstein: ‘Once Pandora’s box is opened, we will not be able to put the monster back.’ AI is also monstrous because it is utterly incomprehensible, even for those who conceived it. However, the real question is less who understands it, but rather who owns it — because whoever does, also owns the world.

More articles from rekto:verso in Eurozine; rekto:verso’s website

This article is part of the 6/2020 Eurozine review. Click here to subscribe to our weekly newsletter, to get updates on reviews and our latest publishing

Published 20 April 2020

Original in English

Contributed by rekto:verso © Eurozine

PDF/PRINTNewsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Related Articles

Perceptions of Chinese tech are changing: ‘Made in China’, once synonymous with cheap, replica production, has morphed into ‘Cool China’, showcasing glamorous hypermodernism. Silicon Valley’s growing reverence for its rivals illustrates the US’s competitive rush and its autocratic turn. But avant-garde Chinese cultural narratives no longer seek to reflect the West.

Truth, trust & tricksters

Index on Censorship 3/2025

How AI is changing the nature of censorship; artificial intelligence versus historical truth; revisiting the UK government’s response to 7/7; missing Palestinians from this year’s Berlin Biennale.