UK journal ‘Index on Censorship’ marks a century of the Chinese Communist Party by questioning China’s concurrent loss of traditional values and lack of interest in CCP propaganda. Also: state TV’s precarious global role in the regulatory spotlight.

The real body beautiful

Vikerkaar 4-5/2021

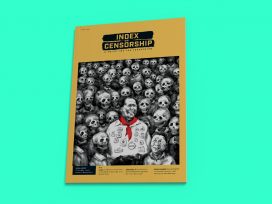

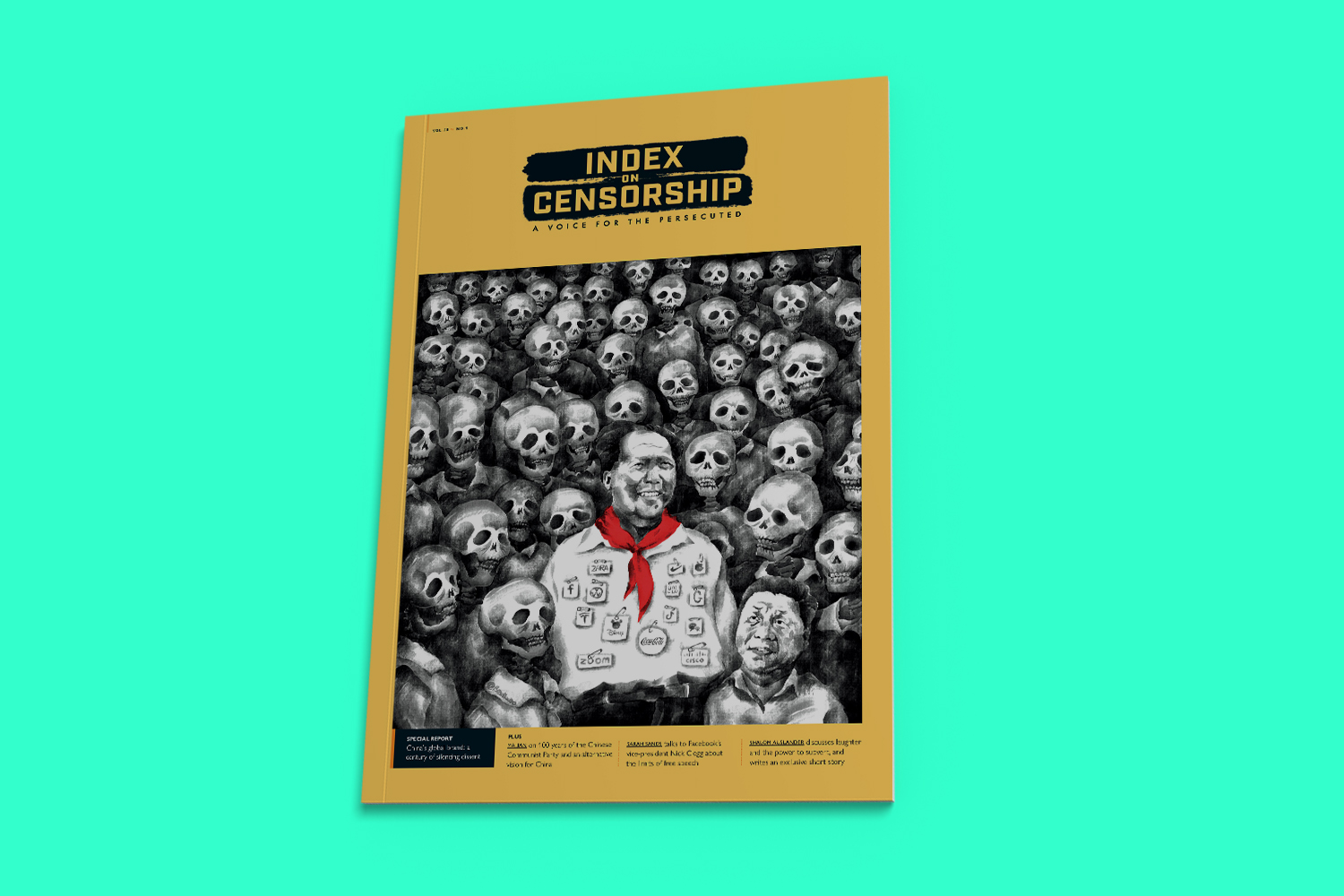

Communism’s centennial abyss

Index on Censorship 1/2021

Understanding money

Czas Kultury 1/21

Subscribe to our weekly newsletter

Marxists from all over China secretly gathered in Shanghai and founded the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) in 1921. The party’s centenary, coming ‘at a moment when the West seems uncertain in its approach to an increasingly confident and aggressive Chinese brand’ is no cause for celebration, argues Index on Censorship’s editor Martin Bright, ‘but it is important to mark it.’

Values

A stranger’s selfless act inspires Ma Jian to reflect on the traditional values of Confucianism – benevolence, righteousness and propriety – which 70 years of CCP rule have challenged. While illusions of liberation initially survived, despite Mao’s Great Leap Forward campaign and consequent Great Chinese Famine, they eventually gave way to the dehumanizing nightmare behind communism’s utopian dream.

Violence, propaganda and lies are the persistent glue that has kept the party in power. But the CCP has also changed to live on by ‘embracing, with increasing vigour, the capitalism Mao strove to eliminate,’ writes Ma Jian. As a result, the Chinese are now richer, but the country has plunged ‘into an ever-deepening moral abyss,’ Jian argues.

Propaganda 2.0

Traditional forms of propaganda no longer appeal to China’s young generation. Therefore, the PCC has transitioned ‘from Maoist formalities and rituals to language that caters to popular audiences,’ exploiting the internet to arouse ‘nationalistic sentiments in an approachable fashion’, writes Tianyu M Fang. The CCP-backed Communist Youth League is the most popular uploader on Bilibili, a video sharing platform, and has gathered 15 million followers on Weibo, the Chinese equivalent of Twitter.

But the government is not the only voice in the Chinese digital environment: ‘media institutions, privately-owned tech firms, cultures, subcultures and a growing number of internet users all contribute to an ever more complex network of forces shaping narratives and discourses,’ Fang writes.

Off air

Last February communications regulator Ofcom revoked CGTN’s one-and-a-half-year-old UK broadcasting licence, stating that the Chinese state channel’s programming is controlled by the CCP. China, in retaliation, banned the BBC World News from its national airwaves. ‘The row has focused attention on the intense competition taking place in global TV news,’ writes Ian Burrell.

State-backed channels such as CGTN, Qatar’s Al Jazeera and Iran’s Press TV have ended the BBC-CNN duopoly in the field, and, as Burrell suggests, ‘regulators have a tough job distinguishing between impartial news and state propaganda, and if they do take punitive action they can be cast as enemies of free speech.’

This article is part of the 10/2021 Eurozine review. Click here to subscribe to our weekly newsletter to get updates on reviews and our latest publishing.

Published 16 June 2021

Original in English

First published by Eurozine

© Eurozine

PDF/PRINTNewsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Related Articles

A changing world

EU, USA, China

From COVID-19 to economic tensions and full-scale war in Ukraine, the relationship between the EU, the US and China has undergone seismic shifts since the last European Parliamentary elections in 2019. This year’s elections on both sides of the Atlantic are likely to alter these dynamics, changing the geopolitical landscape again.

Writing open letters of protest, quoting Václav Havel, led to incarceration for a young Chinese woman. How deep do comparisons between communist China today and Czechoslovakia of the 1970s and 1980s run? And what can Jan Patočka’s thoughts on evading passivity tell us about the compulsion for dissident acts?