Cold panic

- Eurozine Review

4/2017

‘New Eastern Europe’ warns of the de-Europeanization of the Balkans; ‘Mittelweg 36’ prefers transformation over far-Right fossilization; ‘Soundings’ embraces populism; ‘New Humanist’ critiques imaginative humanitarianism; ‘Host’ asks what happened to the Czech literary mainstream; ‘Czas Kultury’ reports on Polish Roma behind walls; ‘Res Publica Nowa’ seeks higher truths; and ‘Glänta’ suffers climate angst.

New Eastern Europe (Poland) 3-4/2017

New Eastern Europe takes a ride on the ‘The Balkan Carousel’. It is not a happy experience. Miljenko Jergović describes the increasingly intolerant tone of politics in Croatia, the EU’s newest member, where ‘the process of … de-Europeanization is shocking, all-embracing and radical.’ He explains that ‘anti-fascism, in recent years, has become a dirty word. When someone is described as an anti-fascist, for instance, it usually comes with the suggestion that they are also an enemy of Croatia.’ His survey of the current political situation across the former Yugoslav space concludes with a bleak warning: ‘The nations of the Western Balkans are readying themselves for a war similar to the ones that began in 1914 and 1941.’ He urges Europe to re-engage.

Radicalization: Tatyana Dronzina and Sulejman Muça highlight the growing problem of Islamist radicalization in the region. Bosnia and Herzegovina is a particular cause for concern. ‘Despite the fact that only four per cent of [Bosnian Muslims] adhere to radical views, it increasingly seems that the country is becoming a sanctuary for ISIS fighters, planners and recruiters,’ they warn. Reports proliferate of ‘Sharia villages’, where ‘most families live in polygamy under Islamic law, and symbols of ISIS are freely displayed in public places in breach of the established constitutional order’. Their remote locations, and Bosnia’s mosaic of administrative structures hinder police control of such places. Meanwhile, Kosovo and Macedonia have also acted as sources for ISIS recruitment.

Ukraine: Some consolation arrives from an unlikely source: Kramatorsk, a monotown near the front line of the conflict in eastern Ukraine. There, Paulina Siegień has been talking to Alexander Tanchuk, a former policeman who now ministers to the Orthodox faithful and the families of fallen soldiers. Tanchuk, a native Russian-speaker, explains his decision to join the Kyiv Patriarchate rather than its Moscow counterpart, hinting at the complex relationship between them, and the influence of Russian propaganda: ‘We are presented as fascist, schismatic and Russia-haters.’ Despite these tensions, the ever-present war and the local bureaucracy, he succeeds in launching the construction of a new church – and in maintaining a sense of hope.

More articles from New Eastern Europe in Eurozine; New Eastern Europe’s website

Mittelweg 36 (Germany) 2/2017

In 2016, a year after her famous ‘We can do this’, Angela Merkel assured voters that ‘Germany will remain Germany’. This may have made sense politically, given the far-Right backlash to the refugee crisis. But it was sociologically naive, write the editors of an issue of Mittelweg 36 on multiculturalism. Political measures, as far as they go, have been based on the diffuse notion of a ‘lead culture’. Yet the failure of assimilation policy in connection with the Gastarbeiter is all too well documented. What is needed now is a sociology with ‘vision’ and ‘perspective’.

Transformation not fossilization: The far-Right, writes Hartmut Rosa, has a ‘fossilized relationship with the world’. Its supporters are motived by the conviction that ‘This is our country. We want to be who we are and stay that way. We understand our homeland to be the embodiment of the idea that nothing can or should change.’ They ‘lack the experience of being in control of their own destiny that would allow them to engage in open and active dialogue with the unfamiliar – a dialogue that would then even enable them to incorporate these new experiences in a self-transformative way.’

Refugees, argues Rosa, ‘represent possibly our last great chance to overcome disaffection, escape the current state of inertia and rejuvenate our society. For refugees have the potential to soften those very structures that have become sclerotic. They offer us a voice that embodies something unfamiliar, something different, that can make us rediscover our own voice, express it and, by listening to and reacting to one another, transform ourselves.’

Multiculturalism in the US: The problem in the USA is not that multiculturalism has failed, argues Volker M. Heins, but that its success in detaching privilege from skin colour and gender has created ‘a hyper-pluralistic society of minorities, in which it has once more become possible to mobilize the fiction of a native majority’.

More articles from Mittelweg 36 in Eurozine; Mittelweg 36 website

Soundings (UK) 65 (2017)

‘Populism is a legitimate political discourse – not an outsider phenomenon to be ejected from the mainstream’, propose the editors of Soundings in their introduction to an issue on ‘populism and alliances’. According to contributor Paolo Gerbaudo, the ‘pejorative view’ of populism ‘seems of little use at a time when, far from being a marginal anomaly, populism seems set to become the hegemonic political logic.’ The future, Gerbaudo argues, lies in embracing a populism based on popular sovereignty. This is ‘the discursive and political battleground which will determine whether the contest for hegemony in the post-neoliberal era will take a progressive or regressive direction.’

Trumpism: Matt Seaton sees Trump as the apogee of a negative form of collectivism emerging regularly throughout US history. ‘Donald Trump has succeeded in articulating the legitimate sense of grievance of a great struggling class of people to a deeply reactionary identity politics, by drawing on their folkloric sense of the American dream as their lost birthright. If the United States is to survive this outbreak of the virus of populism – the most dangerous in its history – the Trump resistance must find ways to detach white nationalism from Trumpism’s false promise of economic justice.’

Political writing: As Britain focuses on Westminster, the writings of cultural theorist Stuart Hall serve to warn against ‘the reduction of politics to its technological and institutional practices and to its attendant discursive forms: the absolutism of opinion polls, for example, or of the more elaborate intellectual apparatus of psephology.’ Hall ‘was very critical of the orthodoxy that presents itself, sotto voce, as the reasonable, sensible acknowledgement of how, certainly in Britain, politics just is,’ write the editors of a recent collection of Hall’s essays. ‘For Stuart, in contrast, the fundamental fault-line was not so much between Conservative and Labour, but between a politics that was constrained by the norms of Westminster and one capable of embracing the breadth and complexities of human life as it was lived day by day.’

More articles from Soundings in Eurozine; Soundings’ website

New Humanist (UK) Summer 2017

The notion that fiction is a force for moral good derives from the age of revolution. But imaginative empathy does not always translate into egalitarian politics, writes literary historian Lyndsey Stonebridge in New Humanist. ‘Recent studies back up the claim that reading fiction makes us more empathetic, and for good reason. … What remains a puzzle is how we might get from imagining other people to agreeing to share resources and power with them.’

The real question today, Stonebridge argues, is not ‘how we can generate more generous imagining in the world, but why we tell ourselves that reading is going to redistribute human rights. What do we want our books to do that we cannot?’ Given the proven limitations of imaginative humanitarianism, a better starting point for the ‘human rights project now’ may be Samuel Beckett’s more modest dictum: ‘Ever tried. Ever failed. No matter. Try Again. Fail again.’

Phoney morality: Alev Scott hears echoes of history along the ‘misleadingly tranquil coastline’ between Turkey and Greece. She compares the journeys of today’s Middle Eastern refugees with those of Christians and Muslims ‘exchanged’ between Greece and Turkey in 1923, and talks to Turks in the coastal town of Ayvalık who continue to speak a dialect of Greek. Meanwhile, resentment on the Greek island of Lesbos at the effects of the crisis on tourism is tempered by the knowledge that Greek families there were once refugees too.

But politics is working against these subtle understandings. While the ‘infamous population exchange of 1923 was at least partly conducted in a constructive spirit,’ the current deal to stop migrants is characterized by what many people see as ‘phoney morality’. Scott’s surprising conclusion is that ‘the forced exchanges of the past – contrived and crazy though we now consider them – were in many ways more humane, and logical, than the deportations of today’.

More articles from New Humanist in Eurozine; New Humanist’s website

Host (Czech Republic) 5/2017

This month’s Host features an interview with Jáchym Topol on his latest novel, A Sensitive Man (Citlivý člověk). Topol describes the deaths of his father, mother and brother – ‘those grotesquely dark situations around dying’ – as his inspiration for the book, which took him five years to complete. He compares his writing style to ‘a beaver – I cut down a tree and then gnaw it into matchsticks’. While interviewer Ondřej Nezbeda finds the novel ‘without hope,’ Topol objects that he ‘laughed a lot while writing it’ and insists that the hope and humour in his novel outweigh the horror. He finds little to laugh at in the current Czech political scene, however, describing president Miloš Zeman as ‘unbelievably vulgar, unbelievably awful … an eruption of blatant Czechness.’

Absent mainstream: Reporting on the ‘mainstream’ in contemporary Czech literature, Eva Klíčová explains the situation after November 1989, when ‘literature was finally ‘liberated’ from politics, society, all kinds of duties … and finally even from the reader.’ She states her ‘long-time conviction that in literature we need a central, i.e. mainstream or second floor (between the ground floor of trash and the elitist experiments at the peak of the literary hierarchy’s imaginary pyramid).’ She discusses the subject with several theorists, including Pavel Kořínek of the Institute for Czech Literature, who states that a ‘quality mainstream’ is also missing in Czech comics.

Literary biography: František Ryčl reviews Reiner Stach’s biography Kafka: The Early Years. He praises the volume for its ‘appealing, reader-friendly form’ (as well as Vratislav Slezák’s ‘readable, fluent translation’) but disagrees with Stach’s ‘harsh and censorious approach to Max Brod’, Kafka’s friend and later editor.

More articles from Host in Eurozine; Host‘s website

Czas Kultury (Poland) 4/2017

In an issue of Czas Kultury on ‘Roma behind walls’, Emilie Kledzik and Katarzyna Czarnota look at the emergence of urban Roma camps on the outskirts of Polish cities. Their inhabitants came mainly from Romania in the late 1980s and early 1990s and today still live divided off from the rest of the population. ‘These walls will not fall anytime soon, but images from beyond them remain in memory’, as the editors put it.

The images contained in this issue are indeed memorable. Kledzik and Czarnota reveal not only of the exclusion but also the violence that this marginalized group face daily. However the richness and originality of artistic works by Polish Roma are also striking. The editors have chosen to include interviews with artists whose work ‘contributes to the rapprochement between the majority population and the Roma minority’. Adding other perspective, Karolina Wróbel looks at the co-existence of Roma and Jews in the Warsaw Ghetto, and Malgorzata Dambek reports on teachers working with Roma children in Slovenia.

Also: Bulgarian philosopher Alexander Kiossev introduces a section on ‘self-colonization’ in Polish history, politics and literature.

More articles from Czas Kultury in Eurozine; Czas Kultury’s website

Res Publica Nowa (Poland) 1/2017

Res Publica Nowa asks how we arrived at a world where feelings influence public opinion more than facts and truth surrenders to lies. The conclusion: post-truth is not a new phenomenon but more a case of the emperor’s new clothes. The task is to muster up the courage to state that the exponents of post-truth are naked.

Higher truths: Contributing to post-truth are, among other things, the collapse of the educational system and decline of traditional media. In interview with Agnieszka Rosner, writer Paweł Potoroczyn – head of the Adam Mickiewicz Institute before being dismissed by the current government – asserts that truth needs the support of a strong community capable of negotiation but also conscious of absolute truth. ‘We are all aware of its existence,’ says Potoroczyn, ‘because we know perfectly well when we lie’.

Post-truth: Krzysztof Pacewicz presents a short history of truth in modernity, from the fall of great narratives and the end of the idea of modernization to individualism and post-modernism. Liberals, he argues, have forgotten that truth binds a community together, which is something that GDP cannot do. Dollars replaced values expressed in words, thereby allowing the truth of money to replace conceptual truth. Post-truth is a logical consequence of the deficit of truth in late modernity.

Positivism: The ‘cult of fact’ in politics – reports, statistics, chronologies – underestimates the significance of values, writes Patrycja Sasnal. Looking at international relations, she argues that responsibility depends not only knowledge but also on belief.

More articles from Res Publica Nowa in Eurozine; Res Publica Nowa‘s website

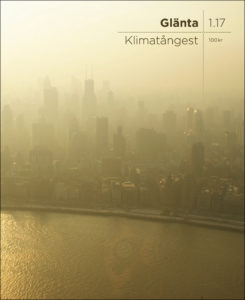

Glänta (Sweden) 1/2017

As if we weren’t scared enough already, Glänta’s new issue on ‘Climate Angst’ appears just as Donald Trump announces that the US is pulling out of the Paris climate accord.

Julia Nordblad, a historian of ideas, has guest-edited the issue. In a candid yet canny essay, she remembers the stickers all over Paris during the climate summit in 2015: ‘We are nature defending itself’, they read. But are we really defending ourselves? ‘We are nature driving SUVs and building pig factories. We are nature flying to the other side of the globe to attend a climate conference, getting all anxious about it. We are nature tearing itself apart – and knowing it. Why don’t we defend ourselves?’

We stick to the liberal principle that says that as long as my actions don’t hurt others, it’s up to me to decide what I do. ‘But that principle wilts in a world warming up,’ writes Nordblad. How much longer will the question whether I choose to carpool or to drive alone to work in my SUV remain a private one?’

Cold panic: In two updated chapters from her 2013 book In Catastrophic Times, Belgian philosopher Isabelle Stengers describes an historic moment – the present – in which ‘we’ don’t know in whose name ‘we’ should and can act. ‘Our guardians are responsible for the management of what one might call cold panic, panic signalled by the fact that we accept openly contradictory messages: “keep consuming, economic growth depends on it” but “think about your carbon footprint”; “you have to realize that our lifestyles will have to change” but “don’t forget that we are engaged in a competition on which our prosperity depends”. This panic is also shared by our guardians. Somewhere they hope that a miracle might save us – which also signifies that only a miracle can save us.’

Also: Paintings by Anna-Lisa Unkuri, poems by Sara Granér and Naima Chahboun, and poetry-statistics by Jonas Gren: ‘The majority of crying minors / are consoled by glaciers’.

More articles from Glänta in Eurozine; Glänta’s website

The Eurozine Review presents a selection of the latest issues of Eurozine partner journals, summarizing their contents in English as a way of encouraging cultural and political dialogue between national public spheres in Europe.

Published 9 June 2017

Original in English

Newsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.