Farewell to Arena from a former editor

A common friend in the ‘Republic of Letters’ has passed away. Or, in the terminology of Hinduism, it has transmigrated itself into a new reincarnation. Eurozine’s Swedish partner Arena has published its last print edition. Its future will be digital, in some form. But this is a landmark. If even Arena cannot survive in print, asks former editor Olav Fumarola Unsgaard, can anybody?

It was 1993, in a small freelance office off the beaten track in the Södermalm neighbourhood of Stockholm. An idea formed. To start a magazine – but even more ambitious. The founding editors Håkan A Bengtsson and Per Wirtén wanted to transform public debate, especially within the left. Sweden, and especially the Swedish left was back then very ‘male, pale and stale’. Each part of the left – liberals, social democrats, academics and anarchists – kept to themselves. The idea of Arena was to be the common denominator. A forum for debate, but with a very distinct voice of its own.

The last issue of Arena is based around a wide-ranging interview with Per Wirtén. He is a dedicated European, with a keen eye on feminism and postmodernism. That combination made him, in the early years, a party of his own. Håkan A Bengtsson, for his part, is the most dedicated reformist around: both of his beloved Social Democratic party, but also politics in general. Maybe he is too intellectual for the daily back-and-forth of politics, but sometimes also the other way around. The unique combination of Håkan and Per created Arena. The ‘team photo’ of the first editorial board confirms that. Even today they look like a rare mixture of leading academics, poets and politicians. The mix had not been seen before, nor was it seen again in the context of Swedish publishing.

A couple of good ideas are necessary to form a cultural journal, but other skills are also needed to publish 140 issues over a period of 24 years. With the journal as the core, over the years it spawned a small conglomerate: a think tank, publishing house, a PR agency, a web-based daily, and so on. Håkan and Per was the editors for many years, but passed the torch onwards. To Kristina Hultman, Magnus Linton, Karolina Ramqvist, Devrim Mavi, myself, Malena Rydell, Mikael Feldbaum, Klas Ekman and Björn Werner. Strangely enough the journal didn’t change that much. It was still at the centre of debate. An eye-opener for many, but also hated. ‘Not true left’ was the phrase most commonly used.

Among the issues Arena was very quick to introduce were third-wave feminism, post-colonialism, intersectionality and crip theory. It also changed the perception of Swedish anti-drug policy from ‘successful’ to ‘inhumane’. But maybe its greatest impact was the (then) radical idea that Sweden is part of Europe and should be part of both the EU and the euro. In text after text, Arena cut Swedish isolationism to pieces. And, of course, in the meantime Arena became a partner of Eurozine.

So why is Arena closing down? I don’t know the specific details, but we live in turbulent times. In 2014 the cross-platform measurement company comScore Inc. released a report entitled ‘Digital Future in Focus’. It said, among other things: ‘The most disruptive shift in the digital media marketplace has been the shift from desktop to mobile platforms. This is evidenced by the fact that smartphones were introduced several years ago, and these devices, now along with tablets, continue to drastically alter the dynamics of consumer behaviour,’ while warning: ‘Publishers and media companies may view the multi-platform shift somewhat ambivalently, given its potential to disrupt established business models.’ (pp. 7 and 8). To put things in historical context, the shift from paper to smartphone/tablet is the fastest and most radical change in reading behaviour in the history of mankind.

Both within the national circles of cultural journals and in the European context, Arena was something else. The journal looks more like a glossy magazine than an introverted cultural journal. It has more advertising as well: from unions, but also from large corporations like Microsoft. And, when I was editor, from a cheap brand of box wine with monkeys as its logo. The advertising caused much commotion, but it also helped with the finances. In the Eurozine family, advertising from outside the cultural and literary sphere is relatively rare. Now, as advertising money moves from paper to digital, those journals that are more dependent on this kind of support are the most affected.

Last but not least, Arena was aiming at a broader audience than the traditional cultural journal. If we look at Swedish cultural journals, they are in almost all cases smaller than Arena. They have fewer staff, smaller offices and pay lower fees to contributing writers. All magazines of the size and quality of Arena in Sweden have failed. The social liberal Moderna tider lasted 9 years. Arena’s right-wing nemesis Neo tried, but failed after about 10 years. By comparison, Arena outlived them all, by far. A journal has to be either smaller or bigger. Arena was ‘a medium-size dog with big-dog attitude’ as a famous Swedish/US saying has it. It lasted 24 years.

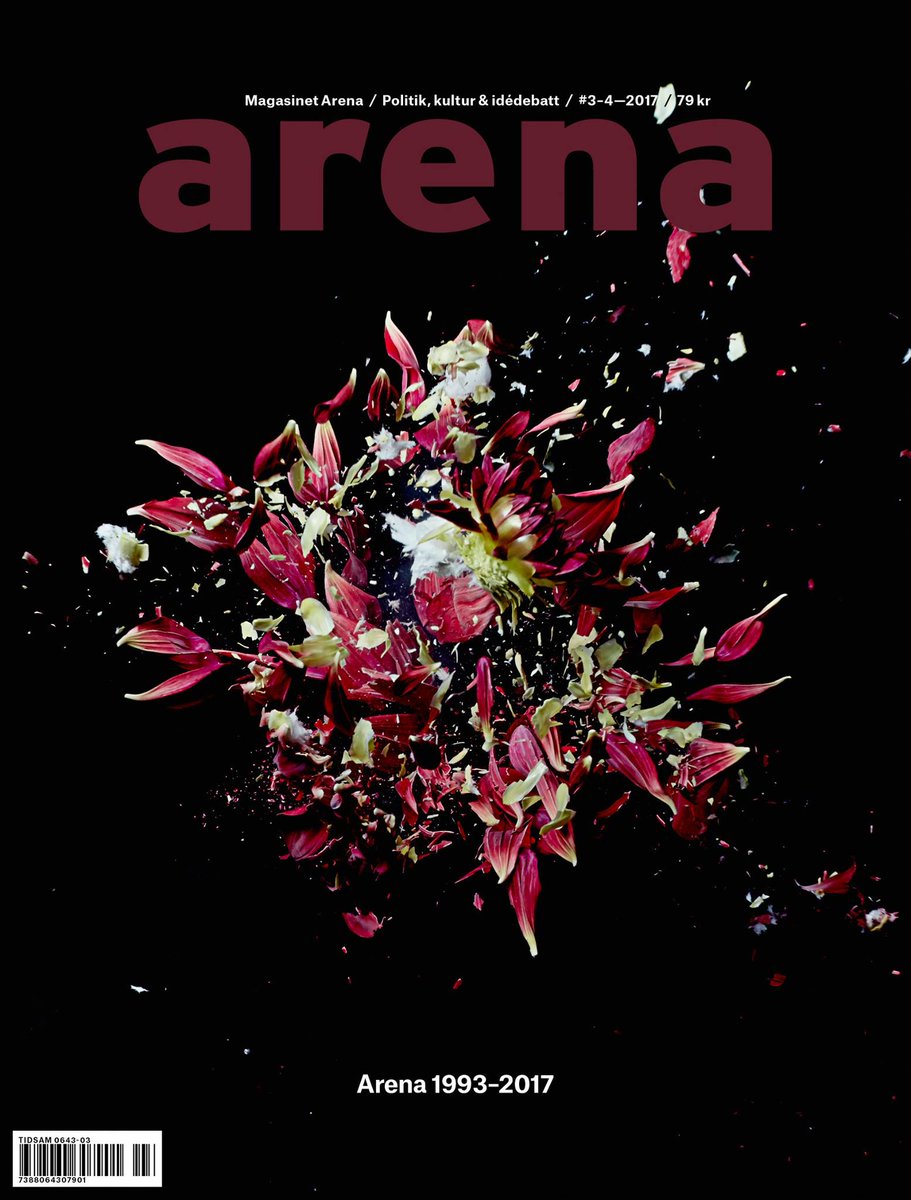

The magazine goes out with a bang – literally. The cover of the last edition shows an exploding bouquet of flowers, in white, pink and many shades of red. The issue is somewhere between a sigh of nostalgia and cookbook for future editors. Hopefully it will inspire a new generation of publishers. Assuming they are out there, it will most likely be in a rundown garage, somewhere off the beaten track…

Olav Fumarola Unsgaard

Former editor of Arena