Chernivtsi palimpsest

The many names of Chernivtsi in Ukraine attest to the tumultuous military and political history of Europe, borne out in cultural and linguistic competition, conflict and compromise in literature, music and art. What traces of this past can still be seen in the city today?

Open any encyclopaedia article about Chernivtsi, and one of the first things you’ll encounter is a list of the city’s names in half a dozen different languages: German, Yiddish, Ukrainian, Russian, Romanian, Polish, Hungarian. This bears witness to the tumultuous military and political history of Europe, borne out in cultural and linguistic competition, conflict and compromise in literature, music and art. Each new set of authorities took pains to erase, to efface the previous version of the city’s history and culture. The Czernowitz-born poet Rose Ausländer, a classic of twentieth-century Austro-German literature, once compared the city to a mirror carp in pepper aspic, silent in five languages.

Tombstones at the Jewish cemetery of Chernovtsy. Photo by Julian Nyča via Wikimedia Commons

It is a striking image. I was lucky: I grew up in Chernovtsy and heard the voice of the carp. As a six year old, with my mother at the central market, I heard these extraordinary conversations in a mixture of Yiddish and the Hutzul dialect. Jewish ladies haggled with Hutzul peasant women. They understood each other perfectly.

The wireless opened up the Romanian world to me in childhood, because Romanian radio could be heard clearly in Chernovtsy. I lived on Lermontov Street (now Kokhanovsky) and can remember what a huge event it was when our neighbours were visited by their Romanian relatives. Among them was an enchanting little girl, Marina from Bucharest. She wore a pink chiffon dress, something none of us had ever seen before. Just one meridian westward, but this one meridian still made itself felt in everything, including a little girl’s dress.

As a schoolboy I was aware of the prison palimpsest, though I didn’t know that word. I mean prison not in an abstract but a literal sense. In my day the square where it was located, next to a secondary school, was called Sovietskaya; now it’s Sobornaya. At one time it was Kriminalnaya and at another Avstria-platz. What strata of doggerel, curses, obscenities and oaths were layered on the walls of the cells of that prison, built in the first third of the nineteenth century! A polyglot palimpsest, as befits Chernovtsy.

In my teens, I adored cinema and worked as a poster artist’s assistant. Truly, of all the artists in the world I loved the inspired daubers of our provincial cinemas best: they, the daubers, had their own hierarchy, their lucky apprentices. Today this craft, this guild, is extinct: print has displaced the freshly coloured poster. And yet here was a genre that knew its own Giottos, its own Chagalls. This was a poster palimpsest.

When I became a student, I discovered life’s meaning in poetry, in literature. Maybe the city had bewitched me, spoken to me in a literal sense. My city has the reputation of being a cultural crossroads. Between the two world wars, its inhabitants included writers who were later recognised as some of the most significant figures of German literature of the second half of the twentieth century. Gifted scientists, musicians, engineers were born and lived here. Why, how did it become such a confluence of cultures; why was it here that German, Jewish, Romanian, Ukrainian poetry peered at, hearkened to each other?

It was Tomsk that helped me unlock the secret of Chernovtsy. Twenty-five years ago, the radio station that employed me at the time sent me on a trip to Siberia, and I set foot in Tomsk for the first time. I liked the city very much. Local historians told me the city owed its architecture to the Poles, among them political exiles. Former inmates of the Gulag, not least my fellow-citizens from Chernovtsy, made a major contribution to the city’s schools, science and music. During the Brezhnev years of stagnation the city had been semi-closed, and Tomsk’s Jews were long denied exit visas, which meant they had, willy-nilly, been forced to maintain high academic and cultural standards.

But what does this have to do with Chernovtsy, and what is this secret I am talking about? Why here? What is the source of this magical chemistry? I think I have the answer. I know who these chemists were.

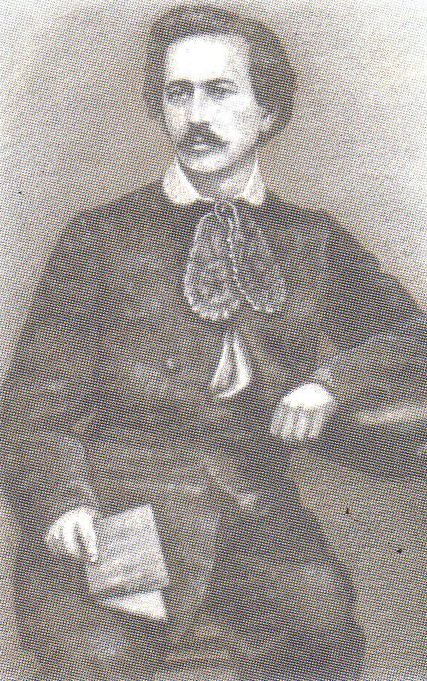

In the mid-nineteenth century, the Austro-Hungarian Empire was shaken by a democratic revolution, which ended in its dissolution in 1918. Repression followed: shootings, arrests, officers reduced to the ranks. Ernst Neubauer, a young revolutionary who had been a journalist for the Wiener Zeitung, was fortunate: he was exiled to the eastern frontier of the Empire, to Chernovtsy.

Ernst Neubauer, c. 1880. Image via Wikimedia Commons

At that time, the brilliant Viennese intellectual and his companions would have felt Bukovina was something like Kolyma. Neubauer was not stripped of his civil rights there. He taught literature and history at the Gymnasium. His pupils included the poet Mihai Eminescu, who was to become a classic of Romanian verse, and Karl Emil Frantzos, a popular German-speaking Jewish author and essayist. The Ukrainian writer and folklorist Yury Fedkovich came under Neubauer’s influence, and would subsequently dedicate a book of German-language poems written to him. Neubauer started a German-language newspaper, Bukowina, with a Sunday supplement in which he published local writers and poets. He wrote books and was the heart and soul of a number of cultural unions.

In the autumn of 2021, I spent a month in Vienna. I wrote poems and essays, wandered through the city, listened to the music of the buildings, stables and palaces, gazed at the paintings of Schiele, Modigliani and Titian, chatted with Viennese colleagues. If I ever brought up Neubauer’s name in discussions with these colleagues, they looked at me blankly. He has been forgotten in Chernovtsy, too. The humus of culture has a life of its own, though probably one best left to specialists in soil fertility.

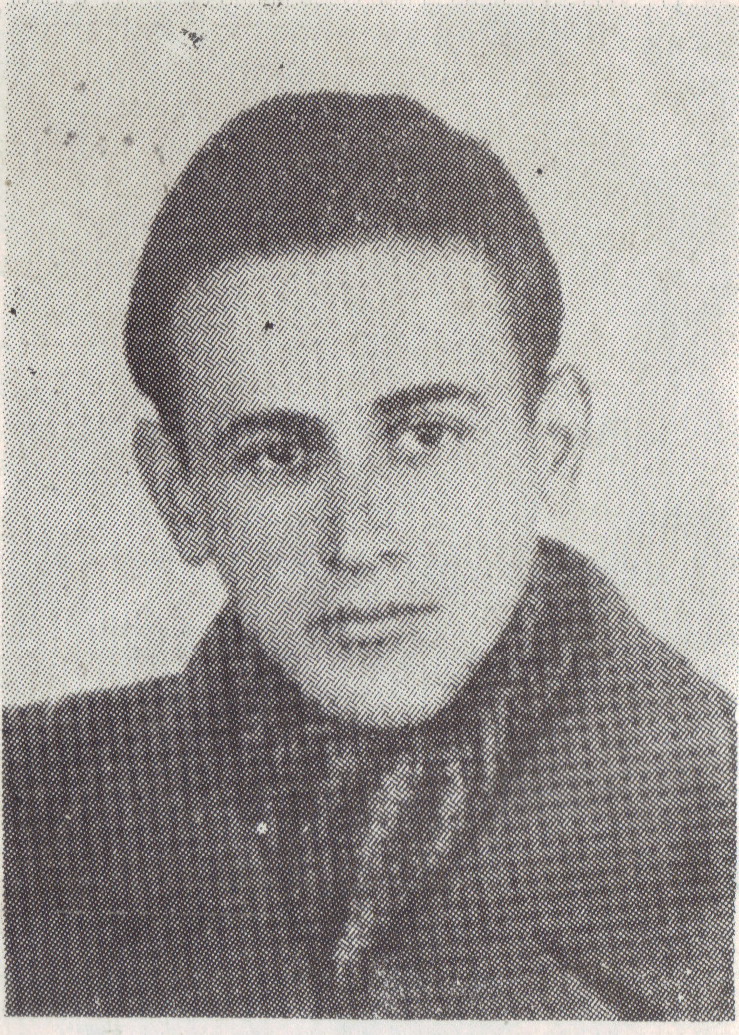

I left Chernovtsy a long time ago, though I go back every year in September for the Meridian Czernowitz poetry festival. The festival has its own talisman, its shibboleth, Paul Celan – born 1920 in Czernowitz, died 1970 in Paris. What I like in Celan’s poetry are the pauses and caesuras. His syntax. He experienced the deaths of his mother and father in a Romanian camp, and was himself incarcerated. That, I believe, is when his heart stopped. For Celan, the caesuras and pauses between words, between grammatical constructions, are not an avant-garde affectation; they are the pauses between heart beats. Another reason why I am grateful to Celan: he was an invisible poet, a ghost poet. Ramshackle Vitebsk is all Chagall. Every step in Dublin brings you up against Joyce. You never hear laboured breathing in Celan, not even in his most tragic poems. He left no baggage behind him in Chernovtsy (Czernowitz), no heavy furniture, no patches of sweat or bloodstains.

Paul Celan, Jewish Romanian-born German-language poet, Holocaust survivor, Czernowitz, 1941. Photo via Wikimedia Commons

The phrase ‘to swallow your tongue’ exists in many languages. It can sometimes be taken almost literally. During the war, it seems Paul Celan swallowed his tongue, from horror, despair, helplessness: he had lost everyone and everything. And later in his poetry he is looking for his swallowed tongue, to let it take its proper place in the cavity of his mouth. This search is the meaning of his poetry. To this day Celan’s quiet voice can be heard distinctly in the acoustic palimpsest of Chernovtsy.

Published 18 May 2022

Original in Russian

Translated by

Frank Williams

First published by Eurozine (English version)

Contributed by Institute for Human Sciences (IWM) © Igor Pomerantsev / Institute for Human Sciences (IWM) / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTIn collaboration with

In focal points

Newsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Related Articles

As capital consolidates, culture recedes, funding vanishes, access narrows. The question persists: why fund culture at all? Cultural managers from Austria, Hungary and Serbia discuss.

Russian drones entering Polish airspace, militarily seen as intensified provocation rather than open warfare, have nevertheless provoked costly responses – both from NATO’s air defence systems and civilian reactions to disinformation. A war correspondent’s view of what can be done technologically – for greater military efficiency and improved civil defence.