A fire is burning in the centre of Bucharest. Twelve hectares of trees and vegetation are under ongoing destruction, threatened with being wiped off the city map. The damage is occurring in Alexandru Ioan Cuza Park, locally known as IOR, a 50-year-old park with a complex history. It is the only place that burns constantly in Bucharest, whatever the season.

Two opposing camps have formed over the park’s transformation. While civil society actors are campaigning for it to be recognized as a public space, public authorities and institutions alongside urban developers seem to have a different agenda. A lack of official accountability and systematic law enforcement is blocking rather than supporting the concerns of local citizens. Behind the scenes of the city’s day-to-day life, its streets, houses, trees and traffic, a wide-ranging conflict is unfolding on many levels between citizens and landowners, tenants and the state.

The park’s emergency reveals a complicated story intertwining unresolved trauma from recent communist history (related to conflicts over litigious property rights), corruption within public institutions, unregulated urban development and poorly implemented environmental policies. The impact of illegal deforestation in this natural setting points to an issue that is commonly overlooked: the importance of green urban space.

Tracing ownership

The degradation of IOR park as a public entity began long before the fires started. Since the fall of communism in 1989, Eastern Europe has been confronting issues related to the politics of memory. Questions about how recent history is recorded and communicated to the public – what is being told and what is being hidden – have arisen. Throughout the region, countries have adopted different methods to deal with this, including financial and symbolic rewards for individuals persecuted for their political stance, judicial rehabilitation of political prisoners, rewriting history books and redesigning museums.

An important aspect of democratization was the restitution of property that had been assumed during communism. The general public, especially those who had been wronged, saw it as atonement for past sins and an assumption of responsibility on their behalf. Romania’s parliament introduced Law 10/2001, which addressed the legal status of real estate that had been taken over by the communist regime between 6 March 1945 and 22 December 1989. While the law enabled Bucharest’s property restitution, the poor way it was applied still haunts Romanian society and the city’s fate today.

IOR Park fire, Bucharest, Romania. Image via Facebook group ‘aici a fost o pădure/aici ar putea fi o pădure’

The section of IOR park that is frequently ablaze is subject to this specific circumstance. Tracing the history of the park located in the Titan neighbourhood, District 3, at the heart of the capital, reveals that at the turn of the twentieth century the site was part of a vast estate owned by I.B. Grueff, a Bulgarian landowner, who bid for the land at an auction in 1903. At the time, Grueff owned the equivalent of almost every part of the Titan neighbourhood and the entire district. Political changes in Romania shifted the estate’s course: the nationalization process brought much of Grueff’s wealth under communist state control in 1945.

The Titan neighbourhood was one of Bucharest’s largest working-class areas. In the 1960s architects inspired by Le Corbusier developed spacious city planning ideas, including a vast park intended to connect people. The park, once completed in 1970, was named IOR, an acronym taken from the name of the nearby factory Întreprinderea Optică Română (Romanian Optical Enterprise). The factory, which produced a wide range of optical products such as glasses, cameras and telescopes, was a symbol of local industrial prowess. After the fall of communism, the park’s name was changed to Alexandru Ioan Cuza, but people continue to refer to it affectionately as IOR.

In the 1990s the entire park was still listed in urban planning documents as a public space. Then, in 2005 Grueff’s nephew, who was his legal heir, ceded part of the parkland and its disputed ownership rights to Maria Cocoru, a woman in her eighties, whose claim to the land remains mysterious. At this point, Bucharest City Hall retroceded the IOR land to Cocoru under Law 10/2001, where its legal status changed from public to private property. Cocoru’s name appears not only as an owner of this disputed area of the park but also of several other green spaces in Bucharest, including Constantin Brâncuși park, named after the famous Romanian sculptor, a 1,431-square-metres park. Brâncuși park has been lying in disrepair for about five years and is no longer in use – it has been abandoned.

Firefighter working the IOR park. Video via Facebook ‘ISU București-Ilfov’

Planning category corruption

Dan Trifu, leader of the EcoCivica Foundation and a specialist in green spaces legislation and urban planning, traces the history of Romanian urban green space privatization to 2000. ‘When the General Urban Plan of Bucharest (PUG) was designed, many green areas and parks in Bucharest were listed in the document as buildable areas, meaning that potential construction projects were allowed there, even though those areas should have been categorized under the usual code used for green areas or parks. The 12 hectares of the IOR were listed in the PUG

under the CB3 code’ which ‘allows the local authority to develop building projects such as administrative, cultural and social institutions in the area’, says Trifu.

The EcoCivica Foundation has filed dozens of lawsuits mainly over retroceded green spaces in the city, dealing with what Trifu describes as ‘the real-estate mafia that has taken over chunks of the city’. Trifu points to the connection between investors and politicians who benefit from common profit-led real estate interests. In some cases investors even begin as party members or collaborate directly with them. Sections of land from almost all of Bucharest’s parks are registered under PUGs codes that enable construction. Green areas between blocks of flats and squares have already been redeveloped.

Parks have either disappeared due to construction interests or have been abandoned. According to local media, 609 hectares of Băneasa Forest – the largest green space within Bucharest’s administrative area – have been retroceded. The names of politicians and business people have been associated with construction in the forest. The woodland’s integrity is increasingly under threat from the expansion of residential neighbourhoods, illegal logging, poaching and fragmentation.

This situation reflects a broader pattern of poorly managed societal order post-communism, where private interests often prevail over public interests and quality of life. According to the investigative publication RiseProject, the grey market of litigious property rights competes with the black market of drugs in terms of profit generated. The phenomenon is known locally as ‘the mafia of retroceded land’.

Making a case for public space

It took around eight years before the majority of local visitors to IOR Park realized that 12 hectares of the space they consider their treasured park were no longer public. People continued to go there because they felt that the place belonged to them, that it was part of their history, of their collective memory, spanning generations. Some partly grew up or raised their children there.

Maria’s daughter, IOR Park. Image courtesy of interviewee

Maria, a 68-year-old woman who has lived in the neighbourhood since it was built, remembers with nostalgia the special times she and her daughter spent walking the paths that have been retroceded: ‘My daughter learned to walk in the park. When she got older, I took her rollerblading there. It was full of plane trees and rose bushes. That area of the park was a wonder to me. I miss it.’

In 2012 the District City Hall decided to sue Maria Cocoru, aiming to bring the receded part of the park back under public ownership. A 10-year lawsuit unfolded, during which the space was in legal limbo. It was at this point that the general public found out about the status of the park. In the end District City Hall failed to present the necessary proof that the area in question was ever a park. It didn’t show sufficient evidence that the area was ever developed as a recreational space or that it contained other public utility facilities of local interest. It lost the case in favour of the owner before the High Court of Cassation and Justice in October 2022. According to witnesses of the trial such as Dan Trifu and local councillors, no testimonies were presented in court, no documents that show the investment of the City Hall in the park’s redevelopment. Dan Trifu said the lack of proof made the trial’s legitimacy questionable.

Recreation under fire

Occasionally, a civic group organizes picnics in the retroceded area on ash-covered, black earth. The gatherings are not intended as protests in the classical sense but rather as a symbolic reconnection with a place that should belong to everyone. It is a means for locals to meet and engage in social activities: eating, chatting, taking pictures – all amidst a desolate landscape. The picnics are a form of alternative protest, where activists want to not merely adjust to the existing desolate space but to reinvent and reimagine its potential. They transform the retroceded, private section of the park into, at least for a few hours, a space for leisure and communal joy.

They are connected to the group Here Was a Forest / Here Could Be a Forest established in 2023, where artists, joined by disgruntled and desperate residents of the area started to organize regular protests near the park. They demand that the 12 hectares of illegally private property be transferred rightfully back to public ownership, claiming that the authorities ‘have turned a blind eye’ to the injustices that have happened to the park. They feel that local citizens are not truly consulted regarding urban development planning.

Andreea David, who organizes the group’s protests, says that members have organically assumed their roles over time. Others are involved in documenting and researching legislative issues and archives related to the history of the park, or writing requests and sending petitions to public institutions such as the Local Police of the Municipality of Bucharest and the City Hall of the District, urging them to take immediate action. The group also produces an online and print newspaper, The Titans Don’t Sleep, which documents the case. They have a website acting as a digital information platform for anyone interested in the history of the park and its retrocession, as they think it’s important to trace the memory of the park and register the stages of its destruction.

Going one step further, IOR-Titan Civic Initiative Group, one of the longest-established campaign advocacy groups for the park, initiated a lawsuit in May 2024 suing Bucharest City Hall’s 2005 retrocession decision. This action, they hope, will be decisive for the fate of the park. If they can prove in court that IOR was illegally retroceded, the City Hall will be able to reclaim the land and make it public again. Painstakingly investigating the City Hall’s archives and cadastral documents from the 1980s and 1990s, the group argues that IOR was a park in its entirety since it was built and its status as a public space was never officially changed until the 2005 restitution, therefore making its restitution illegal.

IOR Park protest, Bucharest, Romania. Image courtesy of the author

As Trifu explains, proving the illegalities of the restitution of green spaces and parks in court is a more sustainable, long-term solution than expropriation since only very few expropriation cases have been successfully made. ‘Most of the time when we argued for expropriation, the municipality responded that it doesn’t have enough funds to do that. I told them to take another look at how the restitution decisions were issued: do these people actually have the right to own these areas?’

Planned destruction

Importantly, there is a law that, at least theoretically, should protect green spaces in Bucharest. Emergency Ordinance 114/2007 prohibits the change of use for green spaces, regardless of how they are listed in urban planning documents, regardless of whether they are public or private.

This law, along with the Green Spaces Law 24/2007, should block real estate developers obtaining building permits on green spaces, and yet, in many cases, the law is seemingly insufficient for preventing the destruction of parks. When nature stands in the way of profiteering, real estate developers erase any evidence that a particular land was ever a green space, so that the law cannot protect it anymore. As long as trees are growing in retroceded land, they cannot build anything there. The fires are an aggressive method of accelerating the process towards obtaining construction authorization.

Experts, locals, activists and the few politicians who have made public statements on the IOR’s destruction have described the arson as a strategy by owners to clear the space for a high-rise complex, hence the urgency to remove all the trees and, indeed, the entire ecosystem in that area. Those who administer the land have already set to work, renting it out to various interested parties, who have begun setting up an amusement park on the charred land. Inflatable slides and carrousel, train and car rides for children have appeared in the burned, apocalyptic landscape. Appearing out of nowhere, the ‘amusements’ are not covered by a permit, no name has been associated with the project, no start nor finish date has been mentioned.

To date, 90% of the IOR park’s retroceded area has been burnt. The view is striking: piles of blackened trees lie on top of one another; the land is so scorched that nothing is growing there anymore. Regeneration looks impossible. The idea seems to be that, eventually, local citizens will no longer have anything to fight for, that they will be silenced.

In a public statement to the press, Eugen Matei, local councillor for District 3, reinforces this hypothesis: ‘They cut down the trees to be able to claim that there is no actual green space. It’s akin to the tactics of those who had listed houses, which they neglected until they collapsed, and could then request demolition and construction permits for buildings with ten floors.’

Ana Ciceală, president of the Environment Commission of the General Council, is of the same opinion. The fine for illegal logging, when paid within two weeks, is only between 5-100 lei per tree (around 4 euros). Ciceală is the sole politician who has proposed a law to the General Council of Bucharest arguing for an increase in the fine: 1000 euros per tree.

But her draft stalled in the Council, due to a series of abstentions and rejections. Ciceală explains: ‘Councillors said they could not approve this project because Bucharest City Hall isn’t issuing deforestation permits quickly enough. Their argument is basically that they should not issue large fines, even though they are illegally allowing the cutting down of hundreds of trees, because of a permit bottleneck.

With permits being bypassed, there is no clear evidence of how many trees in Bucharest are being cut for valid reasons. No transparent records are kept on how many trees are cut down annually, on what grounds and how many have been planted to replenish stocks. Consequently, there are countless reports in the press about people being caught with chainsaws in hand, cutting down trees between blocks of flats, parks or green playgrounds – all areas that have been retroceded.

Impromptu amusement park, IOR Park, Bucharest, Romania. Image courtesy of the author

To make matters worse, tree conservation in Bucharest has also been affected by the modification of the Forestry Code. Up until 2020 all trees were classified as vegetation and managed under forestry regulations. Uprooting, felling or otherwise harming trees was considered a forestry offense and a criminal case could be filed. But this is no longer the case.

In addition, no register of green spaces functionally exists at a municipal level. Such a record would provide a fully accessible digital data base documenting each area of Bucharest’s current public green space. Although a register was drawn up in 2013 at the request of the European Union in order to establish and monitor the total green space index per capita in the capital city, it has not been updated, making it difficult to assess the actual reality of public urban green spaces. In addition, the register has not been approved by the General Council of the Municipality of Bucharest, giving it no legal value.

Protection conflict

Since 17 January 2022, when the first reported fire in IOR Park was registered, the response from authorities has been inconsistent. The local police commissioner has not made a public statement about the situation despite activists calling for answers.

Activist and resident of the Titan neighbourhood Beniamin Gheorghiță explains the arduous process of engaging authorities in protecting the area. It took much convincing before surveillance cameras were installed in the retroceded area and now only 3 out of 12 are operational. According to an ISU Bucharest-Ilfov (the General Regional Inspectorate for Emergency Situations) statement requested by Gheorghiță, 28 fires have occurred in the retroceded area of IOR Park from 17 January 2022 to 26 August 2024. In the institution’s statement, the cause of 21 of these fires was connected to discarded cigarettes. However, the likelihood of the same place accidentally burning so frequently due to negligence is highly unlikely. As for the remaining eight counts, no information has been communicated as to who started the fires or why. Some of the locals, including Benjamin, regularly attend council meetings where they put forward their concerns about the case, but no further action is being conducted.

In July 2024, when walking in the park, Gheorghiță caught two young men with axes in hand as they struck at the base of several large plane trees, most probably with the intention to weaken them, so they would fall quicker. All of this happened in front of the police. When Gheorghiță intervened, drawing their attention, he received a death threat from the tenant, who appeared on the scene and addressed him by name, even though they had never met before. This incident made him fear for his life; he now has a video camera in his car, at the entrance of the housing block where he lives and on him to document any potential attack.

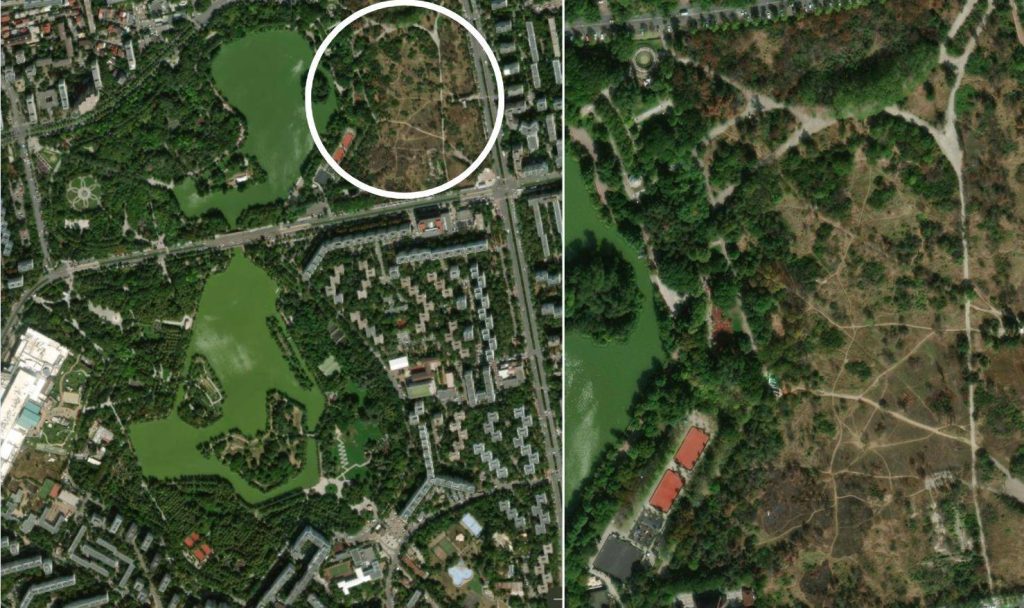

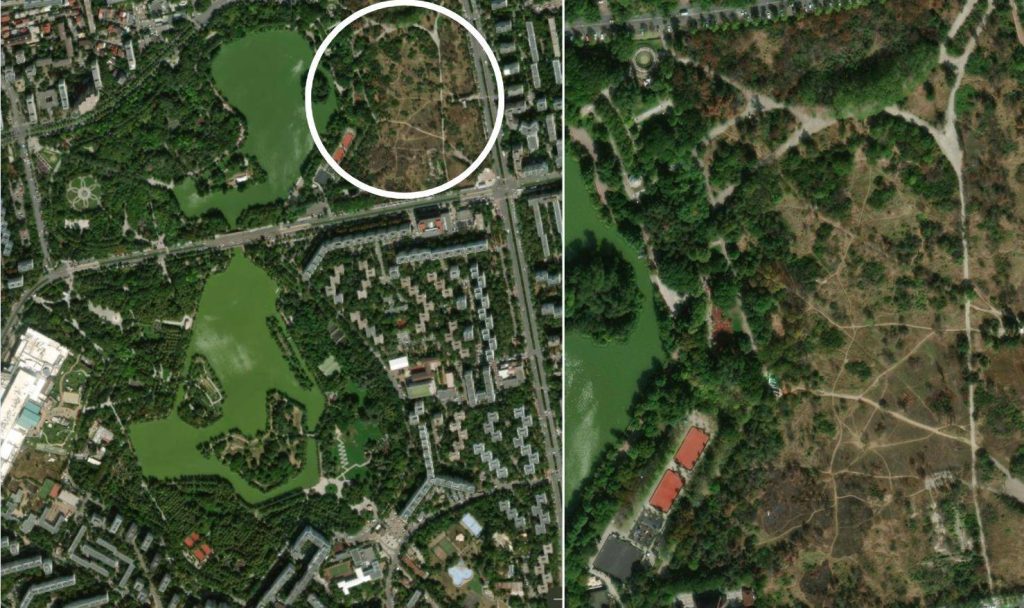

The map shows the IOR park and its fire-ravaged area. Images via Maps

The fires continue despite protests and complaints. After two years of reported incidents, only one person has so far been remanded in custody. A month after the suspect’s arrest in August this year, another major fire broke out on 9 September while the man was still in pre-trial arrest, raising suspicions among locals that more people are involved in the arson. This was one of the most powerful fires to date, destroying two hectares of vegetation. The smoke was so thick that it reached the subway entrance near the park, which thousands of people use daily. People in the area feel terrorized. Apart from the pollution, discomfort and harmful effect the smoke is having on their health, they fear that the next fire might cause casualties.

Health and wellbeing

According to a statement in the press made this summer by Bucharest’s Mayor General, Nicușor Dan, the city has lost 1600 hectares of green space since 1990. About 300 hectares of green spaces have been retroceded. Gardens, lakeshores, courtyards and squares, sections of parks and urban woodlands have been turned into apartment blocks, parking lots, shops and malls. The green areas that remain are at risk of disappearing because existing laws do not protect them sufficiently. At the local level, the Municipality of Bucharest does not have a specific policy or legislation to cover elements related to biodiversity, management of protected natural areas, and the conservation of natural habitats, flora and fauna.

Several institutions and NGOs have called for an urgent Green Spaces Register. The National Environmental Guard even issued the Bucharest City Hall with a fine of over 20,000 euros in 2021, but, to this day, there is still no such public tool for registering and managing the city’s public urban green space data.

EU environmental policies are putting more emphasis than ever on bringing nature back into cities by creating biodiverse and accessible green infrastructure. The EU’s 2030 biodiversity strategy, for example, emphasizes the importance of developing urban greening plans in larger cities and towns, encouraging local stakeholders in each member state to introduce nature-based solutions in urban planning to achieve climate resilience. Climate change, inadequately planned urbanization and environmental degradation have left many cities vulnerable to disasters, and such policies could be crucial for the liveability of urban areas.

According to the 2022 ‘state of the environment in Bucharest research report’, the city has approximately less than 10 square meters of green space per capita. Bucharest’s oxygenated environment is, therefore, supported by less than one tree per person, placing it among those European cities with the least urban green areas. Data on the surface of overall green infrastructure in Bucharest varies, but in 2018 a European Environment Agency study measured around 26% of urban-green-area coverage, significantly less than the average 42% in the 38 EEA member countries. In Romania, high-level pollution is linked to a growing number of diseases such as respiratory infections, heart attacks and strokes. According to a study by the European Commission in 2021, air pollution contributed to approximately 7% of deaths (over 17,000 deaths) in Romania, a higher share than the EU average of around 4%.

The case of Bucharest’s disappearing trees and urban nature, which finds its most aggressive manifestation in the IOR park, reflects how environmental and urbanistic problems do not exist in a vacuum. They are a direct reflection of how corruption impacts human lives and corrodes the relationship between people and the space they inhabit.

Without a management plan, developers build unchecked, contributing to a reduction in urban biodiversity. The current situation underlines the urgency for clear regulations and protection of Bucharest’s natural heritage. It also highlights the poor legislation and lack of environmental awareness on the part of public institutions, as well as an interest in immediate, short-term profit at the expense of the well-being of the people and the sustainability of the city, especially in times of climatic changes where resilience is needed.

What is occurring at IOR could be a never-ending story, constantly repeating itself in other locations if certain bureaucratic and profiteering realities do not change course, if the root of the problem stays the same. Despite all odds, people continue to fight to bring the space back into the public domain. Their hope remains.

This article was written within the Gerador mentorship programme in collaboration with Eurozine, part of the EU-funded Come Together project leveraging existing wisdom from community media organization in six different countries to foster innovative approaches.