Two thousand and thirteen was another busy year for migration correspondents. While anxiety about the movement of EU citizens captured headlines as it drew to a close, the deaths of migrants at Europe’s external border remained one of the most broadly covered issues. But did the public shock, media coverage and political pledges of solidarity following the deaths at sea amount to a genuine determination to bring about change – or will the body count continue in 2014?

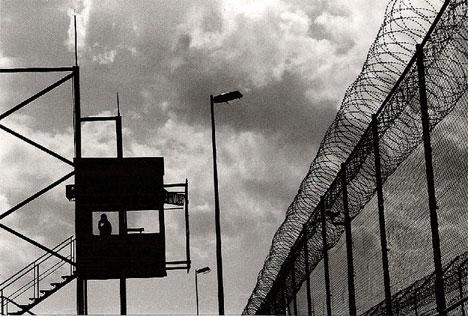

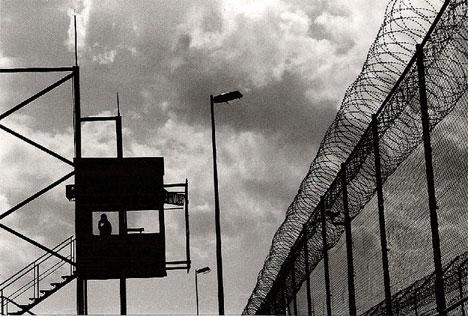

Fence around the Spanish enclave of Melilla. Photo: Sara Prestianni. Source: Flickr

In October, a boat carrying hundreds of migrants sank near the Italian island of Lampedusa, leaving more than 165 dead. This was not the first nor will it be the last migrant boat to sink in EU waters but the magnitude of what eventuated and its widespread coverage brought renewed criticism of the EU’s approach to border management and irregular migration.

“A senseless tragedy”, news correspondents assured viewers as reports of the deaths broke. Yet the term implies less causality and more misfortune then the well-documented record of corpses mounting at Europe’s border would indicate.

While for many news viewers and readers, the Lampedusa deaths provided a rare glimpse into the human suffering taking place at Europe’s borders, such cases are not new. Indeed, the European network United for Intercultural Action has documented the deaths of more than 17,000 migrants since 1993 as a result of Europe’s immigration policies.

In expressing their condolences to the Lampedusa bereaved, EU and national leaders were quick to offer the European Border Surveillance System (Eurosur) as a watertight solution. This new European border-surveillance system would, they said, ensure greater co-operation among member states to protect migrants. The European parliament, whose serious concerns over lack of accountability and transparency regarding the border-control agency Frontex had led it reserve 10 million euros of its 2013 budget until a fundamental rights officer was put in place, suddenly called for increased funding for the EU’s highest funded operational agency. The European Commission pledged that Eurosur would help member states identify and track vessels at sea, thereby improving search-and-rescue operations.

With expected operational costs of 144 billion euros over the next six years, will Eurosur really prevent loss of life? With the Mediterranean already amongst the most patrolled seas in the world and systematic reports of refused help and push-backs by police, border agents and coastguards, many are sceptical.

Assistance to undocumented migrants, including for humanitarian needs, is criminalized in many member states.

While the Italian president, Giorgio Napolitano, lamented the “slaughter of innocents”, those who survived the Lampedusa shipwreck faced criminal trial in Italy on grounds of irregular entry. This was in accordance with the 2002 “Bossi-Fini” law, advanced by the respective leaders of the nationalistic Northern League and “post-fascist” National Alliance in Silvio Berlusconi’s second government. Legislation criminalising irregular entry and stay is common across the EU, resulting in frequent prosecutions of undocumented migrants and their defenders, in France for example. But the case reopened the debate around the criminalization of migrants in Italy and a petition to repeal the law, led by La Repubblica newspaper, gathered more than 100,000 signatures in four days.

Unfortunately, at EU level the debate on migration follows a cycle:

1. migrants die;

2. leaders mourn the dead, while imprisoning and prosecuting the survivors;

3. politicians affect disbelief that restrictive and control-based policies lead to death and suffering;

4. there are calls for more restrictive and control-based policies;

5. return to point 1.

If only the deaths of 165 men, women and children which took place on 3 October could genuinely be called a “tragedy”. If only the reported rape and torture in Libya of some of those who died while attempting the journey were indeed “unfortunate” – rather than the expected outcome of the externalization of the EU’s borders through readmission agreements with third countries, which seek to shift responsibility towards migrants and prevent them at any cost from reaching EU territory.

If only the brutalization in an Italian refugee camp of several survivors of that same boat, recorded in grainy mobile-phone images, were “an accident” and not symptomatic of the often mandatory, occasionally indefinite and systematically inhumane policy of imprisoning men, women and children just for being migrants. Rather than being contingent, these instances exemplify the EU’s increasingly ill-informed, elitist approach to managing a phenomenon which the public fear, the media misunderstand and the politicians stigmatize.

Fair regular migration channels needed

Irregular migrants are often blamed for Europe’s economic ills. Yet while countries such as Greece, Italy and Spain have witnessed increased racists crimes and populist discourse scapegoating migrants and calling for increased restriction of their rights, most of the undocumented in Europe do not enter irregularly. Instead, they experience difficulties in renewing their residence permit or complying with increasingly tight requirements for renewal. In many cases, migrants become irregular through exploitation by their employer or losing their status due to spouse-dependent visas.

The EU-funded “Clandestino” research initiative demonstrated that irregularity is largely the result of exploitation, misinformation and administrative delays, while irregular border-crossing is the least common pathway into irregularity. Providing an aggregate estimate of 1.9 to 3.8 million irregular migrants in the EU, the findings are a clear challenge to the well-versed narrative presented in the media and by politicians.

What is needed are better and fairer channels for third-country nationals to take up work in key sectors of the EU economy. That requires a new approach.

After Stockholm

While for most of us, reflection and resolution is an annual process, the EU sets out its goals and objectives multi-annually. From Tampere to the Hague and, most recently, the Stockholm Programme, the EU’s justice-and-home-affairs frameworks outline priorities and actions for five years at a time.

These have steadily moved away from the goal of near-equality for all residents in the EU, with a strong foundation in human rights, to the idea that rights belong to citizens alone – and that a “security” approach to migration is needed to protect the fundamental rights of EU citizens. This is contradicted by evidence from the ground indicating that increased securitization and discrimination against migrants has neither reinforced the freedom, security and well-being of EU citizens nor curbed irregular migration.

As this is the year in which the Stockholm Programme (2010-2014) draws to a close, the European Commission is undertaking an assessment of its approach, before moving to a new framework on migration and asylum. If this is to bring any amelioration, there must be recognition that migration is not a criminal activity and that policies which treat it as such are ineffective, inappropriate and dangerous.

Political statements of shock must give way to the realization that exposing migrants to violence, exploitation and trafficking and deaths – and tearing families apart, through detention, deportation and restrictions on reunification – contradicts the founding principles and goals of the EU, as well as the obligations of member states to protect the rights of all people in their jurisdictions, regardless of administrative status. Media reports of “tragedies” must be replaced by informed, analytical and non-biased coverage of migration.