Bankrupt

Wespennest 189 (2025)

Bankruptcy in nineteenth-century parables of capitalism; billionaires, bankruptcy and the American obsession with money; and why the refusal to accept the end makes life worse.

After moving from Johannesburg (Jo’burg) to Gothenburg (Go’burg), filmmaker Jyoti Mistry struck up a friendship with someone who went the other way: Katarina Hedrén, who was adopted by a white Swedish family, and moved to South Africa as an adult. This deeply personal take on race shows how ‘colour-blindness’ denies that racial prejudice exists but robs people of colour of words to talk about the discrimination they face.

There are three ways to start this film project, but each would have to position protagonist Katarina Hedrén, the inspiration for my film, at the centre. It is through her experiences and observations that I begin to understand the place I arrived: Sweden.

I moved a long way from South Africa, from Johannesburg (‘Jo’burg’) to Gothenburg (‘Go’burg’). Katarina Hedrén, however, is Swedish and moved to South Africa several years ago. We met in Jo’burg and became friends. Now, after trading places and living in opposite hemispheres, we have found ways to reflect on histories (both personal and political), memories, and language. This is an enquiry into what it means to move to a different place in the world, finding ways of belonging or exploring what ‘belonging’ might really mean. We delight in the observations of our cultural contexts and whisper in hushed tones, questioning for ourselves if Swedes are really human.1

Opening 1:

EXT – SNOWY FOREST PATH, FALUN FOREST – DAY

Trees stir slowly with heavy-laden snow. There is silence, stillness present that only comes with snowfall. A figure, KATARINA clad in snowsuit with ski mask and goggles moves steadily on the cross-country path, moving skilfully.

VO – KATARINA

I have a special memory from Foskros, when I was skiing alone in the woods – there were 2 cross-country tracks, one was 2.5 km (the red track) and the other 5 km (the yellow track). At a certain age I advanced to the yellow track. Being all alone on that track, surrounded by trees only and hearing only the sounds of the forest, is almost indescribable; so peaceful and soothing. I feel it and smell it as I write this, so the notion that I wouldn’t belong is absurd.

Opening 2:

EXT – CITY OF FALUN – DAY

Images of the city of Falun with church at the centre. The abandoned industrial copper pit contrasted by the Faluån river, flowing through the city. Small quaint houses on each side of the river bank. The trees lush in Spring time bloom.

VO – KATARINA

I grew up in a small city called Falun in Sweden and moved to Johannesburg, in South Africa in 2005. It’s a strange coincidence that I moved from one mining city to another and I have only just started thinking about what this might mean. The copper mines of Falun were shut down in 1992. Johannesburg’s gold mining history starts in 1886. It’s a huge pulsing city with no river, arid and dry, its only bridge, the Nelson Mandela Bridge hangs over a set of train tracks. Johannesburg is a magnet-city attracting people from across the continent who come in search of jobs and to find their dreams. Maybe, I too came to Johannesburg in search of something.

Opening 3:

EXT – SNOWY CITY OF FALUN AT CHRISTMAS – NIGHT

Families with children at the Christmas market. The streets are decorated with festive coloured lights that reflect on the snow. The river banks on each side in a misty, mysterious glow with the haze of snowfall. Distant sound of Christmas jingle. The recitation from the poem Tomten.

VO – KATARINA

Så har han sett dem far och son,

ren genom många leder,

slumra som barn,

men varifrån, kommo de väl hit neder.Släkte följa på släkte snart

blomstrade, åldrades, gick;

men vart?

Gåtan som icke låter gissa sig,

kom så åter.(Subtitles)

Thus he has seen them, sire and son,

Endless numbers of races;

Whence are they coming, one by one,

All the slumbering faces?

Mortals succeeding mortals, there,

Flourished, and aged, and went — but where?

Oh, this riddle, revolving,

He will never cease solving!

My thoughts on the opening of the film are strained. In each of the scenarios, I am committed to introducing Katarina in her Swedish environment but never directly revealing her – we do not see her face immediately on screen. Instead, I want an audience to hear the lilt of her voice as she recalls the smells and textures of the forest, to see the ease with which she glides on the snow, belying her speculation that she might not belong.

The contrasts between Falun and Johannesburg in the second scenario are clear but, again, I want to insist on her Swedish identity through place. In the third possible opening, the recitation of Viktor Rydberg’s well-loved poem Tomten, an iconic Christmas narrative of a mystic creature (a gnome), who contemplates the meaning of life as he reflects on all living creatures, the cycle of seasons, life, ageing, and death. It is a way of reminding us that all creatures – ‘endless numbers of races’ are part of this cycle.

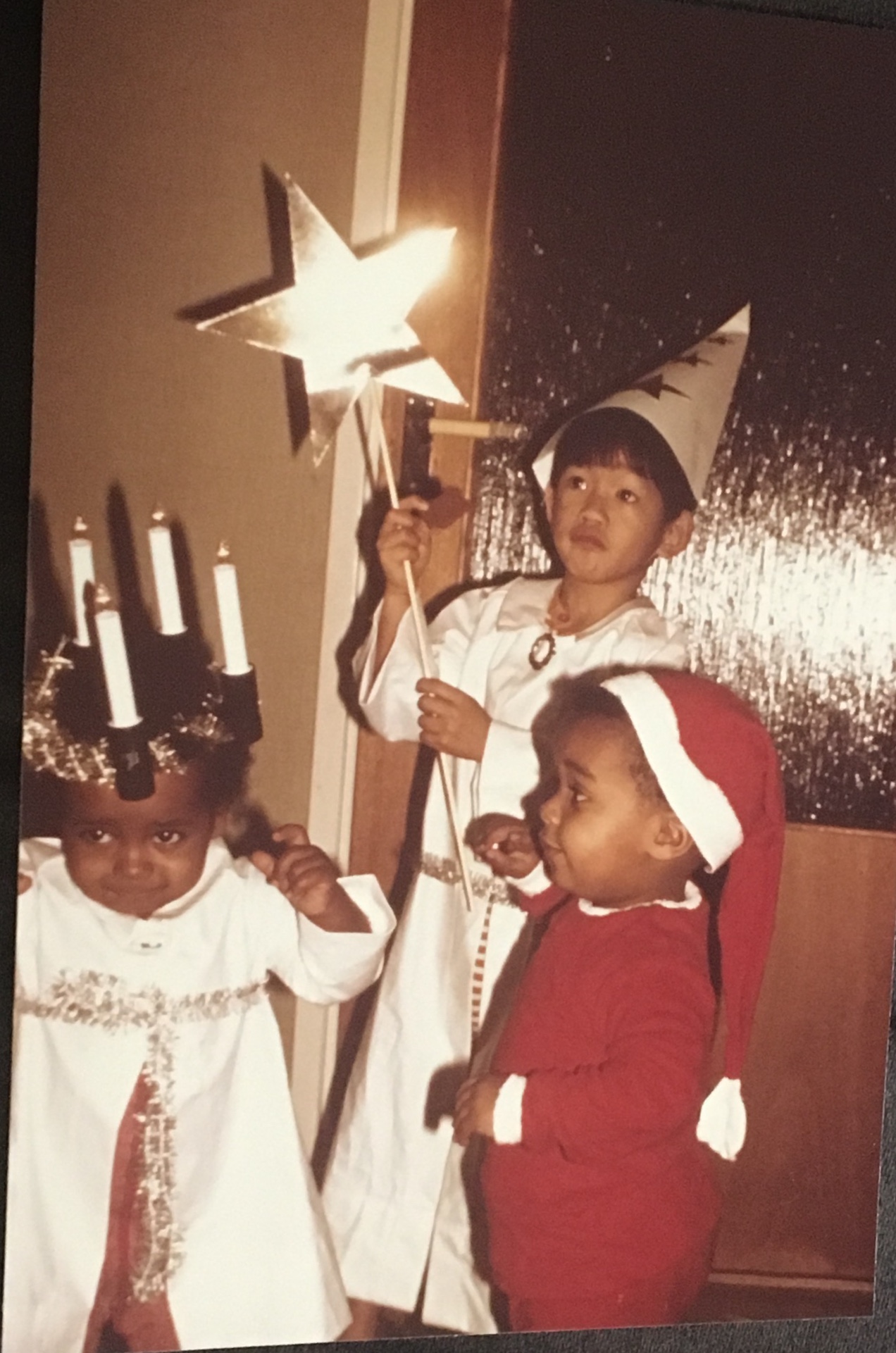

So, in a country that is not comfortable talking about race, how does one begin the story I am interested in telling: that of Katarina Hedrén who, in 1972, at the age of two, was adopted from Ethiopia by a white Swedish couple. Her father was a mathematics professor and her mother a school teacher. Their decision to adopt is central to the film: what are the personal reasons that motivate people to adopt children from far-away countries? Katarina and her twin brother are two of five adopted children, with an older brother from the Philippines and two younger sisters from Guatemala.

Katarina with her sisters. Private family photo, courtesy of Katarina Hedrén.

The Swedish ideological position on transnational adoption is one of the longest standing in Europe; an ingrained sense of ‘doing good’ is central to the doctrines of Swedish exceptionalism with its insistence on a humanism predicated on racial ‘colour-blindness’. In affirming this position, race is not part of the Swedish lexicon. This has created an especially complex problem of denying that racial prejudice even exists in Swedish society. Moreover, by not acknowledging and, in fact, even denying race, the lived experiences of many transnational adoptees neglect the racial dimensions that challenge the lives of minority-adoptees living in Sweden.

Many adoptees have written or documented their experiences, revealing conflicted and contradictory positions. On the one hand, they are accepted through language and culture. On the other hand, they have experienced discrimination based on race and ethnicity.

1 April

Dear Katarina,

I have been looking regularly at the photographs you sent me of your childhood, always trying to make sense of it in two ways. On the surface there is an exceptionalism to the photographs: so many brown children, amongst their parents and the family at festive events: the mix of races at the family Christmas dinner table, the white grandmother with the little brown child on her knee and the white mother with her brown children doing activities or playing, as any mother would. But then, there is an ordinariness to them: such a normalcy, an everyday banality that is simply about the way in which parents care for children and how families record the growing of their children, family occasions and then photos that show the special moments, like walking at the top of a hill with the mountains in the background with you and your brother swinging arm in arm with your mother on what looks like a family holiday (hike).

Katarina at Lucia. Private family photos, courtesy of Katarina Hedrén.

2 April

Dearest Jyoti,

I’m thrilled. Your eyes and reflections on my family are likely to make me see ‘us and them’ with new eyes. Exceptionalism and race – being raced – in a life and a place otherwise ordinary where, from the moment my childhood cuteness wore-off in fifth or sixth grade, I wished for nothing else than to blend-in. The story of my life.

Katarina with her grandmother. Private family photo, courtesy of Katarina Hedrén.

In my reading of the research of sociologists Tobias Hübinette and Carina Tigervall, this ‘blending in’ is described as an internalized experience in which one appropriates the characteristics and values of the environment. They observe that‘adoptees have more or less fully internalized colonial and racial stereotypes, even if they biologically are non-whites themselves. Given that they have grown up and usually live in wholly white neighbourhoods and surroundings, this internalization of racist images and fantasies is neither a surprise nor something deviant. To avoid being taken for a non-Western migrant, [adoptees go] to great pains to avoid other non-white people and‘’ adoptees.’Tobias Hübinette & Carina Tigervall, To (not) name the unnameable and (not) speak about the unspeakable: Writing about experiences of racialisation among adult adoptees and adoptive parents of Sweden on academia.edu

Growing up in apartheid South Africa, this schism was apparent in how I internalized race; how it produced stereotypes and connected to aspirations and what exceptionalism meant inside the Indian community, and outside it in the broadest sense. Under apartheid, racial segregation meant that one lived with an imposed homogeneity of black, white, Indian, and coloured communities. They not only created stereotypes of each other, but reproduced cultural and racial essentialisms themselves. To mark oneself outside of the stereotype, I would hold myself apart from particular registers of ‘Indianness’. In my memory, these registers had to do with values and aesthetic choices, like how I wore my hair, my sense of dress, or the language or arts and culture events I found myself gravitating towards.

More than anything else, I loathed the images of obedient Indian women I was confronted with in Indian cinema. In the Indian community in South Africa, there were strong female role models who were political activists and professionals. There were, granted, not too many of them, but they were visible and prominent. But I would still feel an unease to be seen to be ‘like one of them’ and I frequently avoided contexts of public Indian gatherings. Reading Hübinette and Tigervall’s research, I begin to wonder about how racial self-loathing is not simply about the desire to blend-in outside racially homogeneous spaces, but the wish to be read outside of stereotypes and, more significantly, how the accumulated pressures of avoiding stereotypes is about proving one’s (black) exceptionalism.

It takes time to develop a connection to one’s race that is determined from within and not imposed from the outside, from the Other.

2 May

Dear Katarina,

In the film I have in mind a sequence where I am in conversation with your mother. We do not talk about you, your siblings – the children she raised in her home. I am curious about her life with your father; her husband, the man she lay in bed with. What was the whispered coaxing that invites hopes, dreams and desires to move from one adoption then, the next (twins) and then a third adoption (that arrives as a pair of young girls) – the decision to no longer adopt babies or toddlers but sisters to complement your age at eight. What are the desires that fill the void of a childless existence?

I think of the questions I would pose to your mother: How does a woman make this decision to raise five children that are from such different geographic and historical contexts? What role does a man, her husband, your father have in providing for five children when a woman is left to care for them?

‘… there is an ordinariness to them … how families record the growing of their children, family occasions and then photos that show the special moments, like walking at the top of a hill with the mountains in the background with you and your brother swinging arm in arm with your mother on what looks like a family holiday (hike).’ Private family photo, courtesy of Katarina Hedrén.

13 May

Dearest Jyoti,

Surely there was love, ambitions to mother (and not just to care-take like a janitor or teacher), surely there was love at the heart of it and at the beginning hopes, dreams and desires.

In my adoption papers that I look at every now and then, I read that my parents committed in writing to care for us (my brother and I) as if we were their own children…

What does that even mean? It’s not a sarcastic or rhetorical question, I actually want to know what they meant, what we mean, what would I mean…

What were we if we weren’t to become that? (Their Children).

It implies we would never (be their children), but that they committed to act as if and for a lifetime, imagine that.

It boggles my mind and my soul. I’m still in search of ways of talking about the adoptive-experience that is more existential than exceptional, that includes more verbs, poetry and abstractions rather than nouns and statistics, and which touch on what it means to be a human being and to exist in this world where origin and belonging are such crucial components. An adoptive child is so often spoken about as a phenomena… as opposed to a child. Even adopted adults are spoken of as adopted children (adoptivbarn).

‘If you don’t know where you’ve come from, how do you know where you’re going?’

Can’t stand that one… it sounds like an accusation.

The bureaucratic structures that scrutinize and assess adopters’ abilities to provide and care for adoptees is commonly measured in the material security of guardians: their income and resources, as opposed to the emotional mettle required to cope with complex histories of trauma or isolation – often part of the psychological constitution of children arriving from orphanages through adoption agencies.

Transnational adoption always bears the stigma of being ‘rescued’ – that life in the first world can only be better for a child from the third world measured, again, against the odds of economic, socio-political, and infrastructural risk that children are exposed to in their ‘home’ environments. The good intentions behind ‘rescuing’ a child in need seem to fulfil the hopes, dreams, and desires of childless couples. But little work has been done to question what preparation guardians are given to address the complexity of racial prejudices and discrimination adoptees face in a country that has systemically denied the existence of race.

Re-enactment 1:

INT – HAIR SALON, JOHANNESBURG – DAY

KATARINA sits in a salon chair dressed in skinny black jeans with a black turtleneck and thin-heel ankle boots. Close up shots of her hair being braided into long dark-auburn dreadlocks.

Intercut with photographs from KATARINA’S childhood in her short-close-cropped hair. There are photographs with her mother, whose hair is also consistently short: wavy and strawberry-blond.

VO – KATARINA

I never thought of my mother as stylish, but groomed, the Swedish word, parant. My dictionary translates it as ‘very elegant’, ‘smart’ and ‘stylish’ but I would add ‘strict’ and perhaps ‘imposing’. I used to be envious of my some of my friends’ mothers – those with younger mothers who dressed in jeans and had long hair. I have this image-memory of my mother that nothing about her ‘flows in the wind’. She used a lot of hairspray. I used to give her cans of hair spray for Christmas. My own style no doubt is heavily influenced by this. I always say that my hair – the choice of locks down to my waist is a gift to my inner child who couldn’t grow her hair long. With hindsight I wished to be a mother with hair that flows in the wind.

The testimonies, stories, and memoirs of parents who have raised transnational adoptees and adopted adults trace fractured relationships. Their painful, and often confused, sentiments and unresolved feelings cannot, nor should be read as a binary opposition between ‘for’or ‘against’ such adoption practices,but rather invite a closer examination of what makes each story unique. It invites us to explore why some adoptees find paths they may call their own while others appear not to, or, dare I say, seem to lose their way in unresolved angers, feelings of abandonment, and feeling like they are never fully accepted or do belong.

Re-enactment 2:

EXT – MUNRO DRIVE, JOHANNESBURG – DAY

Munro drive is the scenic, meandering road that offers breath-taking views of the northern part of Johannesburg. KATARINA jogs alongside the waist-high stone walls that form the boundary for the edge of the road. The soundtrack is Kulning (traditional Swedish herding music) which renders a sharp disjuncture to the urban density.

VO – KATARINA

Where do you or I locate ourselves in a world where origin defines us? Where the question: ‘Where do you come from?’ means ‘What are you?’

How do I make sense of myself as an Ethiopian Swede in South Africa or you as an Indian South African in Sweden?

9 June

Dear Katarina,

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie has made a remarkable career from claiming that she was exposed to a ‘single story’ and warns against its dangers.2When I think of you growing up in Falun, I cannot imagine for a moment that there was any single narrative, one story that you were exposed to. And even if you had the single narrative of Swedish nationalism or Swedish myths and legends that intrigued you, there would have been conflicting and contradictory narratives from your experiences that challenged any certainty of the single story.

11 June

Dearest Jyoti

I’m intrigued by your choice of words, ‘Chimamanda… has made a remarkable career from claiming that she was exposed to “a single story”’… I agree with that. Not to say that she hasn’t contributed meaningfully, but she would be one of the first to create a single story about single stories, and an economy around that story. People like us must be careful not to become bit players in that circus that require black people whose only story is that ‘we need to tell our stories’… There are many stories, just like you say, and feelings of marginalization exist alongside feelings of being at home and belonging.

Among the photographs, documents, and letters Katarina has sent me is an image used in the mid-70s by KFUK-KFUM, the global organisation focusing on human rights and justice. The caption reads ‘A World in Cooperation’.

‘A World in Cooperation’. KFUK-KFUM leaflet, courtesy of Katarina Hedrén.

On the surface, the image evokes an aspiration of human solidarity. It is evident that the photograph is directed: the adult voice asking the children to look up and face the camera overhead and perhaps point-out the place that they are from, their origin. The photograph was taken in Sweden with Katarina and her siblings used in the poster campaign (the little white boy is a neighbour brought in for the picture). The picture suggests that ‘origin’ is the place where one ‘belongs’.

But where Katarina Hedrén – or any of us – finds a sense of belonging is often not where she or any of us are ‘from’. ‘Origin’ is a dangerous concept to affirm belonging. It is how racial prejudices are produced and is the language used to justify discrimination.

In an interview, James Baldwin talks about ‘home’ and its relation to belonging. He describes home as ‘something you take with you’. It is an evocative idea, different from the idea that home is a place that one leaves behind. One takes home ‘with you’, Baldwin suggests, as a way to understand more about where you have been and to know yourself more closely.

Henrik Berggren and Lars Trägårdh, Är svensken människa? Gemenskap och oberoende i det moderna Sverige, 2006

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=D9Ihs241zeg

Published 20 November 2019

Original in English

First published by Wespennest 177 (2019)

Contributed by Wespennest © Jyoti Mistry / Katarina Hedrén / Wespennest

PDF/PRINTSubscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Bankruptcy in nineteenth-century parables of capitalism; billionaires, bankruptcy and the American obsession with money; and why the refusal to accept the end makes life worse.

Parables of violence; memories of dictatorship; perversions of memory: Ord&Bild samples contemporary Latin American literature and photography.