Three years ago, on 21 November 2013, the protests commenced on the Maidan Nezalezhnosti, or Independence Square, in Kyiv, that quickly became known as Euromaidan. Euromaidan, because the Ukrainian government had broken off negotiations concerning the Association Agreement with the European Union shortly before they were due to conclude. This drove thousands of enraged people onto the streets. What followed is history: first the removal of Viktor Yanukovych’s government and then the involvement of Russian troops in occupying Crimea, as well as areas of eastern Ukraine. Since then, Ukraine has remained a partially occupied country like Moldova. The independent state of Ukraine had only existed for a quarter of a century, a mere heartbeat in terms of world history. Nonetheless, until now, a Ukrainian state had yet to exist for “so long”: for the first time ever, a generation has grown up in it. But why couldn’t Vladimir Putin finally accept this?

Ukraine mosaic, Kharkiv. Photo: Fandrey. Source: Flickr

The Ukrainian author Andrey Kurkov, perhaps the most popular Russian-language writer in Ukraine, sees in Putin only a prime example of many Russian politicians who, up until today, do not wish to understand that Ukraine is not Russia. “Three Soviet leaders came from Ukraine, that is, three out of seven in total. And no Russian politician ever understood the different mentalities. In Russia there was only one political tradition: the monarchy. This applies to the Soviet period too. Thus, every General Secretary – except for Khrushchev – remained in power until his death. Everyone should love the new tsar, just as they should Putin now too. In Ukraine there is no such monarchist tradition; since the sixteenth century, thanks to the Cossacks, we have an anarchistic tradition too”.

In fact, breaking away from the Soviet Union was no amicable separation. After the failed putsch in Moscow, the parliament in Kyiv declared Ukraine’s independence on 24 August 1991. Mikhail Gorbachev, who wanted to save the Soviet Union at the time, responded harshly: “There can be no Union without Ukraine, I feel, and no Ukraine without the Union. These Slavic states, Russia and Ukraine, were the axis along which, for centuries, events turned and a huge multinational state developed. That is the way it will remain.”

This long, shared history underlines too the ties between both peoples, which extend much further than those with the Baltic states, for example. Most Russians have never accepted the loss of Ukraine and, above all, of Crimea. This explains why Gorbachev, romanticized here in Germany as a shining light, and Vladimir Putin, who is vilified as a scapegoat, are of the same opinion when it comes to Ukraine.

And in fact, many people did not feel at home after 1991 in the new country of Ukraine, especially in those areas later annexed by Russia or overrun by war. In occupied Donbas, there were already attempts even in 1993 to establish autonomy within Ukraine;

Crimea received this autonomy but, in the view of the decidedly western oriented Ukrainian-language writer Yuri Andrukhovych, remained the Achilles’ heel, the irresolvable aporia of his country. For Andrey Kurkov too, Donetsk and Luhansk comprised the core of the eastern region even before the war – that is, the region from which the separatists had to withdraw, despite Russian military support and initially large territorial gains. However, close to the Russian border, the attractive city of Kharkiv held its position as the Russian Spring faded.

In Ukraine, Putin ultimately achieved the opposite of what he intended (unlike in Russia): the war in the East united the rest of the country, which remains the largest fully-fledged state in Europe. However, Russian aggression seriously aggravated Ukrainian nationalism. The population of the crisis-hit region in the East are faced with a daily battle to lead a halfway normal life. Almost every day, there is an exchange of fire, often resulting in fatalities. It is an asymmetric war in reverse: a military great power operates like a guerrilla. Will Russia take more and more military gambles in Ukraine? Or has NATO provoked a war with its “sabre rattling and war cries” (Frank-Walter Steinmeier), gestures that the United States has helped to intensify?

Should sanctions against Russia finally be lifted – or tightened? And, given the increasingly authoritarian environment in which it finds itself, can Ukraine ever become a mature democracy? These are the major questions that present themselves today.

Cold War 2.0

Almost 20 years ago, in 1997, Zbigniew Brzezinski published The

Grand Chessboard, his standard programmatic work. Here, this “outstanding thinker”, as Barack Obama described the political scientist and presidential adviser, suggests how the United States might sustain its global primacy as the only world power for as a long as possible. Born 1928 in Warsaw, Brzezinski believes that the United State’s global hegemony depends upon “how long and how effectively its preponderance on the Eurasian continent is sustained”. The various states in this enormous territory

– from Portugal to Russia, from the United Kingdom to China –, unable to form a political unit, are merely pieces upon the great chessboard on which the struggle for geopolitical hegemony unfolds. Ukraine constitutes the linchpin, for without this classic borderland, “Russia ceases to be a Eurasian empire. Russia without Ukraine can still strive for imperial status, but it would then become a predominantly Asian imperial state”. This must become the United States’ objective. A genuinely united Europe – “a harmonious economic community stretching from Lisbon to Vladivostok”, as Putin put it in 2010 – would however weaken the hegemony of both the United States and NATO. At which point, who does not hear talk of old and new Europe from the Bush era ringing in their ears? Is the United States to blame, with its expansionist ambitions (using NATO as its vehicle), for the occupied areas and unclear borders in Ukraine and other countries in eastern Europe?

As often as this position recurs in geostrategic arguments: it ignores the attempts of many young people in particular to break free, first from the Soviet and then from the Russian empire. Pro-western movements and revolts repeatedly emerge, from the so-called Orange Revolution in 2004, to Euromaidan itself. Without these, European and American institutes could not have successfully functioned. Rebellions can of course be externally supported but they have to mature from within. And up until today, just as in the Cold War, it is only proxy wars that are possible between great powers – as the conflict in Ukraine shows. For military deadlock still persists between the United States and Russia. Both powers still have the option to destroy the world and themselves several times over, through the use of their nuclear weapons.

Russia’s partial resurgence

The history of nuclear weapons comprises a further reason for the current divisions in

Ukraine. Once founded, the country had at its disposal an enormous arsenal of nuclear warheads; no country could have attacked Ukraine without risking its own downfall. As tensions eased however, the country’s nuclear capacities were relinquished in accordance with the terms of an international treaty that guaranteed its borders. Russia too was a signatory. In breaking the terms of the treaty, the Kremlin chief incidentally brought about a situation in which no country would likely be willing to relinquish its nuclear weapons in the future.

At the moment, moderate tones are to be heard coming from Washington in discussions of the conflict in Ukraine: support for the Ukraine, yes, but not – as requested in Congress – in the form of weapons; sanctions against Russia but in moderation; protection for eastern European NATO countries and the posting of military personnel to the Russian border. Some months ago, Henry Kissinger spoke of viewing Ukraine more as a bridge to Russia than as an outpost of the West. One reason for doing so: there is no recognizable post-Putin Russia on the horizon. Putin is easing the pain after a dramatic downfall – albeit with placebos for the most part. After the Soviet Union’s implosion, Russia, a former empire, experienced severe turbulence. Still the largest country in the world, it lost control to the East and South over the Caucasus and Central Asia. Moreover, Russia lost almost all of the westerly territories it had gained, conquered and settled since 1600. It really was a once-in-a-century collapse that prompted Putin to speak of the demise of the Soviet Union as “the greatest geopolitical catastrophe of the twentieth century”.

What should the country do? It seemed possible to relinquish imperial status and become one of the liberal-capitalist states of the West. This path was never taken though, at least not with any consistency. There were attempts under Boris Yeltsin and at the beginning of the Putin era too; however, integration with the West failed – and it was not only Russia that was at fault here, but also the western defensive front against this “regional power” (Obama).

Given the failure of previous attempts, Russia’s integration with the West was probably not at all viable. Neither is the loss of an empire an easy thing to cope with; one only has to think of how long the United Kingdom required to accomplish this, at least to a certain extent. The latest superciliousness in the wake of the Brexit decision indicates that there is still some way to go. Just as other former colonial countries continue to exercise influence over lost colonies, Russia tries to do so in Ukraine (though the relation between the countries is yet more complex than that between colonial countries and their colonies). Is there then no alternative to the new Cold War? Of course there is, absolutely, though one thing’s for sure: the new Cold War is on any account a dead end in the labyrinth of world history. It cannot effect change in any progressive sense with regard to the increasingly blatant contradictions in Russia, Ukraine or elsewhere. After all, it is no longer a matter of (capitalist and communist) systems competing in such a way as to always yield positive social change. There is only disastrous competition between imperial powers with different capitalistic credentials.

British historian Perry Anderson makes a striking criticism of the inconsistency of Russian politics: “Putin’s belief that he could build a Russian capitalism structurally interconnected with that of the West, but operationally independent of it – a predator among predators, yet a predator capable of defying them – was always an ingenuous delusion.” Russia’s return to the political world stage, whether in Ukraine or Syria, therefore constitutes only a partial resurgence.

A mirror image of which is to be found in the self-deception of the West, stemming from its belief that countries like Ukraine or Russia can be integrated into its own political and economic system with no problems whatsoever. Today, one can observe in eastern Europe in particular that capitalism controlled by financial markets gives rise to contradictions that make such integration impossible. Moreover, the fight for Ukraine also reveals the deep layers of the history of Europe, including that of Russia.

The Ukraine crisis as Europe’s crisis

The new rise of the Russian Empire advanced with one eye permanently on the West. Peter the Great famously founded his new capital city on the Gulf of Finland: St. Petersburg. At the end of the century, Russia expanded and called Crimea its own; the Caucasus too belonged to the Empire. After victory over Napoleon, Russia was the strongest conservative, not to say reactionary, power on European soil. Parallel to the rise of Russia, three partitions – 1772, 1791 and 1795 – took place, which meant that Poland disappeared from the map for over a century. The expanse between Berlin, Vienna and St. Petersburg was divided up between Russia, Prussia and the Austro-Hungarian Empire. States first re-emerged in the region after World War I: Poland, the three Baltic states and, for a while, Ukraine too. World War II created the next caesura: thereafter, it was not only German history in eastern Europe, but also seven hundred years of Polish history in Ukraine that came to an end. The Poles were driven further westwards.

An epoch later, after the West’s victory in the Cold War, these states rose again upon the continent’s once frozen geopolitical landscape and, by their mere presence, nudged Russia further eastwards. In each and every case, Russia reacted by attempting to retain the various parts of its empire: it has a presence in the Caucasus, where it is supported by Armenia, and in the southwest of the former Russian and Soviet empires, in the half-state of Transnistria, which was detached from Moldova. Crimea became the first territory of a neighbouring state to be integrated into Russia.

Without taking the longer historical view, without considering the historical factors so deeply inscribed in the current affairs of Central and Eastern Europe, one cannot understand today’s events: the European West and what in Russia is known as russkiy mir, or “the Russian world”, merge into and influence one another right up to the present; they have entered into conflict previously, and continue to do so to this day. Ukraine, which in translation means borderland, still lies in the midst of these conflicts, and always has done. It is not without reason that Timothy Snyder called this region “bloodlands”. And in Mikhail Bulgakov’s Kyiv novel The White Guard, it is written:

[W]ould anyone pay for the blood?

No. No one would.

The snow would melt, the green Ukrainian grass would come up and plait the earth, lush sprouts would emerge, the heat would shimmer above the fields, and no trace would remain of the blood.

As regards Russia, the Regensburg-based Polish political scientist Jerzy Macków is of the opinion that it only ever took a few years, after the 1905 Revolution or the collapse of the Soviet Union for example, for a justified hope to surface that the “principle of legal nihilism rooted in medieval Moscow could have been replaced by constitutionalism, that is, by a form of rule that is restricted by law”. Looking to Ukraine, Macków has presented a five-point programme: international aid, tight controls, the combatting of totalitarian traditions, remembering the destiny of the Crimean Tartars and

a post-Putin-era peace plan for the undeclared Russian-Ukrainian war. This kind of programme currently comes across as being a long way off in the future. But, given the country’s short history, what will become of independent Ukraine if it remains a target of the larger powers?

The dream is over

Five years ago, I compared Ukraine to a twenty-year-old who, after a difficult childhood still had to find his place in life. It is still not obvious where this place might lie, although a preliminary decision has already been made about its western orientation. It is improbable that the greater part of Ukraine will connect to today’s Russian world. The desired place of the majority is still called Europe, oh Europe! Yet Ukraine’s difficulties on the way to Europe still cannot be ignored, as one can see for oneself in the country’s interior and on its borders: elderly women top up their meagre pension by selling fruit and vegetables, or their belongings. Bitter poverty in many villages and settlements. And in the larger cities, photos of soldiers killed in action and of seized Russian war equipment point to the huge deployment of Russian forces, the latter being something that the Kremlin continues to deny.

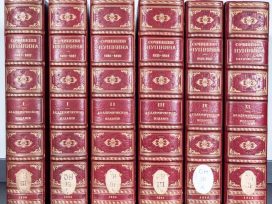

Thus Ukraine is today a deeply divided country, whether geographically, in terms of East and West, or socially, in terms of those people at the top and those at the bottom. More’s the pity that so little, on the other hand, is known about the country’s beauty: especially with regard to the 1500-year-old Kyiv and the qualities of its culture and surrounding landscape. Stand on the heights above the Dnieper, and you see not only the Kyiv Monastery of the Caves with its golden domes (a UNSECO World Heritage site), but how the metropolis is half-submerged in the green sea of chestnut trees and other vegetation, and half surges up again upon the wave of treetops. Also impressive is the westerly city of Lviv, where cultures and peoples cross paths along the Main European Watershed, and the southerly city of Odessa, the white city on the Black Sea. And finally, the city of Kharkiv to the East, near the Russian border. Here, “the boomtown of the Russian fin de siècle meets Soviet modernity on Ukrainian soil, the monumentalism of late Stalinism”. Ukraine is – and will probably remain so for the time being – a riven country.

A low intensity war of position troubles the occupied East; but the whole country – with the exception of its agricultural sector – is growing weaker economically, the situation of many internal refugees is pitiful. According to Transparency International, Ukraine lags behind Russia (in 136th place) as the most corrupt country in Europe (142nd).

Approval ratings for president Petro Poroschenko continue to fall, intensifying

the pressure on him to act.

One would certainly have to be an optimist to believe that an oligarch can initiate fundamental reforms, not that his doing so can be ruled out altogether. After all, revolutions from above have repeatedly taken place throughout history, even if the signs in Ukraine do not currently point to one happening there.

No democracy without minimum economic security

However, until the tide of history turns once more, it remains the case that all rebellions of recent years, from the Arab Spring to Euromaidan, were at best only able to achieve the removal of authoritarian rulers from power; until now, none of them has secured a bright democratic future. Political awakenings ended in economic ruptures. And these kinds of crises often tend not towards democracy but dictatorship. Out of the helplessness of the masses, grows the desire for the strong man. The radical change, which the democratic revolutions wanted to embody, ate their children, and continues to do so.

This just goes to show: democracy without minimum economic security is a chimera. How one establishes and maintains democracy in today’s global capitalism is an open question. During the Cold War, democratic movements proceeded in the name of freedom, against a culture of oppression, despite the existence of social security. In contrast to which, Euromaidan dreamed of a continent of freedom and human dignity. However, in spite of far stronger economic foundations, this dignity is threatened today in western Europe itself. New awakenings must therefore ensue, and always in the name of social equality or justice. Otherwise, it is to be feared that subsequent catastrophes will take on yet greater dimensions.