Cancel culture vs. execute culture

Why Russian manuscripts don’t burn, but Ukrainian manuscripts burn all too well

Just after the Russian invasion, the novelist Victoria Amelina wrote an essay warning that Ukraine’s cultural community faced the same fate as the Executed Renaissance in the 1930s. On 1 July, Amelina herself died of injuries sustained in Russia’s missile attack on a restaurant in Kramatorsk.

While the Ukrainian people have for the past month been defending their country from an atomic superpower, the western cultural community has been discussing whether to break ties with Russia. One might ask who is the more exhausted. Western intellectuals are looking for good Russians to ‘save’ from bad Russia – perhaps because ‘saving’ Ukrainian artists is much more difficult.

Although Wikipedia says I’m an ‘award-winning Ukrainian novelist’, I now spend my days volunteering in a humanitarian aid warehouse in Lviv. However, I cannot help but note the irony of these ‘rescue operations’.

For instance, after dancing for the murderous Russian elite for years, Russian ballerina Olga Smirnova suddenly denounced the war and left Russia to dance with the Dutch National Ballet instead.

Unlike her, Ukrainian ballet star Artem Datsyshyn died after Russians bombed Kyiv. You won’t see him on stage.

After producing fake news defending Russian aggression for years, the Russian propagandist Marina Ovsyannikova suddenly appeared on screen for a few seconds with a poster saying ‘No war’ and got millions of supporters.

Ukrainian journalist Oleksandra Kuvshinova died when Russian fire struck her vehicle on the outskirts of Kyiv, where she was risking her life to report the truth to the world. You won’t see Oleksandra on screen.

After writing books full of imperial sentiment that whitewashed Russian history and inspired yet another mass murder of Ukrainians, Russian authors would like to be seen as belonging to ‘Another Russia’ and garner the world’s support. But are authors like Boris Akunin ready to stop promoting the Russia-centric view of eastern European history and to acknowledge that Crimea indisputably belongs to Ukraine and its native Crimean Tatar people, who are part of the Ukrainian political nation?

In contrast, the film director and former political prisoner Oleg Sentsov, himself from Crimea, and the novelists Artem Chekh and Artem Chapaye, are currently risking their lives serving in the Ukrainian Armed Forces. The poet Serhiy Zhadan remains in besieged Kharkiv to support his fellow citizens. Many more Ukrainian writers have undertaken the long, dangerous journey to the western of the country after spending weeks in cellars and bomb shelters with their children. They have all witnessed something they cannot yet describe or even remember clearly; they are still too disoriented by the apocalyptic scenes full of the dead bodies of their neighbours.

And yet, we repeatedly get invitations to participate in Russian–Ukrainian discussions about peace. Not only must we witness the mass murder and destruction of our Ukrainian heritage, but also, on the side, the debate about whether the world should cut cultural ties with Russia.

I have nothing to add to this Russia-centric discussion; I just want it to stop.

*

The debate on boycotting Russian culture is not what western artistic and intellectual circles should be worrying about now. At least not if they have anything to do with Europe and its values of human rights, dignity and solidarity.

Because while the world debates whether to cancel or to welcome artists and writers who suddenly feel like leaving Russia amidst its economic collapse, it neglects the crucial question: will Russia succeed in executing Ukrainian culture once again?

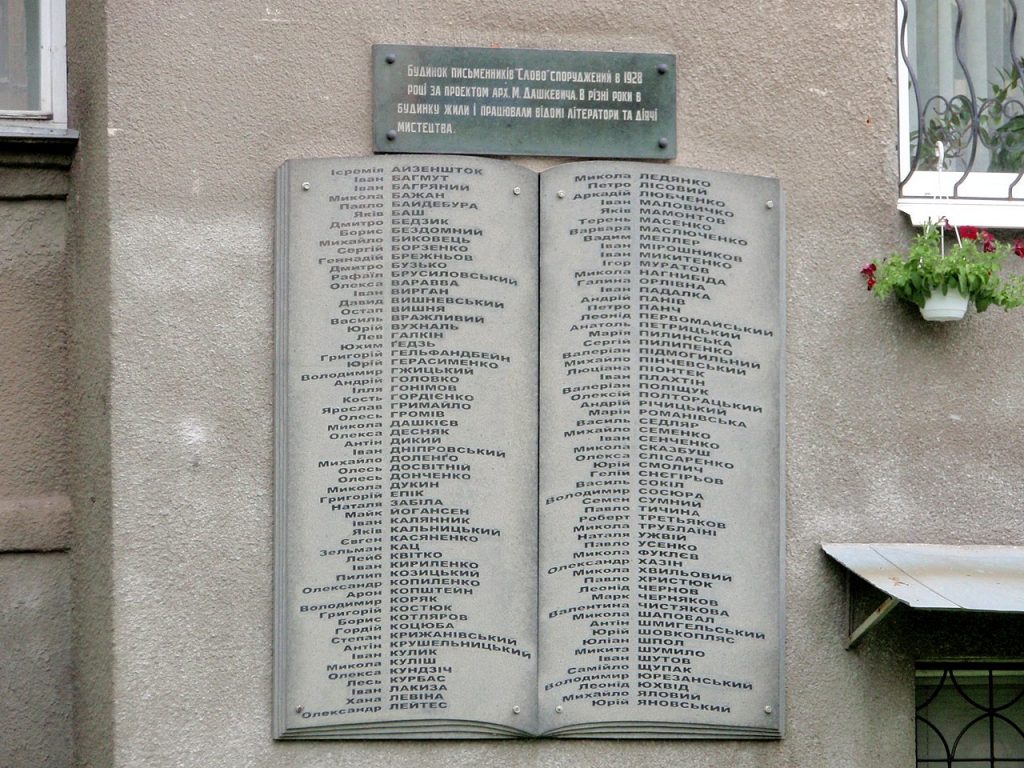

Before the full-scale invasion, when the threat was already in the air, I kept thinking about Ukraine’s Executed Renaissance. In the 1930s, the Soviet-Russian regime murdered the majority of Ukrainian writers and intellectuals. The few that survived were scared and unfree. And this, of course, wasn’t the first time the Ukrainian elite had been erased or forced to assimilate to Russian imperial culture.

The purges and centuries of unimaginable pressure are why you don’t often hear about great Ukrainian literature, theatre and art. When you look at the map of Europe, you see Dante here and Shakespeare, but only a vast gap where Ukrainian culture should have been to make Europe whole and safe.

Now there is a real threat that Russians will successfully execute another generation of Ukrainian culture – this time by missiles and bombs.

For me, it would mean the majority of my friends get killed. For an average westerner, it would only mean never seeing their paintings, never hearing them read their poems, or never reading the novels that they have yet to write.

‘Manuscripts don’t burn’, says the devil in Mikhail Bulgakov’s Master and Margarita. The devil then turns to his servant, a cat, ‘Come on, Behemoth, let us have the novel.’

Russian manuscripts don’t burn; that might be true. But Ukrainians can only laugh bitterly. It’s imperial manuscripts that don’t burn; ours do.

Have you ever read The Woodsnipes by the Ukrainian writer Mykola Khvylovy? Nor have I. And the devil from the Russian book won’t help us out. Russians destroyed the second part of Khvylovy’s manuscript, confiscating all the copies of the Ukrainian magazine that featured it. Not a single copy was ever found.

The magazine was confiscated in 1933, the same year that Khvylovy died in Kharkiv. At that time, Ukrainians around the city had had all their food confiscated by the regime. Millions died in the Holodomor, which is now recognized as a genocide. The ‘lesser’ crime of confiscating the magazine and destroying another work of Ukrainian literature went unnoticed for years. Most of those who would know about it were executed.

Plaque commemorating residents of the Slovo Building in Kharkiv, where many of the writers murdered in the Executed Renaissance had lived. Source: Wikimedia Commons

*

Ukrainian lives, paintings, museums, libraries, churches and manuscripts do burn. They are burning now.

So maybe it is time to shift the debate from whether the world should ‘forgive’ Russian imperial art and literature, to how to prevent one of Europe’s cultures from becoming another Executed Renaissance.

I was never a fan of Cancel Culture. But maybe the Execute Culture that Russians have repeatedly practiced on free Ukrainians is something the world would like to stop before it’s too late again.

Published 31 March 2022

Original in English

© Victoria Amelina / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTIn collaboration with

In focal points

Newsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Related Articles

Ukraine faces its greatest diplomatic challenge yet, as the Trump administration succumbs to disinformation and blames them for the Russian aggression. How can they navigate the storm?

Mineral rush

Topical: Critical raw materials

Why does peace in Ukraine hang on a ‘mineral deal’ whose handling is more reminiscent of trade than negotiations? Perhaps because the global race for critical raw material mining is well and truly underway, digging for today’s equivalent of gold: raw earth elements and lithium critical for renewables and digital technology but also modern weaponry.