While China moves into its fifth decade of extracting rare earths and raw materials, Europe remains stuck between nationalistic industry priorities and democratic principles.

Social media’s commercial colonization of the internet is clearly detrimental to the public interest. However, calls for an ‘information commons’ go too far: rather, those who own the new information channels must comply with rules set by democratic process.

Under what conditions may civil society effectively assert itself against great concentrations of power and wealth? When is democracy, rule by the people, possible? Dan Hind’s analysis of the role of media regimes in structuring the scope and boundaries of permissible discourse brilliantly exposes the ways how Big Tech platforms like Google and Facebook are conforming to the old demands of power. Meet the new boss, same as the old boss. But I question whether the answer he offers – ‘a public platform architecture that is transparent, secure and governed directly by those who rely on it’ – centres our attention where it is most needed.

Consider Wikipedia, the global encyclopaedia that is open to anyone to edit, which is the only non-profit website that ranks in the top 10 most visited in the world. It is all the things that Hind wants: a public platform, transparent in its operations to a fault, relatively secure (though I’m sure its system administrators might disagree), and governed by its contentious pool of volunteer editors and a non-profit board. Many of us believe it is the closest thing that we have online to public infrastructure, like a public library or park open to all.

Unfortunately, Wikipedia isn’t supported by public dollars, but thanks to its huge base of small donors it has never succumbed to the pressure to surveil its users and monetize their data. At the same time, despite recent efforts to recruit more women, close to nine in ten of the editors of the English-language version are male. Disputes about its governance are endless, suggesting that, as Oscar Wilde once said about socialism, the problem is that it would take too many evenings.

Or take the governance of the internet itself. In the early years of the net, the Internet Engineering Task Force, an open international community of network designers, engineers, vendors and researchers that anyone could join (and still can). They took it upon themselves to develop the standards and protocols that allowed a ‘network of networks’ to organize itself and spread. An eco-socialist like Hind would probably have loved these engineers, one of whom memorably declared: ‘We reject: kings, presidents and voting. We believe in: rough consensus and running code.’

When the neoliberal Clinton-Gore administration made the fateful decision to allow the commercialization of the Internet, based on the mistaken belief that government couldn’t and shouldn’t shoulder the costs of expanding the underlying communications infrastructure to meet the rising demand for its use, we lost something very valuable. Indeed, after one commercial operator was given permission to start carrying commercial traffic on the internet, a competitor complained that this was the equivalent of ‘giving a federal park to Kmart’. Since then, market forces have taken over the internet in exactly the same ways one might picture what could happen if, say, the Trump White House decided to privatize Yosemite.

So, I’m all for the revival and expansion of truly public digital infrastructure. I am deeply worried that in the last two decades, we have unwittingly allowed a new breed of robber barons to colonize the once virgin lands of our own minds and behaviour, handing out promises of unlimited information and conveniences like so many pieces of wampum. But unlike Hind, I’m not sure we need that infrastructure to be ‘governed directly by those who rely on it’. To extend the analogy, most of us probably don’t want to be directly involved in governing how our subways work or how our schools are run.

Rather, what I would argue is that the people who run those systems should be governed by rules set through democratic processes. The problem is not that our media is undemocratic, it is that our government is undemocratic. Finance has almost completely captured politics, and philanthropy has almost completely contained advocacy. All that is left is how we organize ourselves.

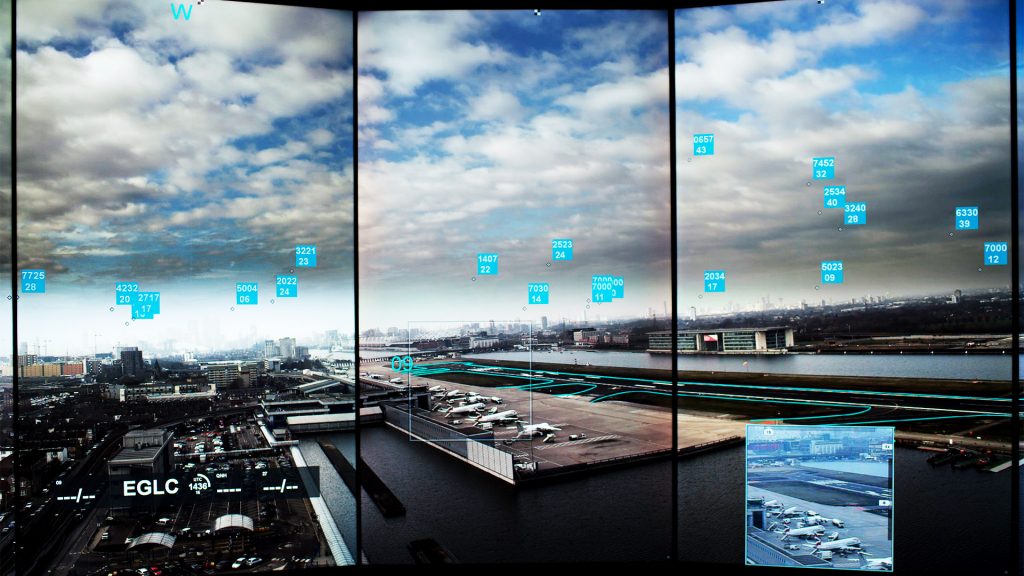

Photo via @natspressoffice from Flickr

Published 4 February 2020

Original in English

First published by Public Seminar

Contributed by Public Seminar © Micah Sifry / Public Seminar / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTSubscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

While China moves into its fifth decade of extracting rare earths and raw materials, Europe remains stuck between nationalistic industry priorities and democratic principles.

The race for green transition supplies is on. But where’s the thrill in metals, discreet and hidden yet widespread? Mining, intensive due to low concentrations, throws up waste elements like arsenic. Space cowboys and deep-sea dredgers contest environmental stability more than China’s monopoly, based on 40-years of involved processing. Health and recycling regulations are a must.