Up until the end of March of this year, practically everyone thought surveillance was about two things: terrorism and advertising. And for most of us that was OK. Who cares that I’m being watched if they’re doing it to show me ads for things I’m interested in? I have nothing to hide, so why does it matter?

Then, at the end of March, a twenty-nine-year-old Canadian with pink hair and thick rimmed glasses added a new variable to the equation – one that few had considered until then: soft surveillance could be used to destroy democracy. Or, at the very least, to get a large number of citizens to support policies detrimental to their society.

According to Christopher Wylie, Cambridge Analytica used the personal data of millions of users to influence at least two electoral processes. After helping win the Brexit vote, they established themselves as a company with the support of Robert Mercer, a billionaire hedge fund manager and one of two fortunes behind Donald Trump’s presidential campaign – the other being Peter Thiel, the man behind Palantir.

In his testimony in front of a British parliamentary committee, Wylie explained that everything began with a test called ‘This is your digital life’. Designed by Cambridge psychology professor Aleksandr Kogan, it was based on the popular OCEAN model, which evaluates an individual’s personality based on five main traits: Openness (to new experiences), Conscientiousness (responsibility), Extraversion, Agreeableness, and Neuroticism (emotional instability).

The model is popular because it measures characteristics that transcend culture, fashion and locality. It works the same in Paris and in Alaska, in the 1980s, or today. At first, Kogan published the test on two platforms that provided micropayments to test-takers: Amazon’s Mechanical Turk and Qualtrics, a market research company. The test included 120 questions and users were paid between 2 and 4 US dollars to complete it. It was slow going until Kogan decided to upload it to Facebook, where personality tests at the time were viral material.

On Facebook, Kogan found 270,000 people willing to take the test. The terms and conditions, which no one read, said ‘By clicking OK, you give us permission to share, transfer, or sell your data’. On top of giving unrestricted access to all the data associated with a person’s account, such as their marital status and religious affiliation, it also granted access to every account on their list of friends. This was very good for the project – even though Kogan claimed the goal was to study the use of emojis to express emotions, in reality the test was designed to build a predictive algorithm of psychological behaviours. Facebook gave Cambridge Analytica two databases needed to do this: one dataset with the specific characteristics it was trying to predict, known as a feature set, and another with the variables about the people for whom they wanted to predict these characteristics, known as target variables.

Facebook later accused Kogan and his partners of breaking the developer agreement they signed when they uploaded the app to the platform. The agreement said that user data cannot be commercialized, but it also said that Facebook audits and monitors all applications to make sure they comply with the terms of service. The test was on the platform for a year and half, until Kogan himself removed it. In fact, using tests and quizzes to vacuum up large amounts of user data had been a popular practice since at least 2009, when numerous civil rights groups denounced Facebook for doing it. Kogan’s test was uploaded in 2012.

Moreover, three years later Facebook redesigned its API – the tool that mediates between external app developers and the platform – so that it was still possible to collect user data and other types of information. Kogan also had access to users’ private messages. As programmers say, this ‘misuse’ was not a bug or an abuse of the system – it was a feature. Facebook earned thirty per cent on all operations without asking what the data was for or who was collecting it.

Facebook estimates that there were 87 million affected users, an average of 300 for each person who took the test. But Cambridge Analytica is just one of the hundreds of thousands of agents who took advantage of the opportunity Facebook presented at the expense of the privacy of billions of people.

Mark Zuckerberg F8 2018. Source: Flickr

How to get voters

It would be an exaggeration to say that the elections of the most powerful country in the world were hacked with a personality test, but the plan was subtler than that. It was not about manipulating the entire electorate (200 million people) and getting them to vote for Trump, but about modelling the electorate with 4,000 to 5,000 data points (including the test but using other sources as well) to find up to 5 million people with a high degree of neurosis.

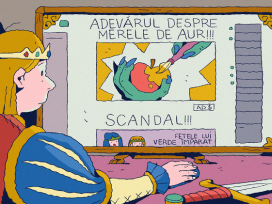

Neurotics are particularly susceptible to conspiracy theories. Cambridge Analytica would use the predictive algorithm to find the most vulnerable citizens and exploit a very specific vulnerability: fear of the poor, hatred of black people, environmental anxiety, rejection of vaccines, and paranoia. Once this segment was located, they could bombard it with targeted disinformation. Disinformation campaigns are nothing new, however with the internet they have become a lucrative service industry. Cambridge Analytica did not have to get its hands dirty running the campaigns themselves – they could outsource them.

Facebook is the king of political marketing. The platform isn’t only designed to extract as much information as possible from its more than 2.2 billion users. There’s an additional side to the business: it is a highly precise micro-targeting platform. This allowed Cambridge Analytica to select its targets depending on how vulnerable they judged them to be. An example: in 2016, Propublica discovered that Facebook had configured the system to be able to segment neo-Nazis, white supremacists and Holocaust revisionists for specific campaigns.

A little earlier, Facebook had been denounced for selling a cosmetics company packages of data about teenagers with self-esteem problems. Then there are the fake news agencies, which are like real agencies but designed to produce counter information, misinformation, or simply generate noise and chaos around a specific event, company, product or individual. The most famous is the Macedonian operation whose successes include starting the rumour that Obama was not a US citizen (which brought about the movement demanding him to show his birth certificate) and that Pope Francis supported Donald Trump (which is still one of the most clicked-on stories in the history of the internet).

‘One could make people believe the most fantastic statements one day, and trust that if the next day they were given irrefutable proof of their falsehood, they would take refuge in cynicism,’ Hannah Arendt wrote in The Origins of Totalitarianism. ‘Instead of deserting the leaders who had lied to them, they would protest that they had known all along that the statement was a lie and would admire the leaders for their superior tactical cleverness.’

In addition to Facebook and Twitter, the favourite platforms of disinformation agencies have been Instagram and YouTube. And they have not always needed to produce news. In a context of overexploited and understaffed newsrooms that have sold out in pursuit of low-quality viral content and page rank, they often only needed to place their content strategically. The Trump campaign sent African-American Democrats a video of Clinton in the 1990s talking about blacks. The message: Obama’s successor is not only white, but she’s actually closer to the KKK than to Black Lives Matter.

Among the trolling agencies, the most famous is the Internet Research Agency, linked to Russian president Vladimir Putin and based in St. Petersburg. But there are others in China, Venezuela, Indonesia, Mexico, Puerto Rico and elsewhere. Their usual tactic is to activate a swarm of bots, in other words hundreds of social media accounts controlled by a human. Trolling agencies are basically call centres: they work on demand and volume is key; they can just as easily be used to review a product as to attack a political opponent. New political marketing campaigns use all these resources to create a sort of ‘weather system’ around a subject, a party or candidate.

Unlike traditional political marketing, which is based on such things as banners and rallies, the key to this new approach is that it doesn’t look like propaganda – it takes the form of information. It targets people with specific vulnerabilities and wraps them in a bubble of targeted content across multiple social platforms, creating an alternate reality that is contrived with a specific goal in mind. We don’t have enough data to know with certainty if this strategy is effective, but we do know it could work, and that it apparently did with Brexit and Trump.

Hacking elections

This approach wasn’t new however. Long before the Cambridge Analytica scandal broke, J. Alex Halderman and Matthew Bernhard, experts in electoral security at the University of Michigan, explained that the best way to fight an election campaign was not to try to convince all voters, but to pour all of one’s resources into the single place where they might have the greatest impact.

According to Halderman and Bernhard, there are three ways to hack an election. You can prevent people from voting using a denial of service attack or you prevent the votes from being counted. Both things happened in Ukraine in 2012. You can also contaminate the political landscape by producing information that is damaging to a specific candidate, for example by publishing the Democratic Party emails that revealed that Clinton had conspired to manipulate the primaries against Bernie Sanders. This is aimed at hurting one’s political opponents.

Lastly, the election results can be changed. The system is designed to prevent this happening, but it is possible. To do it mechanically, you have to alter the votes. This is practically impossible with paper votes, but the US uses electronic voting machines. Technically, the machines are not connected to the network, but they are programmed by other machines that are. If these can be rigged to transmit the right kind of malware to the voting machines, it can be done.

According to Halderman and Bernhard, it doesn’t make sense to hack all of the machines, only the ones you need to win. Find the states where the difference between the two candidates is below one per cent and those that are most relevant by representation (typically, swing states like Michigan, Pennsylvania, Florida and Wisconsin). Then, out of all the companies that service the voting machines in those states, find those with the fewest resources and attack them. These companies are the equivalent of the highly neurotic, vulnerable individuals Cambridge Analytica identified online. The strategy is the same.

Wylie said their conversion rate was between five and seven per cent. The Kogan test was just the beginning of the project, but they needed more data to go further. To obtain it, Cambridge Analytica debuted in the Ted Cruz campaign. There, they obtained the voter database Facebook couldn’t supply them, a brilliant strategy by Robert Mercer, who since then has given financial support to all kinds of Republican causes, always on the condition that Cambridge Analytica be part of the package, keeping all the necessary data to feed, test and refine their algorithms.

Between Cambridge Analytica, now re-founded as Emerdata, and Palantir, Donald Trump has the two most powerful behavioural prediction algorithms on the planet at his service. Trump runs for re-election in two years. Peter Thiel has already said that he is moving to Los Angeles to start a media empire.