Zbigniew Herbert is one of those writers that everyone has heard of but very few have read. People in central and eastern Europe had high hopes that he might win the Nobel Prize in Literature, but it never happened. Perhaps it was because two Poles (Czesław Miłosz and Wisława Szymborska) were already awarded the prize during that period. Be that as it may, twenty years after the writer’s death, it is worth looking back and examining this outstanding figure from a different perspective: as a deep poet, a sophisticated essayist, a profound thinker, a dissident and an eastern European barbarian who saw the garden of western culture in his own way.

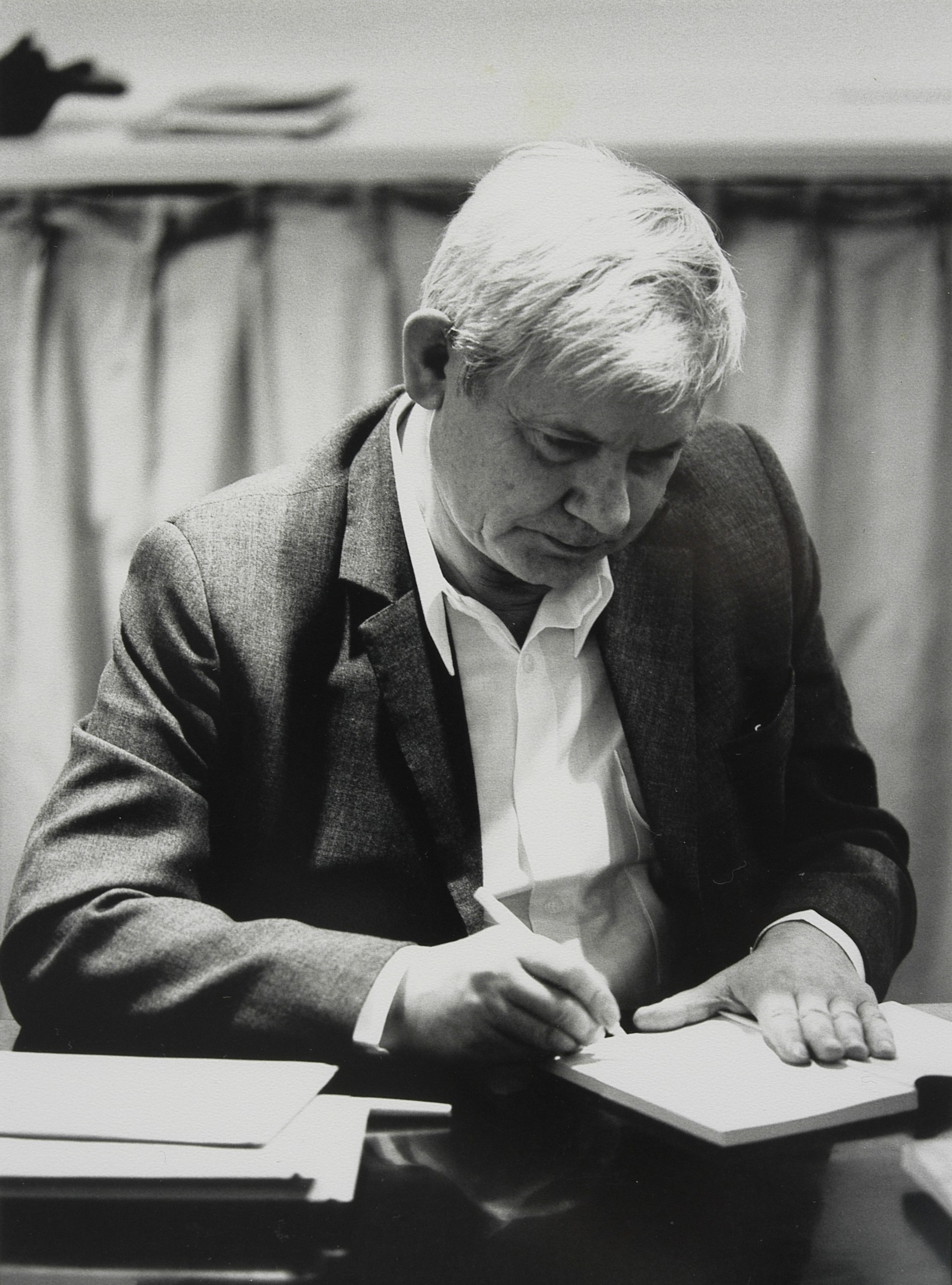

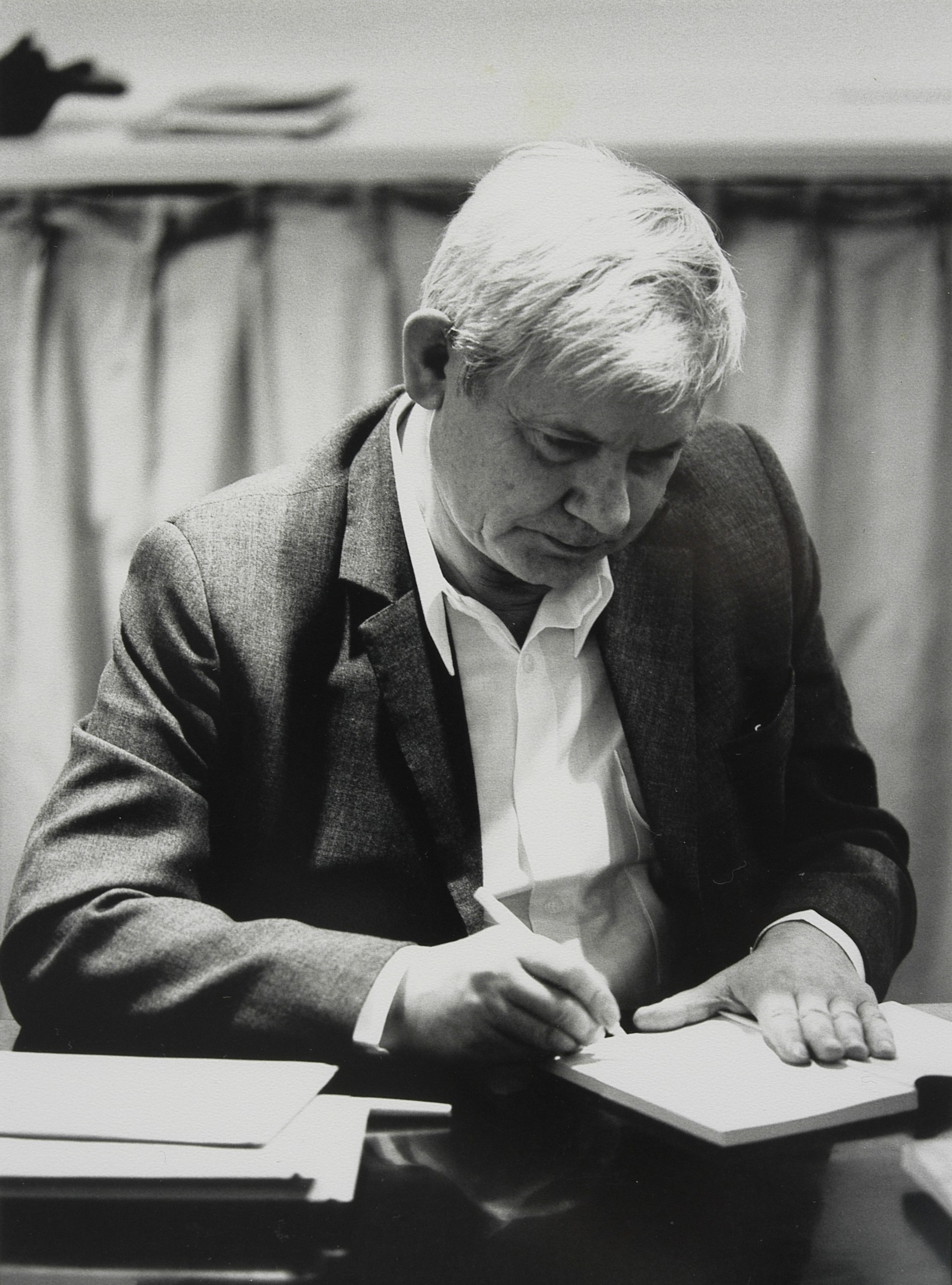

Zbigniew Herbert signing one of his volumes of poetry in Paris, 1989. Photo: Archives of Zbigniew Herbert/ National Library of Poland.

Hailing from Lviv

The future poet was born on October 29th 1924 in Lviv, the city of many peoples and cultures. Multiculturalism in his childhood shaped Herbert’s way of thinking – later, mono-ethnic Poland was boring for him and in 1990 he requested his honorarium for a book of poems, Elegy for the Departure, to be transferred to the Ukrainian Lyceum in Legnica. After all, he himself came from a family with English and Armenian ancestry who, by a twist of fate, first moved to Vienna and then relocated to Lviv.

Herbert’s family was rather wealthy. His father was a bank manager, so Zbigniew had a carefree and financially secured childhood. During the Soviet and Nazi occupations the future writer, although illegally, continued his studies. In 1943, the crucial year of the war, Herbert received his matriculation certificate and enrolled in the underground studies of Polish philology. In 1944, before the Soviet Union re-occupied Lviv, he left for Kraków.

This was the beginning of another chapter in Herbert’s life. He left Lviv to be the master of his own fate. In Kraków, Herbert began to study economics, only to transfer to law at the University of Toruń three years later. He also began reading philosophy there, but was forced to break off his studies as his family moved to Sopot on the Baltic Sea coast. Later, after moving to Warsaw, Herbert continued to study philosophy at Warsaw University. This would suggest he was interested in many fields of study, and that his intellectual horizon was formed in universities. However, this is only partially true: in fact, his patchwork and impermanent learning – due to the war, the occupation and frequent relocations – taught Herbert to rely on self-education. He learned this lesson well and would master whole areas of knowledge, systematically collecting libraries on different topics.

The first significant collection of Herbert’s poems was published in 1950. This could be called his entry into literature, but in reality it was not: he decided not to mix writing and politics (social realism), so the door to the literary world in communist Poland was closed. He had to take every opportunity to make a living: by working at a disabled community, at industrial plants, as a teacher, and as a bureaucrat at the Union of Composers. There was also a time when he earned money by regularly donating blood. This is how the Polish writer Leopold Tyrmand described Herbert at the time: ‘He cultivates moral purity, an uncompromising attitude and fidelity to himself a little ostentatiously, but so honestly that one cannot find fault with him, nor pay him anything but deep respect. Of course, he lives in poverty. He earns a few hundred zlotys per month as a timekeeper in a co-operative that produces paper bags, toys and boxes. The calmness with which he endures, this drudgery after receiving three degrees, is straight out of early Christian hagiography.’

Nevertheless, the dream of literature and making a living as a writer never left him; he often wrote reviews, articles, and reports for various publications. Writing in what seemed like simple genres, he was able to remain honest to himself as a writer and wrote about art, evaluating it by aesthetic and not the Stalinist criteria.

Post-Stalin

Gradually Herbert became acclaimed in literary circles and made useful connections which eventually helped him get on his feet. The oppressive censorship of the communist dictatorship in Poland, however, precluded him from fully developing. It even reached the point that, in 1951, he was forced to leave the Union of Writers – though only for a short while. In 1955, as the political climate in Poland changed, he re-joined the Union, which at the time opened a door to his writing career. In 1956, after Stalin’s death and the beginning of the thaw, his debut book of poetry, Chord of Light, was published.

As clichéd as it may sound, the morning after it was published Herbert woke up famous and his life had changed forever. Although Herbert was one of those artists who achieved success through years of hard, systematic work and honing his talent, his debut book had a positive impact on his situation. Shortly after its publication he received a tiny apartment, his first private space where he could concentrate on reading and writing. Favourable reviews, membership in the Union of Writers and the reputation of a decent person all contributed to the fact that in 1958, he received a scholarship and set off on his first travel abroad.

Later, such trips, scholarships and residences would become so abundant that they could be called a kind of emigration. Only at the end of his life had Herbert permanently settled in one place – Warsaw. Prior to that, he spent most of his life travelling, staying in hotels and boarding houses. Travelling was both his passion and a form of self-education. He studied the world around him, seeking diversity and a constant change of scenery. His wife, Katarzyna Herbert, recalled: ‘When he visited some sight, nothing else was of interest to him. It did not matter whether he had eaten or had enough sleep. Travelling with Herbert was extremely exhausting. I was hungry, but he did not want to waste time eating. He always planned a detailed route of a journey and would not stop for a moment. Yet travelling with him was a wonderful experience. He was looking at everything in such way that I never saw later. He learnt how to look at art. Because one should learn how to do this. At the Uffizi Gallery in Florence he would return to the same pictures several times.’

This wanderlust could be called an addiction; modern psychology even created a term for it – dromomania. But there was another side of his addiction – a political one. The truth is that Herbert felt suffocated in communist Poland; he was lacking a creative atmosphere. On the one hand, travelling inspired him and offered him an opportunity to write on a variety of topics beyond social realism; but on the other hand, he simply could not live without Poland. He disliked communist Poland, it was hideous for him, but it was still Poland – his homeland – and one does not choose one’s homeland. The poet wrote in one of his letters: ‘I am going back to Poland in a few months. It will be like getting into dirty and cold water, but this is my only reality. I live here on the surface, without any sense or reason.’

Emigrant, exile, tourist?

This situation is manifestly ambivalent. Herbert cannot be called an absolutely anti-regime artist, because he lived in Poland, his books were published there, and he was a member of the Union of Writers, which granted him scholarships for travelling abroad. In spite of that, Herbert was an anti-communist in his writings, though he did not manifest this with political slogans, nor did he speak publicly about it.

Why was he an anti-communist? First, because of the style and topics of his work. He wrote like a sophisticated classical author, and this contrasted sharply with the social realist dogmas of the time. Second, there was something encrypted in his poems – particularly in the legendary collection of poems about Mr Cogito – an intellectual mystery and noble charm which enabled readers to discover hidden meaning in writings. And that hidden meaning was anti-regime. Third, Herbert often found escape in the themes of his writings: since he did not want to write about collective farms, milkmaids and tractor drivers, he set off on his travels to write about the Mediterranean and the major achievements of western civilisation.

This was a double escape for Herbert. First, it was an ‘internal emigration’: writing for himself and a close circle of people, writing on geographically and historically remote topics, and writing in the so-called Aesopian language that was accessible only to a very few insiders. Second, his travels abroad were so frequent and long (often lasting for several years) that they might as well be called emigration – or even exile. Over the years, Herbert’s popularity grew rapidly in Poland and western Europe, and in the 1960s there were voices in Germany calling for him to be awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature. The regime in Poland tried to gain his favour with scholarships and permits for foreign travel, seeking to win Herbert’s loyalty, but they failed.

However, we should not be under any impression that Herbert indulged in luxury or travelled like a superstar. On the contrary: he was very modest and unpretentious, someone who can be compared to present-day backpackers who stay in hostels and buy wine in shops rather than restaurants. His first scholarship (for his trips abroad in 1958 and 1959, when he visited Austria, France, England and Italy) was for only 100 US dollars a month. Before leaving, Herbert had to write to several editors asking for his honoraria to be paid in advance, appealing to their sympathy with stories of sudden illness. In one letter, he wrote: ‘Now I am travelling in France, I climb on the cathedral towers, and my life is like a dream. I have extended my stay here to September, and if I have enough money, I will hitchhike to the Mediterranean Sea. I am exhausted but happy that I can see so much.’ The writer who was expected to win the Nobel Prize was happy as long as he had enough money for museum tickets, cheap accommodation and a glass of dry wine.

Herbert was primarily an aesthetic dissident rather than a political one. After the communist archives were declassified, it was revealed that the western intelligence services had attempted to enlist him. Herbert refused. Later, because the communist intelligence viewed such a refusal as an act of loyalty, the Polish services also tried to enlist him. Herbert refused again and tried to make this matter public, which could protect him from further pressure. He remained a noble-minded intellectual who knew the power of his poetry and realised that it could erode the system. He aspired to be a writer who wrote on lofty topics, and to live honestly and with dignity, avoiding the mud and the primitiveness of daily politics. However, he did not succeed to the end.

Report from the besieged city

In late 1981, General Wojciech Jaruzelski proclaimed martial law in Poland – anxious that the popularity of the opposition movement Solidarność was growing. At this time, Herbert was living in Warsaw and was not only a witness to those events but also an influential participant. He seemed to personify the character of the romantic revolutionary poet who led the people’s uprising. Herbert’s creative response to martial law was the classic collection of poems, entitled Report from the Besieged City, which was originally published in Paris and later printed illegally in Poland. People hand-copied poems from this volume, some typed them on typewriters, others learned them by heart and some poems even became songs. During this period, Herbert’s popularity reached its peak in Poland and he became a truly national poet.

The title of the volume itself is interesting, since it turns to the origins of western civilisation, centring on the fundamental archetype of the city and the barbarians surrounding it. Like his best-known novel Barbarian in the Garden, the eastern European travels to the most important sites of western civilisation. Remarkably, Herbert writes the word ‘city’ with a capital letter, as if he is speaking of Ancient Rome. To some extent, Herbert can be compared with Ovid, who was banished by Emperor Octavian Augustus to the Danube Delta – the edge of the civilised world. Ovid and Herbert complement each other, the only difference being that Ovid considered himself to be civilised and was exiled to the East, while Herbert created his self-image of a barbarian who rediscovered the cultural treasures of the West.

In Report from the Besieged City, he takes the role of an ancient chronicler describing tumultuous events. However, every reader knows he was writing about contemporary Poland and the communist ‘siege’. These poems are laced with allusions to the earlier siege – the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, on whose basis Lviv, Herbert’s native city, was occupied by the Soviet Union. Though the volume is somewhat pompous, it nevertheless seems natural, since those poems were written with the thoughts of barricades and rallies. Report from the Besieged City brought Herbert true fame, one achieved by very few poets in history, but he had to pay a heavy price for it in the decade that followed.

Oblivion and Glory – Again

After the fall of communism, Herbert’s popularity faced the same fate as other anti-communist artists. They were quickly forgotten as the new generation – the generation of freedom – took centre stage. People cared little about the dissidents, the heroes who fought against the regime, their Aesopian language and poems with double meaning. After the fall of communism, a dissident poet was unnecessary for society, like a soldier after the war. Heroes are born in uprisings and revolutions, but no one needs them in everyday life. To make matters worse, Herbert suffered from depression for decades, and his health deteriorated near the end of his life. His last works are imbued with frailty of the human body and the phenomenon of physical pain.

Fortunately, Herbert’s work was revived by the next generation – the generation that did not remember communism and martial law, and thus did not consider his poems political. It was the new generation that rediscovered Herbert as a poet and philosopher, a profound intellectual, and a world-class essayist. He regained popularity after his death and his works were re-printed in Poland and abroad. In 2013 Herbert’s family and a group of his admirers established the Zbigniew Herbert International Literary Award, which aims to promote his name around the world. However, no prize could promote Herbert more than his own thoughtful, sophisticated and memorable works.