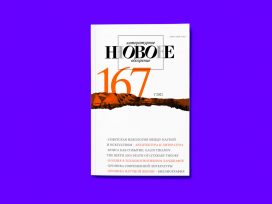

Russian journal ‘New Literary Observer’ focuses on the utopianism of the Soviet avantgarde: why ’20s architecture remained on paper; on urbanist versus de-urbanist futures; and how memorials constructed memory in real time.

What Ilchenko calls the ‘architecture of the word’ referred not to a tangible, material product but to a profoundly utopian project for buildings and cities of the future. He argues that ‘the architecture of the avant-garde and the word (slovo) are inseparable from each other, while the way of talking about the avant-garde is as significant as actual architectural projects themselves’.

Urbanization versus de-urbanization

The utopian theme is taken up by Mikhail Timofeev in his article on representations of the city of the future in two short stories from the 1920s – Alexei Chayanov’s The Journey of My Brother Alexei to the Land of Peasant Utopia (1920) and Vladimir Fedorov’s The Miracle of the Sinful Pitirim (1925). These two fictional accounts are compared to illustrate debates between urbanists and proponents of de-urbanization in the early Soviet period.

Again, the very public discussions of the cities of the future took place in stark contrast to ‘the unchanging material environment’. Chayanov’s story describes the bucolic idyll of a de-urbanized Moscow in 1984. This image would prove not only unrealistic, but against the Party line formulated in the 1930s (Chayanov was arrested in 1930). On the opposite end of ideologically spectrum was Fedorov’s dynamic and hyper-industrialized city of Ivanovo-Voznesensk, imagined from the perspective 2025. Though politically correct, it proved to be no less of a pipe-dream.

Imaginary memorials

Moving from future visions to memories of the past, Vadim Bass focuses on Soviet war memorials. We usually think of memorial architecture as being dedicated to the preservation of significant events and figures of the past, however as Bass argues they are as much a reaction to the immediate present.

Bass looks at monuments to the Second World War designed during the War itself. Again, the focus is not on the works themselves, but on the discourses that emerged around them. As Bass says, ‘the most impressive designs remain on paper’. One example is the all-pervasive image of the Palace of the Soviets, which was presented at World exhibitions, in cinemas and in other propaganda media. The fact that no such building actually existed did not affect its status as a ‘fact’. In a sense, Bass argues, all Soviet architecture was constructed ‘in the shadow of the Palace of the Soviets’.

This article is part of the 3/2021 Eurozine review. Click here to subscribe to our weekly newsletter to get updates on reviews and our latest publishing.

Published 17 February 2021

Original in English

First published by Eurozine

© Eurozine

PDF/PRINTNewsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.