Historically, and especially since the beginning of the twentieth century, much of the avant-garde was founded on a programme of opposing the status quo, usually with the market as one of its targets. Yet eventually all such art has been historicized and commodified by the market, and by the power of the capital supporting it. The question is: how did these processes of historicisation and commodification work in the past, and how will they operate in the future? Does the market value of an artwork (sometimes intrinsic, sometimes entirely speculative) allow it to be historicized? Is it the other way round? Or is there an inextricable relationship between the two?

Until now, public and private collections were all that remained of entire movements, in a majority of cases surviving only because of the market value of the collection itself. With the art market’s strict materiality and its fundamental connection to objects and their uniqueness, only the ephemeral has been lost: performances, conceptual and electronic artworks. Yet these can also now be retrieved through relics, documentation and physical pieces of these movements’ greatest periods, as well as their more recent artworks (where they are purposefully more physically conceived). But the current instability of the global market poses a more exciting question: will the instability affecting every economic sector also begin to affect the contemporary art market and its superstars? Will works by Hirst or Cattelan be hit by the recession and fall substantially in value, no longer being an “investment”?

If we’re facing not only an economic crisis, but the latest mutation of the capitalist beast, then perhaps we should abandon all certainties. In these uncertain times, those best suited to engaging with the situation are the artists themselves; having the skills to play with reality and its more ethereal aspects. Artists, after all, have envisaged in the past some of the elements that are currently driving huge change.

The network and the copy

Two elements seem to have significantly contributed to this change: the network, and the technical means to make infinite copies of an artwork. The network has an important precedent in the art subcultures that flourished in the 1980s and 1990s: the “Mail Art” movement. In a famous drawing published on the cover of Real Correspondence – Six in 1984, Vittore Baroni, a historian and one of movement’s pioneers, drew an historical line between art before and art after Mail Art. He depicted a manifesto which reclaimed the independence of an underground art phenomenon that used multiple strategies to free itself from the shackles of the market. Yet when studied closely, the basis of this reclaimed cultural difference was not a defined strategy, nor an affirmation of the right to allow audience and artist to switch their roles, but rather the existence of an active, expanding and ethereal “network”.

Artists do not stand alone, and are no longer singular geniuses; they collaborate (mainly trying to affect or construct mass media products), and they are “connected”, both with each other and directly with the audience. A decade later, the network as we now know it (the Internet), began to connect private and public spaces, and was able to explode the limits of connectivity. In a couple of years the “Net.art” movement gave a new spin to the de-materialization of artworks, with a performance approach; it produced artworks shared directly with online masses through the changed communication rules.

Cosic’s “Net.art per se” – the movement’s manifesto – posed the open question, asked in a spirit of pioneering enthusiasm: “Is hard copy obsolete?” The movement was experimenting with a new medium, and fervently challenging the rules of the elephantine market structure. Nevertheless, in a little over ten years the situation evolved rapidly and was turned almost upside down. Cosic was one of the leading artists in the recent “Holy Fire” exhibition at iMal in Brussels, which attempted to take an important evolutionary step by exhibiting purchasable Net.artists’ works in a joint effort with galleries, collectors and the Art Brussels fair. The mandatory citing of Benjamin’s “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction” is only appropriate in this context for the “mass market” as it increasingly emerges from obscurity. In the attractive new art market, new collectors from emerging nations (Russia, Brazil, India and China, to name just a few) are changing the rules again, contributing to the spread of instability, interconnectivity, interrelationships, ethereal information and value. Doesn’t this sound like the network paradigm at its most excessive?

The Italian job: the value

Is there a reason that explains why, compared with other countries, Italy offers a different perspective on the relationship between art and money? Perhaps its artists have experimented with this art / price / money relationship because of the country’s stunning (and inestimable) art heritage, and the cultural influence that implies. In the 1980s, some high school teachers introduced children to art by telling them that “art is something not strictly useful and has no value other than beauty”. They seemed to have forgotten the lesson taught by Piero Manzoni some twenty years before. In 1961’s “Merda d’artista” (artist’s shit), Manzoni sold a few canned boxes, claiming that they contained only his own excrement, with a certificate and a date stamp on the label. Setting a price tag on the thing one should pay least for (shit), was one of the high points in the provocation and questioning of an art system based on established rules and tradition.

A few decades later, in 2006, another well known Italian artist exploited a similar concept, conceiving something similarly repellent in a unique example. During Art Basel, Gianni Motti sold his “Mani Pulite” (Clean Hands) work for 15,000 Euro. The work comprized a bar of soap, which Motti pretended had been made from Silvio Berlusconi’s liposuction fat. The artist claimed to have obtained it via an employee of the Swiss clinic where the Italian Prime Minister’s liposuction was carried out. “Mani Pulite” was actually the name of the famous Italian investigation and raid which exposed an entire corrupt political generation in the early 1990s, and marked the end of the first republic.

Corruption, politics and art are also all connected in conspiracy theories which speculate on the shady Italian “Transavanguardia” movement. Such theories attempt to prove that the movement planned to use the art market to establish a new business model solely for laundering money gained from political corruption – a major work of art in itself.

“Art, Price and Value” – a paradigmatic exhibition

Italy is also the host of the exhibition “Art, Price and Value, Contemporary Art and the Market”, held in the middle of a tremendous global economic crisis. It’s curated by the critic Piroschka Dossi, author of “Hype! Kunst und Geld” (Deutsche Taschenbuch Verlag 2007), and Franziska Nori, project director of the Centre for Contemporary Culture Strozzina, Florence (also the location of the exhibition). It’s an exhibition with a very wide scope, and is very different from being simply a reflection on the relationship between art and the market. Dossi explains that the exhibition unfolds between the conceptual art approach with its “paradoxical sale of something un-sellable” and the Warholian approach, where there is no difference between the artist and the entrepreneur.

Twenty-one artists are each in some sense defining distinctly different starting points for a potentially endless debate. Despite being anything but a mainstream exhibition, works are included by superstars Damien Hirst (the door of his cult club “Pharmacy”, which sold for an unexpectedly huge sum at Sotheby’s) and Takashi Murakami (his limited edition Louis Vuitton handbags).

Nevertheless, an artist’s value is not always such a simple matter, especially for those excluded from the star system. Perhaps most emblematic of this is Luchezar Boyadjiev‘s “GastARTbeiter, 2000-2007”, a triptych mapping ten years of work and documenting the value attributed to the artist through the course of his institutional projects. Taking the concept to an extreme was Michael Landy’s performance piece “Break Down”, where the artist systematically destroyed all of his possessions, including his birth certificate, his car and cherished personal effects. This is the negation of any value through its physical destruction, even where this value is symbolic or sentimental. Personal possessions are simply thrown away, or buried. This is a concept thousands of miles removed from the intoxication by personal possessions: the mall, that temple of consumption. Marco Brambilla’s “Cathedral” video instead celebrates this artificial paradise with a digital representation of a multi-level Toronto shopping mall during the Christmas season. The result is an ever changing vertical space of light and colour, as mesmerizing as a religious stained-glass window (indeed the screen itself is back-projected).

At the apex of the economy, the stock exchange represents the virtuality and volatility of capital, and at the same time its greatest expression in terms of the collective imaginary. The fate of entire economies is decided “there”; no hyperbole when you consider how Iceland’s whole economy was destroyed in a few weeks by the market crash. This “extra-territory”, where a few hours hectic activity, driven by so many unpredictable variables, is able to move astonishing amounts of money, has always tickled the artist’s imagination. Aernout Mik’s “Middlemen”, with its surreal “tableaux vivants” depicting scenes of stockbrokers, is a classic expression of this phenomena (and frighteningly prescient of the stock exchange crash, when made seven years ago). And where Claude Closky’s “Untitled (NASDAQ)”, is a wallpaper showing the flood of data generated by stock market activities, Fabio Cifariello Ciardi’s “A Bid Match” is a conversion across data domains (from stock values to sound) derived from Sotheby’s NYSE stock value on 15 September 2008 – the first day of the Damien Hirst auction.

Money is at the heart of Antoni Muntadas’s “The Bank”, with its brilliant idea of making 1,000 US dollars disappear via a series of currency exchanges. Money as we know it – the coins, but especially paper money – is also becoming volatile; Photoshop is preventing users from scanning and reprinting high-resolution copies of banknotes. The question is: would this be considered forgery or just illegal copying? Hackers have already worked out how to circumvent such technical restrictions, but imaginary money (the effortless multiplication of banknotes) persists. This is where Wilfredo Prieto’s “One Million Dollars” scores, with a dollar banknote “multiplied” through two parallel mirrors, but where Cesare Pietroiusti’s “Untitled” misses, attaching 3,000 sulphuric-acid-treated dollar bills to a wall, for the public to remove for free.

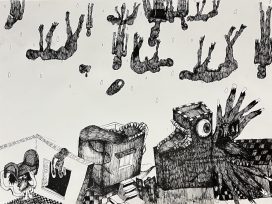

“The system” with its intrinsic power – is the final and fundamental realm, with its own set of rules, conventions, capital exchanges and closed circles. Is this modifiable in any way? Dan Perjovschi employs deep irony with his almost cartoonish charcoal drawings in “Site specific – Time specific”, while Josh On’s “The Rule” details the entrenched relationships of the power elite in an amazing yet terrifying database visualisation.

So, as Nori wisely points out: “In a society of consumption and ephemera, the value of a product must be constructed”. In this exhibition, multiple paradigms are constructed, illustrating the loose and amusing relationship between art and money.