Are the Russian people Putin’s victims or collaborators in crime?

Lacking a positive national identity, Russians continue to be governed by a dangerous imperial mindset that betrays both subservience and aggression. Putin has cynically built on this dubious foundation.

The cliché that the war against Ukraine is squarely on Putin’s conscience is still gaining traction in the international discourse. The people of Russia are said to be brainwashed victims of propaganda and censorship, suffering the effects of Western sanctions.

President Biden even said in March that ‘You, the Russian people, are not our enemy.’

Is this position tenable? I believe not.

The majority of Russians are criminally negligent. They are failing to meet minimum human standards of conduct, guilty of willful blindness to Putin’s atrocious war against civilians and urban centres. And many of them are actively participating in the destruction.

Unsettling figures

A poll released on 30 March by the Moscow Levada Center, an independent pollster, found that 83% of Russians presently support Putin’s actions, an increase from 69% in January. Days earlier, we saw thousands of Russians gathered in Luzhniki Stadium in Moscow for a pro-war rally that included Russian Olympians parading the nationalist ‘Z’ symbol.

Even if one takes the polls and rallies with a grain of salt, the stratospheric numbers leave little doubt that Putin and the Russian people are very much on the same page, with only a courageous but ineffectual minority dissenting. Let’s recall that a disturbing majority of Russian people were bursting with pride in 2014 when Putin annexed Crimea. He received 86% approval ratings in June of that year.

While excuses can be contrived for the Russian people – intellectual sloth, apathy, restricted sources of information – they remain objectively and practically not only opposed to the West, but active enablers of an unprovoked war of aggression, from which they derive a certain amount of national satisfaction.

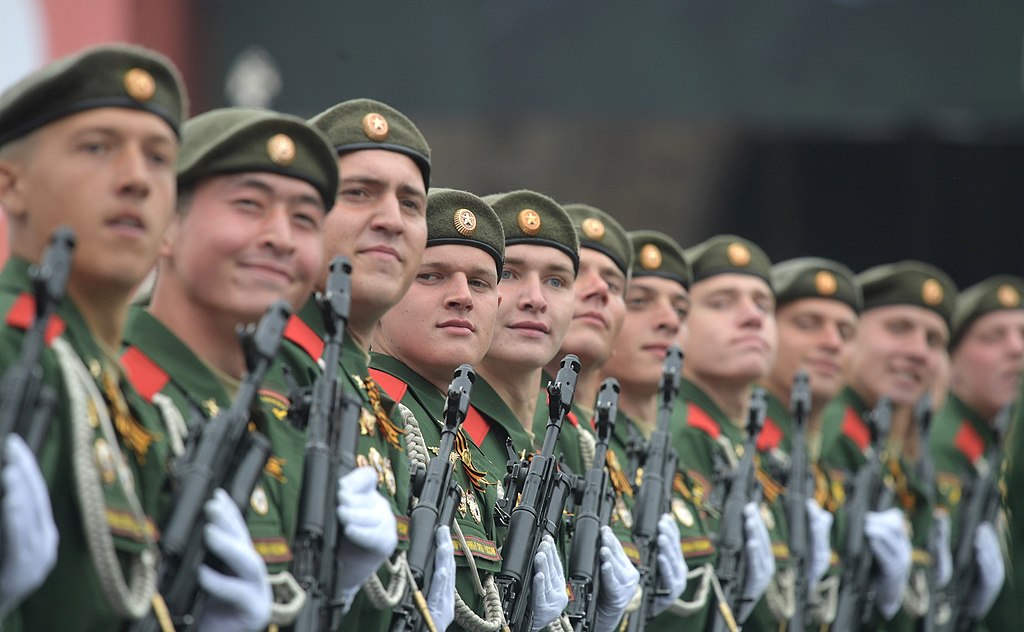

No shortage of machine guns at the 2019 Victory Day parade in Moscow. Official photo by the Kremlin via Wikimedia Commons.

On April 3, President Volodymyr Zelensky appealed to the morality of Russian mothers:

I want every mother of every Russian soldier to see the bodies of the killed people in Bucha, in Irpin, in Hostomel… Russian mothers! Even if you raised looters, how did they also become butchers? You couldn’t be unaware of what’s inside your children. You couldn’t overlook that they are deprived of everything human. No soul. No heart. They killed deliberately and with pleasure.

Surely, Putin would not have invaded Ukraine had only 15% of the population supported him. This is a war being waged by Russian society as a whole, including the Russian Orthodox Church. So it is worth considering Russia’s collective guilt (Kollektivschuld), just as it was warranted in the case of Nazi Germany.

A nation never built

The current war was not inevitable, but it did flow rather naturally from deep-rooted prejudices in Russian society. Historians have been pointing out for decades that Russians are still struggling to become a true nation. British historian Geoffrey Hosking wrote in 1998 that ‘for more than three centuries’ the ‘building of an empire’ ‘impeded the formation of a nation’.1

About two years ago Russian journalist and historian, Sergei Medvedev, observed:

There is a nation in Belarus, there is a nation in Ukraine – [but] there is no nation in Russia. There is [only] a type of people who are the property of the state, state serfs.

In the absence of a national identity, Russians continue to be governed by a dangerous imperial mindset that betrays both subservience and aggression. Putin has cynically built on these two dubious foundations. He has sidetracked Russians from the hard work of nation-building. He has refocused society’s attention on the alleged grandeur of the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union, saying bad Russian leaders and foreign enemies undermined them.

Russians, as a result, are wallowing in the stupor of a dying imperial identity, directing their ire especially at Ukrainians, who, because of their sovereignty, play a central role in Russia’s sense of ‘national’ loss. In fact, Ukrainians are seen as the greatest threat to the so-called ‘Russian identity’ and, for this reason, are met with Russia’s wrath.

This war was prepared for

During his reign, Putin has expressed his share of boneheaded ideas about Ukraine. None of them were original. The Russian mindset driving this war has been evolving for a long time. Moscow’s imperial control of its southwestern borders was always justified by the so-called ‘all-Russian’ concept, according to which Ukrainians and Belarusians must be part of the Russian polity and identity rather than separate east Slavic nations.

This effort can also be observed in cultural imperialism throughout the centuries. In 1843, liberal literary critic Vissarion Belinsky, a revered icon of Russian culture, wrote: ‘Ukraine was never a state, therefore, it had no history in the strict sense of the word’; ‘Ukrainians,’ he insisted, ‘have always been a tribe and have never been a nation, much less a state.’ He used these arguments to style the Ukrainian Nikolai Gogol as a Russian writer.

In 1863, Russian journalist Mikhail Katkov declared: ‘Ukraine has never had a distinctive history, has never been a separate state, the Ukrainian people is a wholly Russian people, a native Russian people, an essential part of the Russian people without which it cannot go on being what it is.’

Contemporary Russian historian Alexei Miller observed that the notion of Ukrainians ‘as a part of the Russian people was preserved as the official position of the authorities and as the conviction of the majority of educated Russians throughout the nineteenth century.’ This was ‘key to Russian nation-building in the imperial period’.2

Fast-forward to 2008, and we find Putin telling President George W. Bush: ‘You do understand, George, that Ukraine is not even a state. What is Ukraine? Part of its territories is Eastern Europe, but the greater part is a gift from us.’ In 2021 Putin authored an article ‘On the Historical Unity of Russians and Ukrainians,’ expressing his firm belief that ‘Russians and Ukrainians [are] a single whole.’ A recent study by the Royal Institute of International Affairs Chatham House flagged this myth as ‘justifying Russia’s current irredentist ambitions towards its western neighbours.’

And religious leaders are also on board. According to a report from 4 April 2022, Russian Orthodox Patriarch Kirill gave a sermon that refuses ‘to acknowledge the distinction between Russian and Ukrainian culture and identity, and it denies Ukraine’s right to exist as a sovereign nation, both historically and in the present. Furthermore, it legitimizes the ongoing violence as necessary and even, perhaps one could argue, holy.’

For centuries, Russia has been telling itself lies, and the war against Ukraine is clearly a way of satisfying old-time imperial longings. This also postpones society’s reckoning with the historical truth. A clear example of this effect was when RIA Novosti, the Russian state news agency celebrated victory over Ukraine a little prematurely, explaining two days into the invasion that ‘Russia is restoring its historical wholeness, gathering the Russian world, the Russian people together in all its totality of Great Russians, Belarusians and Ukrainians (malorossov).’

The horror of a better option

Russian society has a tendency to revive notions like this, and especially so in times of Ukrainian political ascendancy, as has been the case over the last thirty years. Ukraine’s success triggers a sense of imperial loss in its eastern neighbour, invoking a feeling that Ukrainians are keeping Russians from being ‘themselves.’ The extermination of Ukrainian independence is offered as an option to secure Russian imperial identity.

In theory, Russia could always choose alternate, democratic models of self-definition instead of the one Putin is reviving. Unfortunately, none of these alternatives have developed a prominent discourse among Russians so far. Whenever democratic elements appear in the imperial state, centrifugal forces within the state lead to their destruction.

The Russian Empire and the Soviet Union never found ways to incentivize non-Russians to accept the empire. Ukrainians and other nationalities developed competing and ultimately more attractive national narratives.

Putin seems to believe that the Russian Federation can be preserved solely through authoritarian rule and territorial expansion. There’s a reason why he doesn’t think of other ways: positive nation-building would require not only respect for democracy and civil liberties, but especially for the national differences that surround Russia. Russians would need to wean themselves off the daydream of restoring the old imperial borders. Imperial historiography would have to respect the national discourses of Ukraine and enter into a dialogue rather than try to erase them.

This, of course, is a tall order. Given Russia’s centuries-old delusions, intellectual arguments seem, for now, powerless to change imperialist behaviour.

The only present remedy for Russia’s sociopathic mindset would be Ukraine’s complete and total victory. Russia’s defeat in this war is the prerequisite shock therapy that might jolt Russians to accept that Ukraine is not – and never was – Russia, and perhaps even set the stage for a sustainable nation-building.

If Ukraine loses, Russian imperial fantasies will be reinforced; Russian society will redouble its search for imperial ‘wholeness’ – by turning toward the ‘lost’ territories that are currently found in the European Union.

Geoffrey Hosking, Russia: People and Empire, 1552-1917.

See: Alexei Miller, The Ukrainian Question 24, 26.

Published 9 May 2022

Original in English

First published by Eurozine

© Oleh S. Ilnitzkyj / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTIn collaboration with

In focal points

Newsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Related Articles

House keys recur in the stories of Crimean Tatars and Palestinians displaced from their respective homelands in the 1940s, and Ukrainian citizens fleeing Russian invasion since 2014. Ethnographic research and discourses on art and justice show how objects emblematic of home salvage the history of exiled peoples from oblivion.

Outrage and moral panic have become driving forces in global politics – but what role should emotions play in democratic governance? On the new episode of Standard Time, researchers examine the influence of moral emotions and their implications for political life.