Are crises necessary?

Debates on Europe: Budapest & Beyond

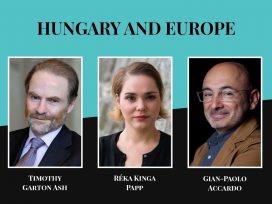

As a historian his expectations are gloomy, but as a political writer his optimism is strategic: Timothy Garton Ash talks about the European Union’s internal flaws and debates whether crises and collapses are always necessary for renewal.

Timothy Garton Ash: Since the Brexit vote, we have been facing a tragic dilemma. One rationale voiced by people like Emmanuel Macron is that it must be better for countries to remain inside the European Union than to leave. Consequently, they need Britain to do worse than the remaining member states. But as an English person, obviously, I can’t want my own country to do badly. Hence that formula: I want post-Brexit Britain to do well and the EU to do even better.

During the COVID crisis Brexiteers have been gloating about the slow rollout of vaccines in the EU and the impressively fast rollout of vaccines here. You can certainly see that kind of ongoing competition. More broadly, however, a lot depends on how Europe comes out of the crisis. If the European Recovery Fund really goes well; if the Union gets its act together as far as external policy is concerned; if the Green New Deal becomes a reality; and if the Union actually becomes an effective defender of democracy in its member states, then this could be a positive turning point.

Analytically, I’m quite sceptical about that. I’m fearful of the consequences, because the economic long-COVID will no doubt mean unemployment, insecurity, high public debt, and probably inflation. And those are great conditions for populists.

Gian-Paolo Accardo: How is it that the EU is so brilliant in defending its economic and trade interests – look at how it managed the Brexit negotiations, for example – and seemingly so weak when it comes to defending its core values of solidarity, the rule of law, or fundamental rights. Procedures like Article 7 of the Treaty of the European Union can, of course, suspend some rights of member states who violate such core values. However, it doesn’t seem to prevent authoritarian leaders like Viktor Orbán in Hungary from moving forward with their illiberal plans.

Timothy Garton Ash: I regard the crisis of democracy in Hungary in particular, but also in Poland and Slovenia, as major an existential challenge for the European Union.

Very few national constitutions speak as much about democracy, the rule of law and human rights in their first ten articles as the European Treaty does. In constitutional theory, this is a democratic union, which is a union of democracies. But as you rightly say, we now have a full member state, Hungary, which is no longer a democracy. It’s a hybrid regime, I would say, a competitive authoritarian state. It’s beyond illiberal democracy.

How is that possible? Historically, this current conglomerate is based on the European Economic Community. The Europe of values was conceived in and delegated to the Council of Europe, the Strasbourg Court of Human Rights, the OSCE. It was a tragic divorce of the two Europes all the way back to the original founding. Then we have tried to retrofit the values to the European Economic Community. We’ve been trying for 20 years, but Hungary shows that we haven’t yet made the effective linkage between the Europe of values and the Europe of money.

Réka Kinga Papp: Let’s talk about where this democratic procedure stumbled, and how it is being demolished. As an occupational hazard, I’m specifically interested in media freedom, with independent media in Hungary actually in danger of extinction. Do you think it results from the history of the region? Especially when compared with very different political developments in the neighbourhood, in Slovakia, Romania and even Ukraine.

Timothy Garton Ash: When the Berlin Wall came down and the Velvet Revolutions started, we had the extraordinary opportunity of moving towards a Europe whole and free. This is a central experience in my life, as it is for many others.

The European community said, let’s translate democracy into a set of criteria for membership, the Copenhagen Criteria. Hungary was, in fact, the first of the new democracies to apply for EU membership. For Viktor Orbán, the whole experiment has been about member state building. All democratic institutions and laws and regulations were built to qualify for becoming a member state of the European Union.

As it turns out, the criteria are very rigorous up to and until the moment you join, but as soon as you’ve joined, you can do more or less whatever you want. There are absolutely no mechanisms to discipline member states effectively. What is more, you can dismantle democracy while keeping the facade of a perfect liberal, pluralist member state.

To use the analogy of a Potemkin village, I would say Hungary is a kind of Potemkin city. That’s to say every feature of the facade is beautifully preserved: media freedom, pluralism, on paper it looks relatively fine, because well-trained officials and lawyers educated at good European universities know exactly how to play the European game. Importantly, Orbán can always point to one of the other democracies in Europe and show an analogous example for the offense he’s committing. The media regulation doesn’t look too bad on paper, for example, but the reality behind the Potemkin facade is completely different. Control is asserted not through censorship – that’s so old fashioned! It’s control through ownership, through tax, through fiscal review, through entirely informal instruments, with the involvement of friendly oligarchs and so on. To tackle this it would take real political will from the side of the European Union.

At the moment, we have a really dishonest game. In the bad old days of the Soviet bloc, the joke said: ‘we pretend to work and they pretend to pay us’. Now the very dishonest game between Viktor Orbán and Brussels is this: ‘we, in Hungary, pretend to be a democracy and you pretend to believe us’.

Réka Kinga Papp: And you also pay us! …

Timothy Garton Ash: … And pay! Billions of euros, which the national government can distribute as it sees fit. For example, to reward friendly media-owning oligarchs, not to mention friends and family.

But the key here is the lack of political will on the side of the EU, the unwillingness to look behind the facade. Why is that lacking? Well, first of all, because the EU has no shortage of other crises: refugee crisis, Eurozone crisis, Trump crisis and… now the COVID crisis. On the other hand, there is a long history going all the way back to the Enlightenment, of west Europeans looking down their noses at east Europeans and regarding them as not really properly a part of Enlightenment Europe, but somehow tendentially always autocratic or authoritarian. There’s a great book by Larry Wolff called The Invention of Eastern Europe, which traces that attitude all the way back to the Enlightenment. What I hear in many statements by west European leaders, notably French and Belgian, but also others, is that old prejudice: ‘Well, eastern Europe was never really Europe anyway’.

The current situation results from a combination of the Potemkin city game – the fact that there’s so much else going on a limited bandwidth – and those old prejudices, which often make me and others feel that we’re fighting a rather lonely struggle in trying and make European leaders actually recognize that this matters.

Réka Kinga Papp: But does this narrative explain what is happening right now in Slovakia, for example, a country where there is a strong anti-corruption turn in popular politics? Or in Ukraine? And we’ve seen a very strong protest wave in Romania, too. There is a strong regional pattern of promising democracies turning down an authoritarian path, but also certain other countries seeing large popular movements and a strong push for anti-corruption policies and democratic renewal. Is it an accidental allocation of democratic enthusiasm?

Timothy Garton Ash: The phenomenon could be described as intra-European orientalism, the othering of eastern Europe. And the first thing to say is: eastern Europe doesn’t exist. These are incredibly diverse countries which have some features in common. One of them being that they’re all post-communist countries. That post-communist trajectory, of course, explains a lot of the corruption. The privatisation of the nomenklatura, the weakness or even neglect of the rule of law. But in analysing these historical trajectories, you find a pushback against these tendencies in certain countries. Action and reaction.

Often precisely where the post-Soviet methods have been worse, as in Slovakia and Ukraine, you find the reaction, the pushback against that phenomenon. In Poland, you now find what Jürgen Habermas famously called ‘constitutional patriotism’. It’s precisely because the attacks of Law and Justice, PiS have targeted the Constitution, that Polish patriotism is now focused on the Constitution and the courts. I heard that at recent demonstration in Krakow people were chanting as a slogan ‘Trójpodział władzy!’, which means ‘triple separation of powers’. There aren’t many places in the world were people take to the streets chanting ‘triple separation of powers’, are there?

I think that’s how we should examine this bifurcation: it’s about individual national powers, their actions and reactions.

Gian-Paolo Accardo: You mentioned the erosion of some fundamental liberties, especially in Hungary. What is the receipt for establishing an illiberal regime at the heart of the EU? Is it the Hungarian salami tactics, cutting off basic freedoms one slice at the time, so that the public doesn’t realize that the salami is getting smaller and smaller until it’s gone? Is there a tipping moment when one can say that a country is not a full democracy anymore?

Timothy Garton Ash: Hungary is no longer a democracy; that is the formulation I would choose. Illiberal democracy – even though it’s a contradiction in terms, like fried snowballs – is, in fact, a useful term to describe a period of decay, of dangerous decay, of a liberal democracy. Poland, I think, is an illiberal democracy. Hungary, however, is beyond that point. Hungary has kept the facade of the Potemkin city, it looked like a perfect member state in 2010; the political scientist Alfred Stepan at the time actually said that Hungary was a consolidated democracy. But then, building by building, democracy was demolished behind the facade, accompanied by excuses for every move:: ‘Oh, but, you know, they do that with the Supreme Court in Belgium’ or ‘Oh, but they do that with media regulation in Austria’. And gradually, to use the old Marxist vocabulary, quantity becomes quality, an what you have ended up with is essentially an oligarchic or authoritarian control legitimated by elections – hence the term ‘competitive’ authoritarian.

The EU provides billions of euros going into structural funds and now into recovery funds to countries like Hungary and Poland, which are then distributed by the national governments, often used for purposes of political patronage or political rewards. This results in very high levels of corruption, as established by the EU’s corruption monitoring authority, which at one point found that close to 50 percent of public contracts in Hungary had some element of EU money and some element of corruption about them.

The tragic thing is that the EU, which served as a major facilitator of democratic consolidation in the first fifteen years after 1989, has not merely not prevented the erosion of democracy in the next fifteen years, it has actually facilitated this erosion.

Gian-Paolo Accardo: What responsibility do the US and other specific western countries have for this situation?

Timothy Garton Ash: First of all, Orbán and Kaczyński and others have lost their great mate in the White House, Donald Trump. And instead, you have a liberal democratic administration. I think that the Biden administration, with its democracy and human rights agenda, will have a very positive impact. This is going to be crucial for the defence of free media in Poland, where American companies own some of the key private media, such as the television channel TVN. Free media is now the frontline of the struggle for democracy, particularly in Poland. In limited areas, I think the US is going to be very important, but it’s nothing compared to the responsibility of the EU and of countries within the EU.

Let’s be clear about this: the central power in Europe is now Germany, particularly in relation to eastern and central Europe. I heard a Polish economist once describe the Polish economy as part of the German economy. I’m sure a Hungarian or a Slovak economist could say something similar. And the lack of political will from Berlin to push the expulsion of Fidesz from the EPP has been, in my view, a major reason behind the failure of the EU so far.

Therefore I have hopes for the next German government, because at the moment the Greens are ahead of the CDU-CSU in Germany, and if it stays like that they will probably be a major part of the new coalition government. The Greens are by far the most pro-European, pro-liberal, pro-democratic party in German politics.

Réka Kinga Papp: Eastern to central European EU members can be conceptualised as peripheral markets to the rest of the EU. And the wage vacuum is so pervasive that it basically permeates everything, both through immigration, through international commissions – and this is also the lifeline for many who do stay in these countries. But some people don’t. There’s a debilitating shortage, for instance, in health care professionals and care professionals altogether, and in a whole range of other essential professions.

Timothy Garton Ash: They are here in Britain, or in Paris, or Berlin.

Réka Kinga Papp: Do you think that this demographic push and pull is going to be a factor, at any point, in a political change?

Timothy Garton Ash: Obviously, Viktor Orbán is trying to detach the very notion of the European Union from the regime type of liberal democracy and to say: we represent a different Europe, a better Europe, more national, more Christian, with more traditional values. Here many similarities can be found with Putin’s ideological agenda. This is the ideological framework of the challenge we’re facing. It’s very hard to think of a time in modern history where Hungary has actually been more important in the larger European context. It’s an amazing achievement in a way to become the spokesman for that other Europe.

Nonetheless, entire societies have gone through tremendous modernisation and Europeanisation. I think that political reaction is being challenged by social action, and this mechanism is kicking in strongly in all these societies. If we can keep the political framework and the values framework of the European Union intact, I think longer term social and cultural processes will play through in a positive way also in Hungary, because even if it’s not a democracy, that doesn’t mean that you can’t win elections.

Gian-Paolo Accardo: The main political development of the recent years is the normalisation or, as you would say in French, the banalisation of the far right discourse in mainstream politics, leaving even centre or moderate political parties shifting toward far-right ideas. How can the EU stand for its core values when the far right and the most nationalistic views are becoming mainstream?

Timothy Garton Ash: First of all, the EU has to start practising what it preaches, or it will lose its credibility. I don’t think that just because you have a right-wing government here or there you’re prevented from doing this. However, if the whole centre, including western-European countries, moves too far to the nationalist right, then we’re in trouble. I’m wary of using the word fascism, because it has been so devalued by hysterical use by the Left, to denote everyting from an authoritarian schoolteacher to Adolf Hitler, but nonetheless there are elements from the fascist mix which have crept back into politics, also in western Europe. But that fight has to be fought in the individual countries. Let’s face it, currently Marine Le Pen is neck and neck with Emmanuel Macron. That election is going to be incredibly important.

But if, as I hope and believe, we in western, northern and southern Europe manage to move back towards liberal European values and practises, then this will in turn become a powerful force in centaral and eastern Europe. It will get much more difficult to sustain the Orbán-Kaczyński model if the rest of Europe is not, as in the last six or seven years, moving their way, but back the other way.

Réka Kinga Papp: I do wonder whether it actually takes a huge breakdown every time for a democratic renewal, whether the EU needs a dysfunction of such magnitude to reform its ways. Isn’t there any other way? Is there any way to avert a deep existential crisis, or is catastrophe a necessary prerequisite for change?

Timothy Garton Ash: You can write the whole history of Europe as a story of not learning from history, going through one disaster after the other, one war after the other, saying ‘never again’, only to have it happen again in Bosnia, in Ukraine, and so on.

So can we prove Heraclitus wrong when he said war is the father of all things? Can we learn the lessons without going through the crisis? It’s not as if we haven’t had a few crises in the last decade. The question is: has it had a sufficiently galvanising effect? That is the question of questions. As a historian, I have to be pessimistic. I fear that old Heraclitus may yet again prove right and we have to go even further down before we see the recovery. But as a political writer, I’m doing everything I can. I’m currently working with a group of young Europeans here in Oxford to see if we can actually learn from history without having to go through it again.

Réka Kinga Papp: That’s both a painful and hopeful place to be.

Timothy Garton Ash: The famous formula is: pessimism of the intellect, optimism of the will. It always helps to take a fairly dim view of the probabilities. This is something, by the way, where I think Hungarians are very good, because they are world masters of pessimism.

Réka Kinga Papp: Oh yes! We excel in pessimism.

Timothy Garton Ash: Absolutely, but this can be an asset intellectually. In the 1970s, people in the West thought the Soviet Union was going to catch up with and overtake the United States. They thought our democracies were in a complete mess after Watergate and Vietnam. They thought the US’s authority was utterly destroyed. And out of that intellectual pessimism, we generated the reforming energy for one of the most dynamic and hopeful periods in European history, the 1980s and 1990s. Then in the 2000s we did the opposite. We became fantastically complacent and pleased with ourselves. Mission accomplished, we said, democracy seemed consolidated in Hungary and Poland, democracy was being brought to the Middle East, hooray for the Arab Spring and so on. Capitalism was all going wonderfully. And hey presto, look what happened next: the financial crisis.

That is why I think intellectual pessimism is quite a good starting point for political activism and in the end, for political optimism.

Published 4 May 2021

Original in English

First published by Eurozine

© Debates on Europe / Timothy Garton Ash / Réka Kinga Papp / Gian-Paolo Accardo

PDF/PRINTNewsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Related Articles

Voicing opinions to explain political tensions from afar is contentious for those treated as mute subjects. Focusing solely on distant, global decision-making disguises local complexity. Acknowledging the perspectives of East Europeans on Russian aggression and NATO membership helps liberate the oppressed and open up the debate.

Arbitrary lines

The idea of Europe – and its consequences

The myth of European exceptionalism no longer holds: the continent’s boundaries are arbitrary, its heritage mixed and controversial, and unfit for a unified identity to hold it together. If we give up the commonplaces that have proven insufficient, what can then define and unify this peninsula of peninsulas? True democratic dissent, Ferenc Laczó argues.