Another lost generation of art?

Artist Marharyta Polovinko’s creativity persisted in a tormented form through her experiences as a soldier on the Ukrainian frontline. The words of a recently called-up fellow creative and young family man provide a stark reminder that the Ukrainian military is buying Europeans time.

War tells many stories, and this is one of them. On 5 April 2025, artist and soldier Marharyta Polovinko was killed while serving on the frontline of Russia’s full-scale war against Ukraine. She was 31 years old. Her death is one of hundreds of thousands on Russia’s hands. And yet it is a blow that feels both devastatingly personal and tragically symbolic for the Ukrainian cultural community, where I have been active for the past decade as a contemporary art curator.

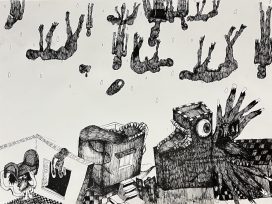

Sleeping in the Trenches, 2024, Marharyta Polovinko. Image courtesy of the artist

I did not know Marharyta well. We saw each other from time to time at openings, where we might share a friendly word, and followed each other on social media. Yet her death struck with the intimacy of a mirror shattering. Mourning her, I learned we were born on the same day in 1994.

There is a terrifying closeness in this coincidence. I received news of her death while serving in the Ukrainian army myself, having been called up a month earlier. Being mobilized provokes complex feelings. I’m a 31‑year‑old male citizen of a country at war. I am a native of Luhansk, a city in Ukraine’s east that has been occupied by Russia since 2014. My family fled when Russian troops took control of the city. At that time, I was studying in Kyiv and have never had the chance to return home since. After three years of full-scale war, I have always been morally ready to join the army. Yet I didn’t volunteer for military service. My wife and I have been raising our small child together. Supporting her career, I’ve often taken on the role of primary caregiver. However, the state decided it needed me to serve, and I accept that decision – though it pains me to be away from my family. I hope to repay my debt to people like Marharyta who bought us time.

This is blood, this is pain, this is suffering

Before the war, Marharyta Polovinko painted her native Kryvyi Rih and the fragile figures of post-industrial society. A graduate of the National Academy of Fine Arts and Architecture in Kyiv, she created thoughtful, often raw portraits of life on the peripheries. Her 2019 painting Three Graces of Urbanization, made from gouache, charcoal, stones and paper, captured not an idealized muse but the burdened beauty of life among slag heaps, psychiatric clinics and collapsing concrete. In one of her most haunting pieces Kryvyi Rih Residents Near the Night Shelter, she revealed not only the aesthetic of the margins but also their dignity.

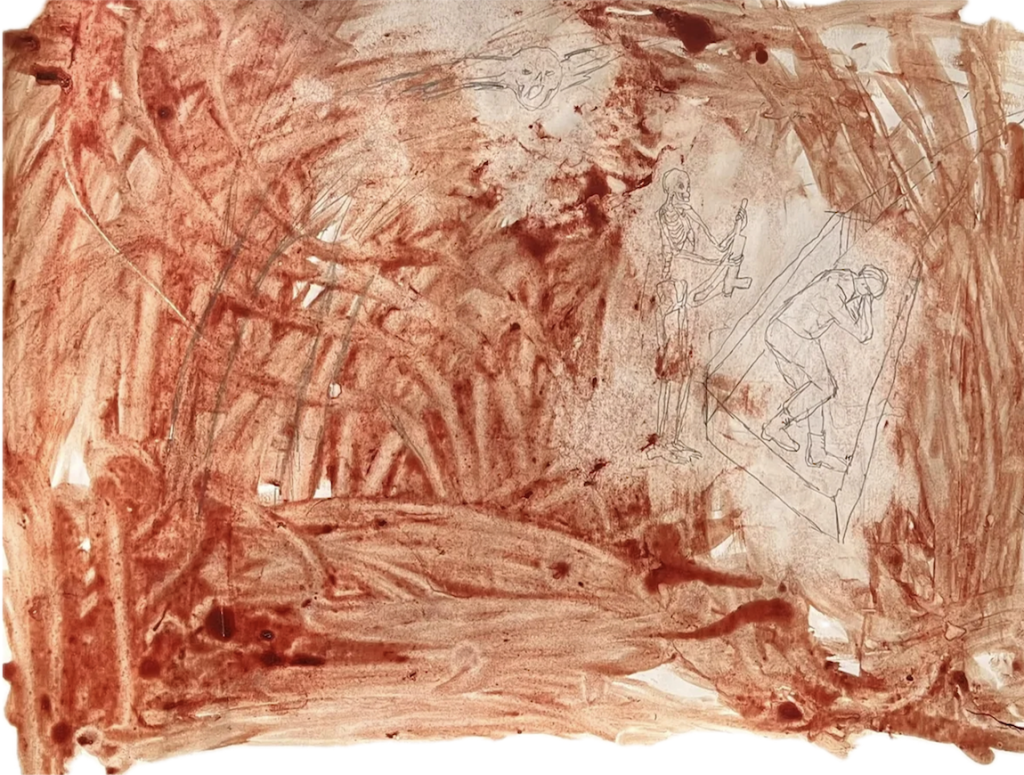

Like the work of other Ukrainian artists, Polovinko’s art mutated in 2022. She began to draw compulsively. Her materials became symbolic: drawings made with pens drained of ink, even with blood, to convey the raw and unfiltered pain of her generation. ‘Art came to me where it was most unbearable without it,’ she said in a 2023 interview. But she also admitted that her war drawings felt unshareable: ‘This is blood, this is pain, this is suffering. It’s a material that has no place. I don’t want it to exist.’

Still, she kept drawing – even as she volunteered to evacuate wounded soldiers in frontline medical vehicles. She drew during breaks between missions in Mykolaiv and Kherson. Her work started to reflect not just the collective horror of the news but also deeply personal memories, portraits of comrades, of death, of survival.

By the time she died, Polovinko had joined the Ukrainian army as a soldier. Her comrades remember her as courageous, honest and steadfast – a person who ‘did more than what was asked’. She was killed during a combat mission with a weapon in her hands – with dignity. She was buried on 11 April in her hometown, Kryvyi Rih, on the Alley of Glory.

Marharyta Polovinko, soldier of the 2nd Mechanized Battalion of the 3rd Separate Assault Brigade. Image via Instagram

A generation on the edge

In an earlier essay about the possibility of returning to my native Luhansk, I wrote: ‘Violence in Ukraine is an all-encompassing logic brought to our country by Russia. Before we talk about rebuilding, we must understand that the return will be led by soldiers, by partisans, by those who first reclaim the land.’ That statement was made from a position of theoretical distance. Today, I rewrite it from within this logic itself – and from within the grief that it produces.

Even before I was mobilized, I sensed a new feeling among my generation. We were raised in the 1990s with the belief that freedom had already been won. But over the past decade, as we entered adulthood, we were forced to learn what it means to fight for dignity. Today, as our cities burn and our loved ones fall, we see that the struggle is far from over. With that realization comes not only grief but also a deep, generational sorrow. A sorrow that comes from watching your peers fall – not in an accident or to disease but from missiles and bullets.

My generation of cultural workers is being remade by loss. Like those who resisted Soviet oppression and paid with their lives for writing in the Ukrainian language or carrying the national idea, we are learning to inscribe our defiance and will into history. This war is forging us – its rough suffering, which in itself is leaving an indelible mark, is being transformed into an urgency to speak and remember.

Through this war, cultural production in Ukraine continues as a testament to the enduring value of art in the face of destruction. Ukrainian artists, writers and thinkers continue their work, even as the war renders their practices increasingly precarious. We are learning how to remember, how to resist, and how to speak in a language that carries both the weight of the past and the urgency of now.

In this context the exhibition Regarding the Ants’ Burrow Before the Rain, which I recently co-curated with my wife Oleksandra Pogrebnyak at thesteinstudio in Kyiv, tells stories of the fragile possibility of preserving oneself amidst profound historical shifts. It explores the entangled relationship between modernization and the experience of displacement, revealing how grand infrastructural and geopolitical projects not only reshape landscapes but also destabilize one’s sense of agency and subjectivity.

We began the opening with a minute’s silence. I wrote my opening note while in the training camp and Oleksandra read it to the audience on my behalf.

When moral clarity matters

Polovinko’s death is more than a private tragedy. It is an indictment. It is a mirror held up to a Western world that has grown used to looking away. A world where geopolitical complexity too often overshadows moral clarity. For Ukrainians, it is not optional. Moral clarity is lived. It is buried in the cemeteries of Kryvyi Rih, painted in blood and blue ink on the frontline.

Don’t look away from Marharyta’s smiling face. Her death should not be a footnote. Nor should she become just another name in a war archive or a ‘fallen talent’ in some future exhibition on another lost generation of Ukrainian art. We are not a lost generation yet. But we are at risk. Honour Marharyta. Honour Ukraine.

Published 24 April 2025

Original in English

First published by Eurozine

Contributed by Institute for Human Sciences (IWM) © Dmytro Chepurnyi / Institute for Human Sciences (IWM) / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTIn collaboration with

In focal points

Newsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Related Articles

Under the aegis of the Council of Europe, a ‘core’ group of countries have been moving forward with plans for a tribunal capable of prosecuting the Russian leadership for the crime of international aggression. The US administration’s switch of allegiance now puts these plans at risk, writes Gwara Media.

The fall of the Berlin Wall, and not the human chain across the Baltics, is emblematic of 1989. But what if this show of unity had become iconic of communism’s disintegration? Could acknowledging Eastern Europe’s liberation positively reframe what Russia otherwise perceives as loss since the Soviet Union’s demise?