Soundings is a British journal of culture and politics founded in 1995. Its main focus is on the second of the three roles identified in Eurozine’s 2018 study of European cultural journals – the facilitating of debate and discussion. And it also corresponds to the idea of a ‘little magazine’ referred to by other contributors to Eurozine’s focal point ‘Worlds of Cultural Journals’: Soundings is a journal that concerns itself with a particular set of questions, and sees itself as a project, a conversation with others interested in the same central questions. The strongest influence on Soundings is the New Left tradition. Broadly speaking, the journal aims to develop in-depth analyses of the complex forces that are at play in contemporary political and cultural life, in order to assist in the creation of a serious challenge to currently dominant ideas and forces. This article traces some of the sources and trajectories of the particular strands of New Left thinking from which Soundings has emerged, and briefly considers their relationship to contemporary thought.

For a number of different reasons, the period when the first New Left emerged in Britain – the late 1950s – coincided with a time when the question of the relationship of culture to society and politics was becoming a central part of the intellectual agenda. Within the first New Left, this question was always connected to an effort to understand specific political formations and the way they were changing, the nature of the popular, and the question of agency; and alongside this there was a recognition that the sphere of politics had to be expanded to include the cultural.

This recognition of culture as an integral part of politics has remained an abiding concern within the New Left tradition and continues to inform Soundings’s own editorial group. In the light of Eurozine’s ongoing discussions on exactly how to define cultural journals, this article therefore pays particular attention to this theme.

Soundings 38 (2008)

The meaning of culture

Tom Steele argues that the first New Left’s engagement with culture should be seen in the context of the wider democratisation of culture that took place in western Europe after the Second World War. Alongside the expansion of the welfare state and increasing access to education, culture itself was being transformed, as ordinary people moved to a more central position in the public arena; people were becoming more confident, less willing to be confined to a subordinate position. This fed into ongoing intellectual efforts to define what culture actually was – and also contributed to a gradual change in the meaning given to the word culture itself.

One of the spheres in which these debates about the nature of culture had been developing was in adult education – a sector whose raison d’être was to widen educational opportunities and access to culture. Steele documents the debates in the Workers’ Education Association (WEA) in the 1940s between George Thompson, the director of the Yorkshire WEA, and W.E. Williams, the editor of the WEA journal Highway, which exemplify the points at issue. Williams still viewed culture as ‘something akin to the Arts and the cultivation of sensibilities in the light of the best creations of society’. The role of the WEA was to widen access to this culture. Thompson, on the other hand, saw the cultural creativity of the working class in its collective organisations – which he viewed as a much greater achievement than anything the middle class had managed. In 1940 he wrote:

By culture I do not mean the snobbish notion of intellectual polish with which a section of the nineteenth century industrial and commercial middle class coated itself as a defence against the charge of vulgarity made by ‘high society’ … I mean the older concept of culture as that quality of mind and understanding which comes through the effort to extend and improve the range of knowledge and by undergoing mental and moral discipline.

At this point the dominant meaning of ‘culture’ was still based on Matthew Arnold’s notion of ‘the best that has been thought and said’, but this definition was gradually being challenged by notions of an alternative, working-class culture – capable of challenging the old notions of high culture from which it had been excluded, and possessing its own culture of equal value. Many of these first New Left theorisers of culture, cultural politics and popular and working-class culture – Raymond Williams, Edward Thompson, Richard Hoggart – had themselves worked in adult education. Each in their own way now sought to understand popular culture and its relationship with politics.

In The Long Revolution, published in 1961, Raymond Williams (who had already published Culture and Society in 1958) describes the emergence of democratic culture alongside, and as a central part of, democratic life. Edward Thompson, in the Making of the English Working Class, published in 1964, sees working-class self-organisation and culture as central to the development of the labour movement – and the book itself, in its documenting of a usually disregarded culture, made a major contribution to the democratisation of notions of culture. Richard Hoggart, in Uses of Literacy, reflects on the working-class culture he himself grew up within; the ways in which that culture was being eroded by what he saw as ‘mass culture’; and the ways in which his own access to higher education had taken him away from this culture. All these seminal texts can be seen as part of this shift towards understanding the more complex ways in which culture, politics and class were linked.

Alongside this, the idea of popular culture – including the idea that there could be such a thing – was also developing. The term ‘popular culture’ first came to be widely used in the post-war period, partly as a way of understanding the new wave of working-class writers and actors; the expansion of sales of cheap but quality-content paperback editions by publishers such as Penguin; the growth of television ownership; and the emergence of new youth cultures in popular music and fashion. Moreover, this was also the time of the first wave of large-scale Commonwealth migration to Britain, which from the beginning had its effects on popular culture (and which also over time produced new ways of thinking about culture, both in terms of the ‘Black Atlantic’ and ideas about diaspora, and in terms of a reassertion of very conservative definitions of the English way of life). Popular culture was embraced by some but viewed with suspicion by others (including Hoggart), who saw much popular culture as being mere ‘mass’ culture, influenced by US commercial culture, and as having little value.

1956, the New Reasoner and Universities and Left Review

The events of 1956 – the invasion by Britain and France of Suez, the invasion by the USSR of Hungary, and the revelations about Stalinism at the 20th Congress of the Soviet Communist Party – were a major catalyst in the formation of the New Left. Stuart Hall, a leading thinker in the British New Left, described 1956 as ‘a conjuncture (not just a year)’. The political context sharpened a sense of the need to understand the constellation of forces that were transforming the world.

As Hall wrote, these events ‘unmasked the underlying violence and aggression latent in the two systems which dominated political life at that time’:

They defined for people of my generation the boundaries and limits of the tolerable in politics. Socialists after ‘Hungary’, it seemed to us, must carry in their hearts the sense of tragedy which the degeneration of the Russian revolution into Stalinism represents for the left in the twentieth century.

In Britain as elsewhere, many people left the Communist Party, and among those that remained there were painful debates on how to respond. Two of the leading lights in these debates, Edward Thompson and John Saville, set up a dissident journal to discuss the implications of what had happened, The Reasoner. After this debate became impossible inside the party, they left, in 1957, and started up The New Reasoner, with the aim of finding new ways of continuing the left tradition, and with an emphasis on culture and internationalism. The plan was to publish theoretical debate; documents and commentary; and ‘a wide range of creative writing – short stories, polemic, satire, reportage, poetry, and occasional historical or critical articles’. These would contribute to ‘the re-discovery of our traditions, the affirmation of socialist values, and the undogmatic perception of social reality’. Among other topics, the first issue included a defence of the Mau Mau in Kenya, a long piece by Edward Thompson on socialist humanism, a short story by Hungarian writer Tibor Dery, an article on Polish theatre, a substantial selection of poetry (a tradition Soundings still continues), and a translation of Sartre on the future of the French left. Hall called this strand of what became the first New Left ‘communist humanism’.

Another New Left journal, the Universities and Left Review was also set up in 1957, edited by four Oxford university students, among them Hall – spurred on by the events of ’56 but also born from an ongoing independent left intellectual project to find a third way beyond social democracy and communism. In these efforts, the editors and their colleagues knew they also needed to find a better theoretical toolset with which to understand contemporary capitalism than anything that was on offer from existing traditions of thought. One of the aims of ULR was to revivify socialist theory and intellectual analysis, which it saw as being severely impoverished in both the communist and social-democratic traditions. Hall later recalled the difficulties the group had in finding resources to discuss some of the issues they were trying to understand:

Whether we knew it or not, we were struggling with a difficult act of description, trying to find a language in which to map an emergent ‘new world’ and its cultural transformations, which defied analysis within the conventional terms of the left while at the same time deeply undermining them.

This journal, too, had an explicit focus on the arts. The editors noted in the first issue that the journal had expanded ‘outrageously’. It looked like becoming, ‘in miniature’, ‘a journal of socialist theory; a journal of left arts criticism; a journal of university opinion; a journal for left-wingers of the post-war generations; a medium for international socialist exchange’. A series of articles on ‘commitment in criticism’ was commissioned, contributors to which included the filmmaker Lindsay Anderson, the art critic John Berger and the poet Christopher Logue, and there was substantial coverage of the arts, and of culture more widely.

The two journals amalgamated in 1960, to become the New Left Review. What united the editors of this new journal was a recognition that times had changed – and that therefore so must the left – and a preoccupation with trying to understand the contours of the new forms of capitalism that were emerging. The New Reasoners were in the main from an earlier political generation, coming into politics before the Second World War and deeply influenced by the popular front policies of the 1930s; they were more traditional in their views on culture. The ULR people were younger, and had a stronger interest in understanding developments within post-war capitalism – the time in which their own political identities had been formed. All of the group were interested in issues such as the rise of the affluent worker, consumerism and mass culture, which they believed could only be understood by thinking about culture – and, more latterly, subculture. And all of them were interested in the effects this was having on working-class and left organisation. As Hall wrote, these debates were an important source of the New Left’s investment in culture:

First, because it was in the cultural and ideological domain that social change appeared to be making itself most dramatically visible. Second, because the cultural dimension seemed to us not a secondary, but a constitutive dimension of society.

There was a wave of new left activity connected to the journal: New Left clubs were set up across the country, and these became hives of activity, including cultural events and discussions as well as close engagement with CND – which was seen as a social movement of a new kind.

Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND) Rally 1962. Wikimedia

But these activities had peaked by the mid-1960s; and in 1962, after Perry Anderson had taken over from Stuart Hall as editor, New Left Review began to shift away from a more engaged involvement with the politics of the left in Britain – and what Hall calls the politics of agency – towards a broader intellectual engagement with developments within European Marxism and critical philosophy. These were, of course, also an important part of the New Left tradition, particularly in their contributions to the left debates of the 1970s and 1980s, but they represented a different strand from the one forged in the early days of the journal, and the one later picked up by Soundings.

One result of this growing interest in culture was the setting up of the Birmingham Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies (CCCS) in 1964. Richard Hoggart, its founder, was also its first professor. The establishment of the Centre is often seen as the foundational moment of the discipline of Cultural Studies – sometimes known as ‘British Cultural Studies’. As Hall later noted, the centre gave the new field of thought a necessary institutional base. Hoggart’s view of the culture and society debate was, relatively speaking, fairly traditional. But when Hall took over as director in 1968, the Centre became more preoccupied with theoretical debates, especially about the place of culture within a total social formation. This meant that the CCCS played an important role in the New Left debates of the 1970s and 1980s.

The 1970s and 1980s

The development of a New Left was a global phenomenon, and its growth was reflected in renewed efforts to try to find the necessary critical tools for understanding the changing world. At this point in time the left appeared to be in the ascendant. The spirit of ’68 and the growth of new social movements, the courage and imagination of the civil rights movement in the USA, the success of liberation movements in the global South and the defeat of the US in Vietnam – these all appeared as signs of the possibility of making a new world. This was the context for a period of creative rethinking within Marxism, and attempts to free Marx’s work from the straitjacket of orthodoxy. The New Left Review under Perry Anderson’s editorship played a crucial role in these debates in the UK, as did the publishing house it set up 1970, New Left Books (now Verso). But there were also contributions from the emerging Eurocommunist milieu, as a new generation of activists came through needing better answers for understanding what was happening than were then on offer from the traditional texts of communism.

One of the key theoretical questions that occupied people was the complexity of the relationships that existed within a social formation, and how they intersected. How could you look at society as a totality without over-emphasising the world of production – as had been the case with most communist and social-democratic thinkers of the previous generations? People wanted to better understand the relationship of the economy to ideology. It was clear that cultural battles were a central part of the new movements, and yet in orthodox Marxist thinking culture was seen as part of the ‘superstructure’, while the economy was the ‘base’; and it was the base which determined what happened in the superstructure. This was felt to be an insufficient approach to the role of culture in politics and society.

Stuart Hall noted on a number of occasions the scarcity of resources that existed for left intellectuals in Britain in the 1950s. This was one of the reasons they were so focused on literature and literary theory: there was not much else available in English in terms of writings on culture and society. The majority of the most widely available translations of Marx were little pamphlets seen as guides to action or to understanding the economy. Writers such as Lukács, Benjamin and Adorno and other European philosophers were in the main untranslated into English. Given the massive changes taking place in the world, and the rise of a new generation of activists, there was a need for ideas, and this included new ways of thinking about culture. The best description of how these debates informed the Cultural Studies mindset is to be found in Cultural Studies 1983, published in 2016 but based on lectures given by Hall in 1983. It is important to note that these debates did not take place in an ivory tower: they were seen as pressing questions for those who wanted to transform the world.

In the early years of the CCCS there was a strong focus on engaging with Marx, but rethinking the way his ideas on the social formation as a totality had been articulated. The work of Louis Althusser, himself influenced by Antonio Gramsci, was central to this rethinking. This process of working out can be seen in two of the centre’s most important publications, Policing the Crisis: ‘Mugging’, the State and Law and Order (1978) and The Empire Strikes Back (1982). Both books were multi-authored and based on a long period of discussion and the production of interim papers. You can see in the texts the way the writers are grappling with the issues and beginning to tease out new ideas – including the effort to analyse culture’s role as a determining force. This was a dialogue with an inheritance.

In Policing the Crisis, an investigation into how the word ‘mugging’ had become dominant in media accounts of crime, led on to a consideration of the wider issues of law and order, and then on again to an analysis of the emergence of ‘authoritarian populism’ – a way of describing the politics of Thatcherism. Returning to Policing the Crisis from the perspective of the twenty-first century allows one to see how these ideas were emerging alongside a notion that later became solidified in the idea of ‘conjuncture’, and the realisation that in Thatcherism we were seeing the replacement of one hegemonic formation (the social-democratic consensus) by another (Thatcherism was later recognised as an early form of neoliberalism). These ideas – all of which were informed by a more complex understanding of the relationship between politics and culture – were heavily influenced by Gramsci, a thinker whose writings first became widely accessible in English in 1971 with the publication of a substantial selection of writings from his prison notebooks.

Gramsci’s work became central to later iterations of the New Left. In The Empire Strikes Back, a group of black graduate students explored more fully how these and other ideas opened the way for new understandings of race. Gramsci’s idea of common sense was important here – the idea that what is regarded as an obvious, taken-for-granted mode of thinking is in fact an area of crucial political contestation: it stitches together different, often contradictory elements, to sustain a mindset that goes with the grain of and helps to secure the rule of the dominant groups in society.

One of the ways in which Hall thought about this was through the idea of articulation. The elements that were stitched together had no necessary, pre-given correspondence. This was an important part of the shift away from economic reductionism. But this idea of non-correspondence, alongside a deeper understanding of how subjectivities were formed, also allowed the freeing up of other areas where the relationship between constituency and ‘essence’ made it difficult to think about alliances, or led to the setting up of uncrossable boundaries – in particular in relation to race and gender. Kobena Mercer aptly describes Hall’s moves in this direction as a ‘constructionist trajectory’. These theoretical insights helped release a whole generation of thinkers and activists from the temptations of fundamentalism. They also fed into further creative developments within cultural theory that aided the understanding of the politics of subjectivity and identity – but this is another story.

In the late 1970s and 1980s, the journal Marxism Today became one of the main forums for debates about how to understand the changes that were taking place as the post-war consensus was being replaced by a new hegemonic force. By the time Martin Jacques became editor of Marxism Today in 1977, the journal had become a centre of Eurocommunism within the British communist party. Hall, Michael Rustin and Doreen Massey – subsequently the three founding editors of Soundings – all wrote for Marxism Today, as did many other Soundings contributors. This did not mean that they signed up to every aspect of the Marxism Today’s project – none of them were communists – but they recognised that the journal was a forum for some of the debates in which they were interested.

Although Marxism Today had a reputation for its engagement in popular culture, its coverage of these areas was not its main strength. Where it was at its best, and where it differed from New Left Review was in its efforts to analyse the present, the conjuncture and the state of the political and cultural forces that were engaging on the ground in British society. In particular, Marxism Today was concerned to understand the phenomenon of Thatcherism. This is where writers such as Hall made a massive impact. As Hall and others argued, Thatcherism needed to be understood as a moral, not just as a political force. This preoccupation with the present conjuncture of British politics is shared by Soundings, though I would argue that Soundings is more open to the ‘constructionist trajectory’ than Marxism Today (which closed in 1991) ever was, and to questions of gender and race more generally.

Soundings

Soundings was started in 1995 – after Thatcherism had lost its popularity and Tony Blair’s Labour was clearly going to form the next UK government. The founding editors – Hall, Rustin and Massey – felt that this was a time of opportunity for left renewal and they wanted to intervene to restate a New Left perspective on political and cultural life. (This was before the Blair clique had become so firmly ensconced in the party, presiding over nothing more radical than neoliberalism in its social-democratic variant.) The journal’s ‘overriding interest’ would be ‘in the relation between political thought and action … [and] the larger social processes which shape and limit their possibilities’. Within this, it would be looking for potential sites of resistance within civil society: ‘the democratic revolution is a broad river, never containable within the confining channels constructed by politicians’. And it invoked ‘a politics beyond politics’.

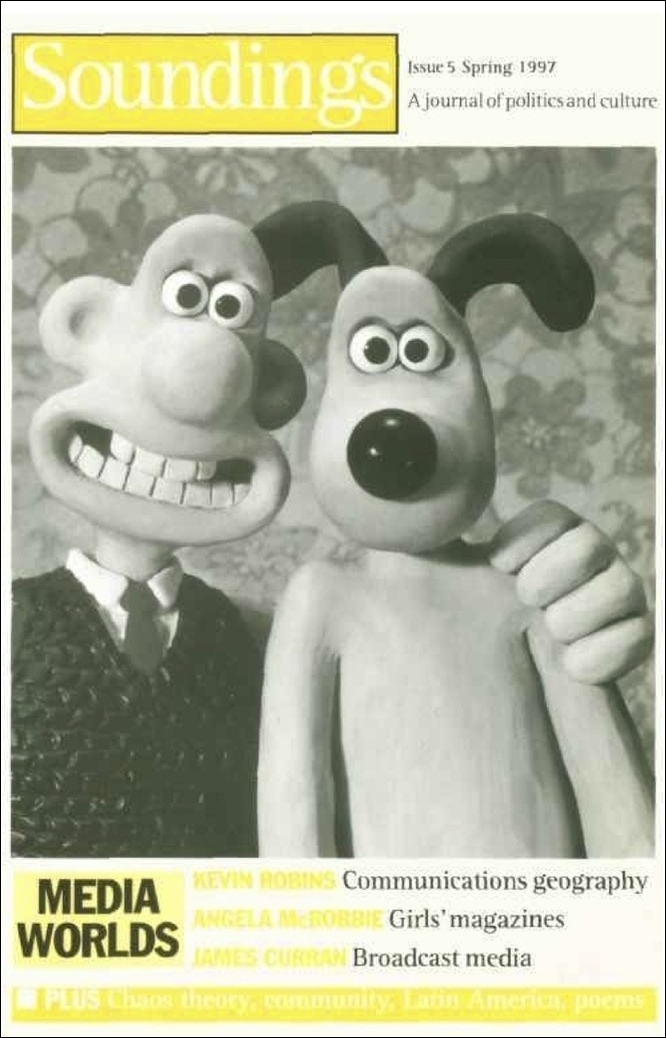

Soundings 5 (1997)

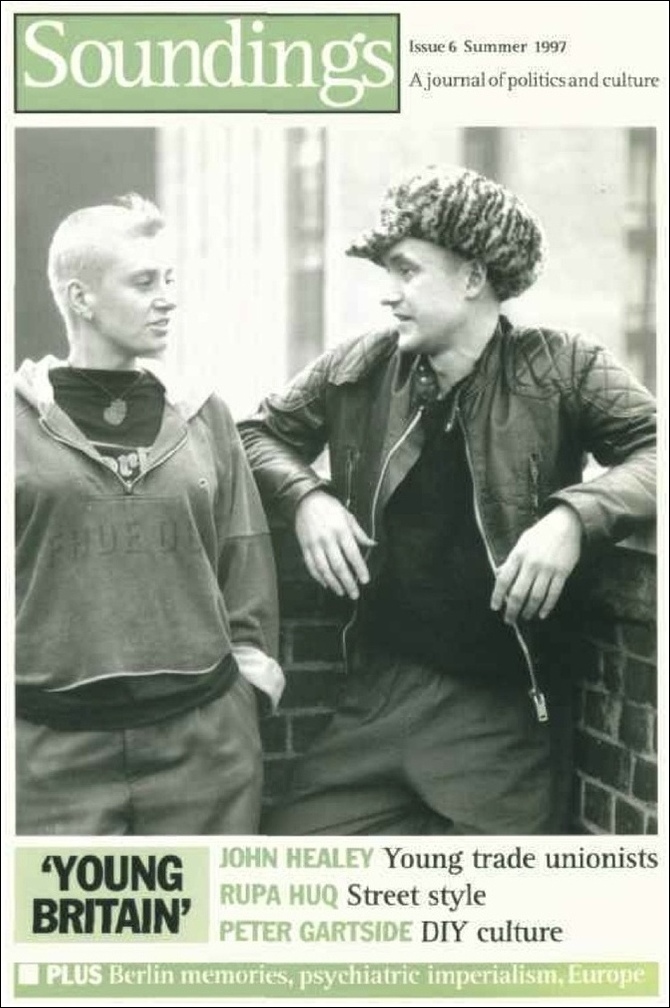

Soundings 6 (1997)

This has remained an enduring theme, despite the loss of Stuart Hall (in 2014) and Doreen Massey (in 2016), who are both greatly missed. For example, since the very beginning, a continuing preoccupation of Soundings has been in analysing the nature of neoliberalism as a totality. This was reflected in our project After Neoliberalism: the Kilburn Manifesto, which, as well as considering the neoliberal economy also considered the wider effects of neoliberal culture. For example it looked at the infiltration of its languages into daily life, as in Doreen Massey’s article on ‘vocabularies of the economy’, while a chapter by Stuart Hall and Alan O’Shea explored further the idea of common sense – particularly the common sense view that society can be understood as a market. Since then we have started a series called ‘Soundings Futures’, which seeks to build from an understanding of the dominance of neoliberalism across public services, using it as a starting point for re-imagining alternatives. A third series, still in its early stages, ‘Soundings Critical Terms’, aims to revisit and re-articulate some of the main ideas that have informed the political thinking of the editorial collective. It was kicked off by an article by Deborah Grayson and Ben Little on conjuncture.

Because of the journal’s sense of itself as being located within a specific tradition of thought, we are very conscious of the issue of intergenerational dialogue. As has been touched on this article, there is an awareness of the generational ups and downs of a particular strand of ideas, thinkers and activists. One way this has manifested itself is in a series of articles about generation, the most recent of which is ‘Generation: The politics of patriarchy and social change’ by Ben Little and Alison Winch. Another way is in our efforts to engage with the new left generation galvanised by Jeremy Corbyn’s leadership of the Labour Party. We try to do this in a spirit of sharing ideas that might be of use rather than knowing all the answers. Having ourselves learned from years of inter-generational dialogue, we want to continue the process.

Soundings 10 (1998)

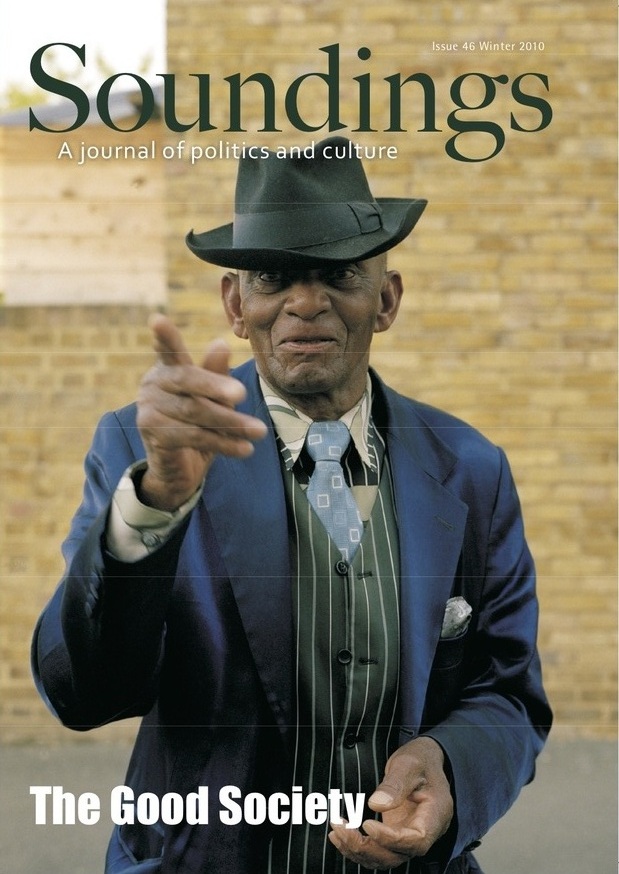

Soundings 46 (2010)