An era of constitutional reform?

It is no coincidence that in both France and the US, nations uniquely proud of their democratic traditions, debates are emerging about constitutional reform. Recent articles explain why.

Less encouraging are signs from France. Polls for the presidential elections in April 2022 show the far-right penseur–provocateur Éric Zemmour level-pegging with Marine Le Pen at 15%. The combined leftwing vote, including the Greens, meanwhile languishes at 20%. Though Macron still leads, his winning formula in 2017 – ‘neither right nor left’ – won’t secure him the same comfortable majority this time around.

As Michäel Fœssel writes in Esprit, Macron’s liberal revolution quickly ran up against the wall of the gilet jaunes and COVID-19. Four years later, a reconciliation with liberalism is no longer on the agenda. But piling on state power cannot be the answer. Rather, Macron must engage with popular grievances at the institutional level. According to Föessel, increasing democratic participation means nothing less than rethinking the constitution of the Fifth Republic.

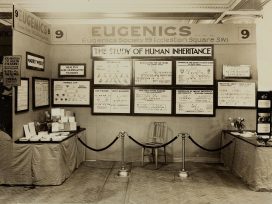

Photo by Stefan jaouen, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Could liberal democracies be entering an era of constitutional reform? The discussion in the US would certainly suggest so. In a fascinating and important issue of Public Seminar, Aziz Rana argues that the habit of treating the US constitution as the apotheosis of democracy is directly connected to America’s emergence as global hegemon.

But as democratic dysfunctions within the nation become ever more apparent, the culture of constitutional veneration is being questioned. ‘Both the legitimacy of the American Century and of the American constitutional model are facing profound pressure today,’ writes Rana. ‘Given how entangled the two are, it makes sense that just as they emerged together, they are also breaking down together.’

Anthony Barnett, co-founder of openDemocracy and campaigner for constitutional reform in the UK, responds. Constitutional piety reveals an ignorance of Trumpism’s anti-elitist appeal, Barnett claims. ‘There are at least two, linked issues at stake in any effort to create a democratic polity in the US. The first is over who is included in the “we” of “We, the people”. The second is over the role of big money and dark money in controlling policy outcomes.’

But is constitutional reform even enough? Remarkably for two professors of constitutional law, Samuel Moyn and Ryan Doerfler argue that the ‘myth of fundamental law’ must be relinquished. ‘In the midst of a new racial uprising and calls for a “political revolution” only very recently in the air, why pretend that our political disputes turn on the “best” reading of an eighteenth or nineteenth century text instead of the sort of “freedom” or “equality” we as a people want our society to embody today, here and now?’

For something completely different, we strongly recommend filmmaker Petronella Petander’s electrifying essay about loss, dependency and addiction, first published in the Swedish journal Glänta. Here is just a sample, describing the author’s return from rehab: ‘By the time I came back, the world I had left no longer existed. The tiny fragile hope for myself, which had just started to sprout in me, was lost the moment the immense insight struck me: I had missed the digitalization of society.’

If this doesn’t tap into to an early twenty-first century Urangst, what does?

This editorial is part of our 17/2021 newsletter. Subscribe to get the weekly updates about our latest publications and reviews of our partner journals.

Published 20 October 2021

Original in English

First published by Eurozine

© Eurozine

PDF/PRINTNewsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Related Articles

For a strong start into the second season, we talk about corruption in the EU. In the basement of the European Parliament we talk Italian mafia, Orbán’s son-in-law, and the misuse of public funding in member states with MEPs.

Pronatalism has become a populist vote winner for right-wing parties in Central and East European countries. Demographic imbalances, involving youth migration, ageing populations and immigration resistance, have sparked a series of baby-making policies. But are financial incentives in Hungary, Poland and Serbia enough to reverse the trend of decreasing birth rates?