In ‘Merkur’, the return of the rabble: why populism is all about undesirable feedback – and how to break the loop. Also: New Right politics of history in the recent Hohenzollern restitution controversy.

Perhaps predictably, its function has been replaced by the term populism: ‘Whatever one rightly or wrongly brands as populism, it is above all about undesirable feedback – a disruption of the communicative structure of modern society that renders feedback improbable. Ever since the Enlightenment, the rabble polemic has appeared whenever the elite segregation of society has become unstable. So-called populism is above all that which frustrates the neat hierarchization and control of communicative spheres.’

Given that populism is practically synonymous with right-wing radicalism, there are good reasons to oppose it. The question, however, is how to do so. Representative democracy, Widder argues, is above all a way of reproducing social divisions: today, elected politicians have overwhelmingly professional backgrounds, while the ‘opinion industry’ ensures that the electorate makes the right decision. Populism is the declared enemy of this type of politics.

The introduction of a second chamber of representatives elected via lottery could provide a breakthrough: ‘Only through coincidence can the people come into itself.’

The new right and the mantra of objectivity

That Germany’s New Right strives for quasi-Gramscian cultural hegemony has become something of a truism. But Niklas Weber shows in striking detail how New Right attempts to re-mythologize and de-criminalize twentieth century German national history have played out in the ongoing controversy over the claims of the descendants of the Hohenzollern dynasty to the restitution of artworks confiscated after 1945.

Weber demonstrates how the publications of Benjamin Hasselhorn, a young historian called by the CDU as an expert witness in a parliamentary hearing on the issue at the beginning of 2020, reproduce a revisionist view of German history introduced by the influential New Right thinker Karlheinz Weißman twenty-five years ago.

‘Resolutions against the right are a nice gesture and discourse analysis is certainly helpful. But history is written by people who need to be contradicted openly’, argues Weber. As long as New Right academics hide their politics behind the ‘mantra of objectivity’, criticism can be deflected as partisanship and even slander; critics, on the other hand, are caught in the logic of ‘demasking’ and ‘denunciation’.

Instead, engagement with New Right historians must take place at a substantial level. ‘Talking to the right’ – a controversial slogan in Germany, in connection with the dilemma over how to engage publicly with the AfD – ‘might be a bad idea on talk shows, but it is high time that academia begins doing so,’ comments Weber.

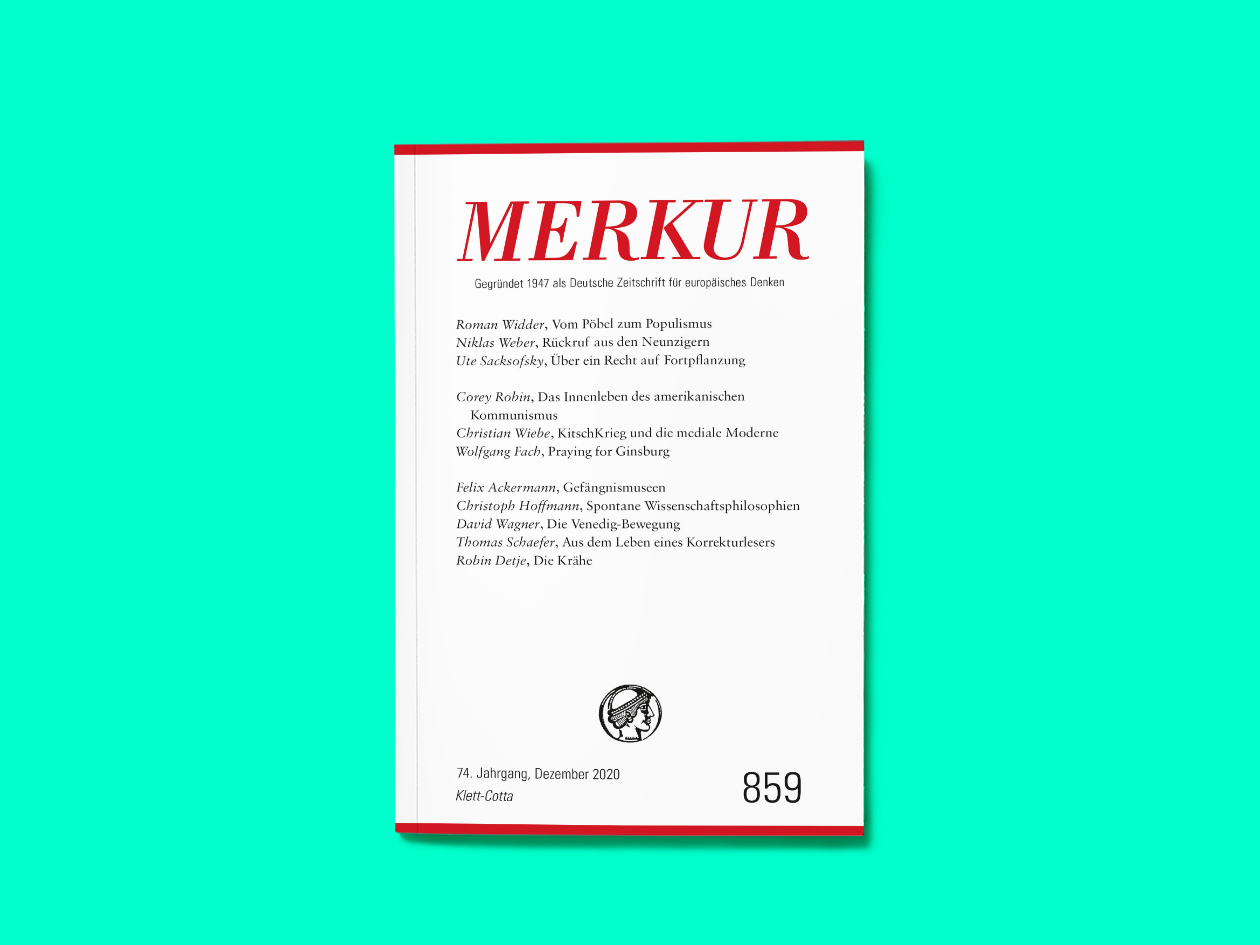

This article is part of the 22/2020 Eurozine review. Click here to subscribe to our weekly newsletter to get updates on reviews and our latest publishing.

Published 21 December 2020

Original in English

First published by Eurozine

Contributed by Merkur © Eurozine

PDF/PRINTNewsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Related Articles

France risks becoming ungovernable. While Macron’s autocratic style is much to blame for the current impasse, the fundamental problem lies in the development of the parties and party elites.

The Courts have acquiesced, the populace is compliant and the Democratic Party is splintered. Without any way to make their opposition felt, Trump’s opponents’ only hope is that the economy will cause MAGA voters to rethink.