Albania: Obstructed democracy

Reforms that would bring Albania further towards EU accession remain hampered by corruption and lack of political will. Prime minister Edi Rama, now into his third term and without a serious challenger, embodies the contradictions of the West Balkan country’s hybrid democratic system.

Albania made the transition to democracy back in the early 1990s, but has been struggling to overcome various political, social, and economic challenges ever since. Despite some progress in integration with the European Union, the West Balkan country remains a long way from meeting the necessary institutional standards for democracy and the rule of law. Positioned in a highly strategic part of Europe, Albania has been a NATO member since 2009. But it remains plagued by endemic corruption and organised crime, despite encouragement from EU and US officials to implement reforms to the judicial system that would make the country’s criminal law more even-handed.

Albania was granted EU candidate status in June 2014, but it took another six years for the country to officially begin accession negotiations with the EU. During that time, the country underwent several reforms. Although progress was made in fighting corruption, including the establishment of a specialised anti-corruption agency and the introduction of new measures to increase transparency and accountability in government, Albania’s progress on institutional reform has been hampered by a lack of political will and entrenched interests. There are concerns that recent reforms may not be fully implemented, and that political parties continue to resist meaningful change.

Meanwhile, Albanian politicians continue to grapple with issues of nationalism and foreign influence. In recent years, the country has been affected by the increased spread of pro-Russian propaganda and disinformation in the Western Balkans, with media reports of instances of Albanian politicians allegedly receiving Russian money and support. This has created a growing sense of mistrust towards western institutions and values.

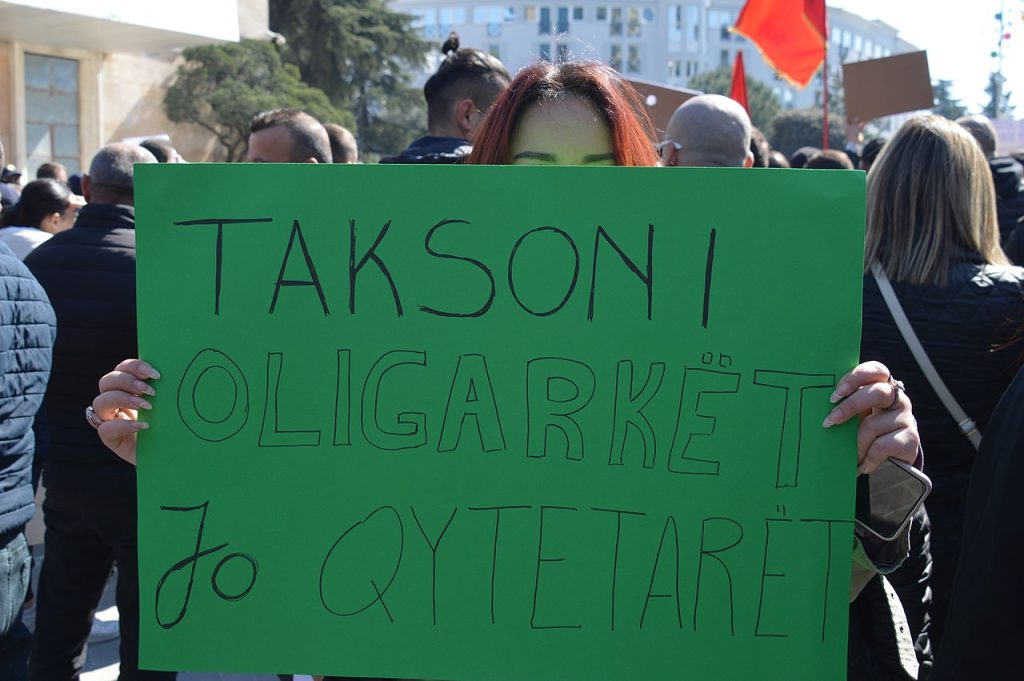

Sign calling for taxes ‘on oligarchs not citizens’, Tirana 2022. Source: Wikimedia Commons

A tale of two parties

For the last three decades, Albania’s political landscape has been dominated by two major parties: the Socialist Party (SP) and the Democratic Party (DP). These parties have taken turns at the reins since the fall of communism, and their rivalry has led to a polarised political environment that has hindered institutional reform and democratic consolidation. The division of powers in Albania is also problematic, with the executive branch exerting significant influence over the judiciary and other independent institutions. The lack of separation of powers undermines the rule of law and makes it difficult to hold those in power accountable.

Elections in Albania have been followed with political parties trading accusations over irregularities and allegations of vote buying and manipulation. Since 2013, the Socialist Party has been the ruling majority, with its leader Edi Rama serving as prime minister. Rama has consolidated his authority within the country by retaining his position for a third term following general elections in April 2021. During his extended period in power, several investigations, media reports and international organisations have highlighted cases of high-level corruption in Albania that seriously affect rule of law and the economy. This has resulted in soaring emigration, with thousands of Albanians, many of them professionals, abandoning the country, mostly bound for the EU and the UK.

On the other side of the political field, the Democratic Party represents a weak opposition. The party has been riven by several internal conflicts in recent years, culminating in 2021 with the designation of former prime minister, former president and former Democratic Party chairman Sali Berisha and his family as ‘personae non grata’ by the US Department of State and the UK. Lulzim Basha, then the party leader, subsequently expelled Berisha from the party’s parliamentary group. But with Basha now out of the picture following his resignation last year, Berisha is launching a movement to revive the Democratic Party and attempting to establish himself as undisputed party leader for a third time, declaring – without providing any evidence – that his US/UK travel ban is part of a Rama-Soros lobby.

As a result, the party has split into two factions: the ‘pro-Berisha’ group, supported by the majority of democrats, and the ‘anti-Berisha’ group, fewer in number but recognised by the courts as the official Democratic Party. Both factions ran for the municipal elections that took place on 14 May 2023. The DP split enabled the SP to win 53 out of 61 municipalities, not only in key cities but also in traditional Democrat strongholds. The Socialists also managed to win a majority of city councils nationwide. However, the official turnout was 38 percent, one of the lowest ever registered in the country’s history.

According to Roland Qafoku, a political analyst and expert in Albanian electoral processes, the SP is confident of winning its fourth mandate in a row in the 2025 general elections. While the success in the local elections is an ‘unprecedented accomplishment’ for a party in its tenth year in power, Rama and the SP ‘are greatly advantaged by a Democratic Party in an absurd, divided and fragmented situation’.1

Corruption and foreign influence

EU integration and closer ties with the West have been part of the agenda and discourse of both main political parties over the last 30 years. Public attitudes in Albania towards liberalism, the EU and the West are generally positive, with most people supporting EU integration and closer ties with western countries. In July 2022, Albania officially opened negotiations on accession to the EU, a process that involves the adoption of the 35 chapters of the EU acquis in the national legal system and the implementation of legal, political, economic, administrative and other necessary reforms. At present, Albania is still in the screening phase, which is the first step of the accession process.

At the start of the war in Ukraine, Albanian officials and the Albanian government were among the first to take a stand against Russia’s aggression. Parades in support of Ukraine were organised by Albanian politicians, and even the name of the road in Tirana where the Russian Embassy was located was changed to Free Ukraine Street, prompting the embassy to relocate.

In September 2022, Albanian Prime Minister Edi Rama addressed the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (PACE), saying that ‘the faith of Albania and its European destiny is our anchor to the future’. But while Rama makes efforts to establish good relations with various European leaders, he also likes to play on the wider geopolitical stage. His close ties with Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdogan are well known, but recently he has developed a friendly relationship with Serbian president Aleksander Vučić, sparking critical reactions in Albania and Kosovo.

In September 2022, Rama told the Austrian newspaper Die Presse that no more pressure should be put on Serbia to impose EU-compliant sanctions on Russia for its aggression in Ukraine, given Serbia’s economic reliance on Russia and support for Vučić from the pro-Russian part of the population. On 6 December 2022, Rama repeated this position at the EU-Western Balkans Summit in Tirana. At the same time, the Albanian prime minister insisted that Russian influence in the region was real and that it was important to keep Moscow out of the Balkans.

Yet Rama himself has been implicated in connection with the case of Charles McGonigal, a former FBI counterintelligence chief indicted by prosecutors in New York and Washington on charges of money laundering and violating US sanctions by working with Russian oligarch Oleg Deripaska, a close ally of Russian President Vladimir Putin. By the time McGonigal allegedly started working for Deripaska, who is under US sanctions, he was already deeply involved in other secretive dealings with the Albanian prime minister. According to the indictment, in 2018 McGonigal encouraged the FBI to open a criminal investigation into an American lobbyist acting on behalf of the Democratic Party of Albania for receiving Russian money and funds, raising concerns about Russian interests trying to influence the prime minister’s opponents. The source of some of the incriminating information against the lobbyist was allegedly traced back to Rama’s office.

During the 2021 election campaign, both political parties seized the opportunity to showcase their pro-western and pro-European Union stances. This year’s municipal election campaign was no different, with Rama painting Berisha as a black sheep, while proclaiming himself as the face of EU integration.

Despite being designated ‘persona non-grata’ by the US Department of State and treated as a pariah by US, EU and UK officials and representatives, Berisha seems to have the support of the majority of Albania’s Democrats. While this is still not enough support to be able to defeat Rama, it has generated and exploited public scepticism concerning the democratic standards of the West. There are also concerns about pro-Russian attitudes and foreign influence in Albania’s political landscape. Russian propaganda and disinformation have been spreading in the country, fuelling anti-western sentiment and undermining the legitimacy of democratic institutions.

‘In fact, news and sporadic cases of a Russian intention to land in Albania started 15 years ago’, says analyst Qafoku, highlighting the purchase of houses in Saranda and other cities by Russian ‘tourists’, as well as an increase in the numbers of Albanians studying in Russia. Citing Russian links to a 2017 election meddling scandal involving a Trump aide and the Albanian DP, as well as Russian state-run media’s sensationalist and partisan coverage of opposition protests in Tirana the same year, Qafoku describes the situation as at best unclear. ‘The political situation has leveraged scepticism towards the West’, he says. ‘It is the first time ever that the DP is portrayed as anti-American. This is unprecedented in the diplomatic history between the two countries.’2

Cybersecurity at risk

With the EU focused on the war in Ukraine and its economic consequences, the Balkans seem to have attracted increased attention from third-party countries keen to influence the region’s politics. In the second half of 2022, Albania endured a series of cyberattacks, devastating the country’s critical computerised public and private infrastructure. Using ransomware, hackers managed to shut down government websites, causing catastrophic disruption to the Albanian public administration (which had been largely digitised to avoid slow and corrupt bureaucratic processes) and throwing the lives of citizens into disarray.

The hackers also harvested and shared confidential data such as the identities of numerous undercover Albanian intelligence officers, the emails of the director of the State intelligence Service, and sensitive private information, including over 17 years’ worth of data about entries to and exits from the country and bank customers’ financial records. The government’s Total Information Management System was also targeted, causing severe disruption to the functioning of the executive branch.

Rama accused Iran of carrying out the attack and immediately severed diplomatic relations. Investigators believed that Albania had been targeted by Tehran in retaliation for its sheltering of thousands of members of Mojahedin-e-Khalq (MEK), a once violent Iranian opposition group and now Iran’s biggest organised opposition faction. The MEK members have been resident in a fortified camp in the Albanian town of Manez since being evacuated from Iraq in 2016.

Iranian diplomats were expelled from the country within 24 hours and sanctions levied against those who were purportedly responsible. At the World Economic Forum in Davos in January 2023, Rama reported that thanks to the assistance of Microsoft, the FBI and other experts, they had been able to prevent the complete shutdown of systems and the deletion of all data, which he said was the primary aim. Despite the controversial decision to permit the MEK to establish a base in Albania in 2016 and potentially form a government in exile, Rama remains steadfast in defending the move.

The magnitude, range, complexity and aggression of the cyberattacks on Albania, along with the ransomware operations carried out by cybercriminals based in Russia, have led some to believe that Iran did not act unaccompanied. While Albania was under attack, other countries in southeast Europe – including Montenegro, Bulgaria, Kosovo and North Macedonia – were also being targeted by Russian-speaking groups.

The cybersecurity issue has become an important concern, affecting not only people’s private lives but also national security and elections. In 2021, just before the parliamentary elections, a database called the ‘patronage list’ containing the personal information of 910,000 Albanian voters was leaked to the media. Allegedly prepared by the Socialist Party and shared via WhatsApp and other channels, the dataset contained information such as voters’ ID number, name, date of birth, phone number, immigration status, birthplace, employer, electoral registration and even voting behaviour. The OSCE report on the 2021 general elections in Albania stated that the leak had damaged the confidence of the electorate, including the secrecy of their votes. Rama denied that the Socialist Party was responsible for the leak.

The country’s fragile cybersecurity system has made it vulnerable to further cyberattacks, as a significant amount of government data and citizens’ personal information has already been exposed, raising serious concerns about Albania’s national security and the potential for Russia, China and other countries to take advantage the situation.

The long road to justice

The overhaul of the judicial system, the most prominent and contested of the reforms initiated in 2016 with the support of the EU and US, promised to be a solution to pervasive corruption and criminal activity. Specifically, the reform aims to institutionalise a new judicial architecture and vet a significant number of members of the existing system. All the country’s social, political and governing actors have committed to these changes – at least rhetorically. Nevertheless, seven years after the launch of the reform, limited progress has been made.

Every step of the reform has been delayed, obstructed and sometimes sabotaged by powerful actors who have traditionally controlled the system and stand to lose from an independent judiciary. The Special Anti-Corruption Prosecutor office (SPAK), created as a new body as part of the judicial reform, seems powerless to counter the level of money laundering, drug trafficking and other criminal activity that is repeatedly flagged in the country.

This contradiction between rapid institutional reform and resistance to implementation marks the country’s entire political and economic transformation and is a hallmark of the Albanian hybrid democratic system.

One explanation is the ongoing emigration of skilled workers that has deprived the country of the expertise and professional credentials necessary to drive forward substantial reforms. During the last 10 years, unofficial data shows that more than half a million Albanians have left their homeland in the hope of building a future for themselves elsewhere, emigrating mostly to the EU countries and UK. Between 2015 and 2020, Albanians topped the list for the number of asylum applications submitted to EU member states, ranking second only to applicants from war-torn Syria.

A 2018 study by the UNDP places Albania top of the emigration world rankings for individuals with tertiary education. The majority of those who leave are part of a talented generation of trained professionals, scientific experts and young academics who would otherwise have formed the backbone of the Albanian middle class.

Despite the significant challenges, Albania needs to continue its efforts to reform its electoral system, fight corruption and strengthen the independence of its judiciary and other institutions. At the same time, there is a need to address the underlying issues of foreign influence that are undermining the country’s democratic development. Albania’s prospects for EU integration depend on its ability to overcome these challenges and establish a stable and inclusive political system that serves the needs of all its citizens.

Published 5 June 2023

Original in English

First published by Eurozine

© Ina Allkanjari / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTIn collaboration with

In focal points

- Living dead democracy

- Why Parliaments?

- Spelling out a law for nature

- No more turning a blind eye

- The end of Tunisia’s spring?

- Protecting nature, empowering people

- Albania: Obstructed democracy

- Romania: Propaganda into votes

- The myth of sudden death

- Hungary: From housing justice to municipal opposition

Newsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Related Articles

Viewing authoritarianism as a political trend overlooks the damage it can cause. The devastation ‘illiberal democracies’ are inflicting on cultural and media sectors show just how difficult it is to recreate something once it has been taken apart. Eurozine partners discuss ways to sustain journalism at the 32nd European Meeting of Cultural Journals.

Back on the Trump track

Topical: US Election

War, women’s rights, deportations and democracy: what’s at risk as Trump returns? Eurozine’s topical reads on what to expect of the power shift in the US.