As emergency services and thousands of volunteers continue rescue and clean-up efforts in Valencia after parts of the city and surrounding areas were devastated by flash-flooding in late October, questions are mounting over the handling of the deadliest natural disaster in Spain’s recent history. At least 220 people were killed by the relentless floodwaters, which destroyed homes, wrecked cars and left whole districts covered in mud. Dozens are still missing.

In the wake of the disaster, Spanish media were full of headlines such as ‘Floods in Valencia leave over 200 dead and countless missing in under 48 hours’, but these were not entirely accurate, since they failed to acknowledge the political and economic realities that were so responsible for the devastating human cost of October’s floods.

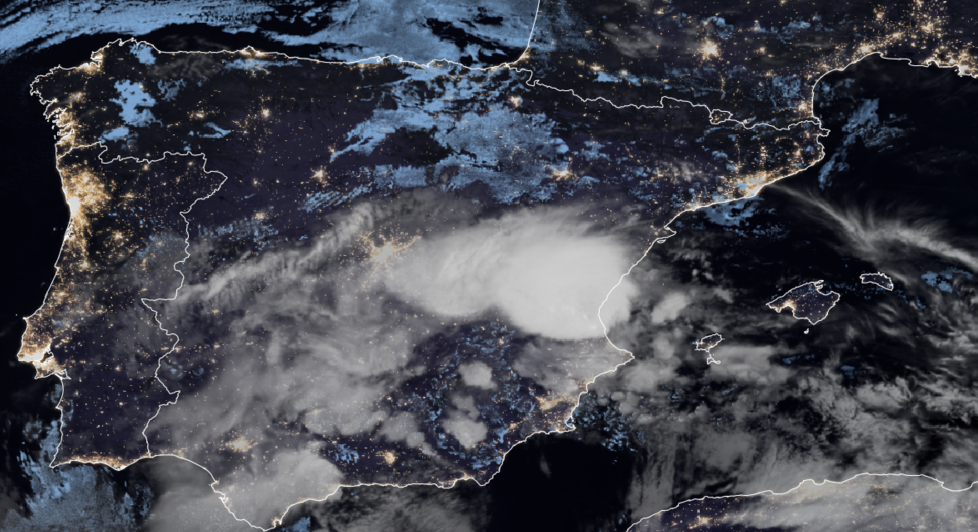

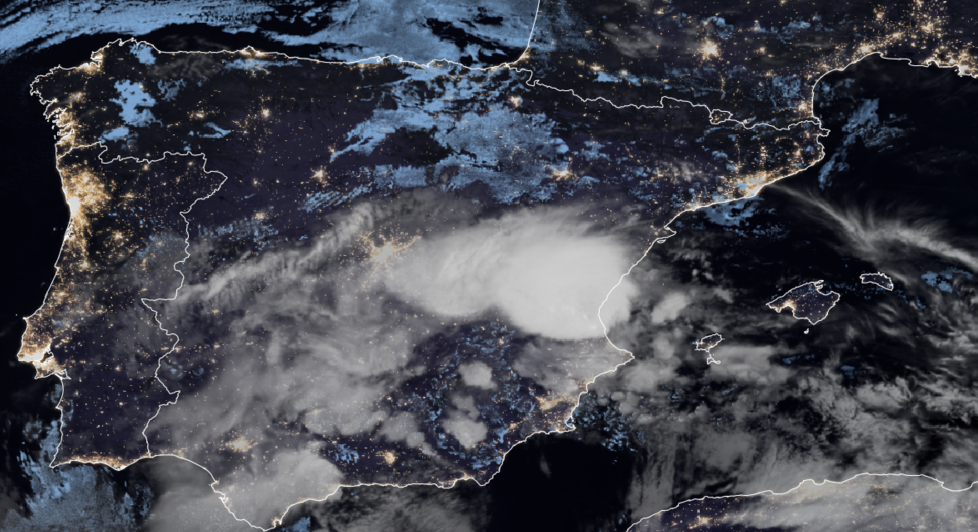

The catastrophe was caused by what Spanish meteorologists call a DANA (Depresión Aislada en Niveles Altos, or Isolated High-Level Depression), a cold air mass that drops onto warmer air, causing intense atmospheric disruptions and torrential rain. These weather patterns are common in Spain’s Mediterranean coastal regions, especially in September and October. As the water temperature of the Mediterranean rises, DANAs are becoming increasingly more common and more intense, triggering stronger, denser storms.

Government leaders – local, regional and national – are well aware of this. But even if they weren’t, Spain’s Meteorological Agency (AEMET) had been warning about this specific DANA’s approach to Valencia days before it hit. On the morning of the disaster, at 7:30 a.m., AEMET issued red alerts for ‘unusual phenomena of exceptional intensity, with a very high level of risk to the population’. Despite this, it was not until 1 p.m. that Carlos Mazón, president of the right-wing Valencian regional government, urged drivers to take care on the roads, and not until 8 p.m. that the Civil Protection Service sent a warning message to all citizens advising them to avoid any type of travel. By that time, however, thousands were already trapped in their cars, homes, or workplaces – many were forced to climb onto the roofs of shops or petrol stations, waiting for rescue from emergency services that, in many cases, were unable to reach them.

To say this alert came too late is a tragic understatement. Earlier action not only could have saved many lives, but also prevented the anger and hopelessness felt by a society that, once again, finds its safety compromised in favour of capitalist interests.

Satellite view of the DANA over Valencia on 29 October at 6:30 a.m. Image by EUMETSAT via Wikimedia Commons.

An ever more vulnerable world

The DANA storm that wreaked such destruction on Valencia did not come out of the blue. Interactions between natural processes and human activity within the current productive model have intensified the frequency and severity of extreme weather events and unprecedented climate changes.

Recent studies assert that the anticipated escalation in greenhouse gas emissions is predicted to exacerbate global warming and subsequent climate change, increasing the likelihood of severe and irreversible impacts on people, infrastructure, and ecosystems. Discussions around climate vulnerability have moved beyond the realm of the purely scientific and have gradually become recognized as a crucial matter in global governance and societal well-being, making it a paramount consideration in addressing climate-related risks not only from a scientific perspective but also in terms of policy-making and building community resilience.

There is no single, universally applicable definition for climate vulnerability; it is a complex concept influenced by various fields. The 6th Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) offers a widely accepted framework that defines climate vulnerability through four essential components. These are: risk (the potential for adverse outcomes in human or ecological systems due to the interaction of climate hazards with exposure and vulnerability); exposure (the presence of people or ecosystems in areas potentially affected by climate hazards); adaptation (adjustments made by human and natural systems to minimize harm and capitalize on opportunities presented by climate change); and resilience (the capacity of systems to cope with and adapt to hazardous events while maintaining their core functions).

According to this definition, climate vulnerability is viewed as the propensity to be adversely affected by climate impacts, which includes exposure to harm and limited adaptive capacity. The understanding of vulnerability has therefore evolved from a purely biophysical focus – emphasizing exposure to climate hazards – to a broader approach that incorporates social and contextual factors.

An avoidable tragedy

Effective risk management strategies are there to mitigate the potential adverse outcomes of future extreme weather events, such as those experienced during the DANA. This includes identifying vulnerable populations and infrastructure in order to anticipate and reduce their exposure to such hazards. However, one of Carlos Mazón’s first actions upon taking office was to dismantle Valencia’s Emergency Unit, which by the time of this DANA, no longer existed.

In a world where natural disasters are increasingly common, the reasoning behind this decision is hard to fathom. Given that Spain receives substantial funding for climate adaptation projects and loudly proclaims its commitment to use these funds wisely in the most vulnerable areas, the question remains: where is this money actually going? Why do the most vulnerable areas keep getting more vulnerable?

This is not the first DANA that Spain has faced, and lessons learned from previous events highlight that one of the most important adaptation measures is to effectively warn the population to stay at home. Furthermore, Article 21 of Spain’s Law 31/1995 on Occupational Risk Prevention establishes that employees have the right to interrupt their activity and, if necessary, leave the workplace when they consider there is a serious and imminent risk to their life or health. This right is specifically outlined in Section 2 of the article, which states that an employer cannot require employees to remain in a workplace where dangerous conditions are present and cannot be avoided.

Yet countless reports indicate that residents in the affected areas received alerts on their phones from the Civil Protection Service advising against movement only after several hours of rainfall, by which time many people were already trapped in buildings and vehicles which had been swept away by the floodwaters. Moreover, many companies did not consider the situation serious enough to allow their employees to stay at home. IKEA kept its employees trapped in warehouses as the floodwaters rose, while Mercadona, the largest supermarket chain in Valencia, instructed its workers to keep working and UberEats forced its couriers to continue deliveries through heavy downpours on bicycles and scooters. These decisions exposed hundreds, if not thousands, of additional people to the disaster in Valencia and led us to where we are now.

But adaptation measures do not only encompass immediate responses; long-term planning is of at least as much importance, if not more. For many years, Spain’s coast was subject to uncontrollable urbanization, including flood-prone zones, which are the areas now among the hardest hit. While a Spanish law passed in the late 1980s limited coastal construction, the new regional government in Valencia has recently adopted legislation that relaxes these restrictions. For instance, just two days before the DANA, the government approved a measure to allow hotels to be built 200 metres from the coast instead of at the previous limit of 500 metres.Furthermore, a capitalist system that prioritizes productivity over safety has proven to be more dangerous to people than a DANA itself. There should be no ‘regardless of the consequences’, and economic growth is not the ultimate goal. We live in a system in which we have internalized certain power structures that lead us to accept these logics, often without question. Is risk a necessary condition for economic success? If we know it is not, then why do we perpetuate these inhumane models? This is not to criticize in the slightest those in Valencia who went to work at their employer’s insistence, but to remember Michel Foucault’s maxim that ‘where there is power, there is resistance’, and resistance is there for us to harness.

When it comes to natural disasters, community awareness and support systems are as crucial as resilient infrastructure and housing. Vulnerability does not hit everyone the same way – gender, age, class and origin, among others, are aspects that create huge abysses between people’s exposure and adaptive responses to climate hazards. Vulnerable groups must be identified and supported to improve their adaptive capacity, ensuring that interventions are inclusive and equitable. Moreover, as a whole, communities armed with a heightened awareness and understanding of climate change are not just better prepared to respond to its challenges but also empowered to mitigate risks and enact appropriate adaptation strategies.Conversely, a lack of awareness or misconceptions can amplify vulnerability and impede effective response efforts, underscoring the importance of communal knowledge. By identifying knowledge gaps and misconceptions, policymakers can tailor communication and education initiatives to address specific needs and foster informed decision-making at the local level, thereby playing a crucial part in the process.

According to Jorge Olcina, a climatologist at the University of Alicante, there is a lack of public education on disaster preparedness in Spain, unlike in countries like the US, which has a hurricane education programme [1]. He points out that, ideally, school lessons should have been cancelled and non-essential work suspended in Valencia, acknowledging that such measures are costly but emphasizing that ‘the price we’re paying now will be even higher’. Parents were in fact advised not to send their children to school, yet they themselves were not advised not to go to work. This reflects a troubling priority: children have no impact on GDP, so the decision to keep them out of school appears to be little more than a token gesture. Real emergency measures would have involved shutting down almost all activities, including those that clash with economic interests.

Acknowledging systemic neglect

When I mentioned earlier that headlines like ‘Floods in Valencia leave over 200 dead and countless missing in under 48 hours’ are not entirely accurate, I didn’t mean it in the literal sense. However, one could certainly ask for a little more precision and accountability in reporting. The phrase ‘Floods in Valencia’ carries a tone of neutrality, as if October’s catastrophe were just a natural occurrence. But what I am trying to emphasize with this cluster of desperate words is that these events are not merely the result of ‘water’. They are the culmination of systemic failures, neglect, and human decisions that put lives at risk. This is the outcome of a socio-environmental catastrophe managed by climate-change deniers and economic neoliberals – that is, the very same people who have intensified it.

Each statistic represents a life; a story cut short; a community left shattered. Instead of framing events like the Valencia floods as an unfortunate act of nature, we should acknowledge the human agency behind these disasters – how urban planning choices, environmental neglect, and economic priorities have all contributed to this. Some may seek comfort in believing these events are inevitable, avoiding the painful guilt that arises from acknowledging our complicity.

However, this perspective hinders our ability to anticipate and prevent future tragedies. It is essential that we take responsibility for our role in these situations, since they are, to a significant extent, preventable. Together, we can work towards a future that values safety and resilience above productivity, encouraging a humbler understanding of the nature around us and a braver coexistence based on community and mutual support.