Drawings

He looks at the windowpane in the corridor. She says: “I no longer recognize you.” The description, a paragraph from Marguerite Duras’ text Love, could hardly be more offhand. Just as language sometimes succeeds in creating pictures of what is not described, so drawings occasionally speak of what lies outside the depicted. Paradoxically, this is often the case when the retelling of a situation, be it in text or images, stays very close to each object represented, to the objective. The windowpane, the corridor, his look, what she says: four elements that in Duras already form a story, precisely because they are fragments, even if part of a larger text.

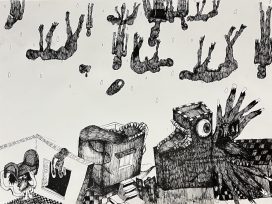

Two men in suits, a handshake, in the background a cement mixer and rubble, the hand of the one man lies firmly on the forearm of the other. Both heads are cut off, not in the picture: That is a picture (translated into text) by Barbara Holub, entitled “Shaking shoulders and patting hands”. A millimetre thick line in black ink on white paper serves to represent a situation in outline; the picture itself appears to be very straightforward, almost conventional, as if out of a painting book. In fact, it makes use of a technique that runs counter to the conventions of the medium of drawing, insofar as it undermines the way drawing is supposed to be read, its visual habits and its hierarchies of information: the “harmless” scene of the handshake recalls the more or less legal deals made in the building and property sector. Yet by trying to explain the concrete situation supposedly lying behind the image more fully, or by illustrating or decorating the moment of sketched action with words or lines, one would barely be doing justice to the understanding of the image. Fleeting associations of real experiences or memories of communicated events (whether through the media, through film, the spoken word) are enough and at the same time the maximum of what is possible or bearable in terms of interpretation. Holub’s drawings prompt a recognition of images, moments of action, individual gestures, without the viewer having experienced the specific situation, the basis for the image, or even a precise representation of it. At the same time, the images create an opportunity to reassess habitual ways of seeing, familiar images, to open up new layers of meaning. What Holub’s work tells us is that there are no innocent images. The images are already in us. We are the images.

Window screens on the world

A second drawing by Holub, entitled “Leisure Energy”, evokes the mood of a weekend spent at a lake: a few parked cars can be seen on the left of the picture, next to them canopies with people underneath, and next to them two people sitting on blankets. In front: a small bus, a jeep with a cargo rack, another vehicle whose rear is all that is in view, as well as a boat trailer, and to the right (in the middle of the picture) two small motor boats, one of them with people on board. On the right of the picture there are people in casual wear, between them signs, in the foreground a child. Everyone’s gaze is turned leftwards, obviously because of the sun, since some of the people in the background are shielding their eyes with their hands. One man, who is standing on the far right of the scene, is holding something that looks like a remote control. The proportions on the right hand side of the image are significantly larger than those on the left. It looks as if the scenery on the left were the toy-world as seen from the right. This impression is heightened by the fact that in both scenarios, the “floor” is missing, the ground. Lastly, in the bottom left, there is a strange element. It has the form and the darkened colour of the window screen of a top-class American SUV. Drawn onto it in white lines are the torso and the arms of a man dressed in a casual jacket, and this male figure is also holding a remote control in his hands. The man has no head, no face: he is unrecognizable. On the darkened window of the SUV he appears as the headless driving subject of a narrative action that keeps itself to itself.

The heavy, curved glass is at once object, ground and narrative fragment from another layer of reality. It is part of the drawing, part of the story and at the same time something that indicates towards the space outside, to the real site of events, to life on the streets. Holub’s works are puzzles that bracket the interior space of the narrative within the exterior space of life, always keeping in mind that puzzles are based on the interplay of fragments; that the narrative can never be linear if it is to do justice to that which appears to us as reality.

Urban space, urban periphery

Who does public space belong to? Who determines what actions are allowed and welcomed within it, and what actions are declared illegitimate and criminalized? In Disrupting the pleasure of relaxation, it looks as though somebody has built a tool in order to obtain figs from a tree that does not stand within his private property. The drawing shows the forbidden act of fig-theft. The body language of the “robber”, whose head is bent low, his hands holding the pole tightly, suddenly evokes images of a sniper, as we know these from films or news programmes. Scenes of illegal acts merge into one another, although the image of the crime is the first to develop in the mind.

In Los Angeles, says the artist, there is barely any public space that does not serve a specific purpose, where one can pass the time without having to consume. However people are inventive and look for places in everyday appropriations. Everywhere there are fly-posters for “yard sales”, small flea markets in the gaps in the urban space that invite you to come and rummage around, to take part in an informal exchange, to while away time free of charge. “Places to play and listen”, one might say, in allusion to Michel de Certeau. The urban space becomes an actor, an active subject and a protagonist in the action. In the work This Time on the Other Side of the Street, Next Time Us, a similar situation is represented: a photo and a drawing of one of these “yard sales”, which overlay each other like different transparent layers of an open story that unites ideal and real space. The image itself, however, reproduces only the atmosphere that underlies the situation, not the content.

But an image, a story, can also arise within a real action, in the same way that one can walk through the city as if one were following a story. The artist invites us on suburban walks around Aspern, a district on the periphery of Vienna, where a city of the future, Aspern Lake City, is planned, where men in suits very likely shake hands and pat one another on the back; on these walks, various people will make contributions on and around the concept of the “periphery” and the potential of the unplanned. By the end of June 2010, billboards will be placed in front of the local council building in Aspern bringing together a selection of Holub’s painting book images in a dense montage. The scenes depicted are re-organized with respect to the potential unplanned discoveries and opportunities for Aspern. Relations of size vary and the individual situations partly overlap one another, close-ups of figures and gestures are linked to supposedly neutral views across an entire scenery. The mobile billboard walls are erected in such a way that they form a triangle. In other words, you have to walk around them in order to see all the details one after the other. A kaleidoscope of life emerges in a kind of three-dimensional collage from which it becomes practically impossible to escape.

The billboards will be supplemented by a new drawing that Barbara Holub will produce for Aspern on the basis of photographs of residents. A book with a collection of the drawings in the form of a painting book will be presented in November (Verlag für Moderne Kunst Nürnberg). The book will be accompanied by a CD of the suburban walks first performed as a production for Ö1 Kunstradio on 14 November 2010.