A trace of Russia at the heart of Austria

The political cover-up – a lethal mixture of disinformation, false arrests, smear campaigns and mysterious deaths – is a well-honed means of suppression. When communities of German-speaking origin spoke out about Soviet regulation causing starvation across Ukraine during the Second World War, human rights advocate, Ewald Ammende, also suffered the consequences.

In the early 1930s, as the world struggled with the Great Depression, the USSR was undergoing extensive industrialization. Before the first Five Year Plan (1928-1932) had even been completed, the Soviet authorities were proclaiming their triumphs with the slogan: ‘A slump for the capitalists, growth for the Soviets!’ The transformation of a backward agrarian country into an industrial economy could never have occurred that quickly without skilled help, recruited largely from Germany and Austria as well as the UK. Some experts moved to the USSR because they couldn’t get work at home; the Soviet authorities promised a combination of high wages and job security. A number of these specialists were also active supporters of the Communist Party. However, in the mid-1930s, the authorities in the Soviet Union set about disposing of professionals deemed surplus to requirements. Court cases were launched against foreigners accused of spying.

The success of Soviet industrialization, and the opportunities it opened for the world economy, obscured the other process taking place in tandem: forced collectivization. Grain was a political commodity. First, it was needed to ensure that the increasingly numerous working class had enough to eat; after all, the workers represented the underpinning of the Soviet system. Second, Western currency – essential for continuing industrialization – flowed into the economy through the global sale of cheaply priced Soviet grain. The more grain there was to sell, the more Western currency poured in. The greater the flow of currency, the better the effects of industrialization and, consequently, the greater the number of workers – which also meant fewer peasants, which the Soviet authorities regarded as hostile.

The region that troubled Stalin most was Ukraine, where local peasant farmers represented a natural base for a potential uprising. Stalin viewed Soviet Ukraine as the workers’ ‘breadbasket’, but he also wanted it to become a secure buffer zone for future war. The famine that emerged from collectivization, and from the expropriation of grain from southern regions of the USSR, was the result of planned policy. The genocide it unleashed in Ukraine became known as Holodomor. Starvation in this region was at its worst in 1932-1933 but, in the countryside, people were dying of hunger both before and after this, until at least 1934. Authorities blockaded the affected areas, and the internal borders of Soviet Ukraine were closed to ensure that the rural population couldn’t escape.

Despite censorship and jamming, news of hunger in Ukraine, the Volga steppes and Kuban leaked out via devastated refugees,1 through private letters and, not least, by way of foreign press reporting. Even though non-Soviet journalists were forbidden to travel in the provinces and had their reports suppressed, some succeeded in smuggling material through to their editors in diplomatic bags. However, the approach that editorial offices took is a different matter. The famine was a sensitive issue at a time when most European countries were seeking to improve relations with the Soviet Union.

In their press reports, few correspondents differentiated between famine in the USSR as a whole and famine in Soviet Ukraine. Reference was generally made to ‘southern regions of Russia’ (Ukraine’s official name during Russian Empire times), partly because few readers were familiar with the region and partly from an aversion to ‘Ukrainian separatism’, which was widely viewed as a blight not just in Moscow but outside the USSR as well. It wasn’t until March 1933 that reports in the Manchester Guardian by Gareth Jones and Malcolm Muggeridge (who published under a pseudonym) finally drew attention to the scale of the disaster and to the region most affected by it: Soviet Ukraine.

German newspapers wrote about hunger in Russia with a particular focus on the Volga steppes, where there were large German settlements. There was also some reporting on south-eastern Ukraine, an area with a smaller German colonial presence. The organization Brüder in Not initiated relief effort for Germans in the USSR, together with the German Red Cross, and subsequently began to document evidence of starvation.2 In June 1933 an exhibition organized to publicize the famine and collect funds to support victims provoked uproar in the Soviet press; by supporting this event, Adolf Hitler was said to be diverting attention away from his own policies. Following protests from Soviet diplomatic circles, the exhibition was closed after just ten days and a demonstration to show solidarity with victims of the famine, which had been planned for early July, was called off.

The USSR consistently denied the existence of a food crisis, using various forms of strategic deception. Soviet authorities forced collective farm workers of German origin to write group letters to the Soviet press not only negating the fact that they were starving but also accusing Germany of spreading propaganda about the famine. Communications from the authorities also denied that the farmers were starving, praising Soviet regulations for creating prosperity instead: specially commissioned reports were sent to the Western press and visits were made by celebrities to fake ‘Potemkin’ villages. The authorities also orchestrated news events as weapons in its disinformation war to deliberately distract the Western press from the famine. British engineers under contract in the USSR, for example, were arrested and accused of spying; therefore, public attention refocused on the relevant show trial and on efforts by the British government to free its citizens. Access to the trial was granted in exchange for the press remaining silent about the famine. Reporting in Britain on the famine was thereby effectively muzzled. Later, when the Soviet authorities finally admitted that there were ‘certain difficulties with food supplies’, they continued to deny that there was any difference between hunger on the territory of Russia or Kazakhstan, and famine in Ukraine. Evidence was produced to show that all regions were equally affected.

The Soviet propaganda machine shaped its narrative around the doctrine that the Ukrainian famine was a Nazi invention. The argument that starvation in the region was manmade and had been caused by a genocidal policy pursued by the Soviet authorities was said to prove that Ukrainian nationalists were conspiring with the Nazis. Russia viewed (and still views) anyone writing about the Holodomor as a proponent of Nazism, and those who point to the difference between hunger on Soviet territory caused by collectivization, on the one hand, and the Holodomor as a genocidal policy directed against the Ukrainian people on the other, are still ferociously attacked. It is not widely known, however, that people who spoke out about this in the 1930s were silenced by smear campaigns or even by ‘physical elimination’ (in NKVD-speak) – in other words, they were assassinated.

Appeals from a metropolitan and a cardinal

Holodomor Remembrance Day, Kyiv. Image via Wikimedia Commons

In the summer of 1933, the Greek Catholic Archbishop of Lwów, Metropolitan Andrzej Szeptycki, raised the issue of the famine with newly appointed Cardinal Theodor Innitzer. Earlier, on 24 July 1933, Szeptycki had published a pastoral letter entitled ‘The death throes of Ukraine’, which called on believers to give aid to the people starving in the region, and on Christians to protest against the genocidal policy of the USSR. A few days later, the letter was republished in Reichspost, the largest Catholic newspaper in Austria closely connected to government circles.

Responding to Metropolitan Szeptycki’s call, the front page of Reichspost on 20 August carried an appeal from Cardinal Innitzer to organize urgent international aid for Ukraine. This was picked up by news agencies worldwide, and the appeal subsequently appeared in leading international newspapers from The Times to The New York Times. It reached readers in the UK, France, Germany, Italy and the US. The Soviet authorities reacted in a way that was entirely predictable: once again, facts about the famine were denied; representatives of foreign relief organizations were refused access; and the offer of international aid was rejected out of hand. The Soviet government spokesman offered a brusque response: ‘Thankfully,’ he said, ‘here we have neither famines nor cardinals.’

Innitzer decided to set up a relief committee formed in such a way that it couldn’t provoke allegations of political meddling or proselytization. The membership was to be international and interfaith. It is unclear whether the cardinal was acting on instructions from the Vatican, but it seems unlikely that he would have undertaken the project without the full knowledge and agreement of the Pope. The Interfaith and International Committee to Help the Territories of the Soviet Union Suffering from Hunger was established in the autumn of 1933. Ewald Ammende was appointed as honorary secretary.

Ammende was well known for his boundless energy. As General Secretary of the Congress of European Nationalities (ENK), he had promoted cultural autonomy for ethnic minorities and encouraged close cooperation with the League of Nations to assure minority groups the broadest possible rights. He maintained close contact with officials from the League, and with leaders of national minorities from Catalonia to Livonia. He was widely published by the German language press throughout Europe, from Reichspost in Austria to Neue Zürcher Zeitung in Switzerland. When the ENK head office moved from Switzerland to Vienna in 1930, Ammende settled there.

Between 1921 and 1923, Ammende had taken part in an international relief effort to help the starving in Russia. He was no stranger to famine: in 1930 he argued that catastrophic food shortages, such as those that had occurred due to Bolshevik policies and militant communism, could return. As general secretary to the ENK, he began to issue warnings about the possible consequences of Soviet collectivization. He was critical of the German authorities’ refusal to provide aid to Germans living in the USSR, and no less critical of the Soviet government. But Ammende was not a politician. He was an activist on behalf of a national minority. With his knowledge, experience and range of international contacts, he seemed the ideal candidate for the role of honorary secretary in Innitzer’s committee.

In spring 1933 the Estonian German-language newspaper Revalsche Zeitung, with which Ammende cooperated, began to publish alarming reports about famine in southern Ukraine and the Volga region. Despite the Soviet authorities’ persecution of rich peasant farmers or kulaks, the region remained widely populated by these settlers of German origin. After the fall of the Tsar, Latvian and Estonian Germans had continued to maintain links with their compatriots outside the USSR – as far as changed circumstances and the Joint State Political Directorate (OGPU) perlustration of foreign correspondence allowed.

Before the Bolshevik Revolution, the German minority had been one of the best organized national communities in the Russian Empire. It was unsurprising, therefore, when, alongside Galician Ukrainians, the Baltic German minority was the first to raise alarm when their compatriots in the Volga region cried out for help. Unlike the Ukrainian people who had no state or international organization outside the USSR to speak on their behalf, German colonists enjoyed the support of the German state – theoretically speaking, at least.

In practice, however, Vice-Chancellor Von-Papen and the German diplomatic corps continued to act in accordance with the Rapallo Treaty until January 1934. Meanwhile, aid was provided by the Catholic diocese, by Protestant groups, by a particularly generous community of Mennonites living in the US, and by the Brüder in Not organization. In early March 1933, Hitler – by then the German Chancellor – started using reports about the famine for his own purposes, launching an attack on Soviet policy in one of his speeches. It was no more than an exercise in rhetoric, but what Hitler said didn’t escape the attention of the Soviet diplomatic representative, who protested. The People’s Commissar for Foreign Affairs, Maxim Litvinov, also summoned the German ambassador for a formal dressing down. As a result, a major demonstration against the famine in Soviet Ukraine was called off in Berlin.

At the end of June 1933, Reichspost published a letter from Ammende, and a couple of weeks later his letter on famine, which used ‘the horsemen of the Apocalypse riding through Russia’ as its metaphor.3 Even though the article discussed Ukraine, the Volga Region steppes and the Northern Caucasus, interestingly the editors chose to use the traditional term ‘Russia’. Ammende put the famine down to collectivization and other Soviet government policies implemented at huge cost to peasant farmers who supplied food for workers. He proposed that a relief effort, along the lines of the 1921 campaign, should be organized for those affected by the famine. It would be led by the Red Cross and remain under the control of the Soviet authorities.

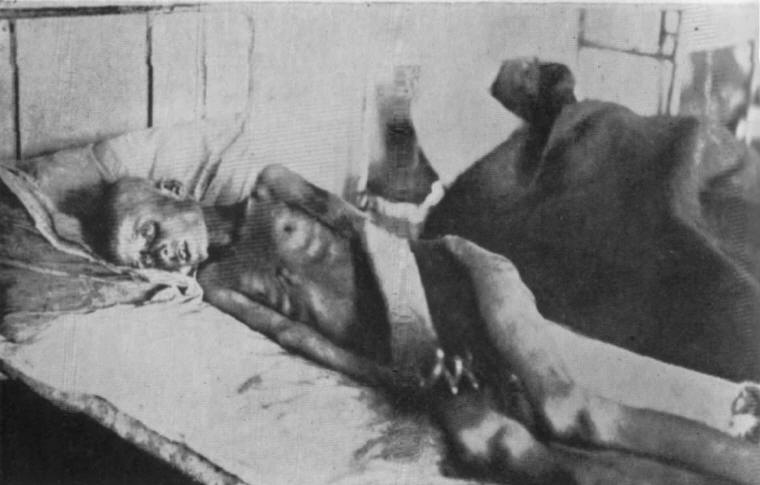

1920s Russian famine victim, Volga region. Photograph brought back from Russia by Norwegian Fridtjof Nansen. Image via Wikimedia Commons

The article received an immediate reaction in the pages of Rote Fahne4 and in the Soviet press. On 20 July 1933, under the headline ‘Austrian newspaper publishes anti-Soviet libel’, the Soviet news agency TASS wrote that:

the methods of black fascists in the Austrian Christian Social Party and those of the brown fascists of the National Socialist German Workers’ Party are two of a kind.

The Soviet newspaper Izvestiya followed suit. It called Ammende’s article ‘a provocative story invented by German National-Socialists’ and dismissed Austria as ‘a country of hungry beggars living on handouts from abroad’.5 The message to the Austrian authorities was clear: Ammende was being openly denounced. It was also a signal for the Russian security services to act.

Vienna received news of the official Soviet reaction to the Reichspost article from the Austrian envoy in Moscow, Heinrich Pacher, who repudiated Ammende’s argument and his prediction of more deaths from starvation in the winter of 1933-1934. Pacher wrote that there was no real reason to fear the coming year would bring more famine.6 He also added that the situation in Ukraine was considerably better than expected. Exactly why Pacher was peddling the Soviet propaganda line about a rich harvest in the summer of 1933, and thereby passing disinformation to the Austrian authorities, is hard to fathom.

Towards the end of July, the Lviv-based Ukrainian newspaper Dilo published another article by Ammende entitled ‘Famine in Ukraine’, which, the paper said, had been written specifically for them. It appeared on the front page beside a communique about the formation of the Ukrainian Civic Committee to Help the Hungry in Ukraine. In the article, Ammende first put forward his thesis that hunger was a weapon being used not just against Ukrainian peasants but also against the feelings of loyalty Ukrainian communists harboured towards their own people:

The open and ruthless exploitation of Ukraine, with no matching equivalent at the Moscow end, is causing discontent in the ranks of even the most ideologically committed Ukrainian communists and finally leads to open hostility, as was clearly seen at the meeting of the Central Committee in Moscow, where the Ukrainian delegation was simply tied up and handed over to the GPO.7

From the late 1920s onwards, Ammende was in close contact with Ukrainian sources from Galicia (then a region of Poland). He drew his information not only from German and British newspapers – which he knew well – but also from Galician Ukrainians. Although he could clearly distinguish between hunger in Soviet Russia and famine in Soviet Ukraine, his perception was coloured by his Baltic German origins and his experience as a citizen of the Russian Empire.

The Soviet authorities repeatedly denied the truth of foreign press reports and didn’t stop there. They initiated a counteroffensive. In summer 1933 news from the USSR carried by foreign newspapers, including the Austrian press, was dominated not by the eyewitness reports that occasionally filtered through to the media, nor by calls from Ukrainian bishops or indeed by Cardinal Innitzer, but by a visit to the Soviet Union from the former French prime minister and leader of the radical socialist party Edouard Herriot. His trip took place at the end of August and was reported in considerable detail. It was a ‘private’ visit made during a short break between high-level official duties at home, but the Soviet authorities received him with all honours due a head of state.

When Herriot returned to France, he announced urbi et orbi (to the city and to all the world) that Ukraine was flourishing and literally flowing with milk and honey. He categorically denied the veracity of any reports about famine. This story, from an influential public figure, whom the Soviet authorities chose to use as their prime witness, was designed to persuade world public opinion that there was no hunger in the USSR, and especially in Ukraine, and that the food crisis was a story devised by anti-Soviet, enemy propaganda.

United we stand

One of the few international bodies in a position to examine reports about the fate of the Ukrainian people was the aforementioned Congress of European Nationalities (ENK), led by president Josip Vilfan and administered by its general secretary, Ewald Ammende. Whereas annual ENK meetings were commonly forums open to discussing the Ukrainian people’s unenviable situation in Poland, Ukrainian representatives from Galicia and Romania held back from raising concerns relating to their own minority communities in the ninth meeting held in the Bundeshaus, Bern, 16-19 September 1933. They conceded instead that the famine in the USSR was the most important issue to be addressed at the gathering, not just from the Ukrainian point of view but also from that of all minorities represented.

While Vilfan declared that the question of minorities living on Soviet territory was outside the ENK’s brief, Ammende expressed his support for the topic’s inclusion on the agenda. Knowing that Vilfan was a Russophile, he suggested to the ENK vice-president, Professor Mikhail Kurtschinsky, who was an Estonian Russian, that the famine should be raised at the inaugural session. His address was followed by a speech from Milena Rudnycka, who accused the Soviet authorities of imperialist policies and the intent to wipe the Ukrainian people out of existence. Her remarks were widely reported in the Austrian press.8

Milena Rudnycka made her statement just two weeks after fascist Italy signed its Treaty of Friendship, Non-Aggression and Neutrality with the USSR. Earlier, during a personal meeting with Mussolini, she had attempted to persuade him to intervene on behalf of the millions affected by hunger but failed. Mussolini was conducting negotiations with Stalin at the time, in spite of the reports he was receiving from his diplomats about the Great Famine in Ukraine.

Following Rudnycka’s statement, the ENK passed a resolution calling on global public opinion to initiate a relief effort for victims of the famine. This appears to have happened counter to Vilfan’s wishes as a result of the backing representatives of German minorities gave to the resolution. While their support appeared natural enough (bearing in mind the publicity German language newspapers were giving the situation faced by their compatriots in the USSR), in the eyes of the public, this expression of solidarity was seen as nothing short of incriminating. It was interpreted by Soviets as evidence of manoeuvrings by the German propaganda machine and proof that Ukrainians were being used as its instrument.

The resolution was forwarded to the secretariat of the League of Nations, which was to meet the following week. At this gathering, Rudnycka and Ammende found themselves engaged in their next battle, amounting to another element of this story too involved to unfold here. Suffice to say, since the USSR was not a member of the League at the time, the matter was passed to the Red Cross. And, predictably enough, the Soviet authorities refused to accept any offer of help from the Red Cross, on the grounds that the famine was ‘an invention of German propaganda’. They did however offer a considerable aid package to victims of an earthquake and a famine in India. Within a year, the USSR was admitted to membership of the League of Nations. The wheel had come full circle.

A month after the ENK meeting on 16 October 1933, a gathering of representatives from various religious groups took place in the Archbishop’s Palace in Vienna. It was attended by Catholics, Greek Catholics, Orthodox, Protestants and Jews, and led to the establishment of the Interfaith and International Committee to Help the Territories of the Soviet Union Suffering from Hunger,9 with Cardinal Innitzer at its head. The gathering was unprecedented and received wide press coverage. Committee members were undoubtedly conscious that they were likely to meet with a hostile response from the Soviet authorities, but they were religiously committed and felt it was their responsibility to help. They also understood that the scale of the food crisis meant that provision of aid was beyond the scope of individual organizations or groups. A memorandum written by Ammende underpinned the committee’s work. It emphasized the apolitical, humanitarian aspect of the relief offered and how it must be supranational, with no single religious affiliation, given to all victims of the food crisis. It was hoped this would serve as evidence that Soviet statements suggesting all calls for aid were steered from Berlin were false.

Committee members also hoped that help for victims of the famine would be handed out by aid organizations, even though the Soviet authorities would remain in charge of its distribution. The USSR didn’t allow this, however. Aid continued to be given out solely by Torgsin shops which sold food for hard currency. The money that flowed in through this network was unlikely to help many people, but the system did offer the Soviet government an opportunity to kill two birds with one stone: first, it brought in more foreign currency (in addition to that which came from the sale of cheap grain); second, it provided the authorities with addresses of people with contacts abroad. It took less than a year for this data to be put into practical use: nearly all recipients of aid from outside the USSR were arrested and charged with acting as foreign agents.

In mid-December 1933, Cardinal Innitzer convened a conference for representatives of all religious denominations and organizations engaged in helping victims of the famine. It was attended by members of numerous Ukrainian committees, alongside delegates from German, Jewish, Russian, Greek, Serbian, Swiss and British aid organizations, and spokespeople for various religious groupings. Details of the proceedings and biographical information about the participants were published in a 64-page brochure entitled Hungersnot! (Famine!). The booklet also included material from the Austrian, British and French press, as well as letters from regions affected by food shortages, especially Ukraine. The event was opened by the cardinal who called upon state leaders to reconsider the advisability of signing new contracts with the USSR. The delegates then issued an appeal to public opinion worldwide.10

Nec Hercules contra plures11

The Viennese conference failed to produce the expected results. Western countries didn’t introduce changes to their foreign policies. World leaders and international organizations, keen to avoid antagonizing the USSR, made efforts to appease Stalin, much in the same way that – five years on, in 1938 – they would seek to appease Hitler in Munich. In November 1933 the US established diplomatic relations with the Soviet Union. While this was an event of key importance, equally, between 1932 and 1934, many European countries also made agreements with the USSR, including Italy, France and Poland.

In September 1934, just a year after the Soviet authorities had condemned millions to death by starvation, the USSR was invited to join the League of Nations. This happened in the context of the aforementioned policy of appeasement, and just as the Third Reich left the organization. The impression was that of an exchange. Contrary to widespread perception, the Soviet accession to the League was not just the result of anxieties which Hitler’s rise to power had provoked – there were political and economic causes as well. European states and the US were making great efforts to build good relations with the USSR. There were fears of severe losses for business and state guarantees were offered to support supposedly lucrative contracts with the Soviet Union. The global economy had not yet recovered from the Great Depression.

The downturn remained especially harsh in Austria which was affected by not only the global economic crisis but also political clashes and a civil war. In addition, German government sanctions crippled the Austrian tourist industry, which represented a significant part of a state budget already damaged by the slump. Desperate to maintain its independence from Germany, Austria entered into brief alliance with Mussolini’s Italy. Like so many others, the Austrian authorities looked hopefully in the direction of the USSR. Economic concerns and anxieties about aggravating Austro-Soviet relations prevailed over ideological differences. Austria was torn by severe internal divisions. On the one hand, there were communist activists gazing into the mirage of a proverbial ‘’, promoting Soviet interests, and zealously carrying out Moscow’s directives. On the other, there were Hitler’s supporters, seeking union with the Third Reich. 1934 brought a political earthquake. It began with the Februaraufstand (the February Uprising), carried out with the participation of the Republikanischer Schutzbund – a paramilitary organization supported by the Social Democrats. Next, there was the assassination of Engelbert Dollfuss and a failed coup.

Cardinal Innitzer’s activities were a thorn in the side of the Soviet authorities – but they were a nuisance for others as well. The Austrian government was aware that it couldn’t afford to worsen its relations with the USSR. Consequently, it decided to neutralize Innitzer’s endeavours as head of the Interfaith and International Committee. The most effective means of achieving this was to undermine the cardinal’s trust in his honorary secretary – for, like the USSR, Austria now viewed Ammende as ‘an agent acting to achieve goals set by Berlin’.12 But how was the Austrian government to encourage the cardinal to call an end to his activities without undermining his authority? He was, after all, a pillar of the Austrian state.

The simplest route lay though Rome, where Innitzer travelled towards the end of October 1933, soon after the first meeting of his committee at the Archbishops’ Palace in Vienna. He was presumably planning to give a report on the Interfaith and International Committee’s actions to the Pope.13 Pius XI was sympathetic to the plight of victims of the famine but anxious to avoid any engagement in the ‘canonical territory’ of the Russian Orthodox Church for fear of provoking repression against Roman Catholics. During the cardinal’s visit, and on the instructions of Chancellor Engelbert Dollfuss, the leader of the Austrian mission held a meeting with Innitzer and, in the course of the conversation, issued a warning about Ammende. He indicated that the honorary secretary to the committee had links with the Nazis and was an old schoolfriend of Alfred Rosenberg’s. The imminent visit of Joseph Goebbels to Rome, he suggested, spoke for itself. The diplomat instructed the cardinal not to issue any letter of recommendation to Ammende, as he prepared a trip to America to raise funds for the famine relief efforts. Nor was the cardinal to solicit any kind of letter of introduction for his secretary from the Pope.14 Reports of this conversation, which filtered back to the cardinal’s office, indicate that he emphasized the considerable global interest that the aid project was generating, whilst promising to not give the Soviets any excuse to attack the relief effort. He also agreed not to support his honorary secretary, who had been the linchpin of the committee. Ammende’s official role was thereby nullified.

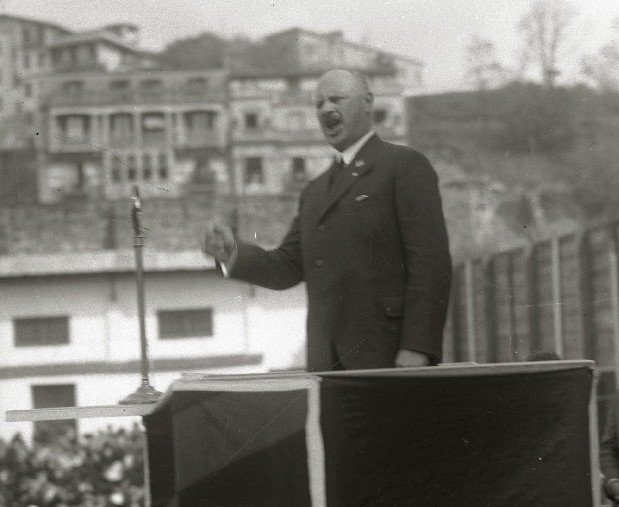

Ewald Ammende, old Maitea football field, Atotxa, Spain, 1933. Image by Fondo Marín. Pascual Marín, managed by Kutxa Fototeka, via Wikimedia Commons

Ammende set off for the US with no letters of recommendation but with unique photographic documentation that had reached the committee at the beginning of 1934, depicting the effects of the famine the previous year in Ukraine’s then capital, Kharkiv. He began his trip by stopping off in the UK, visiting London and Edinburgh in May 1934. He spoke with experts on Eastern Europe and a wide range of parliamentarians, both privately and officially. At the House of Commons, he met members of the coalition government’s Russia Committee, alongside specially invited guests representing various aid organizations. Everywhere, he was insistent that religious groups, rather than politicians, should advocate on behalf of victims of the famine and publicize the need for aid. It would be inappropriate to attribute the Archbishop of Canterbury’s appeal to parliament at the end of July 1934 directly to Ammende’s efforts, but his plea was nevertheless made soon after the visit had taken place.

From the UK, Ammende travelled to North America. On his arrival at the end of June, he had a letter published in The New York Times15 and, in July, several interviews with him appeared in the American press.16 Local newspapers also reported on the visits he made to different communities. On 4 August – a day before his return to Austria – Ammende argued in a New York Times interview that Soviet reporting about the 1934 harvest was as untrue as that about the harvest in 1933.17 He referred to the General Secretary of the Communist Party of Ukraine Stanislav Kosior’s statement, made in June 1934, about the need to mobilize the military to confiscate Ukrainian crops, so they could be sold abroad – a plan intended to generate some badly needed income for the USSR. He remarked that, since the Soviet authorities were falling back on methods of civilian control such as this, the threat of starvation in the coming year must be very real. The Soviet ambassador intervened. Ammende’s subsequent trip to Canada gave rise to a run of petitions from different religious and national groups to Prime Minister R.B. Bennett, calling for the Canadian representative to the League of Nations to insist that the Soviet Union be admitted into the League only on condition that it agreed to accept aid for sectors of its population affected by famine.

Nevertheless, in the summer of 1934, it became evident that the USSR would be joining the League irrespective of all objections. There were protests from Ukrainian groups and from international organizations, including the ENK, which made efforts – until the hammer fell in September – to show that a country that systemically infringes the rights of minorities should not be admitted. By way of final effort, the tenth meeting of the ENK in Bern adopted a resolution stating that the USSR’s future membership of the League of Nations should be linked to famine relief on its territory.18 Previously the League had done nothing on the grounds that the Soviet Union was not then a member. The ENK resolution was passed to the secretariat of the League, along with other materials, but despite this, in September 1934, the USSR was unconditionally admitted. The repressions against minorities in the Soviet Union were treated as an acceptable, necessary evil.

One organization that nevertheless protested against the admission of the USSR into the League of Nations was the Anti-Comintern – an agency established in autumn 1933, subordinate to the propaganda ministry of the Third Reich. As an activist working on behalf of German minorities, Ammende had kept up contacts with Berlin and, no doubt, had seen Anti-Comintern publications. He also very probably knew about its activities – and it may well have been this that led to his eventual downfall. Disappointment with the failure of the League of Nations to act urged him into closer contact with the Anti-Comintern.

Kompromat

After the murder of Dollfuss and the failed coup, the Austrian authorities launched an internal operation to hunt down Hitler’s supporters. Some were real, others imagined. Ammende had been under observation by the Austrian security police for some time: his hyperactivity and connections with Berlin were causing concern. But to avoid unnecessary publicity, he was allowed to remain in the country. Nobody knows who took the decision to resolve things differently, or when. There are indications that the Austrian authorities were ‘assisted’ by Soviet agencies. A pretext for discreditation duly surfaced, as did a prime witness.

In the summer of 1935, Karl Brtnicky, an unemployed man from Vienna with a criminal record, reported to the police that he had successfully blackmailed Ammende. He maintained that he had done so on the grounds that Ammende was actively gay, which was a punishable offence in Austria at the time. Accordingly, the police took action against not the blackmailer but Ammende. The investigation revealed that, after Brtnicky had forced his way into Ammende’s apartment demanding money and clothes in exchange for silence about the ENK general secretary’s alleged homosexuality, Ammende made a phone call to his lawyer. He was advised that informing the police and taking the matter to court was likely to make a public issue of the story. This was something Ammende was anxious to avoid: he had an image to think about. On the lawyer’s recommendation, he gave Brtnicky a small sum of money and some items of clothing in the hope that the event was an isolated incident and not part of some kind of plot to discredit him. Following this, Ammende spent several weeks under medical care.

Most probably, those who orchestrated Brtnicky’s actions had initially hoped that blackmail would produce a more spectacular effect. Since it didn’t, Brtnicky had to go to the police, despite, therefore, informing on himself. Consequently, Ammende’s alleged homosexuality became a public issue, just as originally intended. Josip Wilfan insisted that, henceforth, any speeches his general secretary made should be delivered only in a personal capacity. Ammende, previously the organization’s spiritus movens (its driving force), found himself side-lined.

The case lasted several months. Brtnicky repeatedly changed his story and feigned illness. From his point of view, things had evidently taken an unexpected turn. In November 1935 Ammende’s legal status changed: he had started out as the accused; then he was the victim. The proceedings began afresh and the trial was scheduled for the beginning of 1936. In his testimony, Ammende tried to explain that Brtnicky had probably been incited to act by an outside source. It is hard to glean from the minutes if he was referring to the Soviet authorities. At the end of December 1935, Ammende left Vienna, as there was no longer any obligation for him to wait until after the trial was completed. But he never returned. Nor was he ever rehabilitated. And Brtnicky was soon released.

Ammende had to contend with blackmail, and the legal proceedings that followed, just as he was writing his book Muss Russland hungern? (English title: Human Life in Russia). A year earlier, in 1934, as the ENK’s general secretary, he had liaised on the publication of a brochure entitled Russland wie es wirklich ist (Russia as it really is), issued by the Patriotic Front. It contained photographic evidence of the famine. The author, Alexander Wienerberger, preferred to remain anonymous for his own safety, but Ammende had made use of the photographs during his transatlantic trip in 1934 and, later, also included them in his book.

The Soviet Embassy protested against the brochure, demanded that it be withdrawn, and immediately linked it to Cardinal Innitzer’s committee. Ammende’s Human Life in Russia received similar treatment. There can be little doubt that the Soviet secret services were monitoring the two publications and devising ways to counteract their influence. The most tried and tested means of achieving this was to discredit and thereby silence an adversary or, if that should fail, to physically eliminate them.

In September 1935, on his return from the eleventh ENK meeting in Geneva, Ammende wrote to Chancellor Schuschnigg requesting a response to the question whether he, and the ENK, still enjoyed the trust of the Austrian authorities, or if the time had come for them to move to another country. The letter was despatched in the wake of attacks on Ammende in the Austrian press and following the initiation of legal proceedings against him. It was filed away in a dossier of government documentation with the comment that the author was attempting to make use of high-level patronage to reach the chancellor.

Ammende was not sent into exile, but the publicity surrounding his book in the autumn of 1935 displeased the authorities. Soviet intervention generated feverish efforts to find a solution to the problem. In early November, the editor of Reichspost was admonished for publishing a positive review of Human Life in Russia and asked to curtail any further discussion of its contents. Nevertheless, the book was not withdrawn from circulation, even though official censors were unhappy about its presence on the market and about its promotion in Reichspost. It soon transpired, cannily enough, that the entire edition had been removed from circulation in Austrian territory. Reported comments from the chancellor’s office suggest that the news was greeted with considerable relief.19

The reason why the book generated such violent displeasure in Soviet circles is clear. But why was it that the Austrian authorities also came to regard it as so damaging? There were fears of repercussions from the Soviet end, no doubt, but could the message of the book be construed as a tool of Nazi propaganda? A careful reading would suggest the opposite.

Whereas Ammende’s earlier publications had focused on analysing the causes and effects of the famine, Human Life in Russia also explored Soviet state policy towards foreign citizens and in particular the authorities’ campaign against the Ukrainian people and their battle for survival. ‘Moscow now has a direct interest in the destruction of a large part of the generation now living in the Ukraine and in other autonomous districts’, wrote Ammende.20 He discussed the means by which the USSR propagated its supposed successes and the ways in which the party line affected global public opinion but didn’t confine himself to criticizing Soviet policy. He also accused world leaders of sacrificing entire nations and peoples at the altar of good relations with the USSR:21 ‘The authorities in Berlin, Helsingfors, Warsaw and Riga have resigned themselves to the destruction of their kinsmen in the Soviet Union.’22 Ammende was cautious enough to avoid the mention of just one country: Austria. Instead, he saved his most bitter critical remarks for the League of Nations. The book ends with a question:

Will [the countries in the League] exert themselves to make the Soviet government respect the principles which it adopted when it joined the League of Nations – by allowing, for example, a commission to visit Russia and investigate the real state of affairs in the agrarian districts and in all those places where exiled persons and prisoners are employed in forced labour for the State?

The answer to this question is, in my opinion, of quite decisive importance: on it may well hang the fate not only of the people in the Soviet State but of our Western civilization.23

Ammende’s question may appear purely rhetorical today, because we have received the answer. Yet it remains relevant.

It is evident that, as Ammende set out on his next trip in December 1935, he felt that disaster was looming, both in terms of aid for victims of the famine and as regards any systemic improvement of conditions for national minorities. He was fully persuaded that the League of Nations had proven a fiasco. It was clear to him that the purpose of Soviet policy was the annihilation of all non-Russian peoples living in the European part of the USSR. On this occasion, he was travelling not as the general secretary of the ENK but as a private individual, discretely supported by the German diplomatic corps. He was planning to look into the activities of the Comintern and of Soviet envoys in South America and Asia – something of which he knew a fair amount already. But he wanted to find out more, and to share it. During the trip, he brushed shoulders with a number of Soviet envoys. He died suddenly in Peking. The official cause given was circulatory shock.

Soviet influence was undeniably strong in China. Eight months earlier, the journalist Gareth Jones had also died there. His reporting on the famine in Soviet Ukraine had induced the Soviet authorities to reach for the heavy artillery – in the form of Walter Duranty, The New York Times’ Moscow correspondent, who denied the existence of any famine and had accused Jones of lying.

The smear campaign against Ammende bears striking similarities to another operation conducted by the Soviet secret services: the discreditation of Archduke Wilhelm Habsburg who was publicly ‘exposed’ as a homosexual and a swindler. The story killed two birds with one stone: it frustrated attempts to restore the Habsburg monarchy and ruined the reputation of a claimant to the throne of Ukraine. In Ammende’s case, the designated goal was achieved only in part. He was compromised in the eyes of his closest colleagues in the ENK but continued to present a threat to the activities of Soviet foreign intelligence. After his death in April 1936, both the ENK and the Interfaith and International Committee followed suit: the two organizations died of natural causes. The ENK had been proving a headache for the authorities of numerous countries and the committee presented a problem not just for the USSR but for other states as well.

The same year also saw the publication in the US of the English language version of Human Life in Russia, with an introduction by the well-known British politician and philanthropist Lord Willoughby Dickinson. It ended with the words:

Dr Ammende has died, a victim to his own unceasing activity. He has died and lived for others, and the world is the richer by the example of his life and of his death.24

Epilogue

The Austrian authorities and the public were not short of information about the Soviet food crisis and its catastrophic consequences. Nonetheless, they allowed themselves to be manipulated to the extent that reports about the famine being the work of Nazi propaganda were generally believed. Once again, it became evident that the country with the most effective tools for spreading disinformation was Russia.

The Nazi stigma, planted by Soviet propaganda, stuck to Ammende’s reputation longer than any disgrace generated by reports that he was gay. To this day historians refer to him as an activist controlled and financed by the Third Reich, even though his declared cause – cultural autonomy for minorities – fails to correspond to Nazi ideology.

It is untrue to say that Ammende treated the famine of 1932-1933 instrumentally, as some authors suggest. His brother died of starvation in Leningrad in 1921. Hunger was a personal cause for him, a raw and painful wound dating back to his search for his brother’s grave in Leningrad. Equally, the famine was an international issue at a time when the Soviet authorities were using it as a weapon in their final push against a resistant peasant class on the one hand, and against Ukrainians, who represented the largest national minority in the USSR, on the other. The lack of international response to the Soviet implementation of policies that led to the elimination of entire communities was a personal disaster for Ammende, whose life’s work was the support of ethnic minorities. It was also disastrous for global security and for the new world order established by the Treaty of Versailles.

Nevertheless, it is true that, as a man of German origin and a natural organizer, Ammende liaised with the authorities in Germany to secure the interests of German communities abroad. He was engaged in doing this before Hitler came to power. He also cooperated with the authorities of other countries where he worked: Tsarist Russia; Bolshevik Russia; Ukraine under Hetman Pavlo Skoropadsky and Ataman Symon Petliura; as well as Austria under Otto Ener, Karl Buresch, Engelbert Dollfuss and Kurt Schuschnigg. In 1921 and 1922, he worked for the International Relief Committee to Russia, led by Fridtjof Nansen. His own subsequent relief effort was modelled on this organization. From the creation of the ENK until 1935, he cooperated with the League of Nations, its officials, its secretariat and its various leaders.

Cardinal Theodor Innitzer was more fortunate than Ammende. He was not branded a Nazi, even though his reputation suffered a serious setback after 12 March 1938, when Austrian bishops issued a call to Catholics advising them how to vote in the forthcoming April referendum. The faithful were instructed to support the annexation of Austria into the Third Reich and to welcome Hitler into Vienna on 15 March. The Holy See gave a severe reprimand to the bishops, describing their directive as ‘the most shameful episode in the history of the Church’. However, Innitzer was fully rehabilitated in his lifetime in recognition of the fact that he chose a more balanced and objective position prior to, and during, the Second World War. A few years after his death, the Vienna diocese set up a Cardinal Innitzer Prize, awarded annually to scientists and scholars. This soon acquired the status of an ‘Austrian Nobel’ for the social sciences. In 1997 its laurate was the biochemist Oleh Hornykiewicz (or Hornykewycz), nephew of Myron Hornykewycz, a parish priest for the Greek Catholic community in Vienna between the wars. In 2019 a memorial plaque in recognition of the help Cardinal Innitzer gave to victims of the Ukrainian famine was unveiled at the Archbishop’s Palace in Vienna. A lecture about Innitzer was delivered in the course of the commemorations. The speaker was Timothy Snyder.

Those who survived the border guards, who fired on and killed most trying to escape.

Hungerpredigt. Deutsche Notbriefe aus der Sowjetunion (Hunger Sermon: German letters of distress from the Soviet Union), ed. Kurt Ihrenfeld, Berlin–Steglitz, Eckart, 1933.

E. Ammende. Letter to the editor, Reichspost, 26 June 1933; E. Ammende. Der Massentod schreitet durch Russland. (Die grösste Hungerkatastrophe Europas), (Death on a massive scale sweeps through Russia (Europe’s largest famine)), Reichspost 16 July 1933.

A. Kappeler, Das Echo des Holodomor. Die Hungernot 1932/1933, (The Echo of Holodomor: The famine), Osteuropa, Vol. 70, No. 12, 2020, p. 135.

Izvestiya, 20 July 1933 (also compare Golod v SSSR [Hunger in the USSR] 1929-1934, Vol. 3., Summer 1933-1934, MFD, 2011, p. 486).

Letter from Austrian Ambassador, Heinrich Pacher to Austrian Bundeskanzler, Dr. Engelbert Dollfuss, Moskau, 21 July 1933, Österreichische Staatsarchiv, Neues Politisches Archiv 44, pp. 513–514.

E. Ammende, ‘Famine in Ukraine’, DILO, No. 195, 28 July 1933, pp. 1-2.

‘Das trotz des auf die planmässige physische Vernichtung des ukrainisches Volkes hinarbeitenden russischen Imperialismus massgebende europäische Staaten Freundschaft- und andere Verträge mit Sowjetrussland abschliessen.’ (‘Despite the fact that Russian imperialism is working towards a planned destruction of the Ukrainian nation, Europe’s leading countries are making friendship pacts and other treaties with Soviet Russia’), Reichspost, 17 September 1933, p. 5; also Neue Zeitung, 18 September 1933, p. 2 (source Kappeler p. 137).

Original name of the committee: Interkonfessionelle und Übernationale Hilfskomitee für die Hungergebiete in der Sowjetunion.

The international and interdenominational conference of representatives of all organizations involved in providing aid to those starving in the Soviet Union, which met under the chairmanship of Cardinal Archbishop Dr. Innitzer in the Archbishop's Palace in Vienna on 16 and 17 December 1933, unanimously made the following statements (based on authentic reports and documents, including extensive photographic material):

Contrary to all attempts to deny the catastrophic famine that raged in the Soviet Union until the last harvest, it is emphatically stated that in the course of this year millions of innocent people died. And it is equally irrefutable that in the wake of this mass starvation the most appalling side effects of any famine, including cannibalism, were recorded.2 These sacrifices could have been avoided. While this tragedy was taking place in the Soviet Union, the overseas grain-producing areas were suffering from abundance. World conferences dealt with the problem by restricting grain production. Huge quantities of surplus food stocks were destroyed, a fact that contradicts the most elementary principles of reason and humanity. In a very short period of time, these surpluses could have been transported to the harbours of Odessa, Rostov, etc., using the available means of transport (unused ocean liners).

A further increase in the famine is imminent. Even this year’s relatively good harvest could only bring temporary relief.In view of the renewed threat to the lives of millions, the Conference addresses the worldwide public and urges it to tackle the work of active aid for the unfortunate with all its energy. It is not enough to save the lives of individuals by means of individual aid, as has been the case up until now; immediate measures must be taken to prevent further mass deaths as quickly as possible by means of a generous relief operation. Should there be any doubt about the devastating effects of the famine and the renewed threat to human life, the Conference believes that world public opinion, through its appointed representatives, should find ways to establish the facts. From Hungersnot! (Famine!), 1933, pp. 48-49.

Letter from Bundeskanzleramt to Austrian representative in Vatican, Dr. Rudolhp Kohlruss, 24 October 1933, NPA/364/334, P. 1. Por. also report on Muss Russland Hugern (Human Life in Russia), Vienna, 6 November 1935 to Bundeskanzleramt, NPA 602/175, p. 5.

Available documents make it hard to say whether Cardinal Innitzer was acting specifically at the request of the Holy See or just in agreement with it.

Neues Politisches Archiv. Österreichisches Staatsarchiv, 364, Amtseerinennerung(innen), Vatikan, 27 October 1933 – Bundeskanzleramt 2 November 1933, pp. 332-333.

‘Wide Starvation in Russia Feared: 10,000,000 face death in fall unless aid is given, Head of Vienna Relief Group says’, The New York Times, 1 July 1934, p.13.

E. Ammende, General Secretary of the Inter-Confessional and International Aid Committee for the Starvation District in Soviet Russia, ‘Famine in Soviet Union: Vienna Aid Committee Emissary reiterates statement of conditions’, The New York Times, 11 July, 1934, p.16.

E. Ammende, ‘Relief needed in Russia: Individualist farmers, deprived of grain by authorities, will die unless aided’, The New York Times, 4 August 1934, p. 11.

Congress of European Nationalities, 10th Congress, Bern, 4–6 September 1934, League of Nations Archive, R3932-4-6638-13142-Jacket2.pdf.

E. Ammende, Muss Russland hungern? (Human Life in Russia), George Allen & Unwin Ltd, 1936; Threat of prohibition, intervention of the Austrian association for German foreign workers, Bundeskanzleramt, Vienna, 6 November 1935, Neues Politisches Archive, 602, pp. 170–175.

Human life in Russia, p. 146.

‘My protest is addressed solely and exclusively to all those in the non-Communist world who still confess to the principle of human, in particular Christian solidarity in the face of catastrophes, indeed of unmerited disaster overtaking others – but who are blind and dumb where the fate of the luckless poulation of the Soviet State is concerned.’ Ibid. p. 318.

Ibid., p.146

Ibid., p. 311

Human life in Russia, Introduction by the Rt Hon. Lord Dickinson, p. 8.

Published 23 December 2024

Original in Polish

Translated by

Irena Maryniak

First published by Eurozine (English version)

Contributed by Institute for Human Sciences (IWM) © Ola Hnatiuk / Institute for Human Sciences (IWM) / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTIn collaboration with

In focal points

Newsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Related Articles

The ‘Trump–Putin deal’ again places Ukrainians in a subaltern role. The leaked contract with its fantasy $500 billion ‘payback’ has been compared to Versailles, but the US betrayal recalls nothing so much as Molotov–Ribbentrop.

Ukraine faces its greatest diplomatic challenge yet, as the Trump administration succumbs to disinformation and blames them for the Russian aggression. How can they navigate the storm?