In an unanticipated turn in the sex/gender order, and in party politics in Europe, a far-right woman leader has broken the political glass ceiling in France. Marine Le Pen, president of the French far-right Rassemblement National (formerly Front National) party from 2011-2022, has defied all expectations in several ways. She has steadily brought her political party into the mainstream, is the first woman to have consistently led a major political party in France since 2011, and is the only woman in French history to have made it to the second round of Presidential elections both in 2017 and 2022. A tall woman who likes to pose with wide open arms, and whose deep voice booms on television and at political rallies, she represents not only the normalization of the far-right in France, and Europe more broadly, but also the normalization of a woman political leader who is admired among supporters as a strong woman with masculine features.

Still, as much as she is seen as representing a modern woman with a masculine style of doing politics, can Marine Le Pen be seen as a ‘strongman’ leader? To answer this question, we must first comprehend what are essential qualities of strongman political leadership. By a brief comparison to the political style of figures like Russia’s Vladimir Putin and Brazil’s former president Jair Bolsonaro, and by mobilizing theories of hegemonic masculinity and femininity to analyze Le Pen’s leadership, we can see how Marine Le Pen differs from these leaders in significant ways. Her expressions of hegemonic femininity part from them, as do some – but not all – of the characteristics she performs associated with hegemonic masculinity.

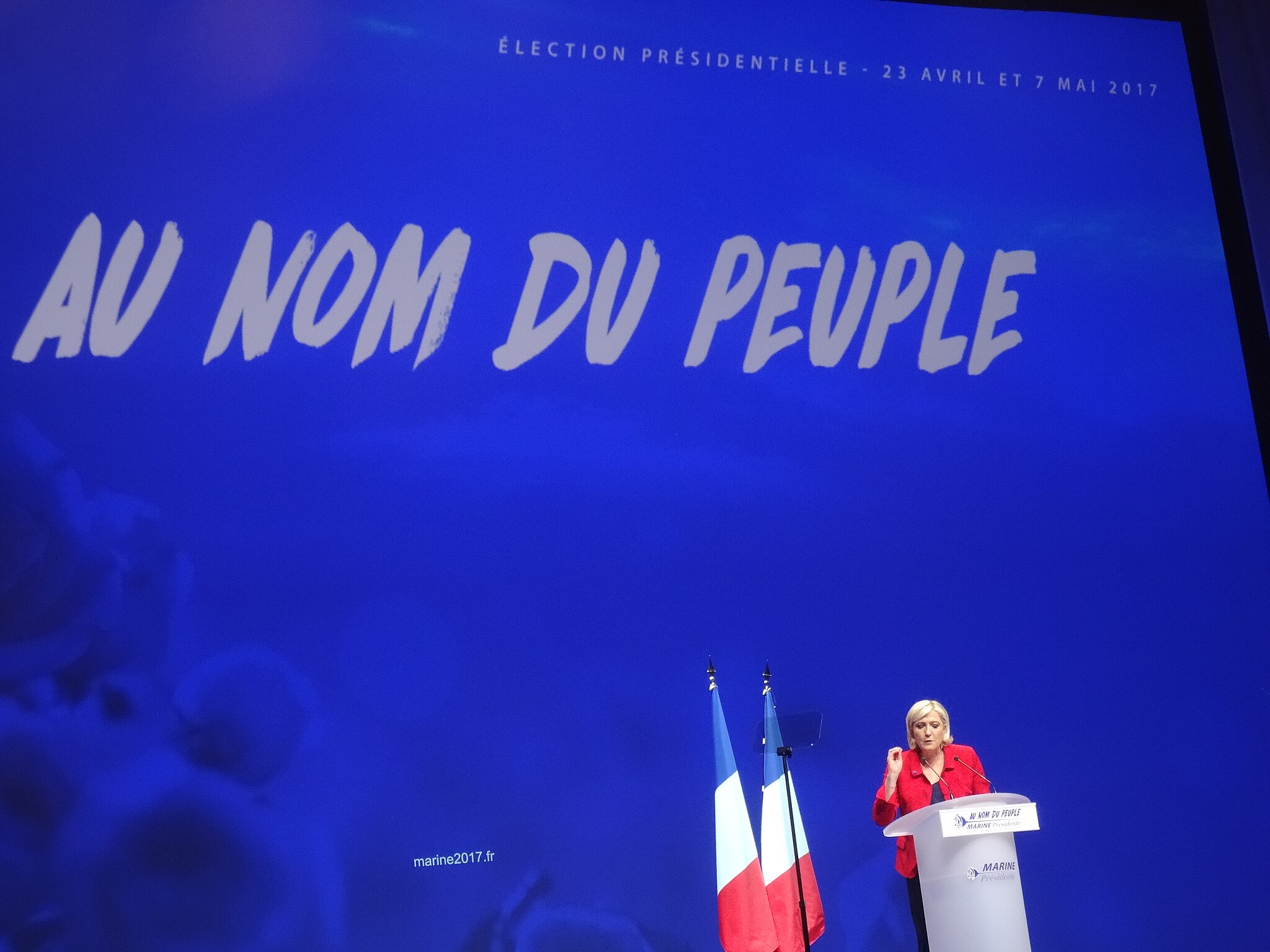

Marine Le Pen at a campaign meeting in Lille, March 2017. Image via Wikimedia commons.

Further comparison to rival far-right 2022 Presidential candidate, Eric Zemmour, shows he represents a regressive and patently patriarchal version of hegemonic masculinity. This did not prove to be popular with the French public. Marine Le Pen’s representation of hegemonic masculinity and hegemonic femininity proved to be more appealing to twenty-first century voters. No longer centred on military masculinity as an ideal, even a strong far-right leader in Europe does not need to build authority and legitimacy around an association with militarism. Instead, Le Pen has cast herself as forceful by conjoining a maternal discourse of national protection with a strong fist in domestic police and border power.

I conclude that Le Pen does not represent typical ‘strongman’ politics. As a woman far-right leader she has been an engine of innovation by positioning herself as a strong and consistent party leader, by breaking several glass ceilings, and by modeling successful female leadership for other far-right leaders in Europe, such as Italy’s Giorgia Meloni. At the same time, as much as she dominates her party with discipline and a cult of personality, she is circumscribed by still needing to show a soft ‘feminine’ side to appeal to voters and to normalize the far right; and also by the pragmatics of a party longing to become a ‘normal’ political party in parliamentary democracy.

Hegemonic masculinity, hegemonic femininity, and ‘strong man’ leadership

Assessing Marine Le Pen’s authority and political style is aided by turning to sociological approaches to hegemonic masculinity and hegemonic femininity. Australian sociologist Raewyn Connell developed an influential theory of hegemonic masculinity, showing how hegemonic masculinity legitimates male dominance not only over and above femininity, but also over and above subordinate masculinities. Her approach to hegemonic masculinity argues that qualities associated with masculinity are constructed around the idealized relationship between masculinity and femininity, where the two are structured as complementary, two ‘opposites,’ which attract through the supposedly natural relationship of desire between persons marked as male, and persons marked as female. These ‘opposites’ are also hierarchical, with masculinity relationally and hierarchically structured over and above femininity, and intersectionally overlap with other categories such as race, ethnicity, and religion. Hegemonic masculinity cannot exist without its relational reference to femininity, and also without a hierarchy of dominant masculinity above other, lesser valued, masculinities and femininities.

American sociologist Mimi Schippers enriches Connell and Messerschmidt’s work by arguing that gender hegemony must not only consider hierarchies between masculinities, and of masculinity over femininity, but also between femininities. Whereas Connell and Messerschmidt argued that there is only hegemonic masculinity, but no hegemonic femininity, Schippers rather argues that hegemonic femininity exists, while it also perpetuates the dominance of masculinity over femininity.

Hegemonic masculinity is expressed in qualities such as a deep voice, physical strength, and desire for the feminine object. Hegemonic femininity is expressed in quality contents that are seen as supporting hegemonic masculinity as complementary to, and over and above, hegemonic femininity. For example, these include a person’s qualities such as demure physicality, passive desire for the masculine object, a soft voice, and emotional vulnerability.

Schippers also identifies ‘pariah femininity’ as a form of femininity that is socially undesirable and contaminates the so-called naturally (i.e. hegemonic) hierarchical and complementary relation between masculinity and femininity. It is embodied by disruptive figures such as the ‘butch,’ the ‘bitch,’ the ‘slut,’ or an ‘aggressive woman.’ Pariah femininity contains the quality content of hegemonic masculinity, but embodied and performed by a person marked as female.

Seen through this theoretical lens, what makes Russian President Vladimir Putin, former Philippine President Rodrigo Roa Duterte, former Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro, and Hungarian President Viktor Orbán into ‘strong man’ political leaders?

I argue that the following cluster of four closely related features typify strongman leaders. It must be noted that these features together form an ideal type, and may not be entirely descriptive of any single leader. The first feature is a self-representation and style of doing politics which links their authority to masculine violence, militarism, and the state’s military and police power.

Secondly, strongmen rule their political parties, and their respective states, with little room for others to contest their power. True parliamentary politics are therefore antithetical to strong-man politics, as parliamentary politics entail extensive negotiations, compromises, oral debates, and a degree of unruliness and unpredictability in political outcomes that is unacceptable to strong-man politicians. China’s Xi Jinping is one such figure, who successfully brought an end to term limits so that his path to continued dominance in China and over his party could continue unabated. This too is an expression of hegemonic masculinity. It expresses an absolute hierarchical and patriarchal mastery, including over subordinate men, which does not yield to compromise.

Thirdly, strongmen buttress themselves as antithetical to contamination by hegemonic femininity, and relatedly, resist contamination by homosexuality. While there are other styles of masculine political leadership now on display in world politics, such as Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s softer, caring image with touches of hegemonic femininity having entered into the quality content of his masculinity, strongman politics are antithetical to association with femininity or homosexuality. Heterosexuality is explicitly deployed as a marker of dominance over women, and dominance over other men and sexualities.

Fourth, strongmen leaders foster around themselves a strong cult of personality. They must be at the centre of the political party, and even of the state. Strongman leaders often fail to develop a close second in command, as they cannot share power, attention, or invest in a figure who may be seen as their political inheritor. The cult of personality they promote invokes intense emotional attachments from followers, and repugnance among critics.

Does Marine Le Pen express these qualities of being a feminine ‘strongman’ politician? Yes, and no. Drawing from ethnographic observations and interviews conducted between 2013-2017, and from analysis of her more recent role as the leader of a sizeable parliamentary group in the National Assembly, I show where her masculinity and femininity part from, but also overlap with, strongman politics. Methodologically, I do not focus on media analysis, which has become a dominant method of analyzing far-right politics today. Instead, the essay focuses closely on the explicit gendered performances of Marine Le Pen, its mediation by party communication, several of her policy positions, and their reception by her followers through ethnographic and interview data.

Compared to far-right rival Eric Zemmour, Le Pen represented in 2022 a version of tough and modern femininity that was more effective than Zemmour’s throwback masculinity. At the same time, Le Pen has shown herself to be a tough political leader, with a disciplined party behind her. Facing now the pragmatics of parliamentary politics, Le Pen must act more as parliamentary mediator within her group and in working with other political parties, than as a strongman authoritarian. As a woman she is hemmed in by expectations of hegemonic femininity which prevent her from expressing unadulterated dominance and violence, while her ambition since 2012 to position her party as mainstream also circumscribes her displays of strongman authoritarian politics.

A ‘beautiful woman’

Entering the world of the far-right French party as a qualitative political sociologist from 2013-2017 meant an immersion into a political party with an intense cult of personality. When I began my research in the first months of 2013, Marine Le Pen was still a fairly new leader to the party. Having been elected as party president in 2011, replacing her father who had been FN president since its founding in 1972, FN ‘old timers’ were still adjusting to a woman of a younger generation leading their movement. The view from inside the party was one that felt like a club, full of lore, memories, rituals, friendships, and rivalries in relation to the Le Pen clan. Membership in this club meant a strong familiarity with the Le Pen dynasty at the heart of the party, a sprawling, and even somewhat glamorous family, whom Jean-Marie Le Pen openly displayed as part of his political persona.

Marine Le Pen has known to capitalize on this image, fostering a celebrity-like aura within her party and beyond. One of my first ethnographic encounters with party members was when I visited the party headquarters in the city of Nice. I had begun my immersive research in the southeast of France. With a large resettlement of pieds noirs, white French citizens who had lived for generations in French colonial North Africa and had relocated to Metropolitan France following Moroccan and Tunisian independence in the 1950s, the southeast has long been the radical right party’s heartland. Situated several streets away from the city’s glamorous yacht-filled harbour, the FN office was an understated affair. It was in need of a new coat of paint, and stood on a polluted and decaying street. But the offices were filled with the energetic activities of the group of activists I encountered that day.

When I entered the office, I was greeted with the chivalric élan of a group of men who expressed their own hegemonic masculinity by letting me know that, as the only woman present, I had supposedly lightened up the atmosphere. The men were otherwise busy preparing for the municipal elections of March 2014. Most had reached the age of retirement, small independent businessmen who are the traditional petty bourgeois base of the party and had joined the party when Marine’s father, Jean-Marie Le Pen, was party president. Marine Le Pen’s image was plastered on posters throughout the office. I became accustomed over the years to see her image covering the walls of the various cash-strapped FN locales I visited.

I had asked the men in the office whether they thought it mattered that their party was now led by a woman. Jeremy, an FN politician who was in the Nice headquarters that day, shrugged off my question. He thought that the main difference between Marine and Jean-Marie Le Pen, the party’s founder and Marine’s father, was that she was no longer content with playing the role of the agent provocateur, but had a will to power. As opposed to her father who would run for presidential elections as an act of defiance, Jeremy saw Marine as a real presidential contender.

Although Jeremy had denied just a few minutes earlier that the party leader’s gender mattered, he then named each major French female politician that came to mind, and concluded that Marine was undoubtedly the most beautiful. Later, sitting with several of the activists on an old sofa in the welcome area of the office, my questions about Le Pen – which never touched upon her physical appearance – resulted in an extended discussion among the men regarding how they found her to be attractive. Their view of her as beautiful did not trivialize or delegitimize her as their leader. On the contrary, they were pleased with her looks and saw her brand of corporality as setting her apart from the rest.

The men spoke of Marine with love, admiration, and even desire. The language they utilized and the sentiments they expressed when describing support for Marine – always called only by her first name – was infused with highly feminized imagery. Many political leaders can only dream of the kind of personal feelings and projections Le Pen’s followers expressed for their leader. Le Pen was treated with such symbolic multivalence that at times it was difficult to make sense of how she could be admired as, for example, the next General de Gaulle, and at the same time be seen as a strong but wounded woman who has nobly kept her children out of the public eye while serving the nation.

As I describe elsewhere in my article, ‘Daughter, Mother Captain’, younger followers admired Le Pen for her modern, forward-looking views, and identified with her as a maternal figure who fearlessly sought to protect and care for the younger generations. Her own self-projection via party communication links her unabashedly to Joan of Arc, the medieval warrior martyred during the Hundred Years War, and who is one of the most symbolically rich figures in French national iconography. Association with Joan of Arc was long integrated into the symbolism of the French far right under Jean-Marie Le Pen’s leadership. One of the most important annual rituals of the party has been a May 1 march in Paris, ending at a golden Joan of Arc sculpture in a sumptuous square in the heart of historic Paris. MLP seamlessly stepped into the role of associating her own leadership with that of Joan of Arc, incorporating the warrior-martyr-virgin’s symbolism into her own self-expression as a devoted unmarried warrior serving the nation.

Representing a new kind of female leadership in France, Le Pen has not hesitated to speak of herself as a woman, and as a mother. Younger male and female followers were attracted to this image, since they believed she represented a leader for whom politics was not just a career choice, but something that came from the heart. Older adherents saw her as a beloved daughter who grew up in a complex political family, a childhood experience that gave her the toughness and faith necessary to be a great leader. Many admired her physicality as a woman, commenting on her long legs, and seeing her as embodying fierce maternal care and protection which they saw as setting her apart from other leaders. Party adherents who would attend FN events around the country would relish seeing her in person, in clothes she would only wear at internal party events, such as short mini-skirts and towering stiletto heels. Embodying features of hegemonic femininity, her femininity was a strong source of appeal across generations.

The first event where I saw Marine Le Pen in person was at the annual May 1 Paris march in 2013. Striking up a conversation with a group of excited retirees who had bussed in from the south of France, I joined them to go and listen to MLP’s speech at the final rally. We looked upwards towards the stage where MLP’s elevation appeared to make her larger than life as she gave a speech in a suit that matched exactly that of her father’s, who was also seated on stage. Bursting with excitement, and completely ignoring MLP’s speech, one of the women exclaimed to me, ‘She has extraordinary legs! Extraordinary!’

My penultimate glimpse of Le Pen in the flesh came at the closing of her presidential campaign launch in Lyon in February of 2017. At a Saturday night gala dinner for party members, the three-course meal ended with a live performance by ABBA impersonators. The already festive mood became even more boisterous as party VIP’s spilled on to the dance floor. Gala attendees then crowded around them, competing to catch a glimpse of Marine at the centre, as she danced and sang to ABBA songs on her stiletto heels while her blonde coiffe reflected the sparkling strobe lights.

The next afternoon she gave a lengthy speech unveiling her presidential campaign platform, wearing one of her signature masculine suits. Those who had been present at the gala dinner knew that just the evening before, this same commanding woman had danced alongside them with abandon on a dance floor.

A fighter

At the same time as some saw Marine Le Pen in highly feminine terms, others saw her through a lens that cast her as a female combatant with masculine features. Nicole, a Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes politician whom I met in 2016, commended MLP for not sexualizing herself, and for her masculine attire. She compared Le Pen to the Socialist party’s Ségolène Royal, the first woman presidential candidate in French history, who lost the 2007 presidential elections to centre-right candidate, Nicolas Sarkozy. Royal, in Nicole’s view, had made the error of excessively sexualizing herself during her presidential campaign. Yet, despite MLP’s ‘great legs,’ Nicole pointed to how MLP always covers her legs and is careful to wear a masculine, black suit at major political events.

I had met Nicole at a different dilapidated party office, this time in the eastern city of Lyon. The office has since moved location, but at the time was located at the polluted cross-roads of a motorway exchange and near the city’s central bus station. I had come to observe an FN evening welcoming new party members in the Fall of 2016, in the lead-up to the 2017 presidential and parliamentary elections. I observed Nicole’s welcoming speech, including navigating a bizarre moment of a woman wearing a hijab who presented herself to the group as choosing to become a new FN member because of a revelation that Jean-Marie Le Pen represented Allah’s will. Nicole could not hold back, and responded to the woman that perhaps her values do not align with those of the FN – probably a thinly veiled reference to the woman’s hijab.

At the end of speeches, I approached Nicole, and she seemed pleased to discuss in detail her views on women in society, and Marine Le Pen as a female leader. She explained to me that she had studied law as a university student, but then upon marrying and giving birth to several children, she had decided to abandon her professional career to become a full-time caregiver. Now that her daughters were no longer little, she was inspired to enter politics when Marine Le Pen became a party leader. For Nicole, Le Pen represented a kind of feminine strength she admired greatly, and she believed that Le Pen was the only political leader truly fighting for women’s rights. To Nicole’s own surprise, Nicole moved from a solid centre-right position, to becoming an FN politician thanks to MLP’s personal inspiration.

Nicole spoke to me at length about her concerns regarding the pressures placed on adolescent girls in terms of their dress and appearance. On the one hand, young girls were being sexualized by media, and were sexualizing themselves, through outrageously skimpy clothes. On the other hand, she strongly objected to Islamists ‘forcing’ young girls to cover themselves rather than asserting their right to ‘be free.’ Observing how her daughters and their friends navigate these pressures had led her to become an FN activist and then FN politician, especially once MLP became party president.

Nicole’s evidently low-budget campaign video for her own 2017 election campaign showed her speeding through a city on a powerful motorcycle, clad in a black leather suit and a heavy dark helmet. Like Le Pen, she displayed a dual masculinity and femininity, signaling that she was a free and powerful woman in tight leather clothes, but also through the symbolic valence of masculine athleticism and daring. Nicole was emulating Le Pen’s emphasis on her protectiveness as a tough woman, in line with supposedly protecting women against Islamic fundamentalism and its unequal treatment of women.

Interviews with young party activists also showed how they admired Le Pen for her masculine virtues, especially in her authoritative style of doing politics and leading her party. A thirty-year old man from northern Burgundy plainly stated, ‘She’s a woman who does politics like a man.’ Another young man explained: ‘Her profession involves power … She goes sailing, she likes intense sensations. Historically, women didn’t like to take risks, and sports involve taking risks.’

Some young women expressed enormous admiration for MLP as a personal inspiration for them. A young woman activist commended MLP as a virile and masculine figure: ‘There are few women… who display, I dare say, as virile a force as her. It’s rare … It’s always nice to see a woman who can lead a great political movement, France’s premier party, like a man. With force, with conviction, with righteousness, with honor. These are qualities which are, quote unquote, masculine.’

A male law student in Paris who was twenty at the time expressed the view that MLP could also be viewed as especially authoritative, representing the firmness of a figure like General de Gaulle, more so than other prominent male politicians: ‘She has that verve, that strong fist, which makes her a real head of state. In the Fifth Republic’s constitution, General de Gaulle dictated the constitution so that the head of state would be a captain … I absolutely see Marine Le Pen in this captain’s suit. Whereas someone like [current president] François Hollande or [former president] Nicolas Sarkozy – for me this isn’t a suit tailored for them. I see Marine Le Pen as someone who is more capable of fulfilling the functions of head of state compared to the others.’

Similarly, according to a male FN Member of the European Parliament: ‘Many French people now miss General de Gaulle, who was a man of great conviction. I feel that with Marine Le Pen, we finally have found someone who has the authority General de Gaulle had.’ Rather than seeing Le Pen as representing a kind of pariah femininity, these admirers rather saw her as a remarkable woman with masculine virtues.

The soft grip of maternal protection

Unlike some far-right women in US politics such as politician Lauren Boebert who proudly brandish guns as markers of their masculine prowess, Marine Le Pen has carefully stayed away from associations with militarism, and especially with far-right militia organizations. Of the numerous transformations brought by MLP’s party leadership, one notable change has been her remaking of symbolism linking the RN to fascism, and removing herself from association with militia-like figures, symbols, and activities. MLP’s 2017 presidential campaign heralded a rebranding of the party’s image. Since the FN’s founding in 1972, the tricolour flame has been the party’s central symbol. A sign associated with Italian fascism, and still the symbol of Giorgia Meloni’s Fratelli d’Italia party in Italy, Jean-Marie Le Pen claimed when his party was founded in 1972 that the party was too poor to commission a new graphic design symbol. Such pragmatism aside, the FN symbol clearly links the party to the history of Italian fascism.

Militarism under Jean-Marie Le Pen’s FN leadership held a prominent but somewhat ambiguous place. The FN from its founding was linked to veterans’ organizations from the Algerian Wars. However, as much as JMLP used to boast about his past role as a military officer, and even claimed he had committed acts of torture as a military intelligence officer, the party was always distinct from even more reactionary far-right movements from the 1970s which had mobilized violence as a political tactic, especially against the liberal and Marxist 1968 student movements.

JMLP’s aspirations were to have a voice in party politics, an ambition that has checked the party’s outer expressions of violent radicalism. As he aged, Jean-Marie Le Pen’s self-presentation within his party, and to the French public at large, was not so much as a violent or authoritarian ‘strong man’ representing the old fascist ranks, but was of a grinning provocateur who relished shocking guests at a dinner table. With the benefit of hindsight, one can see him as a stylistic precursor to Italy’s Silvio Berlusconi, more than precursor to Jair Bolsonaro or Rodrigo Duterte.

Marine Le Pen has proven to be a long-term strategist who has effectively re-organized the party from top to bottom, and who also has a strong affinity for political communication. In line with rebranding the party’s image, Marine Le Pen commissioned a softening of the tricolour flame symbol. It is still a party symbol, but now looks rounder and less brutish in form. Such subtleties matter to her in rebranding the party. In parallel, and unlike her father, Marine Le Pen has explicitly fostered a very personalized visual style, placing her image as a strong but caring woman at the centre. Her 2017 campaign symbol was a blue rose, and her 2022 campaign was centred around a series of platforms called ‘M La France,’ with ‘M’ being a reference to her first name, Marine.

I observed from ethnographic observation how her leadership also brought on an active suppression of anything that looks militia-like at party events. At the annual FN march I attended in 2013 in Paris, several men with violent and fascist slogans were marching with the FN supporters. Several FN security guards – perhaps volunteers, although I could never verify who they were – quietly but firmly approached them and insisted that they leave the march. The annual march always garnered strong media attention, and I interpreted this moment as a deliberate reshaping of the party image.

While Le Pen has pushed out appearances of militia violence within the party, she and her followers express admiration for police and military forces, articulating a yearning for a strong French state which commands respect, law, and order. Marine Le Pen’s final speech at Place de l’Opéra was delivered in front of a giant poster of Joan of Arc in warrior armour. The new image being conveyed was that of a disciplined political party, with no room for chaos or street violence. The group of retired women I had met at the event were delighted to greet the police officers accompanying the march and rally to ensure compliance with law and order. One woman even tried to entice some of the police to join the march. This contrasted markedly with a different event I observed four years later, at a left-wing rally for Jean-Luc Mélenchon, where attendees lining up to enter the rally in Dijon instantly hurled insults at the police, calling them fascists and other such epithets.

I also witnessed military-like discipline among party members. At MLP’s presidential campaign launch in Lyon in early 2017, I observed how FN supporters displayed respect for their party’s rules and their leader’s authority. Just prior to MLP’s 2017 presidential campaign kickoff speech, I sat next to two working class men from the Avignon area who had brought an American flag and a French flag to the event. They had intended to wave both flags throughout MLP’s speech, as a gesture of solidarity with Donald Trump’s election in the United States. The FN’s private security personnel approached them while we waited in the auditorium and before MLP’s crowning speech began and asked them to remove the American flag. The men quickly obliged, and were embarrassed that they had not been warned earlier.

At the end of MLP’s speech, the crowd in the main auditorium had emptied out, and were milling about the enormous foyer of the congress hall. They were buzzing with excitement following Marine Le Pen’s rousing speech. Suddenly, Marine Le Pen entered the hall, with a crowd of journalists surrounding her. A university student I had been chatting with stopped mid-sentence and informed me, ‘we must follow Madame La Présidente.’ The activists still present in the hall quickly regrouped, and without needing to be told what to do, assembled into a line behind MLP as she strode forward, towering above the rest with her tall physique and high heels. Embodying charisma, MLP commanded respect from party followers.

A softer, modern masculinity: Marine Le Pen versus Eric Zemmour

The 2022 presidential elections in France were marked by the arrival of yet another radical-right presidential candidate who was framed by the media as a ‘disrupter’ aiming to remake the map of rightwing politics in France. Journalist Eric Zemmour made a splash by declaring his candidacy in 2021. Zemmour had spent much of his career since the 1970s writing as a provocateur, with increasingly rightwing views and since 2005 in his writings on the French ‘crisis of masculinity.’

Mobilizing a professorial-like articulation of French grammar employed only by the most elite French politicians and academics, Zemmour has styled himself for decades as a rightwing intellectual who dares to speak the truth about the ‘feminization’ of French men in politics and in everyday life. Well before the surge in radical rightwing populism in Europe, Zemmour had shifted in the mid-2000s from a fairly mainstream political commentator writing in the centre-right Le Figaro newspaper, to a more controversial polemicist insisting that men needed to reclaim their rightful place in society.

In his 2006 book, Le Premier Sexe, supposedly writing against Simone de Beauvoir, Zemmour proclaimed that one does not ‘become’ a woman, or a man, but that men are born men, and women are born women. Zemmour has spent the subsequent fifteen years of his career enjoying the attention he garners from such provocations. He has since become a prominent television personality, especially on CNews, a channel founded in 2019 as a French rightwing news outlet.

Zemmour’s Le Premier Sexe gave him a platform to spread his view that men are naturally ‘sexual predators,’ whose feminization has putatively resulted in a deep void in the psyches of both men and women. In one of many interviews afforded him following publication of his book, he described in 2006 how he had observed a family on a high-speed train where the father had held the child for the duration of the train ride, whilst the mother read a book. Zemmour explained that such observations show how men are now recast as ‘second mothers.’ This family was symptomatic of the denial of men as primal beings, resulting in a social and civilizational catastrophe. Interestingly, in the same interview, Zemmour also critically assessed the relationship between then socialist leader Ségolène Royal, and her romantic partner François Hollande.

Embodying all that is supposedly wrong with contemporary gender roles, Royal, he argued, was both a beautiful woman and a virile figure; and in turn, Hollande was a feminized male. In the terms of hegemonic masculinity and femininity dominant in 2006, Zemmour was arguing, in effect, that Royal and Hollande were failing to embody hegemonic femininity and masculinity. Rather than a relationship built on two complementary and putatively natural opposites, Royal was a woman exhibiting masculine traits, and Hollande was a man exhibiting feminine traits – symbolizing all that is wrong with the French left, and with French masculinity in general. Zemmour has continued to espouse these positions, becoming progressively more provocative and with an ever-greater podium from which he could broadcast these views on television and radio.

His announcement in late 2021 that he was launching a bid for the presidency was heralded by some as a game changer for Marine Le Pen, who was supposedly being outranked to the right by a man who could finally unite the bourgeoisie with the working class. Having long been a fixture in Parisian media circles, media pundits across the political spectrum took seriously that he was a real challenge to Le Pen’s candidacy.

Zemmour launched a reactionary campaign, one which proved to be unpopular with women voters, and not terribly popular with men either. French political scientist Nonna Mayer has long studied the gender gap in voting for the French far right. Under Jean-Marie Le Pen, the Front National never appealed as much to women as it did to men. Yet, Mayer’s recent review of the 2022 elections shows that Marine Le Pen has closed the gender gap, and controlling for factors like social class and religion, women were as likely to vote for her as men. Zemmour, by contrast, appealed far less to women voters.

Although not much in substance truly distinguished most of his platforms from that of Le Pen’s, the main point of departure between Zemmour and Le Pen is that Zemmour presents a strongly reactionary view on gender and conservative family values, and is more overtly racist than Le Pen. As Nonna Mayer brilliantly summarizes, Zemmour’s ‘excesses made [Marine Le Pen] look moderate and reliable’ Zemmour’s radicalism has expressed itself in his shameless support of the ‘great replacement’ theory, which posits that white Europeans are being demographically replaced by Muslim immigrants to France and Europe.

However, it is also on the terrain of gender and sexuality that he has fashioned himself as a reactionary provocateur. His 2022 public engagements continued to insist on the need to return to old-fashioned patriarchy, and his official campaign material declared, ‘We are the heirs of a civilization which sees the relation between men and women in terms of complementarity.’ Complementarity here is a reference to the putatively natural, and complementary differences between the sexes. With a campaign platform that seemed to implicitly acknowledge that he had a woman problem in his electoral appeal, his campaign tried to frame him as seeking to protect women’s equality and women’s rights by defending their virtues ‘as they are.’

Since her election to party leadership in 2012, Le Pen has decisively moved her party’s formal platforms away from reactionary conservatism regarding gender, sexuality, and women’s rights. While she is reluctant to label herself a feminist, like Italy’s far-right Giorgia Meloni, she decisively articulates an image of a strong woman leader, an unmarried mother with unbridled ambitions for herself and her party, and a political leader who authentically cares about women’s ‘liberty’ and needs. Whereas far-right parties in post-socialist Central and East Europe espouse patriarchal and homophobic views, Marine Le Pen has made a very simple calculation that in order to attain power in France, it is necessary to remake the far-right from a men’s club to a party that attracts women voters.

She and the RN’s official program make no negative statements about homosexuality or same-sex marriage, nor is there a discourse of ‘returning’ to bygone forms of hegemonic masculinity and femininity and the traditional sexual division of labour. She has cast such issues as a distraction from the party’s bread-and-butter platforms. Le Pen’s 2022 political platform stated almost nothing about gender or even women, but rather focused on ‘the family.’ Even there, the family was not treated through a lens of socially conservative politics. Where protection of families was mentioned as a campaign promise, it was cast as fighting for sustaining the purchasing power of families, and for increasing support of caregivers, rather than any moral claims towards needing to defend heterosexual families and marriage.

A subtle but telling difference between MLP and Zemmour’s 2022 programs can be found in their respective approaches to reproductive technologies. Mimicking the rightwing conservative discourse of La Manif Pour Tous, the 2013 social movement which mobilized in France against legalization of same-sex marriage and was an early ‘anti-gender’ movement, Zemmour claimed to be protecting the French family by ensuring that no child would be born without a father via medically assisted procreation. MLP’s campaign rather promised to ensure strict enforcement of France’s current moratorium on surrogacy, and to block recognition of non-biological parents for French children born through surrogacy outside France’s borders. Unlike Zemmour’s proposal, Le Pen’s reproductive program makes no mention of gender relations or men’s rightful place in the family, but rather emphasizes that surrogacy remains a controversial topic in France, and that French citizens need to respect French law and sovereignty on the matter.

The 2022 presidential, and then parliamentary elections indicate that these differences in platforms, and in gender performances, had significant effects in their respective appeal to voters. Zemmour garnered 7% of votes for the Presidential elections, and his party attained no seats in the Parliamentary elections. By contrast, Marine Le Pen’s strategy has paid off since 2012. In 2022, she once again made it to the presidential run-off, and while she lost to Macron, she achieved 42% support among voters, narrowing the gap between her and Macron compared to the 2017 elections.

More dramatically, her Rassemblement National Party attained an unprecedented 89 seats in the National Assembly, constituting for the first time a political group in Parliament. As a grouping the RN is afforded more speaking time during Parliamentary debates, and is provided additional funding. The far-right RN is currently the largest opposition group in the French National Assembly.

A ‘Strong Woman’ remaking European politics

A ‘strong’ and disciplined leader who also propagates the view that the French state needs to be harsher in its law-and-order policing of Islamic fundamentalism, criminality, and violence, and ‘protection’ of borders from illegal immigration, Le Pen does not represent unbridled masculine violence as do strongmen like Vladimir Putin. And while she dominates her party with a powerful cult of personality, flexing her muscles in several ruthless moves, such as expelling her father from the party for his indiscipline in 2015, and her swift divestment of former right-hand man Florian Philippot after the disappointing 2017 election results, Le Pen does not oversee her party with the kind of total dominance Putin does over his United Russia party. Having recently stepped down as party president to oversee the RN’s parliamentary group in the National Assembly, she is now comfortably influencing from behind the scenes. Her young protégé Jordan Bardella has formally taken over the party leadership – although the outcome of the leadership race was foretold from the start thanks to Bardella’s obvious status as Marine Le Pen’s personal protégé.

She is a tough woman representing softer modern masculinity. This toughness is expressed in style, and substance. She embodies traits associated with hegemonic masculinity in her appearance and public performances, and in sustaining unquestioned dominance over her party. Her policy positions also express a harsh disciplinary approach, especially towards immigrants and the European Commission.

Still, she is more like Orbán than Putin. Neither politician incites followers to commit acts of violence. Both Le Pen and Orbán dominate their parties through a cult of personality, while also sustaining some participation in parliamentary democracy by allowing for voices of dissent within their respective political parties, and in their public debates with other political actors nationally and internationally.

However, Le Pen diverges from Orbán in her more overt expression of hetero-sexuality. Unlike Orbán, her body is deliberately mobilized as a public platform through which she projects her image as a modern woman who is different from professional politicians. By wearing miniskirts at insider party events, showing a hint of knee in campaign posters, her apparent refusal to remarry, and her regular and willing appearances in glossy French gossip magazines, Le Pen projects an image of a woman with a joie de vivre and a penchant for pleasure which few women politicians of her stature portray.

In the latest chapter of her astonishing political career, Le Pen has now turned to a new role; shepherding her political grouping to act as a united force in the French National Assembly. As was seen with a proposal to enshrine the right to abortion in the French constitution in November 2022, Le Pen was effective in convincing her grouping to support a constitutional right to abortion which was more limited in scope than the original proposal. Needing to bring together social conservatives in her party who oppose abortion, and RN representatives in Parliament who are socially liberal regarding abortion and same-sex marriage, the RN group’s compromise position of supporting a constitutional protection of abortion up to 14 weeks of pregnancy indicates that Le Pen is learning to act as a parliamentary negotiator and deal-maker within her grouping. However, Le Pen is still learning the ropes. It is too early to determine what kind of authority she exerts in her new role, and whether the grouping will operate with a stable mode of compromise and cohesion.

Regardless, with each passing year so far, her party looks more and more like a normal parliamentary party. Le Pen has not succeeded in becoming the President of France, but she has achieved other goals which seemed unimaginable in 2011 when elected party president. She has made the RN into a legitimate political force assembling a diverse social, political, and geographic coalition, while united around its core platforms of racism, anti-immigration, islamophobia, strident nationalism, and a yearning for the strong Gaullist state.

Her putative modernity, and her path-breaking nature as a woman leader in France, are worrisome. Marine Le Pen’s proven ability to make ever-more room for herself and her party at the table of national politics. The means by which she is leading a deep transformation of French politics by mainstreaming the far right, and her remaking of political masculinity and femininity, have set her apart as a change-maker in France and across Europe.