Bankrupt

Wespennest 189 (2025)

Bankruptcy in nineteenth-century parables of capitalism; billionaires, bankruptcy and the American obsession with money; and why the refusal to accept the end makes life worse.

Born in Hungary before becoming a communist in Germany, then a French Foreign Legionnaire, then a wartime propagandist for the British government – but, above all, a writer and thinker – Arthur Koestler was one of the most intriguing intellectuals of the twentieth century. Michael Scammell, the author of his official biography, ‘Koestler, The Indispensable Intellectual’, spoke to Eurozine partner journal Letras Libres about Koestler’s life.

Daniel Gascón: You have said that there was a yearning for utopia in Koestler and other writers. What does he have in common with other twentieth-century writers, and what makes him special?

Michael Scammell: What Koestler had in common with so many writers of his era (and what distinguishes him and them from our present generation) was hope. No matter how disillusioned they became with the societies in which they lived, or disappointed by their failures, both personal, social and political, they retained what looks to us now like a naïve belief in human possibilities and a conviction that the future would be better. Much of this optimism was fuelled, consciously or unconsciously, by the apocalyptic promise embodied in the October Revolution in Russia and the hope that the utopian goals set by the French Revolution – liberty, equality, fraternity – might at last be realized everywhere. We are only too familiar now with the catastrophic failures of the Soviet experiment, but you have to remember that those ideals held powerful sway throughout most of the last century (and are by no means dead even now).

Tony Judt called Koestler ‘an exemplary intellectual’, Christopher Hitchens ‘a zealot’, and Mario Vargas Llosa has said that he was more a journalist than an artist. Do you agree with these descriptions?

I agree with Judt, if by ‘intellectual’ we mean someone who devotes the better part of his life to investigating ideas and if necessary sacrifices his comfort, his reputation, and even his friends for them. I disagree with Hitchens, because despite the element of zealotry in the way Koestler first embraced a variety of beliefs and political movements, he never entirely lost his critical faculties and was fearless in confronting his disillusionments when concluding he had been wrong. As for Vargas Llosa’s criticism, it was commonplace in Koestler’s lifetime, and, as Koestler pointed out, had also been levelled at a celebrated predecessor with similarities to Koestler: H.G. Wells. There is some truth to the charge, given the enormous size of Koestler’s output and his later turn to scientific interests, but I believe it is based on too narrow a definition of art. As someone who has written nonfiction all his life – and taught it at college – I would say there is an art to writing nonfiction that transcends journalism and expresses truths in ways that are perhaps not as sublime as the best poetry and fiction, but are none the less valid and effective for that. I would also say that, apart from Darkness at Noon and certain passages in Arrival and Departure and Thieves in the Night, Koestler’s best work is to be found in his nonfictional autobiographies, Dialogue with Death, Scum of the Earth, Arrow in the Blue, and The Invisible Writing, and in the best of his essays.

You write about Koestler’s fondness for alcohol combined with a strict working discipline, and an astonishing capacity for absorbing ideas. Could you elaborate a bit about this capacity, and mention his more important influences?

It’s hard to say much without indulging in psychoanalysis, and I don’t have the tools for that. Koestler seems to have had the constitution of an ox, and his drinking and work habits probably owed more to his genetic makeup than to psychological factors – though the latter must have played a role, of course. As for ideas, Koestler had a phenomenally assimilative mind and an astonishingly good memory. He read voraciously and was able to pluck quotations and ideas from his vast store of reading seemingly at will. I don’t see ‘influences’ at work in this aspect of his life (except inheritance), and I think his ideas are best discussed in the context of your other questions.

As a youth, Koestler travelled to Palestine. That is where he started his journalistic career. Later he had different views about Israel, Zionism and Jewishness, and he was accused of anti-Semitism. Could you explain his ideas about Zionism and Jewishness, and why you disagree with the anti-Semitic label?

Koestler had a rather peculiar approach to Zionism. In his youth he suffered a great deal (more than he later admitted) from anti-Semitism, and his goal in travelling to Palestine in 1926 was not so much to build a new Jerusalem as to build a sophisticated, European type of society in which Jews would all be equal and as good as anyone else. He grew disillusioned by the provincialism of Palestine, however, and repelled by the influence of religious Judaism, and returned to Europe after just four years. It was the Holocaust during World War Two (the very pinnacle – or should I say nadir – of anti-Semitism in modern times) that restored Koestler’s interest in, and sympathy for, the Jews in Palestine, and he was a fierce and influential supporter of an independent Israel, devoting two books to that cause, the novel Thieves in the Night and a nonfictional account of the struggle for independence, Promise and Fulfilment. But Koestler was never uncritical in his support of Israel, and he infuriated huge numbers of Jews in and out of Israel by his novel theory that Jews in the diaspora should either move to Israel (thus fulfilling the annual Passover vow to be ‘next year in Jerusalem’) or assimilate, saying it was the only way to rid the world of anti-Semitism. Towards the end of his life he elaborated on this theory in his book, The Thirteenth Tribe, in which he maintained that the Jews of Europe were mostly descended from a North Caucasus people called the Khazars, not one of the tribes of Israel, and therefore had no reason not to assimilate. His goal again was to eliminate the evil of anti-Semitism, but his book boomeranged in ways he hadn’t foreseen. First of all, Jews in the diaspora resented his suggestion that they should move or give up their special identity, and pointed out that Koestler’s theory only reinforced anti-Semitism; secondly, it was seized upon by Arab politicians as proof that the Jews shouldn’t be in the Middle East at all and that Israel was a fraud. This wasn’t at all what Koestler had in mind and he reaffirmed his support for Israel, but the damage was done, and it reinforced the idea that Koestler himself was an anti-Semite – a bitter irony in the circumstances.

Statue of Arthur Koestler in Budapest. Photo: Istvan. Source: Flickr

It seems Koestler was sometimes blinded by the causes he embraced. How did he discover and become passionate about communism?

Koestler’s first exposure to ideas about socialism and communism occurred at the end of World War One, when Count Károlyi led a popular social-democratic uprising in Hungary, which was later followed by a communist dictatorship led by Béla Kun. Koestler, still a schoolboy, retained fond memories of Karolyi’s government and was open-minded about Kun, especially after Kun was chased from power and replaced by the anti-Semitic regime of Admiral Horthy, causing Koestler’s family to flee to Austria.

His next exposure came in Berlin at the end of 1931, when the rise of the Nazi party, with its concomitant anti-Semitism, and the feebleness of Germany’s conservative government drove him into the arms of the communists. In the summer of 1932 he resigned from his position as science editor at a liberal newspaper and joined a Communist Party cell, churning out anti-fascist propaganda pamphlets and joining in raids led by an unofficial communist militia. In July that year he travelled to the Soviet Union to write a book about the astounding achievements of the Soviet proletariat, White Nights and Red Days, which was published in German in the Ukraine.

He spent a year and a half in the Soviet Union before moving to Paris to take part in a Soviet-financed, anti-fascist propaganda organization led by the noted German communist leader, Willi Münzenberg. After making three clandestine visits to Spain during the Spanish Civil War, during the last of which he was jailed for four months by Francoist forces and led to believe he would receive the death sentence, he published Spanish Testament, which was translated from German into several other languages and first made his reputation as a writer.

One of the key moments in his life was this imprisonment during the Spanish Civil War. What did that experience mean for Koestler?

Well, the exact nature of the charges against him have never been discovered, but he was under the impression he would be sentenced to death as a spy, since he had worked as a newspaper correspondent without revealing his membership of the Communist Party. It was a cathartic experience for him, and the first and better half of Spanish Testament consisted of a detailed account of his months in solitary confinement, which he later revised and published as a separate book, Dialogue with Death, a book that Sartre, Camus and de Beauvoir, among others, came to regard as a classic of existentialism. In it, Koestler confronted the meaning of life and the mysteries of death, applying a moral measure to his and others’ actions that became the touchstone of all his best work to come. He concluded, among other things, that in their contempt for individual freedom and their willingness to take human life, fascism and communism were much alike, a truly revolutionary conclusion for a political revolutionary at the time and one that he was reluctant to accept at first.

Back in Paris, after finishing Spanish Testament, he resolved to resign from the Communist Party and sent a letter to the German branch of the party in exile to announce his decision, while asking its leaders to keep his resignation secret, since he didn’t wish ‘to harm the Soviet Union’. He then wrote a novel based on the life of Spartacus, The Gladiators, in which he tried to determine why Spartacus’s revolt had failed, and concluded it was because Spartacus hadn’t been ruthless enough and had refused to put ends before means. It was, perhaps, a last effort to restore his revolutionary faith, but it was in vain, not least because Koestler agreed with Spartacus’s moral scruples in holding back.

Koestler owes part of his fame to Darkness at Noon, a book which delivered a devastating blow to communism. The genesis and what happened to the book is fascinating.

Yes, and it’s far too long to summarize in an interview. I will try to suggest a few aspects. As is well known, the novel is essentially the story of a famous Soviet party leader called Rubashov, who is arrested, brought to confess his complicity in unbelievable crimes and sentenced to death. Koestler had first heard of the Soviet show trials of its leaders while in Spain, and later connected them with his conclusions about communism’s propensity to swallow its own children. Meanwhile in Paris, he met a former childhood friend, Eva Striker, who had been imprisoned in the Soviet Union as a suspected German spy, and released as a result of the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact of 1939. She described to Koestler her experiences of solitary confinement in a Soviet jail that bore astonishing similarities to his own in a fascist one, which confirmed his earlier thinking. Many of Eva’s experiences became the basis of his depiction of Rubashov’s imprisonment, and although Rubashov’s personality was loosely based on that of a real-life Soviet minister, Nikolai Bukharin, who had been tried and sentenced to death, Koestler also took his former self as a model, pronouncing his guilt as a one-time Communist believer. In this regard, the novel was heavily influenced by Koestler’s reading of Dostoevsky. The interrogations of Rubashov described in the novel were reminiscent of Raskolnikov’s in Crime and Punishment, imparting a psychological depth and moral urgency to the book that has captivated readers to this day.

When the novel first appeared in England in 1940, however, it was quickly forgotten in the heat of World War Two, but when it was republished in 1945, just as the Cold War was about to begin, it became a sensation, and in 1946 was credited with helping to ensure the defeat of the French Communist Party in the French general elections that year. The book had an influence second only to Orwell’s 1984, and stayed on the best seller lists of many countries for several decades. It secured Koestler’s reputation, made him a rich man, is still in print, and is regularly judged as one of the best novels of the twentieth century.

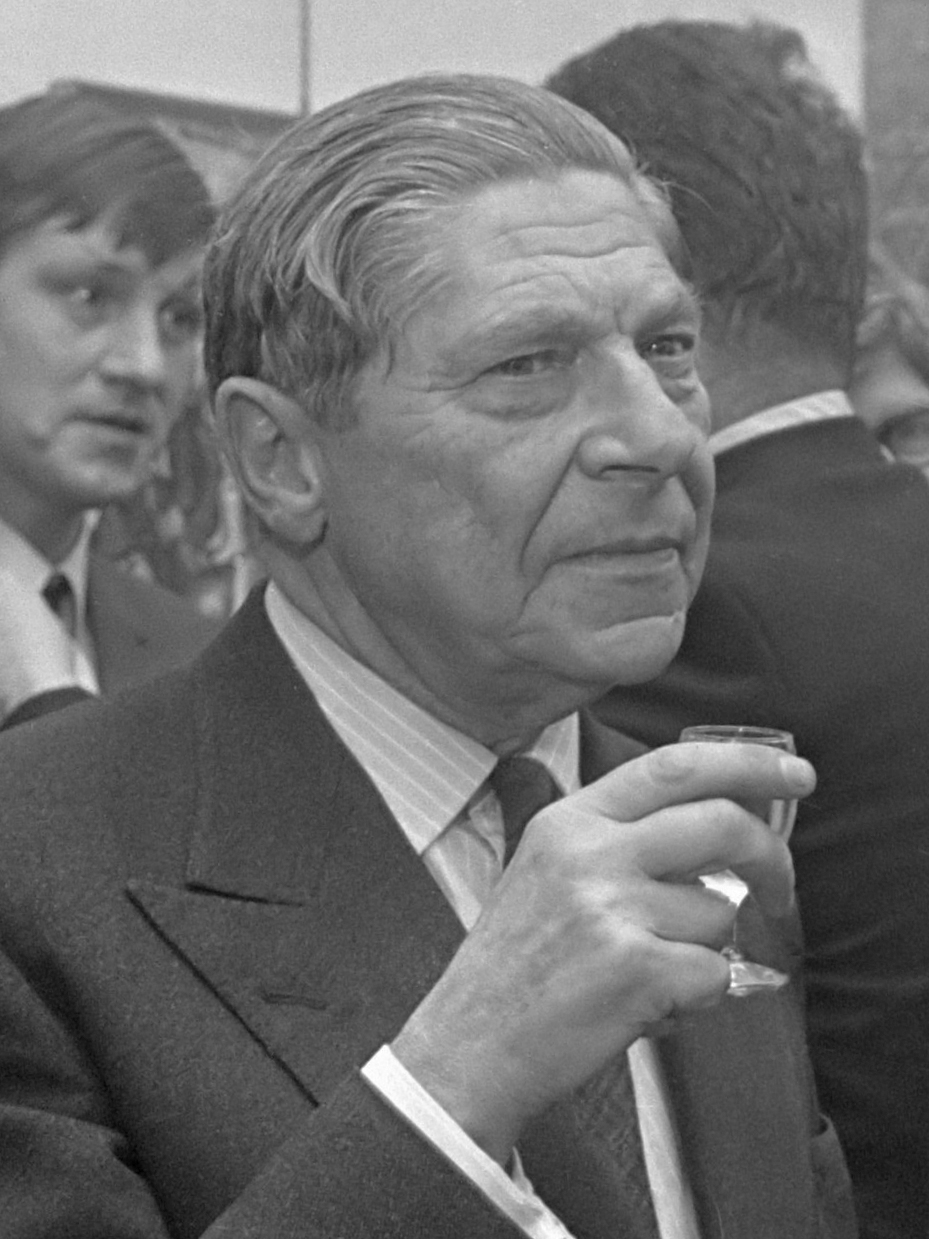

Arthur Koestler in 1969. Source: WikiMedia

Koestler was a man who caused permanent uneasiness. He took up many causes enthusiastically, and attacked some of them with a passion. After his rejection of communism, he seemed to be a man without a party, in a no man’s land, subjected to ferocious attacks. To the left, he was an apostate, someone who had sold out to the right; to the right, he was still a man of the left. Was there any truth in these charges? Why did he provoke those reactions?

Truth in the charge of selling out? No, no truth. Of holding views shared in part by the right and in part by the left, yes, plenty of truth. Koestler endured the fate of any prominent figure who proclaims his independence of parties and groups and hews to a path of his own choosing, but in his case his choices were complicated and resented for the very vehemence with which he proclaimed and defended them. They were also attacked, because politics was the ground on which Koestler chose to define them. Thus he was an implacable anti-communist in politics, which was welcome to most opinion makers on the right and made the left suspicious and resentful, but he supported the welfare state, and his hostility to communism was based to a large degree on his belief that the communists had betrayed socialism, not propagated it, and was no better than fascism, which heartened the left but frightened the right.

One of Koestler’s key ideas is that the ends do not justify the means. What were the principles he defended?

He was uncharacteristically hazy about the exact nature of the principles that guided him. Basically they came down to a Jewish sense of justice and a neo-Christian ethics, and if you look at his writing, you find it shot through with imagery from both the Old and New Testaments. But although Koestler was intimately familiar with the tenets of Judaism and flirted for a while with Christianity (and toward the end of his life even dabbled in mysticism), he was secular through and through, and shied away from defining his beliefs in any systematic form. I suppose you could call him a humanist, but though he opposed the death penalty and oppression of any kind, he was no pacifist either.

What was Koestler’s relationship with Orwell?

Koestler and Orwell admired each other’s political views and writing, and almost became related soon after World War Two, when Orwell proposed marriage to Koestler’s sister-in-law, Celia Kirwan. They also planned to start a League for the Rights of Man together, but Orwell’s ill health and premature death prevented any deeper friendship from developing.

Darkness at Noon was a huge success in France, a country that had sent Koestler to a concentration camp. What was Koestler’s relation with French intellectuals?

Koestler deeply admired André Malraux and Albert Camus, and tried at one point to come closer to Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir, but politics soon got in the way. Malraux raised Koestler’s suspicions by making common cause with General de Gaulle and becoming a minister in the latter’s postwar government, while Sartre and de Beauvoir’s uncritical admiration of the Soviet Union and persistent anti-Americanism alienated him. Camus and Raymond Aron were the two French intellectuals that Koestler remained on the best terms with, and with whom he most agreed politically. He was also close to Manès Sperber, a Jewish novelist from Galicia who wrote in German, but lived most of his life in Paris.

One of the most uncomfortable aspects in Koestler is his relationship with women. A previous biography accused him of being ‘a serial rapist’, based on the accusation of Jill Craigie. You disagree with this charge.

Yes, of course I do. Jill Craigie said publicly that Koestler had raped her, so of course we have to believe it, though I wonder why such a famous feminist waited 45 years to make her accusation, when Koestler was no longer alive to defend himself. I also think that the definition of rape changed considerably between the early 1950s, when the incident was said to have occurred, and the 1990s, when Craigie made her statement. And I also believe that Koestler was drunk at the time. Nevertheless, I took the charge seriously in my work and interviewed two of the women cited by critics as having suffered at Koestler’s hands. Neither one had come anywhere near being raped. Meanwhile I interviewed numerous women, who had had affairs with Koestler and even lived with him at different times, and none of them accused Koestler of anything like rape either. In fact some refused to believe Craigie’s story at all and thought she had misremembered or made it up in her old age. That said, Koestler shared the misogyny that was common to most men of his era and did treat many women badly in his daily life, including all three of his wives and his mother, but ‘serial rapist’ is the fantasy of an ignorant biographer who was out to discredit Koestler for political reasons.

Another unsettling episode is his death: he committed suicide when he was suffering from leukaemia and Parkinson’s. His wife, Cynthia, who was 20 years younger, also committed suicide.

Unsettling, yes, and some critics were only too happy to denounce Koestler as a monster. What they didn’t know was that Cynthia’s father had also committed suicide when Cynthia was a little girl, so that there was a history of it in her own family, and that she had a large dose of masochism in her character. They also didn’t understand that by the time of his death, Koestler was so incapacitated by his illnesses that he was totally at Cynthia’s mercy. If she hadn’t wanted to commit suicide there was nothing he could have done to make her.

Koestler saw many things and saw some of them much earlier than the rest. He defined himself as a “Casanova of causes”: he denounced Nazi and Communist atrocities, opposed the death penalty and party-line mentality, defended euthanasia, criticized the quarantine of dogs, sponsored parapsychology… What were the main things that he got right?

Well, you’ve named most of them. The point about Koestler, and the feature of his character and work that is most important to me and that attracted me most is his personal and intellectual honesty. Even people who had suffered from his abrasive personality (including many women, by the way), or been the object of his political or intellectual wrath, praised his integrity. If he believed in something or someone, he believed them to the hilt; if he was deluded, he was honestly deluded; and if he changed his mind (as he often did) he changed it totally. For the most part he didn’t lie, he didn’t pretend, he didn’t cheat, he didn’t beat about the bush, and that’s what helped to make him such an uncomfortable person to be around and difficult to deal with. I think he was right about anti-Semitism, right about fascism, right about communism, right about the death penalty, right about euthanasia, right in some respects about the excesses of behaviourism and neo-Darwinism in science, and right in many of the criticisms he made of British, French, and American politics – not a bad record for a twentieth-century writer.

Is Koestler interesting in only a historical context or does he keep his relevance as an intellectual and author?

Who can tell? History is filled with writers who were forgotten after their deaths. Some get rediscovered, others not, and some don’t deserve to be rediscovered. In my biography I present Koestler in his historical and literary context, of course, and I do believe his life was exemplary and holds a message for posterity, but I also tried to create a work of literature myself, and to show the arc of Koestler’s life as a sort of nonfiction novel. Along the way I point to those works of Koestler that I think are worth preserving for their literary and intellectual qualities, and should continue to be read for their own sake. Posterity is a fickle judge, however, and I can’t possibly foretell its verdict.

Published 20 September 2017

Original in English

First published by Letras Libres 122 (in Spanish) / Eurozine (in English)

Contributed by Letras Libre © Michael Scammell / Daniel Gascón / Letras Libres / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTSubscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Bankruptcy in nineteenth-century parables of capitalism; billionaires, bankruptcy and the American obsession with money; and why the refusal to accept the end makes life worse.

Parables of violence; memories of dictatorship; perversions of memory: Ord&Bild samples contemporary Latin American literature and photography.