For many, the enduring image of China has been that of the man standing in front of a tank in Tiananmen Square in 1989. Though there have been a number of protests since then (most notably, the Falun Gong demonstrations in Beijing in 1999 and 2000), most have been small-scale and generally under-reported by the international media. However, in recent weeks a series of dramatic images have come from the northwestern Chinese city of Ürümqi (“beautiful pastureland”), where violence broke out on 5 July 2009. There was television footage of rioters beating and kicking people. Cars and buses were set on fire. Next day, long black lines of soldiers and paramilitary police patrolled the streets, which were marked with broken glass and blood.

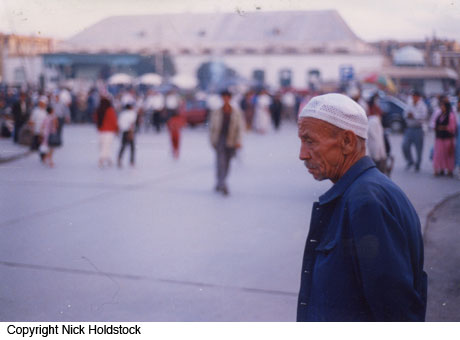

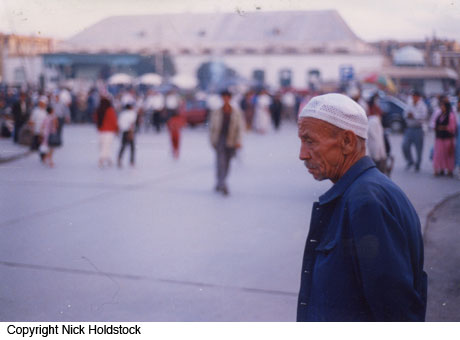

Official estimates put the number of dead at 197. Most of the victims are said to have been Han Chinese, who though they are the largest ethnic group in China, are a minority in the region. The Uighurs are the largest group in the province (hence its official title: “the Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region”). They are culturally and linguistically distinct from the Han, in that they are Sunni Muslims and speak a Turkic language closely related to Uzbek.

At present, there are two competing explanations for the violence. The Chinese government has said that they were “instigated and directed from abroad, and carried out by outlaws in the country”. They claim the unrest was orchestrated by the World Uighur Congress, led by Rebiya Kadeer, a Uighur businesswoman jailed in China, but later released into exile in the US (and who, as a result of these allegations, is now viewed by many – at least in the international community – as the closest thing the Uighurs have to a spokesperson). Wang Lequan, leader of the Xinjiang Communist Party said that the incident had exposed the WUC’s “violent, terrorist nature”. He described it as “a profound lesson in blood”.

The World Uighur Congress denies these allegations. They claim the protests were a response to recent events in Guangdong province, in the east of the country, where a man posted a message on a local website claiming six young Uighur migrant workers had raped two Han Chinese girls. This led to violence between Han and Uighur at the factory, during which two Uighurs were killed and many more injured. Rebiya Kadeer said that the “authorities failure to take any meaningful action to punish the [Han] Chinese mob for the brutal murder of Uighurs” was the real cause of the protest. The WUC claim that the violence was the result of police brutality against a peaceful student demonstration of over a thousand Uighur youths. They allege that during the crackdown many were shot or beaten to death by Chinese police, whilst others were crushed by armoured vehicles (a claim that has not been confirmed).

It is hard to reconcile such polarised versions of events, which offer two different (but equally well-worn) narratives, one of a nation attacked by terrorists, the other of an oppressed minority whose all-too-legitimate grievances are brutally suppressed. But we can imagine a protest that was initially peaceful, that grew in size and conviction until the police and army stepped in. Perhaps that was when the violence began. Or perhaps there was a stand-off, and the tension grew, until a stone was thrown, or a shot was fired, and the crowd went out of control.

This, of course, is only conjecture. What actually happened, and why, may take a long time to emerge (though it is worth mentioning that the Chinese government appear to have made fewer attempts to restrict foreign reporters’ movements than might have been expected). But whether the events of 5 July were a massacre of peaceful protestors, an orchestrated episode of violence, or something in-between, it was certainly not an event that no one had predicted. In Xinjiang there have been many protests that have been called either “riots” or “massacres”, according to different perspectives.

The largest of these took place on 5 February 1997 in Yining (aka Ghulja) – a small city on the Kazak border – when a crowd gathered to protest against unemployment, religious repression, and other grievances. After a soldier panicked and began shooting, there were numerous deaths and injuries, plus thousands of arrests. Several months later, when some of the convicted were executed, three bombs exploded on buses in Ürümqi, killing seven and injuring 67.

There were few reported incidents of protest, violent or otherwise, during the next few years (which is perhaps in itself not especially revealing, as it could either be interpreted as a sign that Uighur dissatisfaction lessened, or that the security clampdown which followed the 9/11 attacks discouraged further expressions of dissent).

The first reports of renewed conflict appeared in January 2007, when the Chinese Public Security Bureau claimed to have raided a suspected terrorist training camp in the mountains near the Pamir Plateau in southern Xinjiang. According to official sources, 18 individuals, whom Chinese State media referred to as “terrorists”, were killed and another 17 captured (however, Rafael Poch, a Spanish journalist, after investigating the incident, found no evidence that there had been such a camp).

In the run up to the 2008 Olympics, the government began publicising its efforts to ensure security. The police claimed to have raided an apartment in Ürümqi and shot dead five men who they said were planning a “holy war” against the Han. They also reported blocking an attack by three airline passengers who were planning to crash a Beijing-bound plane.

However, as in the raid on the camp in the Pamirs, there was no external confirmation of these incidents, and no group claimed responsibility. The World Uighur Congress argued that these incidents were being used to give the government an excuse to crackdown on Uighurs.

But there is little doubt that several attacks coincided with the 2008 Olympics. The first took place in Kashgar in late July, when 16 Chinese police officers were killed after two men rammed a truck into a group of police officers jogging near their barracks, then threw explosives at the police station. Although no one claimed responsibility for the attack, officials said the East Turkestan Islamic Movement (ETIM) was responsible. However, it was also suggested that the attackers had a particular grievance with the police (something that could well apply to many similar incidents in Xinjiang), and were not part of any organised group.

The next incident occurred on 4 August, two days after the start of the Olympics, when homemade explosives were thrown at a dozen government sites in Kuqa city in southern Xinjiang. A group of assailants attacked a police station, as well as government offices, supermarkets and hotels. One security guard died and 10 assailants were killed in the unrest, with police chasing down and firing at some of the attackers. Again, no one claimed responsibility for the attack, and this time the Chinese government said they did not believe the ETIM were responsible (but did not accuse anyone else).

What these different forms of protest (both violent and peaceful) have in common is that they were directed at government officials or the police. Despite mutual dislike, and widespread prejudice, Han and Uighurs have generally co-existed peacefully in Xinjiang, albeit often in virtual separation – they live in different neighbourhoods and seldom interact socially. The violence in Urumqi in July 2009 appears to be a worrying departure from this, in that many of the attacks seem to have been racially motivated, in other words directed against the Han, who had by far the most casualties. This is disputed by the World Uighur Congress, who claim that the Uighur death toll was considerably higher, but has been underreported by the government so as to make the Uighurs appear the aggressors. A third possibility, which few seem to have considered, is that the figures are accurate, but reflect demographics rather than ethnic targeting. Ürümqi is about 75 per cent Han, and 15 per cent Uighur (the rest are Hui, Kazakh and Kyrgyz). Given that most of the violence appears to have been in central, mostly Han areas, it would be surprising if the Han were not the major victims.

But whether or not the violence was racially motivated, what matters is that this is how it was perceived. This has led to greater hostility between Uighurs and Han. On 7 July a crowd of Han Chinese armed with iron bars, meat cleavers and shovels attacked Uighur neighbourhoods in Ürümqi. One man, clutching a metal bar, told the AFP news agency: “The Uighurs came to our area to smash things, now we are going to their area to beat them.” Police eventually dispersed the mob with tear gas, after there had been considerable property damage. Since then, Han and Uighur neighbourhoods have been regularly patrolled by troops; some estimate that 20 000 soldiers have been brought into the city. Unsurprisingly, many Uighurs have left Ürümqi, fearing further reprisals. Although the government are stressing that life has returned to normal, relations between Han or Uighurs are likely to remain strained.

The only positive aspect of recent events is that it has raised the profile of the region, alerting many to the possibility that Xinjiang, much like Tibet, is an area of legitimate humanitarian concern, albeit one whose situation is complicated by a persistent strand of violence.