Irena Vrkljan was born in 1930 in Belgrade into a mixed family of Austrian, Bosnian, Croatian, Slovene and Italian origin. The writer would have perhaps been remembered as a great poet were it not for her slim volume The Silk, the Shears. She was 54 years old when it was published, a kind of latecomer into popularity. That book alone, her first novel, marked not only a different kind of writing for her – poetic, autobiographical, fragmented prose – but her style and influence back home in Croatia and Yugoslavia became referential in breeding a new kind of literature written by women connected to feminism and écriture féminine. Suddenly, it was alright to write about your childhood memories, to analyse your relationship with your parents, to write about the bitter taste of love gone wrong, to be personal and emotional. Her subsequent novels Marina, or About Biography, Dora, or Autumn and many others confirmed her status and influence in terms of style and topics.

Irena published some twenty books of poems, translations, radio dramas and scripts for documentary films. In 1966 she met Benno Meyer-Wehlack, a poet and radio dramatist, and from then on she lived in Berlin. They worked together, especially on radio dramas and translations. Two of her novels are available in English: The Silk, the Shears and Marina, or About Biography (translated from Croatian by Sibelan E.S. Forrester and Celia Hawkesworth).

Irena’s relation to feminism was complex. She rejected being called a feminist – yet she was one in her life and her writing. Feminism for her meant activism and in that aspect she was an old-style leftist who believed that women were emancipated through socialism and there was no need to struggle for equal rights, for a specific kind of writing, or topics. Irena, like many others of her generation and before, made only one distinction – there was good and bad writing, regardless of sex. It is therefore a paradox that she became a model for the new kind of writing in Croatia and Yugoslavia. But a writer can hardly control her reception.

***

Irena is sitting on the old sofa in the living room. I’m facing her, in the leather armchair. There’s an ashtray on the table between us, almost full. She pulls out a long, slender cigarette, takes a couple of drags, then irritably stubs it out. ‘I’m done, I can’t go on’, she says. I know she’s saying this because her husband Benno died not long ago. She says something of the sort each time I visit. Her face looks tired, she’s not sleeping well. But her eyes are still as black and lively as ever. ‘Don’t talk like that’, I say, ‘you still have a lot to give’, although I know it won’t help. Nothing will help when the man you spent four decades with, literally every single day of four decades, has gone. And she keeps saying it, because that’s her way of letting me know it’s so hard on her that she would rather have followed him.

I think about Benno Meyer-Wehlack, a skinny, fragile-looking man with a face like a French actor’s, an editor, a writer of radio plays whom Irena had helped start writing longer pieces by him dictating to her. A stranger in Zagreb, and just as much a stranger in Berlin where he was born. Even when he had started to lose track of what was happening to him, when he asked where Irena was even though she was sitting next to him, holding his hand, he still had the same sweetness of expression that he had always had.

We’re in Zagreb. She has left her final flat in Berlin, in Pestalozzistrasse, for good. Sometimes she is seized with doubt; was it actually a good idea? All her Zagreb friends have died by now, and she is lonely, of course. The younger people around her can’t make up for what’s missing, not properly. There’s none of that ‘do you remember that evening we spent at Angel’s, or when we went down to Zlarin together,’ the way people talk when they have grown up together. The following week we make a date for lunch. I see her come in, her bearing upright, and her hair just done. As soon as she sits down at the table in the restaurant, she asks me what I think about the title Protokol jednog rastanka (Protocol of a Leave-taking), and that’s Irena: she’s started a new book and she’s already set pen to paper. Sorrow emerges, flows out and turns into superb writing. It’s not that she has freed herself of it, rather that she has found the strength to share it with others.

Library in Zagreb. Photo by Michal Balog on Unsplash.

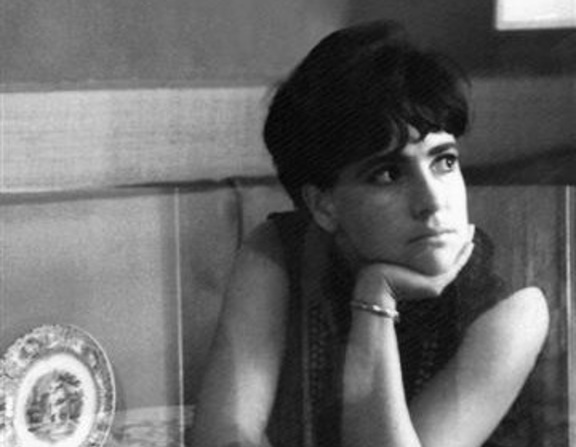

I was at the Mladost academic bookshop, the one which used to be on the corner of Preradovića Ulica (Preradović Street) and the Flower Market, and it was the spring of 1985. I was attending the launch of a book that had just come out. The book was called The Silk, The Shears, and Nenad Popović, an editor at Grafički Zavod publishers, was speaking at the event. It was mostly women who had come. Nenad was a tall man, and Irena seemed to me to be even smaller, even tinier standing next to him. With her black hair cropped short and the face of a small child that she had all her life, she spoke about the book quietly, and I thought, a little hesitantly, which surprised me. It appeared that she had been taken unawares by its tremendous success – she was not used to selling thousands of copies, to events, reviews, interviews…

It was largely my generation, twenty years and more her junior, sitting there. She could see that she had a new audience before her, but at that moment she had perhaps not yet grasped how it was different from the one she was used to, and why they found her book so appealing. In the 1990s a new understanding of the position of women in society had emerged, along with a need, or perhaps a yearning, for a different sort of prose, one which was addressed to women and spoke with a woman’s voice. This is what they discovered in Irena’s book, the first Yugoslav example of what we have grown used to calling écriture féminine. What they discovered was themselves. Even after Dora and Marina Irena very often distanced herself from ‘women’s writing’ and from feminism, refusing to call herself a feminist. Or better said, she distanced herself from lining up with any side, but not from her female readers and their devotion to her writing. From The Silk, The Shears onwards, her writing became a bridge between her times and mine whether she liked it or not. But she was happy that her books had found a wide audience.

I had read the book a few times, slim as it was, before I ever actually saw her. My Holograms Of Fear had not yet been written, and I didn’t even know that I was going to write it. It’s difficult to say what role Irena’s book played in my decision. I just know that I felt encouraged, somehow, each time I read it.

It was Holograms Of Fear that brought us together. She and Benno were living in Berlin, and only visited Zagreb now and again. I remember coming across them in the street, at the corner of Ilica and Margaretska Passage. Both of them together, because, when I think about it, I don’t believe I ever saw them apart until Benno died. She was looking summery in a white skirt and a light-coloured blouse. ‘I read Holograms, and it’s good.’ I felt something between rapture and astonishment. Could it be that my favourite author was saying this? I found out later that when she liked something she only ever said, ‘It’s good’. She did not make lengthy introductions or scatter compliments. In fact, she disliked polite conversation. She only once said anything more to me, and that was when I published The Invisible Woman. She told me I could simply stop writing now, because – it was perfect. Although this meant a great deal to me, I knew that she was not going too far. Better to put it down to her being in a passing good mood about something else, I thought.

Soon after this meeting in the street, the German publishers Rohwolt decided to publish a translation of Holograms of Fear. Nenad Popović suggested Irena and Benno to them as translators, maybe because of stylistic similarities, at least in part. The Holograms were published in their outstandingly poetic German translation in 1989, with the title of Das Prinzip Sehnsucht (The Desire Principle), something we discussed at length. Talking about other books and translations, not merely linguistic but cultural, she explained to me why they had had to change the title. Germans don’t like fear in their titles, she said. I was to recall those words later, when the German publishers Aufbau altered the name of my novel Mileva Einstein, teorija tuge (Mileva Einstein, a Theory of Sorrow), changing ‘sorrow’ into Einsamkeit, or loneliness. Germans don’t like having sorrow in their titles, either.

We bonded over these conversations, and finally, when the book was published at last, we were still talking, a conversation that continued for the next thirty years.

Phone calls were expensive and we made international calls only when we needed to. But letters, the ones in envelopes with stamps, making their slow journeys by train, slowly fell out of fashion. But the book in Germany and my work as a journalist meant that we met in Berlin.

They were still living in Mommsenstrasse, in an attic flat, the same one where Benno’s parents lived until killing themselves together in 1954. Surrounded by books and many, many artworks – by painters such as Miljenko Stančić, Karlo Sirovi, Edo Murtić, Vlado Kristl, Đuro Seder and Ivan Picelj – Irena lived in between languages, in the fault zone between Croatian and German. I understood her life, a constant interpretation of Zagreb to Berlin and Berlin to Zagreb, better when we were in one another’s company, drinking wine, sitting with them and their friends, the Yugoslav writer Bora Čosić, the Chilean artists Claudio Lange and Ingrid Lange, the philosophers Susan Neiman and Eva Meyer, and others. She would automatically translate our conversation for Benno while they were together, so that he could join in too. She did this with such ease that the conversation flowed without a hitch.

Her own writing flourished in that zone. She wrote everything: radio plays, screenplays and detective stories, her vital autobiographical novels, and of course, poetry. She often translated them into Croatian herself. But she never reached a wider audience in Germany, the print runs of her books were not large, her work went relatively unnoticed, and her writings were rarely translated into other languages. She, with her analytical turn of mind, was well aware of the reasons. It was not without bitterness that she concluded that books from our part of Europe would not succeed and would fail to draw the attention of the critics in the West unless they had exotic subjects. There was little opportunity for contemporary, thoughtful and highly supple prose like hers, delicate and fine, dealing with the identities of urban women. The Germans believed that they had their own such authors, but they were mistaken.

We saw one another a lot during the war because I went to conferences and discussions, book launches and peace initiatives, like other writers from the conflict zones who needed such an excuse to meet up. Irena would arrive (with Benno), she would speak and translate, she would socialize, and she made everyone feel better. Her critical instincts and leftist outlook always put her on the side of the victims. Irena, like many others, helped refugees, read, spoke, and gave all she could at the Centre for Southeastern Europe, a space that had been founded and was run by Bosa Schedlich, a translator and a much-respected activist for integration. There wasn’t enough room in writing for all their traumas. And the traumas were overwhelming; they changed everyone who came into contact with those people. Sometimes people just have to take refuge in writing, and so Irena, like Marina Tsvetaeva, ‘settled completely into [her] notebook’.

We soon became neighbours. My husband and I, living on the yearly grant that he received from the DAAD (German Academic Exchange Service) and that I would too, soon enough, and moved in just around the corner, at the junction of her street and Schlüterstraße. We saw one another every day, walking around Charlottenburg or at a little Italian restaurant on the Ku’damm where we ate Mediterranean seafood stew in a search for the comforts of nostalgia. She and Benno had already moved to the first floor of the same building because they could no longer climb the stairs to the top. And when we once more moved, on my grant, to Uhlandstrasse, they were in their final flat in Berlin, a little further away on Pestalozzistrasse. There too we met in an Italian restaurant and carried on talking like before. Or almost as before, since Benno’s illness had already begun to restrict what he could do. He was forgetting words more and more often now. He could no longer remember how to say ‘salt-cellar’ or ‘window’. He would sit at the table and talk quite normally, to all appearances, except that his words were utterly disjointed. He began to develop high blood pressure.

During the evenings at Bora Ćosić and Lidija Klasić’s place, where we were frequent guests, she kept watch over Benno, making sure he didn’t eat or drink anything that might cause him problems. He couldn’t understand why and became upset and teasy, like a child. He was slipping away, and Irena knew that. She did all she could to keep them together, for as long as possible.

In Zagreb, too, she had to move to a new flat, from Klaića Street to Čanića Street. She moved into emptiness. She was left to comfort herself by tidying things up. She loved putting his remnants in order and took pleasure in translations of his diaries, published in Croatia as Hodanje, cěžnje (Walking, Yearning) and his novels Schlattenschammes … oder Berlin am Meer (Schlatenschammes, or Berlin-by-the-Sea) and Ernestine geht (Ernestine Leaves). The writing is like the man, gentle and all about fine observation and emotions. ‘He was a very good man and very kind to me,’ she told me. ‘It’s not right to grow old together unless you are kind to one another.’ This was the lesson she taught me as I left her that day, not a literary one but one about life.

And in those six years after Benno she published Koračam kroz sobu (I am Walking Through a Room), Protokol jednog rastanka and Pjesme, nepjesme (Poems, Unpoems). She, who always wanted to follow him, wrote and wrote and would not allow herself to go until she stopped. Her book containing poems her contemporaries had written to her should be published very soon.

The last photograph I took of her was at lunch, in Draško’s Restaurant in Frankopanska Street, where we liked to meet for the good home cuisine. She is smiling, yet her eyes are already sad. And that too is how I left her that last time, on the same old sofa in her flat, with a cigarette in her hand. And that is how she will remain, because now she has finally followed Benno. I have no wish to balance the gains and the losses. I am at peace, her writing has left its mark on me, just as she wrote to me in a letter, or perhaps it was a poem, not long ago.