Israel has authorized a full military takeover of Gaza exactly twenty years after declaring it had ‘left’ the Strip. Disengagement failed because it was never designed to succeed – least of all on Palestinian terms.

Israel has imposed different forms of settler colonialism across the map of historic Palestine, but nothing can be taken for granted. The refugee camp is itself a spatialization of a political demand, a space of waiting for an eventual return.

I could not locate the entrance of al ‘Arub refugee camp, where I grew up. The settlement was to my right. Driving on the main carriageway, shared between the Israeli settlers and Palestinians, I expected to get to the camp’s entrance without any turns in the road. This was the map I had known. To my surprise, the carriageway took an elevation, as if one was suddenly driving towards the sky. It then cut into the hill to the south of the camp. There was a new right turn, marked by a red sign in Arabic and Hebrew, clearly declaring this territory as Palestinian and warning Israeli settlers against entering it. After a roundabout, I got to the entrance of the camp, where an Israeli checkpoint was in place. My house is the first in the camp – so near the checkpoint that I can eavesdrop on the soldiers’ conversations and music.

This is the 60-Route, a 146-mile road running from al Nasira (Nazareth) in northern historic Palestine (today’s Israel) all the way to Beer Saba’ (what Israel calls Beersheba) to the south. The road stretches from the north to the south because of historic/continuous dispossession, restricting Palestinians’ right to movement. Changing the fabric of life around al ‘Arub – as in the unexpected rerouting of the road – is part of a wider Israeli project that aims to better connect Tel Aviv and Jerusalem to Jerusalem’s surrounding settlements, and to the settlements in southern West Bank. The project unfolds in a particular historical conjuncture, defined by the intensified privatisation of the Israeli economy since 1985, the introduction of the self-ruling Palestinian Authority in 1993, and the continuing fragmentation of Palestinian geography and polity.1

Despite an increasing reliance on capital for the control, management and elimination of the Palestinian population, colonial relations remain the main constitutive driving force. The dispossession of Palestinians takes forms that may either directly exploit or contradict capitalist relations, but the unfolding of such relations always happens against the backdrop of what Glen Coulthard calls the ‘inherited background field’ of colonial relations.2 This raises a number of questions about how we understand the frictions and mediations between the different levels of a social formation: between a privatising market and a settler colonial road; a Zionist ideology and a settler colonial state – or indeed a consumerist, indebted subjectivity and a colonised society.

I came of age at a time when taking loans, purchasing private cars and aspiring to move to ‘the city’ (i.e. Ramallah) were becoming a norm in the West Bank This was capital making a larger claim on defining the horizon of possibilities for colonised Palestinian subjects. This was capital unfolding alongside patterned axes of difference: what capital is making available to you is eclipsed by structured patterns informed by gender, race, class and nationality. If capital is increasingly playing a primary role in Palestine and across the world, how do we make sense of its relations to settler colonialism and its mediation through those axes of difference? This is the question that brought me to Stuart Hall and his writings.

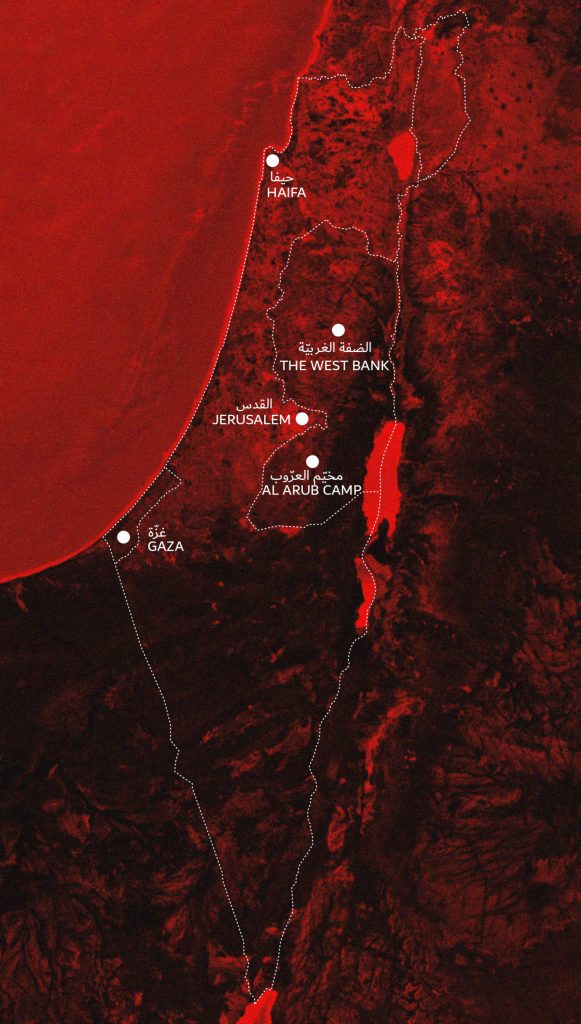

Figure 1. Map of historic Palestine, showing the ’48 territories and the ’67 territories. Map designed by Palestinian musician and architect, Haya Zaatry, 2023.

Settler colonialism is a complex set of relations, practices and processes that get condensed into durable yet historically contingent institutions, eliminatory spaces and ideologies. It seeks to implant a settler way of life in place of the indigenous. As Wolfe argues, settler colonies are ‘premised on displacing indigenes from (or replacing them on) the land’.3 In his writing on settler colonialism, Coulthard shows how, in its economic reductionism and developmentalism, orthodox Marxism fails to consider the constitutive and continuous role of dispossession, particularly in settler colonial contexts. This contradicts Marx’s idea of ‘primitive accumulation’, which relegates violence to a bygone historical moment.4 Given the continuous and continuing use of brute violence by settler colonial states for the dispossession of indigenous people, including Israel’s latest genocide in Gaza and contemporary attempts by the United States to dispossess indigenous communities in Standing Rock, it is clearly a political and conceptual necessity to understand dispossession as a constitutive part of both contemporary and historical patterns of capital accumulation.

Thinking about space is a generative entry point into understanding the ‘concrete historical work’ that settler colonialism achieves in each spatio-historical conjuncture: ‘as a set of economic, political and ideological practices, of a distinctive kind, concretely articulated with other practices in a social formation’.5 Doreen Massey, mentioning her regular lift to work with Stuart Hall, proposes we understand space as produced by interrelations.6 Space is not fixed. ‘You are not just travelling across space; you are altering it a little, moving it on, producing it. The relations that constitute it are being reproduced in an always slightly altered form.’7

The settler road is concrete, a material and spatial manifestation made possible through practices (stealing the land from the indigenous, building the road and surveilling it with military watch towers), institutions (the military and supreme courts, municipality and corporate bodies), and processes (capitalism and colonialism). The settler state and the businesses get to decide how and where the road passes through. But that does not mean they are the only ones producing that space; such a view, as Massey suggests, ‘deadens space’.8 I too – a subject of military occupation and an afterlife of refugees displaced in 1948 – produce the road as a space, by passing on and living alongside it.

Not only is space made up of multiple intersecting relations: it also unfolds within an open system and on an unequal terrain. The result is neither total incorporation of the native Palestinians into settler colonial spaces, nor a total reclaiming of space. It is a ‘continuous and necessarily uneven and unequal struggle’.9 This is a map ‘without guarantees’, one that sees processes and things as constituted by relations; relations as historically contingent and particular; and relations as prone to rupture and transformation.I am here drawing on Stuart Hall’s powerful 1986 essay ‘The Problem of Ideology – Marxism without guarantees’, where he criticises orthodox Marxism’s tendency to presume a necessary correspondence between the different levels of social formations. He argues that presuming a functionalist understanding whereby, for example, those occupying a working-class subjectivity are presumed to be revolutionary by virtue of that subjectivity leads to a determinism that deadens politics. There are no guarantees that such a subjectivity will be revolutionary for that depends on actual, concrete struggles.10 This is a map without guarantees, where settler colonialism may, one day, cease to exist.

In this essay, I write a theoretical diary, informed by Stuart Hall’s writings, that traverses the refugee camp, the village and the city. It is part of a wider project that seeks to animate Stuart Hall’s thought by examining its remits and limits when thinking about settler colonialism across historic Palestine. In particular, I draw on Stuart Hall’s insistence on ‘conjunctural analysis’ to demonstrate how (1) there exist multiple Palestinian geographies; (2) how such geographies stand in relations of domination and subordination vis-à-vis one another and the Israeli state; and (3) how such geographies remain prone to rupture and transformation.

I also use countermaps designed for this essay by Palestinian architect and musician Haya Zaatry, as well as photographs I have taken of the different geographies. I use ‘’48 territories’ to refer to Palestinian territories occupied in 1948, ‘’67 territories’ to refer to the lands occupied in 1967, and ‘historic Palestine’ to refer to the entire land, engulfing both the ’48 and ’67 territories. This is not only consistent with how Palestinian communities, scholars and activists name these territories: it is integral to any attempt to understand the continuous yet differentiated logics of dispossession across historic Palestine.

In recounting the story of someone born out of place, displaced from the dominant currents of history, nothing can be taken for granted. Not least the telling of a life.

Stuart Hall, 2017.11

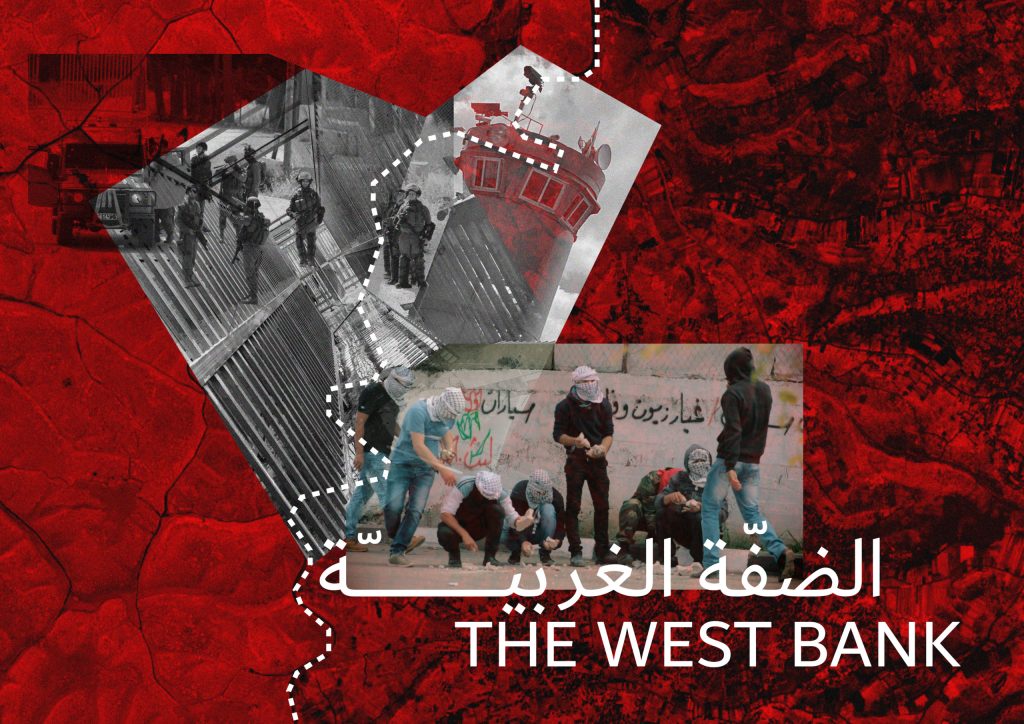

Figure 2. Countermap, showing photographs from the west bank superimposed on the 1949 green line West Bank border. Designed by Haya Zaatry, 2023.

Nothing can be taken for granted. Is not the space of the refugee camp in and of itself a spatialisation of a political demand? It is a space of waiting for an eventual return. And in that space of waiting lies the everyday politics – what Hall termed the ‘social transactions of everyday colonial life’.12 Nothing can be taken for granted when the street you live on is named after a village you have always imagined but never visited. When the entrance to the camp is controlled by checkpoints meticulously designed as life valves. When the Gush Etzion settlements lie at the hilltop, vividly lit up and ferociously surrounded by barbed wires, surveillance cameras and watch towers. Palestinian novelist Hussein Barghouthi once described the settlement as if ‘hanging from space, perhaps because of the lighting too, without touching the ground, or history, yet’.13 This is the ‘colonial sector’ as Fanon – writing on colonial Algeria – once dubbed it: ‘it is a sector of lights and paved roads, where the trash cans constantly overflow with strange and wonderful garbage, undreamed-of leftovers’.14

Figure 3. Photograph of the new 60-route extension. The bottom right shows the entrance of Al ‘Arub refugee camp. Photograph by the author.

Al ‘Arub is a refugee camp in northern Hebron in the West Bank. It houses ten thousand Palestinian refugees, mostly displaced from villages near Gaza and Hebron after the establishment of Israel in 1948. The camp is surrounded by settlements – Gush Etzion to the north, Karmei Tzur to the south, and another, recent, settler outpost to the north. To its north and northwest, the camp is fully engulfed by the 60-Route (see Figure 3), a highway built by Israel and shared – though with differentiated access – between Palestinians and the Israeli settlers.

The most recent settler outpost was imposed on top of a historic hospital (colloquially referred to as al-Lambie Hospital, see Figure 4), built under Jordanian rule in the 1950s. In 2015, settlers moved into the building, kicking out the Palestinian family guarding it. They have since turned it into a wedding hall, which was officially conjoined with the Gush Etzion Municipality in 2016. Stealing this building led to the gradual seizure of the land surrounding it. The road, cutting close to the hospital before ascending towards the southern hill, continues this erasure; its completion was contingent on the seizure of Palestinian lands. Roads, as Omar Jabary Salamanca argues, are part of a wider project of dispossession that serves the long-term domination of the settlers.15

Figure 4. Photograph of Beit el Baraka, the hospital that has been turned into a settler outpost near Al ‘Arub refugee camp. Photograph by author.

Colonial relations serve as the inherited background field within which capitalist, patriarchal and racist relations converge to create, sustain and perpetuate a settler way of life. But these relations, as well as their convergence, are historically contingent. This is the ‘historical premise’ that Hall always insisted on: the forms of historical relations and their convergence with one another cannot be schematised a priori, for they are historically and geographically specific.16 And, as Gillian Hart comments, ‘this, in turn, requires attention to class-race (and other) articulations forged through situated practices in the multiple arenas of daily life’.17 So, what is the historical context in which dispossession takes place around a refugee camp in the West Bank in the current moment?

The current historical conjuncture in the West Bank is defined by a particular articulation between colonial and capitalist modes of accumulation, crosscut by gender, race and class. In 1985, the Israeli state issued the Economic Stabilisation Plan, which effectively neoliberalised the Israeli economy. The plan led to further intensified privatisation of publicly-owned lands and companies, and further plugging of the Israeli economy into global circuits of capital.18 In 1993, the Oslo Accords were signed between the Palestinian Liberation Organisation and the Israeli state, officially establishing the Palestinian Authority as a self-ruling government in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip. The Accords were followed by the Protocol on Economic Relations (also called the Paris Protocol) in 1994, which integrated the Palestinian economy into Israel’s through a ‘customs union’.

Not only are all entry and exit ports to and from Palestinian territory controlled by the settler state; it also controls the inflow of international aid, as well as the entire land of the West Bank (the land there is juridically categorised as areas A, B, and C, with different levels of Israeli control in each). Both the Accords and the Protocol were supposed to be temporary, pending final negotiations. However, they remain in effect today.

Through those agreements, the Palestinian economy is locked in a relation of dependency. Adam Hanieh argues that the Oslo Accords have aimed to outsource the costs of the military occupation to international aid, and to cantonise Palestinian geography.19 Writing on housing and the reconfiguration of Palestinian space in the post-Oslo conjuncture, Kareem Rabie argues that the accords became a way of managing and sustaining the inequality between the Israeli and Palestinian economies.20 The neoliberalisation of the Israeli economy and the Oslo Accords set in motion a new coupling of capital and colonial relations, whereby the former comes to play a more direct role in dispossession. That coupling is mediated through multiple levels of determination.

This brief mapping of the set of economic, political and social relations that define the post-Oslo conjuncture points to economic systems that stand within relations of domination and subordination. Writing on South Africa, Hall proposes that the inequalities between different economies imply the existence of multiple forms of political representation.21 In the post-Oslo conjuncture, there exists a hierarchy of representation that reaches the entire map of historic Palestine. Palestinians living within the ’48 territories (such as Haifa) are positioned as citizens of the Israeli state. In contrast, Palestinians living within the ’67 territories are subjects of martial and administrative law. Israeli civil law, too, as Rabie argues, is weaponised to entrench colonial hierarchies and domination.

While the Palestinian Authority was meant to operate across the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, after the 2006 Palestinian Legislative Council elections a political split occurred between Fatah (a secular, nationalist party) and Hamas (an Islamist party). Though internationally monitored, these election results were subsequently rejected by the European Union, Israel and the United States. Following the elections, Hamas came to control the Gaza Strip, while the Palestinian Authority (ruled by Fatah) came to control the West Bank.

The international delegitimisation of Palestinian electoral politics led to the further entrenched neoliberalisation of the Palestinian economy. A general aim of neoliberalism is to lower the barriers of trade and smoothen out the pathways for capital circulation while entrenching political, economic and social inequalities. But this general global phenomenon actually exists in historically determined contexts. Writing on the post-Apartheid moment in South Africa, Hart notes how the African National Congress, led by Thabo Mbeki, tried to balance the advancing of a neoliberal agenda with liberation symbols and ideas.22 The Palestinian Authority embodies a similar conundrum. It mobilises a history of armed resistance to advance a neoliberal agenda that further entrenches colonial hierarchies.

Such an agenda has nurtured a Palestinian capitalist class – and a Palestinian capitalism that exploits, rather than resists, the contradictions of the colonial reality. The Palestinian Authority, led by Mahmoud Abbas since 2005, has witnessed a noticeable harmonisation between the Authority’s structures and the Israeli settler colonial state. In effect, this has meant close security coordination with the settler state; economic cooperation that selectively benefits a Palestinian bourgeoisie while impoverishing the rest; and intensified suppression of dissent.

Fanon notes that compromise is the nationalist bourgeoisie’s attempt to reassure themselves and the colonists that they will not jeopardise previous arrangements.23 As Coulthard notes, settler colonies tend to revert to a ‘colonial politics of recognition’, which aims to incorporate – and therefore annul – indigenous demands for self-determination through legal circuits that serve only the long-term dominance of the settlers.24 The result of the compromise in the West Bank has been a hollowing-out of Palestinian institutional politics; a professionalisation of grassroots politics through NGO-isation;25 and a proliferation of consumerist and indebted subjects, enduring a military occupation while being dependent on loans. This is the impossible promise of Oslo: to consume and dream of a better life within the structural constraints of a settler colonialism intent on eliminating you from the land.

The camp in the West Bank is a constant reminder that dispossession remains active and constitutive across Palestine. That the settlement has eaten up the fabric around the refugee camp is an eloquent reminder that dispossession did not stop in 1948. But that does not mean dispossession has since then unfolded unabatedly, in the same shape and manner. The neoliberalisation of the Israeli economy, followed by the Oslo Accords, demonstrates how capital and dispossession adapt themselves to the contemporary imperatives of colonial domination’,26 ushering in new mechanisms of control, management and erasure. In the post-Oslo conjuncture, dispossession continues, but through new mechanisms, delivering a ‘transformed settler colonialism’.27 Given their contingency, such mechanisms may be transformed, subverted, resisted, worked upon or overthrown.

It’s difficult, too, to work through the question of how these pasts inhabit the historical present. Via many disjunctures – filaments which are broken, mediated, subterranean, unconscious – the dislocated presence of this history militates against our understanding of our own historical moment.

Stuart Hall 2017.28

Figure 5. Visiting al Safiriyya. The photograph shows one of the two abandoned buildings remaining atop al Safiriyya village. Photograph by author.

The Israeli state was established through an event of dispossession that turned more than 750,000 Palestinians into refugees. At that time, the newly established state organised committees, institutions and processes to turn this event into a sustainable juridical, political, cultural and economic formation.29 It also relied on Zionist institutions and agencies established prior to 1948, including the Histadrut (the General Organisation of Workers in Israel). Between 1948 and 1953 in particular, the state experimented with multiple ad hoc processes to institutionalise the theft of Palestinian land and property. These efforts culminated in the establishment of the Custodian of Absentee Property, a governmental agency responsible for handling stolen buildings and lands. That period also witnessed the establishment of Amidar National Housing Company in 1949 and the Development Authority in 1951.

Using Stuart Hall’s register, the bringing together of practices of dispossession into sustainable juridical institutions constitutes an act of ‘connotative condensation’.30 Settler colonialism is constituted by processes and practices that become linked in ways particular to each historical conjuncture. In the first two decades following its establishment, the settler state played a major role in organising the shape and form of these processes and practices, as well as the linkings (articulations) between them, in order to maintain a system of domination that favours the long-term development of the settler.

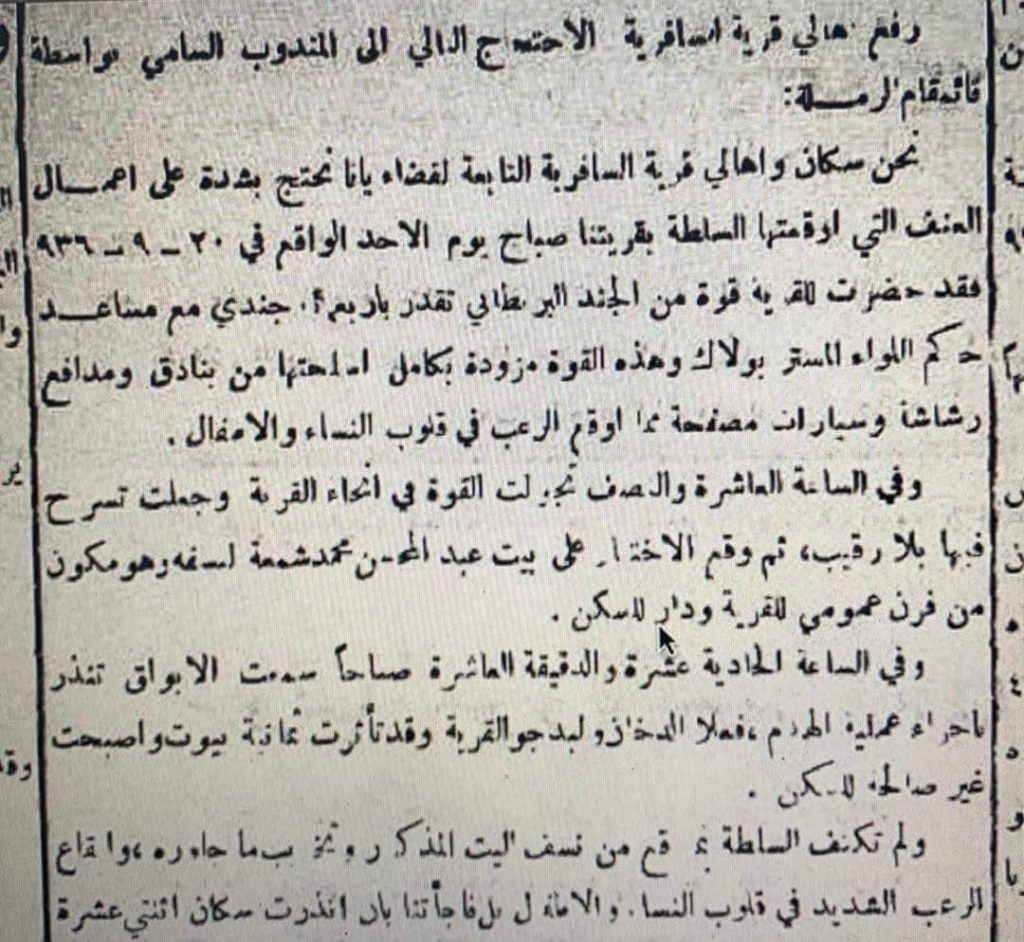

In 2018, my family and I enacted a rehearsal of return. Three generations (my grandmother, my father and I) went through an Israeli checkpoint near Bethlehem. The fragmentation of Palestinian geographies means restrictions on the right to movement for Palestinians, so that the 60-Route, for example, is lived through different maps: one for settlers and another for Palestinians. We then continued to al Safiriyya, which was once a Palestinian village ten kilometres to the east of Yafa (Jaffa). My grandparents owned a bakery here. And that bakery was demolished in 1937 by the British colonial forces as a punitive measure against the family’s participation in the Palestinian Great Revolt of 1936-39. When looking through Palestinian newspapers predating 1948, I found a call from the people of al Safiriyya in al Difa’ Newspaper, denouncing the demolition of Abdulmosen Abushama’s (my grandfather) house and bakery. If memory is ‘a means by which history is lived’ (Hall 2017, 78), it is also a means by which space is reimagined and relived.31 This was my grandmother’s first visit back to al Safiriyya since 1948.

Figure 6. A call from the people of al Safiriyya to the British high commissioner, denouncing the demolition of Abdulmohsen Abushama’s house and bakery. Al Difa’ newspaper, 23 September 1936.

Many Palestinians I know have attempted such a return: a necessary rehearsal that breaks the heart and reorients return towards the future. Return, then, becomes a constant process and practice of questioning the interlocking relations that structure dispossession, as well as weaving together the moments, acts and movements of resistance against it.

The dispossession that had occurred in al Saifiryya, alongside another 450 Palestinian villages as well as its cities, is the event that required condensation by the settler state. The theft of property, and its articulation to economic and political institutions, was meant to create the settler subject as property-owning and the native Palestinian as propertyless. When discussing juridical forms and property under slavery, Hall suggested that it was not just attitudes of racial superiority that precipitated slavery.32 Slavery, too, ‘produced those forms of juridical racism which distinguish the epoch of plantation slavery’. Again, this is an analysis that starts with looking at the ‘concrete historical work’ of a particular structure, and asking: ‘what are the specific conditions which make [a particular] form of distinction socially pertinent, historically active?’ (p236).

It was Zionist ideology – couched in the terra nullius logics of conquest that selectively repurpose secular and religious ideas to serve a particular social group of European settlers – that activated the constitutive distinction between the settler and the native. The state is a site of cohesion, the result of tendential articulations (particular, favoured, linking) between ideology, subjectivity and property. The state played the primary role in the erasure of al Safiriyya. Is not the erasure of al Safiriyya a primitive accumulation, an accumulation by dispossession, where the state and ideology (not only the economy, as Harvey might put it) play a primary role?33 As they lived through the afterlives produced by that violence, the residents in al ‘Arub refugee camp experienced violence differently in the post-Oslo historical conjuncture: violence mediated through the Israeli army as an agent of the state, the settler as an agent of Israeli civil law, and the Palestinian Authority as a native agency aimed at nurturing bourgeois interests while suppressing anti-colonial and social dissent. Settler colonialism is contingent on these historically determined practices and processes. And it is vulnerable to the rehearsals of return.

Figure 7. Burj 15. Home of Palestinian refugee Abed el Latif Kanafani. It has been turned into Israeli law offices. Photograph by Sama Haddad.

On a cold day in January 2020, we drove around the city of Haifa.34 We first went to Wadi Salib, which stands in the eastern part of the city, where there are many old homes – some neglected, others renovated – that belonged to Palestinian refugees before 1948. In al Burj neighbourhood stood the houses of Abdellatif Kanafani and Abed Elrahman El Haj (mayor of Haifa, 1870-1946). The house of the Kanafanis (Figure 7) – appropriated by the Israeli state in 1948, sold to the state-owned housing company Amidar in 1953, and in recent years sold on to four different real-estate companies – has been renovated and turned into law offices.35 The old and partially destroyed shops below the houses displayed a large poster in Hebrew by architects Ilan Pivko, showing its vision for their renovation. The old fronts would be polished and renovated, and, on top of them, large ‘modern’ residential places would be built. These developments are part of market-led, municipality-facilitated efforts to reshape what remains of Haifa.

Wadi Salib is a site of layered dispossession. The Israeli state forcibly drove out the Palestinian residents of the neighbourhood in 1948. All the remaining Palestinians in Haifa were relocated to Wadi Nisnas neighbourhood and placed under strict military rule, while arriving Arab Jews were placed in Palestinians’ now vacant homes. The Arab Jews were racialised as natural proprietors of these places, as they were presumed to come from similar ‘mellah’ living conditions in Morocco.36 The racial hierarchy of the newly-established Israeli state was already being woven and mediated through space. In 1959, there was an Arab Jewish rebellion in reaction to the unbearable living conditions in the neighbourhood, which led to its evacuation.37

Contemporary attempts by the Haifa municipality and Israeli and international capital to refashion the neighbourhood as authentic real estate not only rely on but also perpetuate this layering of dispossession: firstly of the Palestinians, and secondly of the Arab Jews. The tendential articulation solidified in 1948, which favoured the white European settler as the archetypical proprietor of stolen Palestinian property, was accompanied by a sedimentation of other articulations, including the dispossession of the Palestinians and the racialisation and precaritisation of the Arab Jews. The gradual, neoliberal refashioning of space within the ’48 territories, including Haifa, since 1985, has occurred within the parameters of this inherited background field of colonial relations.

As Elya Lucy Milner has shown in her discussion of the Arab Jewish Giv’at-Amal neighbourhood, built in 1948 on top of the depopulated Palestinian village of Jamassin, private capital feeds on this layering of dispossession by completely denying Palestinian claims to the land as well as contesting the Arab Jewish settlers’ precarious ownership rights.38 Though included in the settler society as Jews whose religious lineage entitles them to a ‘right of return’ to stolen Palestinian lands (as per the 1950 Law of Return), Arab Jews are racialised as lesser settlers, whose entitlement to the land is questioned.

It is no surprise, then, that in 1986 the land of Jamassin-Giv’at Amal – along with the right to evict its Arab Jewish residents – was sold to a number of private entrepreneurs. Some of the Arab Jewish settlers, Milner tells us, have weaponised their settler subjectivity and their participation in the dispossession of the Palestinians in order to substantiate their claim to the land. Capital, and its coupling with the colonial relations, constitutes historical relations that are crosscut by race.

If, following Doreen Massey and Max Ajl and colleagues, we view the city as a condensed vantage point into articulated practices and processes (i.e. not a thing that precedes the process), the city can be understood as one socio-spatial form amongst many other possible and imagined ones.39 Furthermore, the city of Haifa can be seen as a constellation of power relations determined by the particular historical conjuncture under examination here. In the post-Oslo conjuncture, Palestinians living in Haifa face a new coupling of capital and colonial dispossession, crosscut by race, gender and class, whereby capital takes a more primary role while feeding on the raw contradictions unleashed by the colonial relations. Although Palestinians within the ’48 territories are included as citizen subjects of the state, that inclusion is structured as an exclusion that remains reliant on a layering of dispossession: it is made possible by the denial the Palestinian right to self-determination across the map.

I write at a time of turmoil and intensified, genocidal, violence. Thus far, Israel has killed more than thirty-five thousand Palestinians in the Gaza Strip. Israeli airstrikes have targeted hospitals and schools, erasing entire neighbourhoods. Entire Palestinian families have been wiped out of the civil registry. Israeli officials have flagged up the idea of the permanent displacement of Gazans to the Sinai desert.

While western media outlets and political establishments rush to obscure this as rational self-defence, a historicist and geographic approach to Gaza shows that Israel’s targeting of the Strip is a brutal manifestation of the settler colonial intent to eliminate native Palestinians. That same intent is expressed in the settlers and military watch towers in the West Bank, and targets what remains of Palestinian urbanity in Haifa through urban renewal projects. In Gaza, this intent has taken the shape of a brutal siege that has been imposed since 2007, followed by a series of wars that aim at de-developing the Strip, and now by a full-blown genocide.40 When viewed from al ‘Arub refugee camp, al Safiriyya, Jamassin and Haifa, it becomes clear that the Gaza Strip is facing another layering of dispossession. Gaza lies at the bottom of a hierarchy of life and violence that Israel imposes across the map of historic Palestine.

Figure 8. Countermap showing photographs from the 2023 war on Gaza superimposed on the Gaza Strip. Designed by Haya Zaatry, 2023.

Settler colonialism is a whole constituted by its historically determined parts; and the parts are, in turn, constituted by a historically determined whole.41 And the same mix of contingency and complexity applies to capitalism. The local, such as al ‘Arub camp, is not a simple manifestation that reflects an all-encompassing global process. It is a nodal point of articulation – specific, differentiated, contingent. This is Hall’s Marxism without guarantees: there is no guaranteed correspondence or non-correspondence between the different levels of a social formation; structures do not pre-date relations; and the global processes of capitalist accumulation, and of Israeli settler colonialism, take specific forms, in differentiated iterations, that rely on the relations that constitute each spatio-historical conjuncture.

As such processes unfold across the map of Palestine, they take particular shapes and forms, resulting in a number of different, historically determined, settler colonial paradigms: the military occupation in the West Bank; the besiegement, de-development and targeting of human life in the Gaza Strip; the administrative law in Jerusalem; and the inclusion through exclusion in the ’48 territories. This is a map without guarantees: there is neither a guarantee that settler colonialism’s intent to eliminate the Palestinians will succeed, nor a guarantee that Palestinians will take up a particular form of resistance.

This is a map without guarantees: it is a map that takes very seriously the structural constraints shaping fragmented Palestinian geographies, but it is also one that animates the pressures that Palestinian practices and modes of resistance exert on these historical forces.

This is a map without guarantees, where settler colonialism may, one day, cease to exist.

A map without guarantees, where rehearsals of return will, one day, cease to be rehearsals.

This essay was the winner of the inaugural Stuart Hall Essay Prize, a project initiated by the Stuart Hall Foundation. The award was presented at the 7th Annual Stuart Hall Public Conversation in March 2024, also organised by the Trust. We thank the trust for permission to publish this sightly edited version: https://www.stuarthallfoundation.org/.

See Adam Hanieh, ‘From State-Led Growth to Globalization: The Evolution of Israeli Capitalism’, Journal of Palestine Studies, Vol 32 No 4, 2003, pp5-21: https://doi.org/10.1525/jps.2003.32.4.5; and Lineages of Revolt: Issues of Contemporary Capitalism in the Middle East, Chicago, Illinois, Haymarket Books 2013; Kareem Rabi, Palestine Is Throwing a Party and the Whole World Is Invited: Capital and State Building in the West Bank (Electronic Resource), E-Duke Books Scholarly Collection, Durham, Duke University Press 2021: https://ezproxy-prd.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/login?url=http://dx.doi.org/10.1215/9781478021407; Omar Jabary Salamanca, Mezna Qato, Kareem Rabie and Sobhi Samour, ‘Past Is Present: Settler Colonialism in Palestine’, Settler Colonial Studies Vol 2 No 1, 2012, pp1-8: https://doi.org/10.1080/2201473X.2012.10648823.

Glen Sean Coulthard, Red Skin, White Masks: Rejecting the Colonial Politics of Recognition, Indigenous Americas, Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press 2014, p15.

Patrick Wolfe, ‘Settler Colonialism and the Elimination of the Native’, Journal of Genocide Research, Vol 8 No 4, 2006, pp387-409, p387: https://doi.org/10.1080/14623520601056240. They do so through positive (e.g. recognition and assimilation) and negative (e.g. genocide and disenfranchisement) mechanisms.

See Michael Levien, ‘From Primitive Accumulation to Regimes of Dispossession: Six Theses on India’s Land Question’, Economic and Political Weekly, Vol 50 No 22, 2015, pp146-57.

Stuart Hall, ‘Race, Articulation and Societies Structured in Dominance’ [1980], republished in Stuart Hall, Selected Writings on Race and Difference, edited by Paul Gilroy and Ruth Wilson Gilmore, Duke University Press 2021, p236: https://chooser.crossref.org/?doi=10.1215%2F9781478021223-014.

Doreen Massey, For Space, London, Sage 2005, p225.

Ibid. p226.

Doreen Massey, Space, Place and Gender, Polity 1994, p40.

Hall, Selected Writings on Race and Difference, p354.

Stuart Hall, ‘The Problem of Ideology – Marxism without Guarantees’, The Journal of Communication Inquiry, Vol 10 No 2, pp28-44: https://doi.org/10.1177/019685998601000203.

Stuart Hall, Familiar Stranger: A Life between Two Islands, London, Allen Lane 2017, p95.

Hall, Familiar Stranger, p93.

Hussein Barghouthi, Among the Almond Trees: A Palestinian Memoir. Translated by Ibrahim Muhawi With an Introduction by Ibrahim Muhawi, The Arab List, Seagull Books 2022: https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/distributed/A/bo124470392.html. Translated from Arabic by the author.

Frantz Fanon, The Wretched of the Earth, translated from the French by Richard Philcox, with Commentary by Jean-Paul Sartre and Homi K. Bhabha, New York, Grove Press 2004, p4.

Omar Jabary Salamanca, ‘Assembling the Fabric of Life: When Settler Colonialism Becomes Development’, Journal of Palestine Studies, Vol 45 No 4, 2020, pp64-80: https://doi.org/10.1525/jps.2016.45.4.64.

Hall, ‘Race, Articulation and Societies Structured in Dominance’, p217.

Gillian Patricia Hart, Disabling Globalization: Places of Power in Post-Apartheid South Africa, Berkeley, University of California Press 2002, p31.

See Yara Sa’di-Ibraheem, ‘Privatizing the Production of Settler Colonial Landscapes: “Authenticity” and Imaginative Geography in Wadi Al-Salib, Haifa’, Environment and Planning. C, Politics and Space, Vol 39 No 4, 2021, pp686-704: https://doi.org/10.1177/2399654420946757; Nadeem. Karkabi, ‘How and Why Haifa Has Become the “Palestinian Cultural Capital” in Israel’, City & Community, Vol 17 No 4, 2018, pp1168-1188: https://doi.org/10.1111/cico.12341.

Hanieh, ‘From State-Led Growth to Globalization, p18 (see note 1).

Rabie, Palestine Is Throwing a Party (see note 1).

Hall, ‘Race, Articulation and Societies Structured in Dominance’, p229.

Hart, Disabling Globalization, p33.

Fanon The Wretched of the Earth, p24 (see note 14).

Coulthard, Red Skin, White Masks (see note 2).

See Rema Hammami, ‘NGOs: The Professionalisation of Politics’, Race & Class, Vol 37 No 2, 1995, pp51-63: https://doi.org/10.1177/030639689503700200.

Brenna Bhandar, Colonial Lives of Property: Law, Land, and Racial Regimes of Ownership, Global and Insurgent Legalities, Durham North Carolina, Duke University Press 2018, p14.

Here, I am extending Stuart Hall’s concept of ‘transformed racisms’ (see Hall, ‘Race, Articulation and Societies Structured in Dominance’). I explore this in greater length in an article titled ‘Articulations: a relational comparison of settler colonial dispossession and cultural practices in Haifa and Ramallah’ submitted to the Annals of the American Association of Geographers Journal.

Hall, Familiar Stranger, p71.

See Shira Robinson, Citizen Strangers: Palestinians and the Birth of Israel’s Liberal Settler State, Stanford Studies in Middle Eastern and Islamic Societies and Cultures, Stanford, California, Stanford University Press 2013.

Hall, ‘Race, Articulation and Societies Structured in Dominance’, p232.

Hall, Familiar Stranger, p78.

Hall, ‘Race, Articulation and Societies Structured in Dominance’, p235.

David Harvey, ‘The “New” Imperialism: Accumulation by Dispossession’, Socialist Register, 40, 2004.

That day, I was taken on a tour around Haifa by Palestinian geographer Yara Sa’di-Ibraheem and her partner, Hisham, whom I would like to thank for their knowledge and time.

Sa’di-Ibraheem, ‘Privatizing the Production of Settler Colonial Landscapes, p698 (see note 18).

Yfaat Weiss, A Confiscated Memory: Wadi Salib and Haifa’s Lost Heritage, New York, Columbia University Press 2011. Mellah is an Arabic term that refers to Jewish neighbourhoods in Morocco.

Ella Shohat, On the Arab-Jew, Palestine, and Other Displacements: Selected Writings, London, Pluto Press 2017, p72.

Elya Lucy. Milner, ‘Devaluation, Erasure and Replacement: Urban Frontiers and the Reproduction of Settler Colonial Urbanism in Tel Aviv’, Environment and Planning D, Society & Space, Vol 38 No 2), pp267-86, 2020: https://doi.org/10.1177/0263775819866834.

Doreen Massey, World City, with new Preface: ‘After the Crash’, Cambridge, Polity Press [2000] 2010; and Max al Ajl, Hillary Angelo, Neil Brenner, John Friedmann, Matthew Gandy, Brendan Gleeson et al, Implosions /Explosions: Towards a Study of Planetary Urbanization, Berlin, Jovis 2015: https://doi.org/10.1515/9783868598933.

See Sara M. Roy, The Gaza Strip: The Political Economy of de-Development, Washington, DC, Institute for Palestine Atudies 1995.

See Gillian Hart, ‘Relational Comparison Revisited: Marxist Postcolonial Geographies in Practice’, Progress in Human Geography, Vol 42 No 33, 2018, pp371-94: https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132516681388.

Published 9 September 2024

Original in English

First published by Soundings 86 (2024)

Contributed by Soundings © Hashem Abushama / Stuart Hall Foundation / Soundings journal

PDF/PRINTSubscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Israel has authorized a full military takeover of Gaza exactly twenty years after declaring it had ‘left’ the Strip. Disengagement failed because it was never designed to succeed – least of all on Palestinian terms.

Gaza and the age of impunity; Islamism and leftwing anti-Zionism; dead-ends of Staatsräson; illiberal rap.