Too often, a revolutionary life appears free of tedium. Revolutionaries emerge from whatever page or screen we discover them on seemingly fully formed. Their lives unfold as a series of events that continually evidence an iron-clad political commitment to building a liveable world and securing freedom for all oppressed people. Because of this romanticized picture, the gulf between our lives and theirs expands. It is hard to imagine that they ever really existed at all – harder still to grapple with the true complexity of that existence. They remain ghosts, die righteous, too soon or vindicated.

In an effort to recover them, we begin to name the turning points: a critical speech or event that helps us trace the growth of their political concerns and aspirations. With this historical material, we piece together a political trajectory, taking into account their experiences, influences and ideas. The archive is a treasure trove. It enables us to reconstruct what we think we know about their personal lives, providing a glimpse of close friendships with other political actors and artists; it keeps us guessing. What is hidden is the bureaucracy of living: the question of how the revolutionary survived monetarily, who they loved, how they worked and the intricacies of the relationships they formed along the way.

In this way, Claudia Jones’ reputation precedes her. She is omitted from certain parts of the Communist Party of Great Britain’s history and narratives of the radical left during the 1950-1990s in part because she challenged their failure to acknowledge the plight of colonial subjects, or to integrate an understanding of race as a modality through which class is lived into their critique of capitalism. Jones made herself both a threat and a nuisance. She was unsatisfied with a Communist Party that claimed to offer the worker emancipation while refusing to recognize black workers, and black women workers especially, as co-collaborators in that vision.

Claudia Jones: A life in exile by Marika Sherwood, introduction by Lola Olufemi, Lawrence & Wishart

‘Rediscovered’ by Buzz Johnson in the 1980s, what we know about Claudia’s life we know through a process of excavation. Archivists have pieced together the details of her expulsion from the USA under McCarthyism, her life in prison and her political organizing in the UK from her papers, political speeches and the memories of those she touched.

Though insufficient, excavation seems fitting for Claudia. It makes sense that we can only know her through other people because hers was a life lived for others, mirroring her belief in a core feminist principle: collective liberation. We only have scraps of her autobiography, but, like all those whose lives are defined by struggle, she always had one eye on tomorrow. In surviving pages of her autobiography, she writes: ‘Tonight I tried to imagine what life would be like in the future … on the broad highway of Tomorrow, despite craggy hills and unforeseen gullies, I am certain that mankind will take the high road to a socialist future.’ She was surer of this than anything else: ‘My certitude for this broad future has never matched my certitude for my personal fortunes.’

A life of service

Jones’ life was one of service; one lived in the pursuit of dignified existence, in search of the promise of the communist horizon. On this side of the temporal ledge looking back, we ask: Do you remember Claudia Jones? Perhaps it is better to ask: How do we remember Jones and the women who emerged from her legacy in ways that articulate their persistence against hegemony, against militarism, against the misery of the economic base and ideological superstructure that continue to shape the way we live?

In her treatise ‘An end to the neglect of the problems of the Negro woman!’ published in 1949, she wrote in the spirit of the Marxist tradition, ‘The bourgeoisie is fearful of the militancy of the black woman, and for good reason.’ Jones understood her own power and the menacing potential of political consciousness. Throughout her life, her position as a communist was no doubt contentious, no doubt alienating, but always the basis of her political endeavours. Indeed, Claudia’s leadership, organizing work and recruitment strategies were so threatening to the state that she was put under surveillance, imprisoned four times and finally deported from the USA to Britain in 1955 for her affiliations to the Communist Party USA (CPUSA).

A revolutionary life often involves risks to personal freedom and safety. Jones’ imprisonment and the long-lasting connections she forged with other political prisoners illustrate the consequences of principled resistance. In many ways, her strategy was simple: to give the worker the tools needed to understand their position under extractive capitalism. Becoming a member of the Communist Youth League in 1936, Jones’ years in the CPUSA were spent honing an analysis of the position of the black woman worker, and building a framework to understand her standing in the party as well as the conditions and confinement of her wage under capitalism. She found a way to articulate the historical circumstances that led to black people’s illegibility under the category ‘worker’ and thus their widespread exclusion from trade union affairs.

Jones expanded Marxist-Leninist notions of super-exploitation to the condition of black workers, including women, in the colonies and the imperial core. She developed an anti-imperialist analysis of racialism that clarified its origins in the colonial project. Jones’ staunch anti-imperialism contoured her liberatory work; she began several initiatives to organize formerly colonized peoples in the UK, affirming a political consciousness that eschewed borders. She was determined to understand how workers across the world could unite.

Despite the grand nature of her political vision, the problem of citizenship marked her life. Jones’ location was determined by which nations she could enter and what permissions they gave her to travel. One might argue that she was an internationalist out of necessity; being so forcefully expelled from the US and curtailed in her travels due to the denial of a passport by the British state, what allegiance could someone like her have had to the nation or the fictions that uphold it?

Alongside her commitment to internationalism came an insistence that the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB) provide a vision of liberation that articulated how the workers’ struggle was inseparable from the struggle against imperialism. When she represented Vauxhall and Tulse Hill at the 25th Congress of the CPGB in 1957, she pressed, ‘Colonial, and particularly coloured peoples in Britain will also want to know what policy the Party Congress advances to meet the special problems facing them in the present economic situation – the same monopoly capitalists in Britain who exploit the British working class, but who super-exploit the colonies.’ When her ‘comrades’ branded those in the colonies ‘backward’ she struck back, arguing:

The ‘backwards’ people of China and the backward people of Czarist Russia were the first to throw off the old regimes, and are now going forward with the most advanced ideology … whilst the technically advanced peoples in the Western bourgeois democratic tradition are still steeped in the mire of backward imperialist ideology. The anti-imperialist struggles of the backward Afro-Asian nations, from Egypt to Ghana, are today leading the anti-imperialist ideological struggle.

Thus, whilst Claudia was admonished by some sects of the Communist Party in the UK, her name was known across the world. The struggle took her to the USSR, to China; she had comrades in Ghana, South Africa and across the African continent. Upon her death, Tang Ming Chao of the China Peace Committee wrote, ‘Comrade Jones was a proletarian internationalist. Her whole life was that of a revolutionary and militant fighter.’ The Soviet Women’s Committee remembered her as ‘a tireless fighter for the triumph of the brightest ideals, and peace and friendship among nations.’ She left echoes and traces everywhere.

A disserviced life

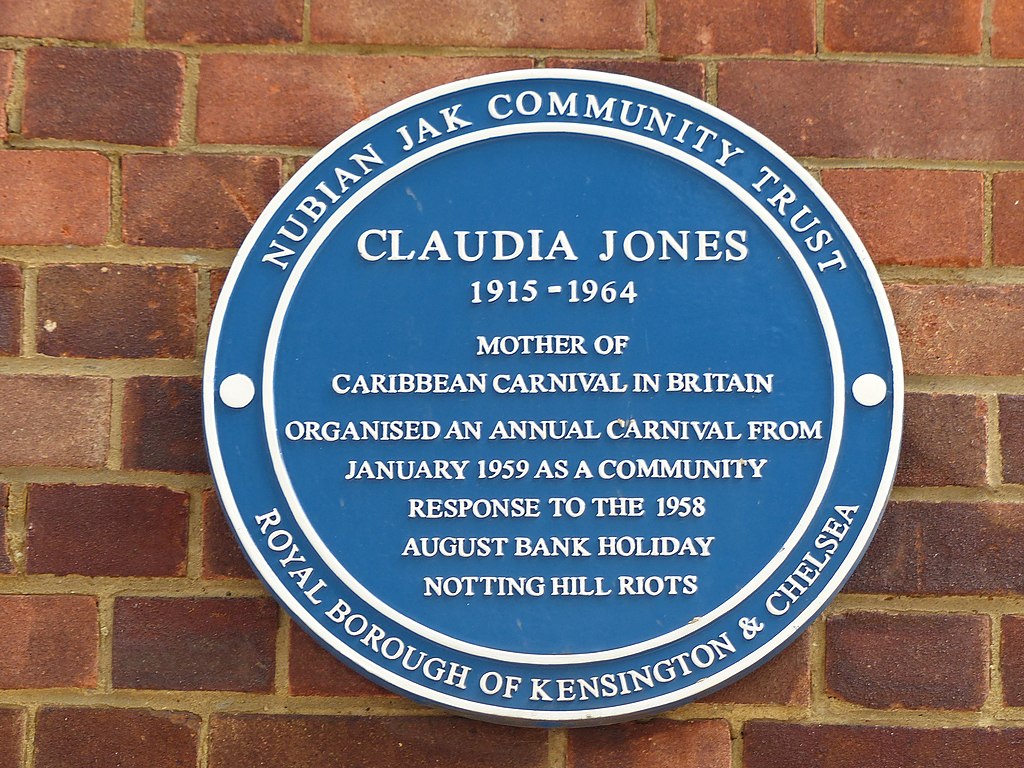

There is a tendency to downplay Jones’ political tenacity in biographies of her life – to remember her solely as ‘the mother of carnival’ is to do her a disservice. Her presence and memory loom large; what is clear is that she touched people across a myriad of political spheres and, in doing so, changed their conception of what was possible to demand for themselves and others. Friends remember her as an orator capable of isolating, distilling and then elucidating a problem. Corinne Skinner-Carter remembers how, ‘She pulled out the things in people that they thought could never be done’, always framing analysis in terms that could be widely understood. She skilfully reminded comrades that editorials in the West Indian Gazette were not ‘a treatise or a legal argument’ but were intended to be understood by everyone.

Claudia recognized the areas where her work and organizing abilities would be most constructive and moved strategically, using her knowledge and skill as a journalist as a means of radicalization. The West Indian Gazette’s seven-year run is perhaps one of the greatest attempts at diasporic mobilization and political education in recent history. It is important to note that with others, Jones managed its finances and editorial output, in the face of threats from the Klu Klux Klan, fascists marshalled by Oswald Mosley, and amid a backdrop of constant threats against her life. When the CPGB became a dead end in 1958, Jones set her sights on organizing against the colour bar. She mobilized hundreds, including artists and community leaders, to take up the fight against the Immigration Act of 1962, in the wake of race riots in Notting Hill in 1958 and the murder of Kelso Cochrane in 1959. Her wide array of friends and acquaintances – Paul and Essie Robeson, Pearl Prescod, A. Manchanda, Elizabeth Gurley-Flynn, Amy Ashwood Garvey, George Lamming, Ben Davis – and brief encounters with the likes of Martin Luther King, Pablo Picasso and Mao Zedong tells us something about the plurality of her political mission.

Claudia Jones understood that the work of liberation is the work of many hands and that a political life without space for joy, creation, music and artistry was incomplete. Her work with others establishing the UK’s first Caribbean carnival must be understood as an extension of her political love for people, for the Caribbean community and a dynamic black culture that continues to evolve. Claudia’s Caribbean Carnival Committee began in response to the riots of the late 1950s and part of its proceeds went towards the fines imposed on black youth harassed by the police. Contemporary political movements have much to learn from her imaginative response to state violence and her ability to temporarily transform the treacherous conditions of post-war Britain into a space capable of sustaining black life.

Jones is rarely remembered as an artist in her own right. Her political practice survives in her poetry, which, more so than any speech or diary entry, best captures her belief in the fraternity of peoples and their ability to love, protect and provide for one another. In an unpublished poem For Consuela, Anti-fascista, sent to Puerto Rican nationalist Blanca Canales, she wrote:

It seems I knew you long before our common ties—of conscious choice

Threw under single skies, those like us

Who, fused by our mold

Became their targets, as of old.

In 1964, on a plane to Peking, she wrote:

Change the mind of Man

Against the corruption of centuries

Of feudal-bourgeois, capitalist ideas

The fusion of courage and clarity of

Polemic against misleaders

Who sought compromise with the enemy

These were the pre-requisites of

Victory.

Claudia’s poetic voice is infused with a radical determination to name the structures that exploit, oppress and restrict us, and then destroy them. She understood like Toni Cade Bambara that the role of the artist is to make the revolution irresistible by any and all means necessary. Poetry was another arena in which to hone and express her liberatory desire, to tap into the affective realm of political imagination – what freedom would feel like. Among her friends were artists, performers and writers, many wary of her political discipline but drawn to her skill for translation, for shape-shifting and for illustrating connections between race, gender and class, between art and emancipation, between the individual worker and the means of production that were there for the taking.

Claudia Jones: A Life in Exile offers a refreshing approach to Claudia’s life. It is a book of memories of her time in the UK that is littered with holes. There are gaps, omissions, archival material that is contentious, hints at what is yet to be recovered. All of it highlights Claudia’s strange magic, the ability to live many lives in a single body. It goes beyond an account of her life in terms of location and action and instead attempts to recreate the general mood of her political work and her relationships with others. In a non-linear and fragmentary way, it elucidates the conditions that make a revolutionary and the mess we make of remembering them.

Many will know that Claudia is buried to the left of Karl Marx but not that she suffered debilitating illness, including persistent heart problems linked to tuberculosis throughout her most active political years. This fact is important; her life and work exist in the context of a world determined to kill her, in part by blocking access to financial and medical resources that might have extended her life. Many know her as a journalist, founder of The West Indian Gazette and key member of the Caribbean Carnival Committee but not as a poet and a communist. Though we can run our fingers along the threads she sewed that extend into the moment I am writing this, many do not know that Claudia died in relative poverty, alone. Even those in closest proximity to her, who loved her unendingly, claim that she kept them at arm’s length.

Perhaps the task is not to try and know Claudia Jones in her entirety, as if such a thing were possible. Perhaps the task is to understand how the political promise she dedicated her life to lives on through others and can live on in us too if we take seriously the promise of the communist horizon. This book prompts reflection on how unglamorous a life lived in struggle can be. It suggests that to remember Claudia is to commit ourselves to defending life against all those systems that kill us prematurely, just as she did.

This text is an edited version of the introduction by Lola Olufemi to Marika Sherwood’s biography Claudia Jones: A life in exile, Lawrence & Wishart, 2021.