Before I begin there is something I must explain. I will not address the problem of how one should deal with solidarity against; instead, I will focus on solidarity for. Moreover, I will not talk very much about solidarity as loyalty, even though loyalty is the most important ingredient in solidarity. Solidarity/loyalty can also be found among thieves, criminals, religious groups and various minorities, which means that an idyllic view of the phenomenon is problematic. And two further explanations: first, I will analyse the content of the word ‘solidarity’ not for the sake of linguistics, but in the belief that words contain memories as well as many other experiences, often conflicting ones. Second, I will talk a little about Solidarity, the trade union in Poland, which was created in August 1980 and crushed in December 1981.

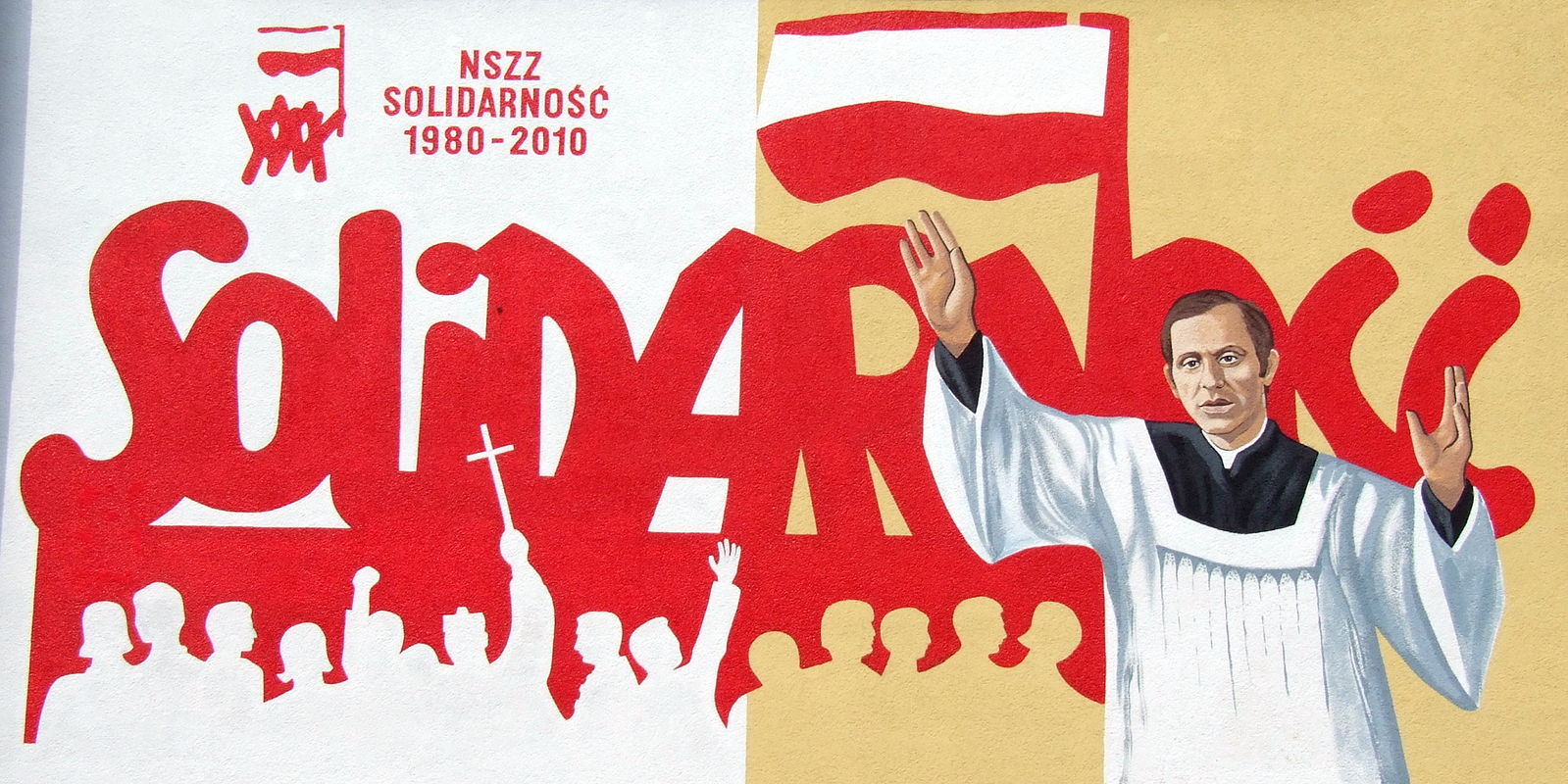

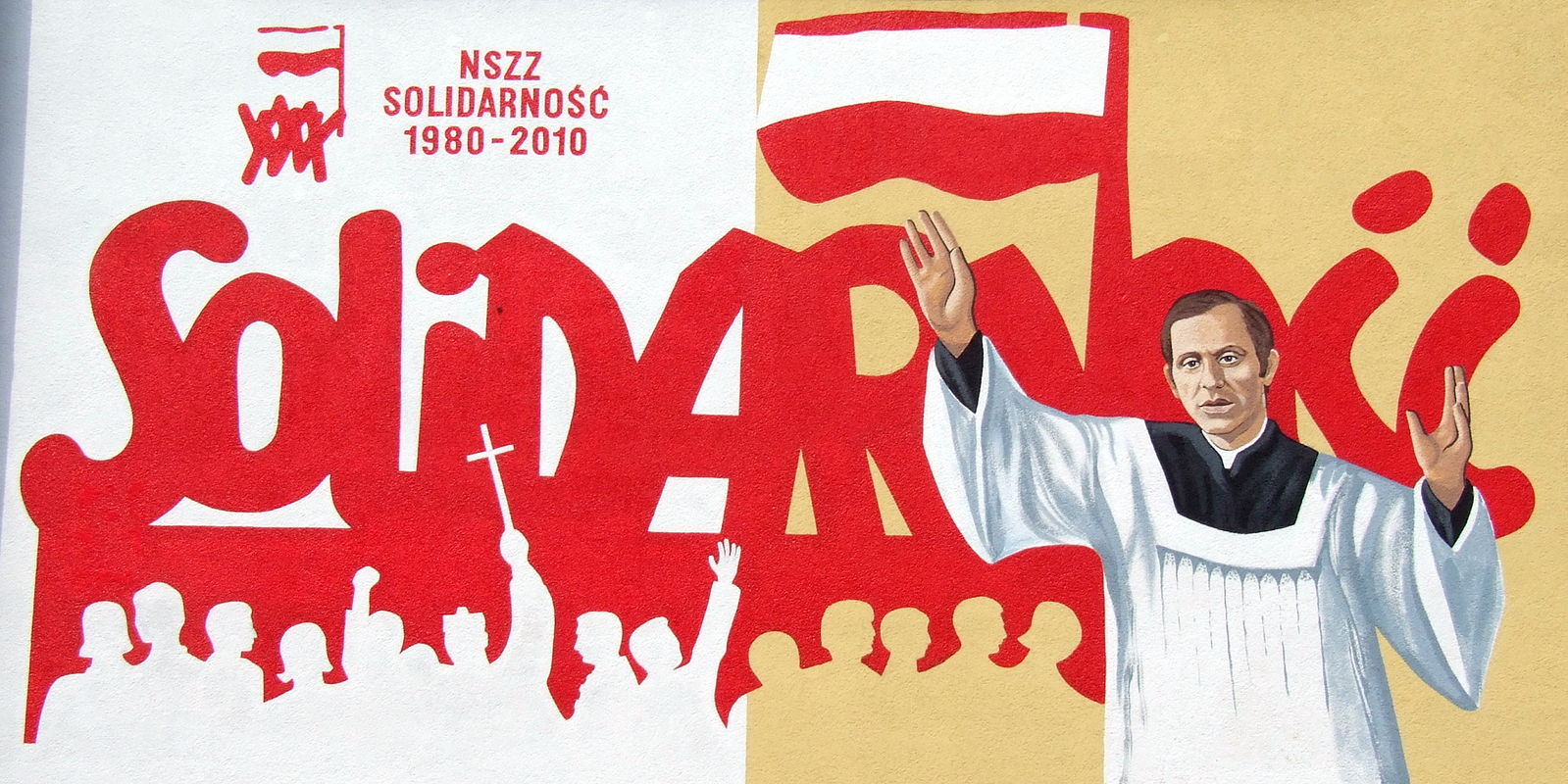

30-years of Solidarity mural in Ostrowiec Swietokrzyski (priest Jerzy Popiełuszko in foreground), 2010. Photo source: Wikipedia

1.

The word solidarity is a French invention, more specifically of the Enlightenment. In the Encyclopédie (1765), ‘solidarité’ was defined as mutual responsibility, but it was also used in the sense of ‘independent, complete, whole’ (from solidaire). It was from French that the word made its way into English and other languages. In a number of other European languages, however, the word emerged and was assimilated only in the second half of the nineteenth century. Originally, it derives from Latin and was related to money: solidum in Rome meant the whole sum, the capital.

We thus have two almost contrary meanings. The original one is based on the idea of a firm point that guarantees and creates independence. Its foundation can be economic, that one owns the whole sum, the capital, the lot, and in this way becomes independent. But it can also mean that one takes joint responsibility for somebody or something, that one creates a community of mutuality, where as a member of the group one acts with consideration and without self-interest, for the benefit of this group or its individuals. Here, the personal and the common intersect. Economic independence is based upon capital, that is to say, something over which the individual has power (and which can be formulated as: ‘I have the whole sum, which is my firm point and guarantee’). At the same time, this refers to a guarantee that lies outside of human control, namely the economy. Everything that enables such independence must be part of the financial exchange represented by money. Mutual responsibility, in contrast, depends on trust, based upon the inner reliability of the group. This was how Józef Tischner reasoned concerning the ‘ethics of solidarity’ (the title of his book), which arise in the encounter with the ‘Other’, who can be very different indeed. Reasoning thus, all foundations are erased. Responsibility for and openness towards that which is different becomes a groundless ground, an imperative. Tischner followed in the footsteps of Emmanuel Levinas, but tried to interpret him through Christianity.

However, things are not always as simple and idyllic as that. The word ‘solidarity’ has explosive potential. Its content tends to find robust, less fickle grounds: ideology, nationalism, xenophobia, misogyny, homophobia, politics, religion, etc. This is where ‘solidarity against’ tends to form, when one needs to find and to defend a strong identity.

Economic independence is secure as long as there is an economy. But the ‘whole sum’, as we know, can evaporate during revolutions, catastrophes or crises. Ethical independence, too, can be unstable, momentary, ecstatic and explosive: as in a solidarity based upon the closing of ranks against, the exclusion of or rejection of the other. To retain these senses in a single word would seem an impossible task. And yet, in spite of everything, some kind of impracticable, impossible attachment happens. ‘Solidarity’ is a child of the moment. The English word ‘solid’ has preserved this opposition: it means massive and compact, but also steady, firm, strong, stable, reliable. Not only that: ‘solid’ can also mean affluent and creditworthy.

2.

When strikes broke out across Poland the autumn of 1980, it was difficult to find a name for the new phenomenon.

The story is simple enough. In August 1980, a strike broke out at the shipyard in Gdansk. The workers, who were among the fairly well paid, wanted a raise. In the People’s Republic of Poland, such a matter was not difficult to resolve. Either one agreed to the demands of the workers, or one called in the police, the military; this had been done before and claimed victims. The workers demanded a meeting with high-ranking politicians in order to solve the conflict, and the politicians agreed to it. But they were in for a surprise. The negotiations took place in public: apart from the strike committee, other workers also participated (through the internal radio at the shipyard). And the workers moved between the room where the negotiations took place and other places in the shipyard. Every decision made by the strikers’ committee was a joint decision.

Among other things, it transpired that a female worker had been sacked for political reasons. The strike committee demanded that she be reinstated. The politicians agreed. But it turned out that many of those who had cooperated with the workers at the shipyard in Gdansk had been imprisoned, and the strike committee demanded that the politicians free them, along with all other political prisoners.

The authorities would not agree to this. Now the issue was no longer Gdansk, the shipyard or money. It was no longer a strike, but a kind of revolution: all strike rules were broken, it was no longer a struggle based on self-interest, and before the politicians had time to find a solution (either agree to the demands or suppress the revolt by force), strikes had broken out across the country, primarily in big enterprises: mines, ironworks and other sectors of great importance for the economy. In these cases as well, the strikers were among the fairly well paid. Money and economic exchange ceased to be the foundation or model for representation. Some strikes demanded compensation for low-wage groups, instead of simply a rise in wages.

I am not going to relate the whole history of the Solidarity movement. What I want to point out here is that this is where the attachment, the inner connection contained in the word solidarity is most clearly manifested. One begins by acting out of self-interest, and suddenly this horizon is transcended.

What was this new phenomenon to be called? It was clear that what had been created deserved to be called a union. At the same time, it was clearly not a union. Those involved were conscious that the strikes had succeeded by virtue of solidarity, but the word itself had become somewhat overused in official propaganda, where one had to declare one’s solidarity with everything that the authorities pointed to. Thus, the name: ‘The Trade Union Solidarity’ sounded somewhat suspicious. The word ‘Independent’ was therefore added: ‘the Independent Trade Union Solidarity’. But not even this was satisfactory. Why? I think it was because the word ‘independent’ pointed to the outside world or, in plain language, to the authorities. It emphasized that those within the movement were independent from ‘the people’ who could no longer influence them.

Intuitively, those involved wanted to find a name that both preserved and erased the connection between unselfishness and solidity. So yet another word was added: ‘self-governing’. Rather amusingly, then, the name of the emerging movement finally became, in its entirety, ‘the Independent Self-governing Trade Union Solidarity’ – a kind of explication of what was originally, from the very beginning, contained in the simple word solidarity. And so a relatively small strike by the workers at the shipyard in Gdansk turned into a very solid movement: out of Poland’s population of 33 million, 10 million became members.

3.

Suddenly a new player had burst onto the political stage. ‘Independent, self-governing’ – could such a thing be accomplished? Simultaneously it expressed an attachment with explosive energy. At once, Solidarity became a troublesome player for the others, that is to say the Communists and the Catholic Church. Interestingly, when ‘Solidarity’ took off, it remained a democratic movement. It was extremely decentralized, in accordance with the pattern set during the strikes. Weaker organizations or companies could count on the support of the stronger ones. Strikes broke out almost incessantly. The other players, the Party and the Church, were hierarchic or feudal. Decisions in such structures can only be made by one or a few persons. In Solidarity this was, paradoxically, both impossible and necessary: one had to adapt to the other participants. The country was on the brink of economic and social disaster.

A paradox. When the movement emerged, it was as a form of solidarity with vulnerable groups – workers, farmers, political prisoners and the intelligentsia. How is this compatible with its enormous force, which led to the movement becoming a massive majority in the country? Solidarity was so proud of this success that it might be interpreted as complacency.

4.

Among the many literary and scientific works of Pyotr Alexeyevich Kropotkin (1842–1921), there is one entitled Mutual Aid (1902). In it, he repudiates Darwinism’s ‘struggle for existence’ and claims that it is not competition but solidarity that is the main driving force of evolution. Kropotkin was a Russian aristocrat. In the second half of the 1860s, he spent a few years in Siberia, where he worked as a civil servant and geographer and experienced revolts among exiled socialists and Polacks, which were bloodily suppressed. Geographically, his writing had its origins in what are perhaps the most inhospitable areas conceivable, where the conditions are extremely difficult for people and animals. Politically, it dealt with Russia, that is to say, a country with an extremely autocratic and unrestrained government. Socially, the background of his work was formed by the theories of Darwin and his followers, in particular ‘social Darwinism’, which claimed that the struggle for existence is the core of evolution in both animals and people, and that the stronger, better adapted will be victorious. Everything is about competing with and forcing out your competitors (the rat race).

But this did not accord with Kropotkin’s experiences in Siberia. He pointed out that even the animals in these harsh conditions transcended the principle of Darwin, and that people stood by and supported one another. This eventually became the core of anarchism. ‘Mutual aid’, regardless of one’s political stance, says a lot about our paradoxical situation: even under difficult conditions, we can show solidarity, and this might be the principle of evolution. Now, perhaps this only happens in a state of emergency, as an exception; but perhaps this exceptional state of emergency is to be found not outside us, but inside? In which case, it happens instantaneously, and in a sudden rift or an unexpected attachment. On this point, Kropotkin would certainly not agree with me – but I am convinced that the rift or attachment is something that can be expressed only in art, in an instant of explosion. That is to say – and here I am again close to Kropotkin – in an extreme decentralization and individualization of life.

5.

Prince Pyotr Kropotkin died 1921 in Dmitrov. He was given a state funeral, despite the fact that he had been forceful in his opposition to the Bolsheviks and the Communists. ‘Where there is power, there is no freedom’, he claimed. A mass procession followed his body on its last journey, both in Dmitrov and in Moscow where he was buried. A hundred thousand people turned out, despite the terror that prevailed in Russia. They carried the banners of anarchy and signs demanding that their fellow anarchists be released from prison. It has been claimed that this was the largest voluntary demonstration in the history of the Soviet Union, and the last on such a scale. Politics aside, the demonstration very much confirmed Kropotkin’s theory. People conquered their fear – instantaneously. This was what happened in Siberia in 1884, in Moscow in 1921, and in Poland in 1980. But this was also what happened in Sweden in 1968, and in Czechoslovakia in 1968. The same is true of the recent revolutions in Iran, Tunisia, and Egypt: explosions of solidarity.

6.

Jacques Derrida once wrote about hospitality. Among other things, he pointed out how strongly hospitality is connected to the regulating norms of the law, and how much it depends on unselfishness, against a background of relations of power. We are visited by someone extremely different. We don’t know for sure if the other has come to visit us or to haunt us. Derrida inscribes this event in the Messianic tradition. He writes about the risks that the host takes in opening his or her door to a stranger: a stranger who might be Jesus, the Messiah or a murderer. In its explosive phase, solidarity opens a door, takes the risk. But solidarity also contains other foundations, leading to a closed door.