Olivier Corpet, the journals editor and director of the Institute for Contemporary Publishing Archives, passed away on 6 October. In the 1980s he was a central figure in the founding of the European Meeting of Cultural Journals, the informal network that developed into Eurozine. Carl Henrik Fredriksson and Klaus Nellen, Eurozine co-founders, pay tribute to Corpet.

In France, Olivier Corpet was known as the longtime director of IMEC, Institut Mémoires de l’édition contemporaine. IMEC is one of France’s most important literary institutions, hosting the estates of writers and philosophers such as Louis Althusser, Samuel Beckett, Marguerite Duras, Frantz Fanon, Michel Foucault and Alain Robbe-Grillet. The latter was a close friend of Corpet’s and the subject of several of his publications. It was Olivier Corpet who developed IMEC into the institution it is today, and it was above all for this achievement that he received the order Officier des Arts et des Lettres from Jack Lang in 2013.

First and foremost, however, Olivier Corpet was a ‘journals man’, a self-declared revuiste. As such, he was a key person in the international circle of editors of cultural journals that formed in the early 1980s and which, not entirely to his liking, developed into the Eurozine network. When, 15 years later, Eurozine set out to make use of the developing digital technology – the internet – to breathe new life into the editors’ network, it was for Corpet a risky and perhaps even foolhardy endeavour.

It was the German radio journalist Hans Götz Oxenius who, almost four decades ago, had the idea to encourage European editors to start talking to each other. Looking back, Oxenius noted that it all started with ‘the observation that it was the journal editors that were the swiftest to inform about the intellectual, literary and political situation of a country’, but that these editors did not know much about each other. So, he asked ‘some experts’ to help alleviate the communication problem, among them the German writer Hans Magnus Enzensberger, publisher of the influential journal Kursbuch and, of course, Olivier Corpet, who had written his dissertation on the political-philosophical publication Arguments and was about to found both the association Ent’revues and La Revue des revues, a journal of and on journals.

The result was the first ‘European meeting of cultural journals’ in Bossey, Switzerland in 1983. Olivier Corpet not only participated in the annual meetings that followed, he also became their spiritus rector, gathering around him an inner circle, which he ironically referred to as the ‘Central Committee’.

In a report on the Lisbon meeting in 1994, Corpet looked back on the first decade of the journals gatherings: ‘These meetings have kept their original style of conviviality, generosity and climate of open discussion,’ he noted. They ‘work like an ideal journal’, contributing ‘to the creation of a broad European network for reflection and exchange on (and for) journals’, thus helping them to perceive their ‘central role in the resistance against the standardization and uncontrolled modernization of cultural practices and representations’.1 This view of journals – cultural journals – was what determined Oliver Corpet’s role within the editors’ community in the second half of the 1990s and guided his critique of the attempts to renew the network.

In a 1988 interview on ‘the life of journals’, Corpet formulated his vision of what a cultural journal is and should be:

the journal is a genre in itself, autonomous, with its own dynamic, its own logic, and as such is also a fragile product, economically weak; it requires special treatment at all levels, a treatment fitting to its specificities, and is therefore different from how we see books or the press in general. The journal is the least trivialized, and therefore the most difficult to standardize, of all publishing products … The work of journals is at the opposite end of the scale, compared to the increasingly spectacular aspects of much of the contemporary intellectual and literary scene. It can be an effective antidote to the poisons of this spectacle, precisely because it requires slow, in-depth, underground work, characterized by humility, patience and stubbornness. Efforts without any immediate effects, a bet on time. In this sense, the journal can function as an anachronistic form of creation and communication.2

When the debate took off over the consequences the World Wide Web would have for cultural journals, and when the prototypes of what was to become Eurozine were presented and discussed, Olivier Corpet was the most vocal critic. In his eyes, the internet was ‘nothing but a resort for pornography and short snippets of information, and has nothing to do with the proud tradition of printed intellectual journals’. Instead, he argued that one had to insist on the ‘anachronistic form of creation and communication’, as he had put it a decade earlier. He included this very topic on the agenda of the journals meeting in 1998, organized by him at the premises of IMEC at Abbaye d’Ardenne near Caen, Normandy.

We were all overwhelmed by the magic of the place and the generosity of our host. This was one of the finest meetings of this circle of friends, incorporating all the hopes invested in the vision of free intellectuals exchanging ideas and experiences in a culturally and historically conducive setting. The second day was devoted to the question ‘From meetings to networks: Do we need an internationale of journals?’ Once again, the question ‘Is the internet a new challenge or a serious threat for journals?’ was passionately discussed. Olivier Corpet’s answer was absolutely unequivocal.

Olivier Corpet (centre) with the British publisher John Calder (left) and the German writer Lothar Baier (right) at the European meeting of cultural journals at the Abbaye d’Ardenne, Caen, in 1998.

The editors meeting in Caen was the last that Olivier Corpet participated in. That year, Eurozine was established as both a network and a journal of its own – using the internet as its virtual base. However, it cannot be emphasized enough how much Eurozine and its partner journals owe to Olivier Corpet as an uncompromising critical voice and advocatus diaboli. Time and again he forced us to examine our editorial conscience and successfully instilled a sound scepticism towards the newest fashions.

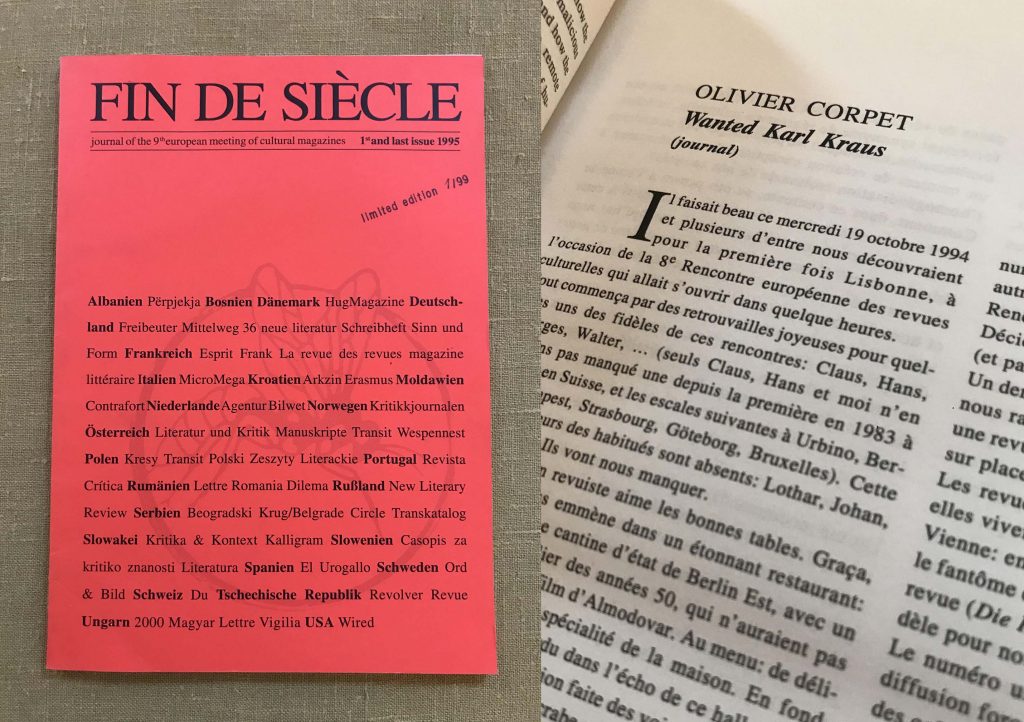

In the now legendary ‘Red Issue’, printed in 99 copies on the occasion of the 1995 meeting in Vienna, Olivier Corpet published, alongside network habitués such as Lothar Baier and Gaby Zipfel, and temporary affiliates like Tony Judt and Timothy Garton Ash, a sublime essay entitled ‘Wanted Karl Kraus (Journal)’. The topic of both the issue and the meeting was ‘Fin de Siècle: Cultural Journals at the End of the Century’. In his essay, Olivier Corpet’s concept of what a journal is and does stands out in all its ethical vigour. He cites Karl Kraus (and Confucius) as his witness:

If the ideas are not right, the words are wrong; if the words are wrong, works do not get created; if works do not get created, morality and art do not thrive; if morality and art do not thrive; justice goes awry; if justice goes awry, the nation does not know which way to turn. So one must not allow anything to be wrong with the words. That is the key to everything.

Picking up Kraus’s master key and adding Gustave Flaubert’s claim to truth, Olivier Corpet concludes: ‘To not tolerate “anything to be wrong with the words” and to “frighten all men of letters with truth itself”, would that not be a beautiful program for the journals of this fin de siècle?’

It was then and still is. Olivier Corpet’s rigorous idea of the essence and the vocation of a journal is as much a program in the early twenty-first century as it was at the end of the millennium. Perhaps even more so.

So let’s get some order into those words. Into the world.

The ‘Red Issue’, limited edition published for the 1995 ‘Fin de siècle’ meeting in Vienna, including Corpet’s article ‘Wanted Karl Kraus (Journal)’.

Olivier Corpet,’Rencontre européenne des revues culturelles [VIII] Lisbonne (Portugal), 20–23 octobre 1994’, in La Revue des revues, no. 19, 1994, 84–85, original in French, www.entrevues.org/rdr/n18/

“Que vivent les revues”. Entretien avec Olivier Corpet (1988), https://bbf.enssib.fr/consulter/bbf-1988-04-0282-003

Published 13 October 2020

Original in English

First published by Eurozine

© Carl Henrik Fredriksson / Klaus Nellen / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTIn focal points

Newsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Related Articles

The Hungarian comic tradition

2000 7/2020

In Hungarian literary journal 2000: the central-eastern European comic tradition and the humourlessness of nation-builders; why intellectual housewives don’t post food-selfies; the aesthetics of video calls and the social psychology of isolation.

For a strong start into the second season, we talk about corruption in the EU. In the basement of the European Parliament we talk Italian mafia, Orbán’s son-in-law, and the misuse of public funding in member states with MEPs.