The word essayist entered the English language as an insult. In January 1610, when William Shakespeare was working on The Tempest, the comedy Epicone, by his rival Ben Jonson, was being staged at the court of King James I. Late in the play, a clownish knight named Jack Daw recites some of his writings, which are ridiculous. Daw’s friends tease him, comparing his prose to that of Seneca and Plutarch. When Daw takes offence, his friends redouble their efforts, insisting that the two ancients ‘are very grave authors’. Daw objects. ‘Grave asses,’ he calls them, in a cheap play on words. ‘Mere essayists, a few loose sentences and that’s all’.

Daw is thought to be a satire of Francis Bacon, the great statesman and theorist of science, whose 1597 book Essayes introduced the concept of the essay into English prose. Bacon borrowed the term from Michel de Montaigne, whose first book of Essais was published in France in 1580. Like Seneca, Montaigne wrote in a personal vein, but what set him apart was that he investigated himself in a manner at once curious, rigorous, sceptical, and intimate. In France, an essayeur was an official who tested coins or grain for purity and value; similarly, an essai was an exam for a university degree. Montaigne tested the meaning and value of the movements of his mind, portraying his life as an ongoing act of thinking and writing whose findings could be challenged, overturned, or refined over time. A mind alive to its own complexities is a mind alive to those of the world.

The noun essay also entered English under a cloud. In the second scene of Shakespeare’s King Lear, first performed in 1606, Gloucester’s bastard son Edmund burns with resentment. Edmund is not the firstborn, and so he must find a way to earn a living. His choice is betrayal. He composes a text about the tyranny of parents over their children and then passes it on to his father as a letter from his brother Edgar, Gloucester’s oldest son and rightful heir. ‘I hope, for my brother’s justification, he wrote this but as an essay or taste for my virtue,’ (Act I, Scene 2) Edmund tells his father, in one of the first uses of essay in English. The trick works. Gloucester is furious about Edgar’s seeming betrayal, eventually disinheriting him and favouring Edmund. Here essay is understood to be a work of cunning and trickery. (Shakespeare teases out the same connotation in Sonnet 110: ‘These blenches gave my heart another youth/And worse essays prov’d thee my best of love’). Not without justification, Edmund challenges a social arrangement that for ages had seemed proper and reasonable, yet the few ‘loose sentences’ of his forgery betray such extreme self-interest that he seems more like Machiavelli than Montaigne.

In a twist, Edmund’s text includes criticisms of primogeniture that Shakespeare lifted from the first English translation of Montaigne’s Essais, published in 1603. By having the deceitful Edmund pass off the criticisms as Edgar’s, Shakespeare uses Montaigne’s words against themselves. But Shakespeare isn’t undermining Montaigne, or merely being clever. Between them, the two writers contributed to a seismic shift in our sense of individual autonomy and the relativity of values. In King Lear, Shakespeare dramatizes that shift through Edmund in order to better represent and explore the temperaments of his age.

*

The word ‘essayist’ has not yet become an insult in the United States, but the essay itself, the sort that Montaigne or Virginia Woolf would have welcomed, has recently fallen into disfavour. This may sound peculiar, because it seems that we are enjoying a ‘golden age’ of the essay. First-person narratives and testimonies dominate social media as well as the websites of many newspapers and magazines; they are being published more regularly in print too – not only in opinion pages, where they are old friends, but also in book reviews, which have gradually been shedding the pretence of objectivity.

The sheer volume of such writing has less to do with the popularity of the essay, however, and more with the needs of publications trying to survive in an attention economy. The model is simple. A magazine or website pays writers low fees to churn out clickable first-person pieces brimming with self-exposure and provocation; readers get a burst of gratification and then move on to the next piece, while the publication collects valuable user data and advertising revenue. But, despite being casual, fragmentary, and impromptu, these micro-narratives generally do not behave like essays. The prose of great essayists like Montaigne, James Baldwin, and Marilynne Robinson is scrupulously investigative as well as personal and informal. And whereas Francis Bacon aspired to a measured impersonality in his essays, he was also a theorist of science, and so, like Montaigne, he understood that knowledge is always an attempt, whether it happens on the page or under the lens of a microscope. What an essay reveals is where a writer’s argument with herself, or investigation of a burning question, has temporarily come to rest. Que sais-je? Montaigne asked. ‘What do I know?’ He attempted to find out by turning the microscope on himself, or a part of his world.

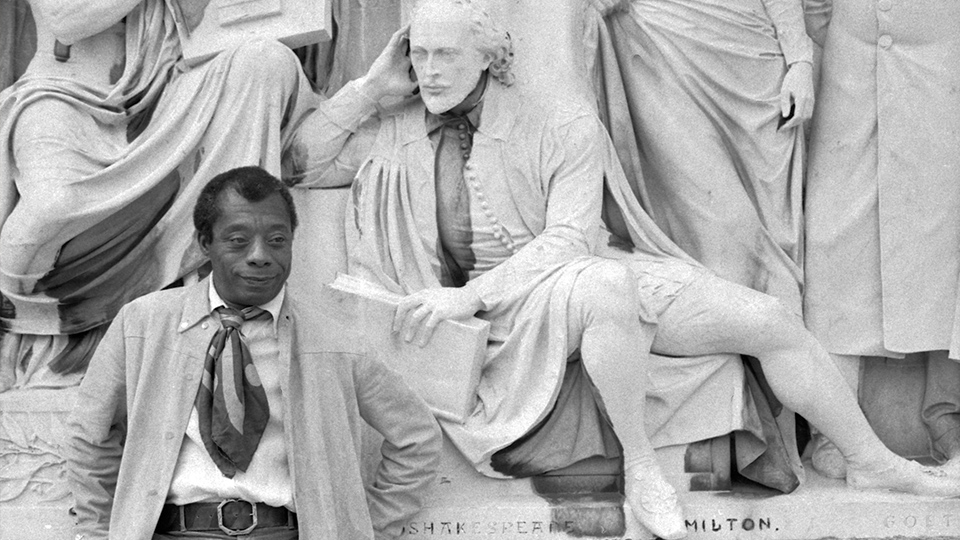

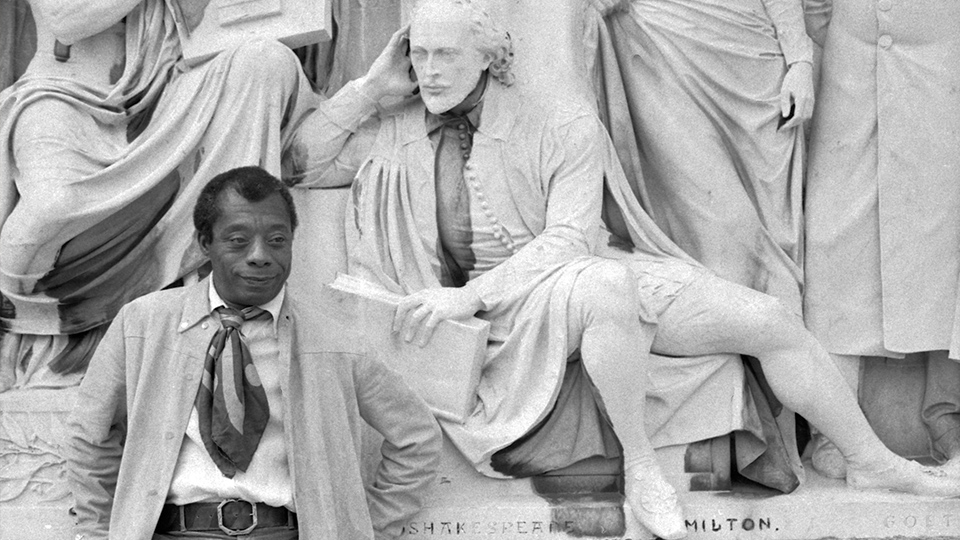

James Baldwin on the Albert Memorial with statue of Shakespeare. Photo by Allan Warren via Wikimedia Commons.

Because knowledge is always an attempt, good essayists are not content for very long with their own wisdom. Yet a dose of healthy scepticism, especially regarding political issues, is now considered by some to be a liability and a reason to be suspicious of the essay. As Jon Baskin and Anastasia Berg, two of my colleagues at The Point, explain in a recent article, since the election of Donald Trump in 2016, some American writers on the Left have emphasized the importance of ‘positioning’, or the orientation of thinking and writing entirely around the achievement of a political goal. A writer should not concern herself with airing disagreements or trying out ideas in public. Instead, ‘in addition to sometimes filtering her own public speech to advance an ideological agenda,’ Baskin and Berg observe, a writer sees herself as responsible for ‘protecting’ the public from being exposed to ideas not defined by a legitimate political strategy. Positioning emphasizes not ‘What do I know?’ but rather ‘What am I supposed to know?’

Positioning has become nearly as common in national newspapers as small literary and political magazines. In addition to its staff columnists, the New York Times now has many contributing editorial writers who see their primary mission as staying ‘on message’ rather than seeking to enlighten or persuade. It may be that editors are trying to publish essayistic, exploratory writing but are finding it hard to convince their bosses. Positioning offers the romance of conviction: in volatile political times, we are free only to be single-minded. From this perspective, any undisciplined essayist or advocate – which is to say, any person who is open-minded and self-scrutinizing – is a potential Edmund, an opportunist looking to advance his interests by recklessly challenging social norms.

*

In her introduction to the 2017 edition of The Best American Essays, an anthology published annually in the United States since 1986, guest editor Leslie Jamison explained that, after Trump’s victory, she was of two minds about the romance of conviction. She admits that, on the morning after the election, ‘I thought maybe nothing mattered but policy op-eds and marching. Maybe nothing mattered but articles about politics with a capital P’. But, after some time, she changed her mind: ‘Essays are political not just when they take up the kinds of content we call political with a capital P – social justice, civic life, the rule of law and government – but because they are committed to instability. They are full of self-interrogation, suspicious of received narratives, hospitable to contradiction … The essay insists that every consciousness yields infinite complexity upon close scrutiny. This is something close to the precise ethical opposite of xenophobia or scapegoating.’ For Jamison, the essay’s tendency toward wide-ranging curiosity might disrupt normative opinions and foster a healthy scepticism of politics. The essay could help to preserve a spirit of democratic distrust.

Changing places

Read Jyoti Mistry on how the alleged colour blindness of Swedish society robs transnational adoptees of words for the very real discrimination they face.

A few loose sentences

Read John Palattella argue that even in a very divisive age, the inherent ambiguity of the essay is not passé.

Jamison’s double vision of the essay may have been hard won, but it is not entirely clear. How can the essay speak unequivocally for a particular point of view – ‘politics with a capital P’, as she puts it, and also be sceptical and anti-dogmatic, ‘committed to instability’ and ‘full of self-interrogation?’ How is it possible to insist on the necessity of positioning while simultaneously questioning all positions? Something else is confusing as well: not all of the twenty pieces that Jamison selected for the anthology (all published in 2016) are essays. Several are, rather, polemics, controversial for the sake of being entertaining and infuriating. (The root meaning of polemic is belligerent, which is antithetical to the essay.) A piece by the writer June Thunderstorm, for example, delivers what her pseudonym promises: a hard summer rain on the victory parades of anti-smoking advocates.

Another wrinkle is that all of Jamison’s selections first appeared in publications that are clearly on the left of the political spectrum in the United States, such The New York Times Magazine, n+1, Granta, Transition, The Baffler and Harper’s Magazine. The same is true of the twenty-four essays selected by Hilton Als for the 2018 edition of Best American Essays. Jamison’s and Als’s sense of politics is narrow: apparently, conservatives are not suspicious of received narratives. Als is even more adamant than Jamison about the necessity of positioning. Essays of the future, he stresses in his introduction, ‘will or should start with questions, generally political in nature, and if you don’t think so, think again’. Moreover, Als insists that such essays are destined to take a particular form: living ‘as we do in a broken world, essays are bound to become more broken, fractured, as power becomes insistent on sowing its power further by breaking more backs, jailing the innocent, cracking Love in the knees’.

Jamison’s and Als’s tailoring of the essay to a political purpose and persuasion is uncharacteristic of the BAE series. In the introduction to the 2002 edition, guest editor Stephen J. Gould explained that he ‘was tempted solely to make a collection of 9/11 pieces (so many good ones already, and so many more yet to come), but neither decency nor common morality permitted such a course. We simply cannot allow evil madmen to define history in this way’. What Gould sought to avoid was reducing the volume’s contents to the political mood or personalities of a particular moment, however overwhelming its many tragedies and horrors. Of the 2002 volume’s twenty-four essays, only eight are about 9/11, the World Trade Centre, or terrorism. Of the sixteen others, several concern higher education, one is about the restoration of a Stradivarius violoncello from 1707, and another is a defence of literature by Mario Vargas Llosa. With calm determination and a dose of conservatism, Gould was doing whatever he could to deter American society from turning inward and becoming too assertively, too hopelessly, too destructively itself.

In a way, Gould was following Montaigne’s example. In his foreword to the 2018 edition, Robert Atwan, who founded and manages the BAE series, suggested that a strain of conservatism may have imbued Montaigne’s scepticism. Montaigne was open to ideas and a way of thinking that were anything but tranquil, yet he also ‘took comfort in his title, his possessions, his estate, his routines, his Catholicism,’ Atwan writes. ‘Since no single way of life could be proven to be superior to another,’ he surmises, ‘no one government to another, then one may well relax and accept … the standards of life that one’s community offers’.

Perhaps Montaigne feared that living his entire life in accordance with his scepticism would make daily life impossible. Perhaps he found comfort in the paradox that ‘to say that knowledge consists of knowing that nothing can be known for certain is to express a certainty,’ as Atwan writes. What is clear is that, beginning with Montaigne, scepticism of dogmatism, of thought congealed into an unquestioned position or proposition, has been an enduring characteristic of the essay. Such scepticism can be a highly fluctuating thing, turning against the idea that a particular politics or way of life is continuous with essay writing, or that an essay written in a broken style is bound to have more efficacy than one written plainly.

*

The Best American Essay series, which since its debut in 1986 now stands at thirty-two volumes, is an excellent accidental history of the ways in which the essay has endured and changed in the USA during the past three decades. Guest editors of the anthologies have been essayists as well as novelists, poets, journalists, editors, historians, natural scientists, psychologists, and physicists. The guest editor of each volume is responsible for writing an introduction and selecting twenty or so essays from a pool of approximately one hundred, gathered by Atwan. In some volumes, essays from large-circulation trade magazines like The New Yorker, Vanity Fair, or The New York Times Magazine dominate the selections; in others, selections from little magazines like The Threepenny Review, Raritan, Salmagundi, or Granta hold sway. Over time, the series has offered a rich and extensive sample of essayists, prose styles, and editorial tastes, showing that essays are still being written even as the demands of journalism have pushed writers in the direction of reportage, profile writing, and positioning.

An alternative to BAE is The Oxford Book of Essays, edited by John Gross. Published in 1991, the anthology contains one hundred and forty essays by British and American writers from the early 1600s to the late twentieth century, presenting the essay as a form of wisdom literature. Stalwart supporters of the essay in the UK include the ‘Freelance’ column of the Times Literary Supplement, Janan Ganesh at the Financial Times, and the pages of the London Review of Books, especially its ‘Diary’.

In the BAE series, a recurring theme in many of the guest editors’ introductions is the difference between the article and the essay. Atwan introduced the theme in his foreword to the 1986 edition. The article, by which he means a newspaper or magazine piece as well as an academic paper, is utilitarian – ‘informative, impersonal, subject-bound’. It has a timely subject and distinct purpose, and therefore a short shelf-life. The essay, on the other hand, is dynamic, ‘now settling down with ideas and exposition, now searching for eloquence and charm’, and doesn’t come with an expiry date.

Guest editor Elizabeth Hardwick turned this opposition into high drama in her introduction to the 1986 volume. Taking her cue from William Gass, she calls the article ‘an awful object’ that is ‘under the command of defensiveness in footnote, reference, coverage’. It has the polish of ‘the scrubbed step – practical economy and neatness’. The essay, however, ‘is a great meadow of style and personal manner, freed from the need for defence except that provided by an individual intelligence and sparkle … Knowledge hereby attained, great indeed, is again wanted for the pleasure of itself’.

Cynthia Ozick, like Hardwick and Gass a novelist and an essayist, struck a similar note in her introduction to the 1998 volume. ‘The essay’s utility lies in its uselessness: it has no educational, polemical, or sociopolitical use’, she claims. ‘An article is gossip. An essay is reflection and insight’. Ozick was repeating a complaint she had made five years earlier in an essay entitled ‘It takes a great deal of history to produce a little literature’, where she bemoaned ‘the eclipse of the essay in favour of the “article” – that shabby, team-driven, ugly, truncated, underdeveloped, speedy, breezy, cheap, impatient thing’. She continues: ‘The essay is gradual and patient. The article is quick, restless, and brief. The essay reflects on its predecessors, and spirals organically out of a context, like a green twig from a living branch. The article rushes on, amnesiac, despising the meditative, revelling in the gossip and polemic, a courtier of the moment’.

Gass and Hardwick belittle the article to elevate the essay. The essay and the article are both prose, but the article is all work and no play, a factory instead of a meadow or a salon. Ozick’s approach is different. She aims to demolish the article to justify her definition of the essay. Yet her case for the essay rests on excessive special pleading, which has the effect of making the essay seem fragile despite the intellectual vigour she finds in it.

In certain respects, Ozick does not see eye to eye with Leslie Jamison either. Whereas Ozick cherishes the essay’s uselessness, Jamison emphasizes its capacity for social engagement. The two writers are, however, united in treating the genuine essayist as a heroic figure. Their approach sets them apart from Atwan, who while acknowledging that the article and essay are different, nevertheless treats them as prosaic siblings, since each establishes knowledge through different narrative and analytic methods. The article, by necessity, separates reason from the imagination, whereas the essay puts them in conversation.

*

There is a grain of truth in the deceitful letter written by Edmund in King Lear – sometimes an essay does live in disguise. Consider the work of Larissa MacFarquhar, a staff writer for The New Yorker and one of the most talented and imaginative non-fiction writers in the United States today. She is best known for articles about poets and novelists such as John Ashbery and Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, philosophers like Paul and Patricia Churchland and Derek Parfit, and cultural figures as varied as Quentin Tarantino and Aaron Swartz (an American computer programmer and ‘hacktivist’ who took his own life in 2013).

MacFarquhar’s magazine pieces are commonly known as profiles because they tell the life-story of someone who is in the news or has reached a professional milestone. But that label does not do justice to her work. In the United States, two common conventions of the magazine profile are the use of first-person narrative and offhand, anthropological descriptions of a subject’s physical appearance and favourite foods (the more glamorous or eccentric the better). MacFarquhar ignores these conventions because they establish a wall between a subject and the reader. As she explained several years ago to The Guardian, what she is trying to do by blending the force of fact with the narrative capaciousness of prose is ‘to get at a sense of intimacy, a sense that you are, insofar as possible, inside the mind of the person, so that you understand why they’re in love with the ideas they fell in love with, what moves them, what drives them.’ MacFarquhar breaks the wall in order to represent with great depth and sensitivity the movements of another person’s mind. At times MacFarquhar’s narration and analysis is so suffused with a subject’s thoughts and inflections of speech that it sounds as though her subject could have narrated the profile. Her profile of Adiche works similarly but in a different way because it reads like a short story.

MacFarquhar’s work has never been included in Best American Essays, perhaps because it behaves too much like fiction. Her preference for using free indirect discourse – allowing a subject’s voice or mannerisms to suffuse the narration – is common in the novel but less so in non-fiction. Another writer noticeably absent from the BAE series is Ta-Nehisi Coates, best known for the essay ‘The case for reparations’, which appeared in The Atlantic in 2008, and his books Between the World and Me (2015) and The Beautiful Struggle (2008). Combining history and reportage, ‘The case for reparations’ argues that the systematic depredations visited upon black citizens by the US government since the nation’s founding are reason enough to reconsider the need for a congressional bill to reexamine slavery’s lingering effects and contemplate remedies for them.

But Coates’s essay is no arid policy paper. Rather, it’s the work of a writer deeply schooled in the essay. Whenever he caused trouble in the classroom as a child, Coates’s mother made him write out explanations of his behaviour. This ritual ‘of constant questioning, questioning as ritual, questioning as exploration rather than the search for certainty’, as Coates puts it, guides ‘The Case for Reparations’ in two ways. First, through its uncomfortable questions about US history and social policy; second, through the example of Coates himself as an African-American writer ‘living with a free mind’ without knowing ‘whether or not one can ever truly live in a free body’, as Jesse McCarthy writes in The Point. Coates follows the example of James Baldwin, one of the best American essayists of the twentieth century, in that he wants his writing, and most of all its exploratory enquiry, to serve as a reminder that the moment of fiercest despair can also lead to piercing clarity. As an old slave spiritual has it, ‘The very time I thought I was lost, my dungeon shook and my chains fell off.’

*

At its most vibrant, an essay is pragmatic, a particular mind at a certain time in the act of finding out what it thinks. An essayist’s desire to pursue a thought wherever it leads could seem impertinent or extravagant; yet that pursuit can also be liberating – the creation of a space in which thought may be pursued in ways that the culture cannot tame. Instead of providing assurances about the state of the world, an essay comes alive through curiosity or doubt. If an essay does have convictions, they are based on something other than correctness, as well as on the awareness that it exists in a world that very often has little patience for it. When we read a great essayist, we get to know her in part through her acts of self-discovery, how she comes to know herself by exploring the ways in which she remains unknown to herself and aspects of the world remain unknown to her. An essayist’s power lies as much in her conclusions as her ability to challenge them. Rather than asking to be vindicated, essays encourage us to think.