As the shock of war gives way to reflection, Ukrainian public discourse has turned to questions of the past, present and future: When did Russia’s war on Ukraine start? What is it doing to society? And how will it end?

The influential Czech-born editor Antonín Liehm was a pioneer of East-West intellectual exchange and an early advocate of the ‘European public sphere’. In 2009 he gave a memorable keynote at the 22nd European Meeting of cultural journals in Vilnius.

Antonín Liehm, the founder of Lettre internationale, passed away on Friday 4 December in his native Prague. He was 96.

Few people have done more to bridge the gap between Europe’s east and west, at least intellectually, than Antonín Liehm. When the first French edition of the European magazine Lettre internationale was published in 1984 – followed by the Italian Lettera Internazionale the year after, the Spanish Letra Internacional in 1986 and the German Lettre International in 1988 – western-European writers and scholars not only could but had to start engaging with intellectual life behind the Iron Curtain.

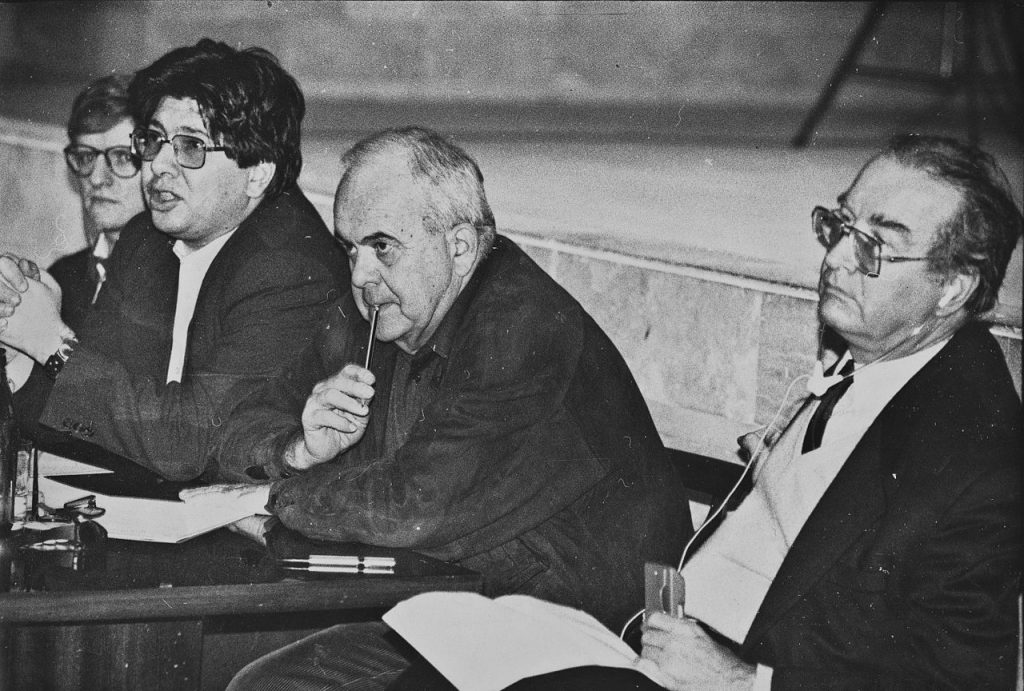

Antonin Liehm (centre) (l-r) André Lange, Kirill Razlogov, Liehm, Michel Ciment (Festival des films interdits, Moscow, January 1991). Source: Wikimedia Commons

The relationship between intellectuals in the east and in the west was ‘asymmetric’, as Frank Berberich, editor of the still-successful German Lettre, put it in a recent interview. One of the main motivations behind Antonín Liehm’s cross-border, multilingual and translation-centred initiative was to make that relationship more mutual.

The fact that this European publishing network did not survive the closing of the French mother journal only ten years later takes nothing away from the achievement. On the contrary, the publishing history of Lettre shows how cultural and intellectual endeavours are crucially dependent on more than just great ideas. Antonín Liehm knew that better than anyone.

He was only 21 years-old when he co-founded Kulturní politika in Czechoslovakia in 1945. At the beginning of the 1960s, he became the editor of Litérarní noviny. Under his reign, the former Stalinist publication of the Writers’ Association started publishing texts previously unthinkable under the communist regime. Circulation soared, reaching an incredible 130,000.

In those days he worked with Ludvík Vaculík, Milan Kundera, Pavel Kohout and Ivan Klíma. While many would describe Liehm as a seminal figure in the Prague Spring (a term that he might have been the first to apply to the political events of 1968), he always insisted that the dissidents of the 1970s and 1980s – Václav Havel and others – belonged to a different generation. They had their own journals, as he poignantly put it in a conversation with Roman Léandre Schmidt.

After the hopes of the Prague Spring had been dashed, Liehm left Prague for Paris. He taught film at universities there and in the US, before he could finally realize his plans of a new journal in 1984.

He was 60 when the first issue of Lettre internationale came out. Modelled on what he had done with Litérarní noviny 25 years earlier, there was nothing like it in western Europe. It brought together the divided continent marked by the Cold War: a common European forum for intellectual debate.

But it was just as hard to keep the project alive as it had been to raise the money to start it. In 1993, in a speech held in front of European bureaucrats and commission representatives in Brussels, Antonín Liehm declared that he was tired of running after people who though they could help financing his transnational endeavour, didn’t understand why they should. He was about to turn 70 when he announced that Lettre internationale would be cancelled.

Some 15 years later, in May 2009, I spent most of the 22nd European Meeting of Cultural Journals in the company of Tonda, as he was called among friends. Those spring days were pleasantly warm, but he was not in particularly good health, so we either very slowly walked the streets of Vilnius, or sitting in taxis, tried to bridge the short but still challenging distances between the conference venues.

On the way to the presidential palace, where he was to deliver the keynote, Antonín leaned over to me in the back seat of the taxi, whispering: ‘Never get old, Carl Henrik. It’s not worth it.’

It was clear that he meant what he said. And yet, when he addressed the Eurozine network from the rostrum in that impressive reception hall – in the presence of the host of the evening, the Lithuanian president Valdas Adamkus – the 85-year-old publishing legend managed to pep more energy into the audience than any of us could have. The challenge for a younger generation of cultural workers, he said, was to form an international body that united all fields of artistic activity, from music to theatre to publishing. ‘When that monster opens its mouth’, he said, ‘politicians will have to take note.’

And then he got concrete. ‘It is one thing to dream, to have ideas. We all have them,’ he declared. ‘But then comes the uninteresting work, the daily grind, which may not have much to do with big ideas and grand cultural, philosophical or social projects, but just organizing and getting people together who want to keep their ideas alive. This gruelling work may not be terribly interesting – we prefer to move in a field of dreams, ideas and art and beauty – but we must not neglect it.’

Antonín Liehm’s ‘daily grind’ speech became a constant reference for those of us involved in the journals network Eurozine at the time. A guiding principle. And the insight it communicates is no less valid today. If those paying court to the idea of a common European public sphere would walk their talk, and were prepared to put in at least some of that ‘gruelling work’, then Europe would be a very different place. At least intellectually.

Published 7 December 2020

Original in English

First published by Eurozine

© Carl Henrik Fredriksson / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTSubscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

As the shock of war gives way to reflection, Ukrainian public discourse has turned to questions of the past, present and future: When did Russia’s war on Ukraine start? What is it doing to society? And how will it end?

Jürgen Habermas recently argued that the pandemic measures of the German government hadn’t gone far enough. To weigh the state’s duty to protect life against other rights and freedoms was unconstitutional, he warned. In the ensuing controversy, critics accused him of authoritarianism. Were they right?