“I have something left in reserve”, Witold Gombrowicz (1904-1996) wrote in the “Introduction” to the first volume of his famous intellectual achievement, Diary – “but what remains is rather intimate, I would prefer not to present it here. I don’t want to cause myself trouble. Maybe someday […] Later.” Trouble? Gombrowicz had never seemed particularly averse to causing trouble for himself through his previous literary provocations: the revaluation of Polishness; exposing the lack of intellect among various hommes de lettres; ridiculing worshippers of form and enemies of individuality.

Today we know the source of Gombrowicz’s fears. That “something left in reserve”, closely guarded and carefully annotated by the author until his death, was recently published in Poland for the first time as Kronos. Gombrowicz’s private diary is a notebook, a chronicle, a dry record of the facts of Gombrowicz’s life. This is not a literary creation. Gombrowicz presents himself to us, as well as to himself, completely naked and performs a brutal auto-vivisection with surgical precision. We get to know about his illnesses (eczema, ulcers, syphilis, crumbling teeth, liver pains, sciatica, asthma), his casual hetero- and homosexual partners (as he noted in 1956, “Eroticism: great calming down, 11” – where “11” refers to the number of sexual partners that day), financial accounts (“I have about 16,000 dollars, oh the irony!”) or his own evaluation of his literary career (“Growing prestige in Poland and Germany”). Finally, we see him ageing and struggling with his own body.

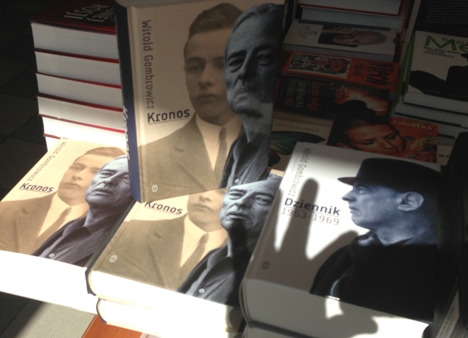

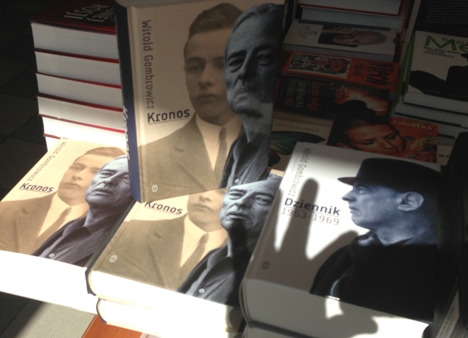

Piles of Witold Gombrowicz’s two diaries in a bookstore in Warsaw. Photo: CHeFred

The earlier Diary tells us how Gombrowicz perceived Kronos – 68 pages of not always clear handwriting. In his notes from 1963 we can read: “one of my suitcases in the cabin contains a file, that file contains many yellowed papers with a chronicle, month after month, of my own comings and goings. […] I ask, what to do with this litany of details?” And a few lines below, Gombrowicz continues to outline how Kronos was supposed to be an attempt to capture the past and confirm that his life was not merely a “raving of chaos”.

That’s Gombrowicz. But how are these notes to be read today, almost 44 years after the author’s death? What kind of a writer and what kind of a person do they present? Do they help renew our understanding of Gombrowicz’s works? In interview with Adam Puchejda, Jerzy Jarzebski, chief editor of Kronos, emphasizes Gombrowicz’s chronicle as a document in which he presents himself as a continuous debutant: “Reading Kronos, we find out what it means to start from scratch in the middle of one’s life.” It is also, in Gombrowicz’s words, an attempt to prove that ‘there is a Hand that shapes my life’.” Pawel Majewski points to the fact that the “provisory bookkeeping” is another of Gombrowicz’s masterpieces of “self-exposure”; indeed, the acute sense of his own corporality pervades Gombrowicz’s literature. “The deceased Gombrowicz”, Majewski writes “gave us a valuable tool. In these incoherent, clumsy notes, he provides an intimate – impossibly intimate – account of his life.”