A special issue of ‘Internazionale’ focuses on Italian emigration since the Risorgimento: including articles on how the Belgian, German and Brazilian press saw the new arrivals, their problems and achievements.

Belgium

The flow of Italian migrants to other European countries intensified after the Second World War. Italian institutions began to encourage departures by signing bilateral agreements such as that with Belgium in 1946. Italy sent around 50,000 workers to Belgian mines, receiving coal supplies in exchange.

But, according to Le Soir, reporting a few months after the agreement, Belgian managers ‘are not satisfied with the Italian miners, who for their part are not particularly happy with the working conditions’. Many workers only left Italy for want of alternatives and ‘their efficiency is usually much worse than that of prisoners of war’ who had worked in the same mines before them.

Ten years later, 262 miners – 137 of them Italians – died in a fire in the Bois-du-Cazier mine at Marcinelle. The date is one of the gloomiest in the history of Italian emigration. ‘Why do mine managers stubbornly refuse to give miners the right to check safety measures?’ asked Belgium’s Communist Party newspaper Le Drapeau Rouge in the aftermath of the tragedy.

Brazil

Between 1861 and the beginning of the Great War, 1.5 million Italians went to Brazil to almost exclusively work as farmers. Living conditions were often very hard, but in 1925 A Federação, a daily newspaper of the Republican Party of Rio Grande do Sul, applauded Brazil’s ‘unmatched hospitality’ towards Italian and other migrants. ‘The colonists are satisfied. Migrants cultivate the land they own and build with their own hands a wealth they never would have achieved in their home countries.’

Every year on 21 February, Brazil celebrates the national day of the Italian migrant, which it has done since 2008. In 2020 Folha de Valinhos, a local newspaper from the state of São Paulo, recalled the sacrifices that Italian migrants once made and the changes they brought to the region’s agriculture and economy. For example, in 1901 Italian immigrant Lino Busatto introduced the fig to Valinhos, which is now recognized as a typical fruit of the area.

Germany

Of the 5.3 million Italians registered abroad in 2019, more than 760,000 live in Germany. In the 1950s and 1960s, Gastarbeiter were mostly Italians. In 1964 Der Spiegel wrote that ‘without the Gastarbeiter’s contribution, the economic success of West Germany would not have been possible’ but that most ‘feel more like inhabitants of a ghetto than guests’.

Some of that feeling persists several decades later. In 2008 Die Zeit asked why, of all schoolchildren with migrant backgrounds, Italians struggled the most at school. ‘The educational failure of young Italians is paradoxical and disproves some of the more simplistic theories about the causes of low educational attainment.’ Why do Italians struggle more than the children of Turkish immigrants, even though they are not subject to the same prejudices?

Many Italian children not only have difficulties with the German language but also are often only versed in the Italian dialect spoken at home. However, the main fault lies with the ‘selective character of the German school system,’ in which academic success depends on family background more than in any other industrialized country.

This article is part of the 4/2021 Eurozine review. Click here to subscribe to our weekly newsletter to get updates on reviews and our latest publishing.

Published 3 March 2021

Original in English

First published by Eurozine

© Eurozine

PDF/PRINTNewsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Related Articles

The privilege of anxiety

On censorship, self-censorship and Palestine

A conversation with Palestinian–German scholar Anna-Esther Younes about the mechanisms of anti-Palestinian repression in Germany, Europe and beyond; about intergenerational knowledge transfer amidst an increasingly isolating political climate; and about fostering solidarity between struggles.

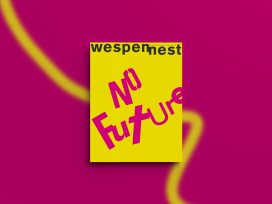

No future!

Wespennest 186 (2024)

Historicizing Doomsday: how West German ’80s pop marketed angst; why the next generation doesn’t want to live fast and die young; whether we’ve really reached tipping point; an what ‘no future’ meant for early Christians.