The protests over the arrest of Istanbul mayor Ekrem İmamoğlu are the biggest display of anti-government feeling in Turkey since Gezi Park. Again, people are challenging the culture of public silence; and again, they are being punished for doing so.

Critical assessments of a century of Turkish republicanism: why a utopian revival would do the country good; what official history does not say about feminism; how the republic lost supporters left and right; and why the media have rarely been independent, as Atatürk intended.

On 29 October 1923, an assembly in Ankara proclaimed the formation of the Republic of Turkey and elected Mustafa Kemal Atatürk as its first president. The new Republic promised a fresh start after more than a century of conflict that had seen the Ottoman Empire contract and collapse.

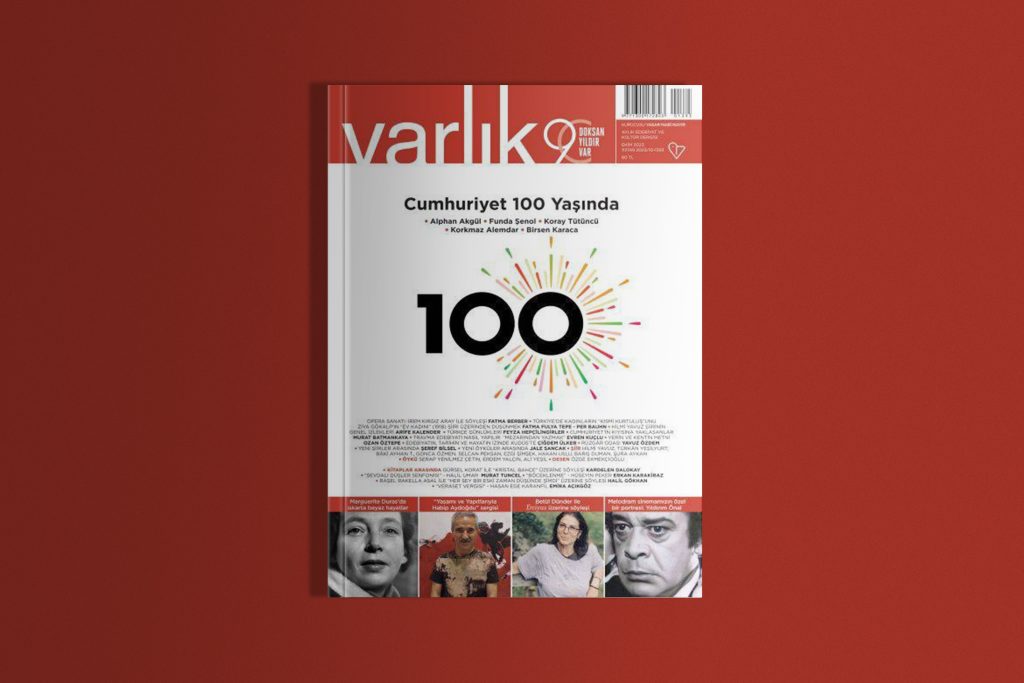

Varlık marks the national centenary with a collection of articles on the achievements and failings of the Kemalist Republic, a radical project of sweeping reforms to laws, language and education aimed at building a modern, secular and independent nation.

Alphan Akgül reflects on Turkey’s 20th-century experience of dystopia and utopia, from the horrors and destruction of World War I and the subsequent War of Independence to the utopian thinking that powered the early years of Atatürk’s Republic.

Looking at present-day Turkey under Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and the AKP, Akgül is convinced that a new wave of utopian thinking is needed. He suggests combining modern thought with the inspirations of a century ago:

Developing a new economic and ethical model by reconciling [Thomas] Piketty’s utopia of libertarian socialism with the idea of solidarity in the first years of the Republic can enable our Republic to rise from the ashes.

Turkey’s official history claims that the struggle for women’s rights was born alongside the Republic. The narrative according to which the founding fathers ‘granted’ rights to women has been a weight on women’s backs ever since, retarding examination of the ‘brave and loud’ movements during the Ottoman Empire, argues Funda Şenol.

Starting from those feminist forerunners, she traces a century of women’s magazines and movements that were sometimes aided by the state, and sometimes hampered by it. The Turkey of today, writes Şenol, is one in which the ‘authoritarianism of the AKP, which began with the Gezi protests and deepened with the 2015 election, has led to a regression in the struggle for gender equality’.

Koray Tütüncü starts his examination of the Republic with an account of how he went to university ‘having internalized without the slightest doubt the Republic’s historical narrative, worldview, and vision for the future’ but then found his certainties crumbling. The Kemalist position was attacked from the left as an elitist project and from the right as a betrayal of deep cultural values.

‘For both, the basic problem was that the Republic was unable to integrate with society. In reproducing its own values, the Republic could not establish a democratic relationship. And because it could not, neither could it meet its promises of general welfare and happiness. Because it spent all its energy in conflict with its own public.’

Korkmaz Alemdar traces the successes and failings of the media system established by the Republic in the 1930s. The original Kemalist vision was of trained, educated journalists working for autonomous media organizations under the protection of strong labour laws. While some of those elements existed at times, the demands of politics, international relations and business steadily eroded and undermined them in various ways.

Still, says Alemdar, there are lessons to be learned a century later about the ‘importance of autonomous media institutions and what it means for journalism to be strong in the face of power and capital’.

Also to look out for: In a series of interviews carried out over the years with individuals of different generations, Birsen Karaca offers personal histories of how the Republic changed lives through educational reforms.

Published 11 October 2023

Original in English

First published by Eurozine

Contributed by Varlık © Eurozine

PDF/PRINTSubscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

The protests over the arrest of Istanbul mayor Ekrem İmamoğlu are the biggest display of anti-government feeling in Turkey since Gezi Park. Again, people are challenging the culture of public silence; and again, they are being punished for doing so.

State control of the Turkish media is exercised through subordinate and heavily concentrated ownership structures. With barely room left for independent outlets, digital platforms have become a means for journalists in Turkey to continue to provide reliable information.