The ‘Russian World’ in Germany

Pro-Kremlin propaganda spread through social media is causing a shift to the far-Right among Germany’s native Russian population. Nikolai Mitrokhin considers the implications for German politics in advance of the September elections.

On 16 May 2017, the Ukrainian president Petro Poroshenko introduced sanctions against a large number of Russian individuals and legal entities, most prominently the major Russian social networks, search engines, email providers and antivirus software.1 The decision was not well justified to the public and elicited a firestorm of criticism both in Ukraine and abroad. The next day, German chancellor Angela Merkel held a closed meeting with representatives of the Russian-language community in Germany. It was the first of its kind in the entire history of the contemporary German state.2 Three days before, the Russian service of Deutsche Welle began a series called ‘Political Talk Show Quadriga’, dedicated to the upcoming German elections. In its own words, it ‘offered Russian-speaking German politicians a platform for discussion’.3 Deutsche Welle – which is intended for broadcast abroad – thereby overstepped its mandate, effectively inserting itself into domestic political battles.

These three events in two very different countries arise from a common factor: the major role that Russia has come to play in the domestic European politics through Russian-language social networks and media outlets. This article is an attempt to describe the situation through the lens of one notorious example – the recent ‘case of Lisa F.’

Russian native speakers in Germany

There are no official statistics concerning the number of Russian native speakers living in Germany. Different criteria have been used to produce estimates and a microcensus conducted in 2014 suggests that no less than three million people migrated from the former USSR to Germany. This would constitute almost four per cent of Germany’s population. Irrespective of the exact number, Russian speakers form the next largest linguistic group after the country’s native German-speaking population.

The Russian-speaking population can be broken down into a number of subcategories. These include Russian Jews, who arrived principally in the 1990s; economic migrants from the former USSR, a significant proportion of whom are citizens of the EU (people arrived from the Baltic States for example, as well as Ukrainians and Moldovans with Romanian passports); women who have married ‘real Germans’; Chechens and political activists seeking political asylum in Germany; and undergraduate or postgraduate students enrolled at German universities. But the main sub-group are so-called ‘Russian Germans’, along with their family members who may belong to other ethnic groups, all formerly resident in the Soviet Union. According to official figures, they comprise no less than 1.4 million people.

In the USSR, between the 1940s and the early 1970s, Russian Germans were discriminated against. From the second half of the 1950s, their development was curtailed in semi-official ways. The group included a large percentage of rural people or first-generation city dwellers, with a high level of religious commitment and an above-average birth rate. The authorities discriminated against them and ordinary Soviet people would routinely accuse them of being ‘fascists’. Consequently, Russian Germans tended to function within closed family circles. Because of its size, the ‘extended German family’ came to be viewed as a recognizable phenomenon. It encompassed not only immediate relatives but may also have incorporated a number of groups linked by ties of kinship. These might form a sizeable community of several hundred people and include members of other ethnic groups.4

Once the families had moved to Germany, it became quite common for members to gather in a single town and settle there. In large cities this led to the formation of so-called ‘Russian areas’. Statistically speaking, in the provinces, the distribution of native speakers of Russian was less uniform. This might depend on whether there was a refugee centre in the area, or on the type of industry there. Whatever the case, today many small towns in the German provinces have a significant proportion of Russian native speakers, which makes the community a social and political force to be reckoned with.

It is significant that Russian speakers, and the ‘extended families’ of Russian Germans in particular, maintain permanent, horizontal bonds with other families and territorially based communities throughout Germany. Weddings, funerals, christenings or anniversaries of ‘Russian Germans’ can bring together dozens or even hundreds of people. This creates an active network of further contacts as well as offering possibilities for exchange and coordination independent of the communication methods generally recognized by external analysts, such as television or the social media.

Furthermore, unlike people of Muslim origin living in Germany, ‘Russian Germans’ who arrived in the 2000s are perceived as a group that has integrated well. Many second-generation Russian migrants (and a substantial number of people from the first-generation) are indeed successfully assimilated. Admittedly, there were some serious problems to start with, including a high level of crime among young males and the fact that the overwhelming majority of migrants had no knowledge of the German language. But this is now a thing of the past. Most people have since acquired some knowledge of German and found jobs. Levels of unemployment among this group are equal to those within the country as a whole. Their children – unlike those of many other migrant groups – aspire to enter higher education and, appear to be numerically outstripping ‘native’ Germans as they do so.

Russian German families tend to have children early on in life compared to ‘native Germans’ and to have teenage children by the time they reach an age of between 35 and 40. As second or third generation migrants, these children frequently do not speak Russian and have interests and views that differ considerably from those of their parents.

‘The case of Lisa F.’

Where do supporters of Vladimir Putin – those who uphold the notion of a ‘Russian world’ and back aggression in Ukraine – fit into the picture? In formal terms, their role is insignificant. The overwhelming majority of Russian Germans, and other Russian-speaking migrants, are not involved in Russian-speaking political or social organizations.

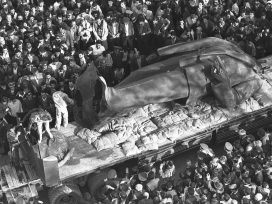

Yet the political potential of this group became evident on 24 January 2016, after Russian state television’s Channel 1 reported the alleged rape in Berlin of a ‘13-year-old girl called Lisa’, who was described as ‘Russian’. The perpetrators were said to be recently arrived migrants of Arab origin. Following this news, demonstrations against Angela Merkel’s migration policy took place in at least 43 towns in Germany. All of these demonstrations had the same official slogan: ‘We are against violence.’ In some cases, thousands of people came out onto the streets. At a number of these meetings, the idea of creating volunteer patrols was discussed, redolent of the early phase in the formation of the Donetsk and Luhansk ‘Peoples’ Republics’.

Despite the German authorities’ swift investigation of Lisa’s account, and the revelation that she had lied, the story significantly affected the political sympathies of Russian speakers in general, and ‘Russian Germans’ in particular, turning them towards the right-wing party Alternative for Germany (AfD).

In the autumn 2016 regional elections, the AfD won a significant proportion of votes in three German states, making for substantial gains in representation at regional parliaments for the first time. The Russo-German journalist Nikolai Klimenyuk wrote on his Facebook page that ‘in BW [Baden-Wurttemberg], areas where there are concentrations of people of Russian origin brought in spectacular results for the AfD: 43 per cent in the “Russian” area of Pforzheim, Haidach, for example, and 51.8 per cent in the “Russian” area of Wartberg, in the town of Wertheim. It is worth noting, however, that not only “Russian Germans” live there.’5

How could a previously politically inactive group have managed to organize these demonstrations so quickly? What mobilized it? Who leads ‘pro-Putin’ Russian speakers in Germany and how? Could something similar happen again in the 2017 elections?

Russian television

The most widely accepted explanation is the propaganda campaign run on Russian television. There can be no doubt that a significant proportion of Russian-speaking German citizens prefer to watch Russian television. Yet why is it that people who have lived in Germany for twenty years or more prefer Russian to German television? After all, for the most part they speak German well and appear to be almost completely integrated.

There is a moral or ethical reason for this. Many native Russian speakers do not trust news broadcasting on socio-political topics in German, nor do they favour it over the Russian equivalent. When drawing comparisons between Russian and German television, they generally remark on a lack of dynamism in German TV news presentation, the sparse list of topics covered and dated video footage. To this day, some leading news programmes retain a style reminiscent of Soviet state television’s news programme ‘Vremya’, from around 1985. But that is not all.

Modern journalism aspires to the status of the ‘fourth estate’, but the profession has fallen between two stools. On the one hand it aspires to search out and express objective public needs (to ‘reflect the interests of society’); on the other it finds itself mirroring the urge of a highly educated elite to promote liberal left values and, in effect, ‘educate the masses’. The latter is especially the case in Germany for historical reasons. German public service television is profoundly ideological (though some may argue that it propagates values rather than ideology). People who can recall the Soviet experience are highly sensitive to this. The basic premise behind German public service broadcasting – that Germany as a nation was responsible for the disaster of World War II – is lost on migrants form the former USSR. They see themselves as victims of the war, not as the guilty party. This is true of Russian Germans, Jews and other economic migrants with a Slavic or Baltic background.

Their scepticism towards German official media is aggravated by the fact that, in news stories, some issues are highlighted while others remain hidden. The clearest illustration of this would be the events in Cologne on New Year’s Eve in 2015, where police did nothing to prevent groups of male migrants sexually harassing and attacking women and, in collusion with the press, covered up the facts for some time.

Obviously, the system that underpins the state media in Germany bears no comparison with the scale of Russian state propaganda. But such cases – though often exaggerated – offer an opportunity for critics of the German political system (on the left and right) and for supporters of Putin’s Russia to promote themselves as unmaskers of ‘fake news’, including the lies of the German authorities and the influence of global financial capital, which allegedly dictates the media agenda.

It is equally important that native Russian speakers find it easier to understand news broadcasts in Russian, despite their relatively high level of German language competence. That is why, after a hard day’s work, many Russian speakers will switch on Russian TV (discs with programme packages can be bought in the many Russian supermarkets in Germany). Alternatively, they may sit down to talk on Russian social networks.

Although German TV channels recognize the presence of other linguistic minorities in the country, particularly Turkish speakers, they almost entirely ignore Russophones. There are no Russians moderators or lead actors in serials, and they seldom participate in talk shows – where the presence of participants with Turkish or Muslim background seems obligatory. No documentaries are made about the problems and achievements of Russian speakers. In 2015, I came across an issue of Stern devoted to Russian–German relations. One headline read ‘They are over here!’ The article described the life of a typical ‘Russian-German’ family, the very existence of which was evidently a source of wonder.

There are two fundamental reasons why discontent has developed among native Russian speakers in Germany: distrust of media attitudes and a need to find solace in the Russian linguistic context outside work. But this is not a sufficient explanation for their political mobolization.

Russian social networks

Germany has two significant categories of pro-Putin supporters among Russian speakers. First, organizations supported by the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Embassy (especially state branches of the Congress of Russian Compatriots; the Russian cultural organizations linked to them; and some Russian Orthodox Church parishes). Second, grassroots activists often not associated with any organization, or else connected with very marginal groups.

The first category greatly values their social and legal status, and frequently receive funding from local authorities in Germany. Some of their activists genuinely oppose Putin – though these may be few in number. Because of their position, they prefer to avoid open political involvement and instead, like the proverbial calf, try to milk both sides. The defining moment comes when they are obliged to choose whether or not to participate in the 9 May celebrations in Germany. The mobilisation of the second group increased following the annexation of Crimea. Social networks have played a key role. Like the Soviet newspaper Pravda a century ago, social media today are central to propaganda, recruitment and organization.

Users of Russian content in social media generally go to networks such as Odnoklassniki (‘Classmates’) and Vkontakte (‘InContact’).6 These services are geared towards people who do not want to write their own material (some have no higher education); rather, their policy is to create a circle of users and draw them into the Russian-speaking context. In both networks, content devised exclusively for users is reposted by those users. On the whole, this content consists of ‘demotivators’ (pictures or photographs with a brief caption) or ‘pithy’, often anonymous, dictums and short anecdotes.

A significant proportion of demotivators have an overt or underlying ideological message. In the first instance, they play up topics such as Russian food and drink (a form of patriotic ‘food porn’); nostalgia for the USSR; the uniqueness of everything Russian; the greatness of Russian history or the importance of Russia’s victory in World War II; patriotism; the power of the Russian army or of Russians generally; Putin; and the inanity, ugliness or unacceptability of anything foreign (this is likely to involve blatant racism, antisemitism and homophobia). Overall, demotivators serve to affirm identity and define ‘us’ or ‘our fellow-countrymen’ in the face of constant attacks by ‘jackasses’ from Ukraine, ‘Gayropa’ and the USA.7

Thousands of demotivators of this kind are produced on what is clearly a professional basis. Presumably this is done in ‘troll factories’ functioning within the framework of the ‘partnership between private and state enterprise’ that characterizes Putin’s Russia. At a press conference on 22 February 2017, Russian defence minister Sergei Shoygu mentioned the great importance of ‘information operations troops’, which were proving far more effective than the former department of counter-propaganda at the General Staff that existed in the late Soviet era. Although representatives of the State Duma later explained that the minister was merely referring to defending Russian computer systems from external attack, it sounded like a full acknowledgement of the fact that an ideological war was being waged. There can be no doubt that this campaign was intended abvove all to affect social networks.

The people who create demotivators encourage users to form communities. One way of doing this is to introduce a form of coercion. For example, the most popular button on a demotivator on Odnoklassniki is Zhmi Klass (‘Press great’) – the equivalent of ‘Like’ on Facebook. This is an effective sociological tool. It offers users the opportunity to join groups that share their interests. When researching this article, the list of groups recommended to my account was as follows: ‘Slavyane’ [Slavs] (146,000 members); ‘Forum for supporters of Vladimir Putin’ (161,000 members); ‘Political review: We are for Putin!’ (647,000 members); ‘Dnieper – arise!’ (32,000 members).

The Odnoklassniki network offers communities for former servicemen such as ‘People you served with in the army’, ‘Veterans of the armed forces of the USSR’ and ‘Officers of Russia’, not to mention hundreds of themed groups for regimental colleagues or fellow students of military academies. Odnoklassniki and VKontakte networks also organize numerous themed groups for Russians living in Germany. Some reflect ideological preferences (Russian Germans for Alternative for Germany – 5500 members) or pro-Russian and pro-Putin loyalties and combine German and Russian flags on their banner, sometimes with an image of the Russian president. Some are Germany-wide – for example on Odnoklassniki there are groups called ‘We live in Germany: News and politics’ (34,000 members), ‘Russian Germany’ (45,700 members), ‘Voice of Germany’ (23,000 members) ‘Russians in Germany’ (20,700 members), and on ‘VKontakte’, ‘Russians in Germany UNITE!’ (5900 members). However, regional groups are considerably more numerous. They may be formed with reference to a current place of residence in Germany or to the commemoration of migration from a particular city, village or kolkhoz in Russia or Central Asia. The closed group ‘Novodolinka Ermentausky region’, run by a woman living in Germany, has almost 2000 members,8 while a competing group called ‘Pavlovka, Novodolinka, Tselinogradskaya region’ administered by another woman resident in Germany has almost 3000.9 But, as will be shown below, some communities may be set up and run by people based outside the borders of Germany.

From social networks to political activism

This is where small political groupings or German-based branches of Russian organisations come into play. They aspire to translate long-distance support into concrete action. The most prominent of these are the ‘National-liberation movement (NOD) – Germany’, ‘Einheit’ (Unity), ‘Nochnye volki’ (Night Wolves) and the projects of the former professor Rainer Rothfuss.

Their activists create and support groups in social networks (often working anonymously). This is a cheap way of coordinating political action and offers mass outreach. The first large-scale display of genuine political activism was the ‘Help the Donbas’ project. This involved the collection of goods, food and medication to help the population in areas of eastern Ukraine under the control of pro-Russian fighters and sending supplies to Donbas. It is quite likely that the network also dispatched people who wanted to participate in the fighting there. According to reports by German journalists published early in 2015 that made reference to information supplied by the security services, about a hundred German residents travelled to fight in Donbas. Some had been killed in the war by the time the reports appeared.

‘Humanitarian aid’ of this kind can be a framework for further politicization. This happens under slogans that, activists believe, counter the aggressive intentions of the United States and NATO. For example, is only a small step from the group ‘Peace for Russia and Germany’ to public protest. The trigger for action is the imminent danger that supposedly threatens us all.

The reason for the deployment of ‘Russian Germans’ was Merkel’s decision to allow hundreds of thousands of refugees from the Near and Middle East to enter Germany. In many ways, ‘Russian speakers’ brought their racist cast of mind to Germany when they moved to the country. Once there, they had to compete with other migrant groups and their prejudices have not weakened. The incident in Cologne confirmed and sharply increased fears of an approaching and unavoidable danger.

German rightwing radicals and neo-Nazis were the first to exploit the mood that the Kremlin had done much to inflame. The Right have long seen ‘Russian Germans’ as potential allies and, since the 2000s, have worked hard to draw them into their ranks.10 But because right-wing radicals had a negative image in Germany at the time, their efforts to join the political mainstream and attract voters proved fruitless. Even conservatives did not respond.

The refugee crisis of 2014 and 2015 caused this situation to change, with the populist backlash against uncontrolled migration and Islamic organizations inside the EU. Neo-Nazis were able to infiltrate the ranks of these movements by applying Trotsky’s theory of ‘entryism’. Small, organized forces entered the leadership of broad social coalitions and steered them towards revolutionary goals that the majority of the group had never promoted themselves. The AfD originally had a very diffuse ideology that combined elements of both liberal and far-right conservatism. But the fact that the German political establishment rejected the party and that neo-Nazis became active in the movement transformed it into a glaringly anti-immigrant group.

Traditionally, Russian Germans were not only supporters of the Christian Democratic Union (and its counterpart in Bavaria, the Christian Social Union) but of the most conservative wing within the party. Over the past five years, Merkel’s overt shift of policy to the left has disappointed them. Her decision to allow entry to refugees from Syria proved to be the ‘last straw’. After that, Russian-speaking political activists, with a visible presence on social networks, refused to support her. At present, I am not aware of a single German Russian-speaking social media group that backs Merkel. Instead, in autumn 2015, ‘Russian German’ groups on Russian social networks were awash with advertising for the AfD and with material that attacked the chancellor personally.

The established parties – especially the CDU and the Social Democrats (SPD) – may have lost the social media battle for the Russian-speaking voter. Indeed, it might be more accurate to say that they never entered the battle in the first place. The Christian Democrats have just one group on Odnoklassniki – a branch of the party based in a small provincial town. A more organized webpage – ‘Russian-speaking Social Democrats in Germany’ – has just 39 subscribers and consists entirely of information published by a single author.11 In contrast, there are four groups created by supporters of AfD, with 10,000 members overall.

It is widely known that far-right radicals have been actively collaborating with the Kremlin since the early 2010s. This cooperation culminated in the ‘the case of Lisa F.’ Even while the German police were still investigating the incident, demonstrations took place in dozens of towns, all with similar slogans and the same symbol (yellow balloons with black stickers) denouncing the ‘lies of the press’. This degree of organization would have been impossible without systematic co-ordination. It makes sense to suspect that neo-Nazi structures on the Internet, or the AfD itself (and to a certain extent ‘Einheit’), might have been involved. Almost all of those who spoke at or participated in the demonstrations were native Russian speakers. But far-right Germans also addressed some of the meetings. They were easily identifiable by their appearance, the manner of their performance and the slogans they used.

The technology of organizing protest

The Lisa F. campaign was interesting not only in terms of how the demonstrations were organized, but because of the innovative way in which people were summoned to attend. No information appeared in advance in public, yet people still assembled. The semi-literate but vigorous call to attend the demonstrations appeared in Russian. It was disseminated on social networks and read:

ATTENTION! THIS IS WAR!

A 13-year-old girl has been raped in Berlin. The corrupt authorities and their faithful dogs, the police, are trying to cover up the facts as best they can. The press has been silent for a full week.

ON 24.01.2016 FROM 14.00 TO 16.00, WE THE ENTIRE RUSSIAN-SPEAKING POPULATION, GREAT AND SMALL, WILL MARCH ONTO THE MAIN SQUARES OR TO THE TOWN HALLS OF ALL POPULATED AREAS IN GERMANY, TOGETHER, AT THE SAME TIME.

ANYONE WHO IGNORES THIS CALL WILL HAVE THIS RAPE ON THEIR CONSCIENCE. THIS IS THE FIRST PEACEFUL WARNING PROTEST TO THE AUTHORITIES.

We are the last bastion. If we do not unify and save Germany we shall be suffocated, like rats in our own holes. Repost this. Put it in your notebook (SHARE). Everyone must know within a week.

I accessed this text through personal contacts. It had been disseminated in a new way – by personal invitation through social networking sites not indexed in search engines (primarily Odnoklassniki and Facebook), through messaging services (mostly WhatsApp) and no doubt through closed groups on Vkontakte. The text was not made freely accessible on open online communities popular among Russian Germans. Residents of Germany who had made clear their opposition to Putin or their loyalty to the German authorities did not receive it. The call to attend the demonstrations was sent out either using a contact list or through relatives, friends, acquaintances and colleagues of a similar political persuasion.

Prospects for the elections in September 2017

The success of the German police in establishing the circumstances of Lisa’s ‘rape’ pacified feelings somewhat, but left the political views of many Russian-speaking residents of Germany unchanged. It has become clear in recent years that the Russian authorities are seeking to manipulate Russian speakers in Germany in their attempts to achieve a tactical goal: to ‘punish’ Angela Merkel personally, and the German leadership in general, for their tough stance on Ukraine. In addition, Moscow is seeking strategically to destabilize Germany’s ties with NATO and the USA, particularly through the revival of ethno-nationalism and racism.

At the same time, the Russian authorities have no desire to be caught red-handed. If Russian-speaking German activists are not always as careful as they should be about posting on social networks, then it is a matter of concern to Moscow. In the winter of 2016–2017, the Odnoklassniki network unexpectedly announced that secret groups could now be created within the network. Information about them would not be available to outsiders. Not long afterwards, VKontakte informed its users that ‘in response to numerous requests’, photographs would be closed to public viewing. In the past, VKontakte had offered plenty of scope for copying and sharing photographs and other material.

What does all this mean? Has the Russian-speaking population of Germany slipped out of control, as far as the German authorities are concerned? Has the group changed its political preferences and rejected traditional parties? Many experts in the German media believe that Putin has not succeeded in using ‘Russian Germans’ effectively. Support for anti-migrant and anti-Merkel slogans turned out to be less enthusiastic than was predicted. According to Ingo Mannteufel, the head of the Russian Service of Deutsche Welle, about 50,000 people turned out to demonstrate in support of Lisa – certainly a minority among Germany’s Russian speakers.

Moreover, if one looks at the figures in areas where AfD has been successful, it becomes clear that it received most votes in eastern areas of Germany where there are few Russian speakers. Statistics concerning social networks also indicate that Russian speakers are more interested in joining non-political online communities. Politicized groups have relatively limited audiences. Given that Russian-speaking residents of Germany with pro-Russian sympathies are involved in some of the most popular online communities, one can assume that the total number of ‘pro-Putin’ activists in the country comes to between 50,000 and 60,000. This estimate roughly equals the number of people who participated in the demonstrations, though of course not everyone would have been able to attend.

At the same time, the number is relatively high. The problem is not only that these actively ‘pro-Russian’ citizens are lost for mainstream political parties. It would be fair to say that this group is the tip of the iceberg. People holding an actively pro-Putin position dominate online communities of Russian speakers in Germany, and represent what is the largest contingent within this environment. This does not mean that all Russian-speaking Germans are under their influence. Many do not read or watch Russian-language media or use social networks. Those who do may well have their own political position. Equally, it is impossible to gauge the electoral influence of this group at the present time. We will have to await the results of state and federal elections. However, a group as large and active as this is bound to affect the behaviour of the entire Russian-speaking community in Germany, especially when crisis situations arise.

An earlier version of this article was presented at the conference “Russian-speaking Communities 2016 in a Fragmented Media Environment” (Helsinki, 13.10.2016). The author is grateful to the Slavic-Eurasian Research Center at Hokkaido University (Japan) for the opportunity to work on this article.

http://korrespondent.net/ukraine/3851116-poroshenko-zapretyl-vkontakte-y-odnoklassnyky

http://p.dw.com/p/2dABH

http://p.dw.com/p/2d4Ou

Nikolai Mitrokhin, Erika Rondo, ‘Nesostoiavshaiasia avtonomiia: nemetskoe naselenie v SSSR v 1960-1980-kh godakh i ‘vosstanovlenie respubliki nemtsev Povolzh’ia’’ [Autonomy thwarted: The USSR German population in the 1960s-1980s and the ‘reestablishment of the Volga German Republic’’, Neprikosnovennyi zapas, 4(78)/2011. Mitrokhin N. and Rondo E., Failed autonomy: the German population in the USSR 1960s-1980s and ‘the reestablishment of the Volga German [Autonomous Soviet Socialist ]Republic’// Neprikosnovennyi zapas, Moscow 2011, No. 4 (78), http://www.nlobooks.ru/rus/nz-online/619/2454/2528/

Nikolai Klimenyuk’s Facebook page, 15 March 2016.

On Facebook, a similar role is played by ‘the oldest and largest Russian-German satirical community, ‘Der Russen Treff’’. The community was created 1 January 2010 and now has 137,800 Likes.

See for example the ‘Russkaya Germaniya’ group on Odnoklassniki, https://ok.ru/group/51705122783309/video/g51705122783309; cf. too Oleg Riabov and Tatiana Riabova, ‘The decline of Gayropa? How Russia intends to save the world’, Eurozine, 5 February 2014, http://www.eurozine.com/the-decline-of-gayropa/

https://ok.ru/novodolinka

https://ok.ru/group/47194893713441

Tatiana Golova, ‘Akteure der (extremen) Rechten als Sprecher der Russlanddeutschen? Eine explorative Analyse’, in: Markus Kaiser and Sabine Ipsen-Peitzmeier (eds.), Zuhause Fremd: Russlanddeutsche in Russland und Deutschland, transcript, 2006, 241–274.

https://ok.ru/group51652225728714

Published 6 June 2017

Original in Russian

Translated by

Irena Maryniak

First published by Eurozine (English version)

© Nikolai Mitrokhin / IWM / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTIn collaboration with

In focal points

Newsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Related Articles

Russia’s orbit

Osteuropa 4/2024

Repression, murder, war: on the logic driving the Putin regime toward ever-greater excesses of violence. Featuring Yuri Andrukhovych on the Russian colonial empire – the only ever to have tried to reconquer a former possession. Also: articles on Navalny, and on what next for Georgia?

Turkey is no longer a dissident safe haven. High-profile cases of outspoken exiles kidnapped or even killed by spies when in the country attest to the risks. Interviews with Iranian and Russian exiles reveal deteriorating circumstances, from visa refusal to societal racism, police persecution and serious abduction threats, exposing uncertain, shifting political ground.